Considerable Excitement and Heavy Betting: Origins of Base Ball in the Dakota Territory

This article was written by Terry Bohn

This article was published in Spring 2020 Baseball Research Journal

When the Yankton Treaty was signed in 1858, the United States government acquired a large parcel of land: the northernmost part of the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, much of which had been Sioux Indian land. In 1861, the area was incorporated as the Dakota Territory. Its borders changed over the next decade, at one time including parts of present day Montana and Wyoming, but eventually shrank to what is now North and South Dakota. The first territorial capital was established in Yankton (the far southeast corner), but was later moved to Bismarck (now North Dakota) in 1883. In 1889 the territory was split in half at the 46th parallel when President Benjamin Harrison signed legislation making North and South Dakota the 39th and 40th states in the Union.

White settlers in the territory followed the transportation routes: first rivers via steamboat, then wagon trails, and later the railroads. Two of the earliest communities were Yankton and Vermillion, both located on the Missouri River in the southeast corner of the territory. The Yankton band of the Dakota (Sioux), for which the city is named, occupied the site of the city when Lewis and Clark stopped there in 1804. Yankton was incorporated as a city in 1869 and became an important steamboat stop, especially after gold was discovered in the Black Hills a few years later. French fur traders first visited the city of Vermillion in the eighteenth century and named it after a red pigment made from the mineral cinnabar that local Indians used as paint. The Dakota name for the town translates to “The place where vermillion is obtained.” Vermillion sits east of Yankton, was founded in 1859 and incorporated in 1877.

The author has previously established that the earliest recorded base ball game in Bismarck occurred in 1873.1 Other historians have documented that soldiers in the Seventh Cavalry at the US Army post at Fort Abraham Lincoln formed the Benteen Base Ball and Gymnastics Club around the same time.2 Within a short time a second club had been formed, and the two nines played base ball while on the Black Hills Expedition in 1874. Four members of the post’s base ball teams suffered gunshot wounds at the Little Big Horn in 1876 and one ballplayer died with Custer in the battle. But the Benteens were not the first base ball club in the Dakota Territory. This essay traces the first known base ball clubs and match games in the southern part of the Dakota Territory through the decade of the 1870s.

|

The White Caps went to bat and made 23 runs in the first inning, enough to discourage any club, but the Coyotes went to the bat not one bit discouraged. They scored 12 runs. At the end of the 3rd innings, the Coyotes stood 40, the White Caps 30. —Yankton Press and Dakotaian, October 27, 1870 |

In 1869, the first fully professional base ball team was formed in Cincinnati, Ohio. The “Red Stockings” traveled across the country on the new transcontinental railroad and rang up a perfect record of 64 wins and no losses.3 That spring, the April 3, 1869, issue of the Dakota Republican of Vermillion, Dakota Territory, reported that the Star of the West Base Ball Club, probably named for a saloon of the same name in the city, was reorganizing for practice for the coming season. The term “reorganizing” implied that there may have been an earlier version of the club, but this is the first known written record of a base ball club in the territory. A match game between the Star of the West and the Excelsiors of Bloomingdale was scheduled for September 1 of that year, but no record of the result of the contest could be found.

The following year, several clubs organized in the area. When they organized in March 1870, the Coyote Base Ball Club of Yankton boasted of having, “…material enough to make a nine that can scoop anything this side of the Mississippi.”4 The Frontier Base Ball Club organized in Vermillion that summer and later changed their name to the “Spotted Tails.” An estimated 2,500 people gathered on July 4 in Vermillion as the Spotted Tails beat the “Shoo Flys” of Star Prairie, 36–6, in five innings. The first nine of the Young Americans squared off against the Lincoln Clippers at the Independence Day celebration in Lincoln, and the White Caps of Sioux City, Iowa, defeated the “Railroad” club of Cherokee, 76–41, at another July 4 event in the area.

Organizational structure of these clubs was similar to those formed in other parts of the country. The Spotted Tails published a list of the members, elected a slate of officers, adopted a Constitution and By-Laws, and formed committees on Finance and Grounds. At an August meeting of the Spotted Tails club, the following rules were adopted:

- The first nine shall meet every Saturday at two P. M. on the grounds and play a practice game of at least two hours and a half.

- All members of the Club who cannot furnish a reasonable excuse for absence at all practice games shall be fined $2.50 and expelled for the second offense.

Contests between clubs were called match games as distinct from practice games and were arranged by a representative of the club, usually the president, who issued a written challenge in the local newspaper. This communication included details such as the date, time, and location of the match, along with any specifics about rules and the amount of any wager. The challenged club then issued their response in writing, either agreeing to the terms set forth or suggesting an alternative. Below is the communication between the presidents of the Spotted Tails of Vermillion and the Coyotes of Yankton, printed in the July 7 and July 14, 1870, issues of the Dakota Republican. It is not known if a mutually agreeable date was found.

|

A CHALLENGE YANKTON, July 6, 1870 To Dr. J. G Lewis, President Spotted Tails Base Ball Club: Sir: — The 1st nine of the “Coyote Base Ball Club” to play a match game of Base Ball at Vermillion, or any place that the latter may designate, on the 22d of July, 1870; game to commence at 2 o’clock P. M. The game to be governed by the rules and regulations of the National Base Ball Association. C. H. Edwards, President, Morris Taylor, Secretary. |

Vermillion, July 13, 1870 C. H. Edwards, President, Coyote Base Ball Club, Yankton; Dear Sir:-Individual engagements on the part of the members of the Spotted Tails Base Ball Club, will prevent us playing you on the 22d inst., as proposed; but we will play you a single game any time during the month of September, most convenient to you. Game to be governed by the new Base Ball regulations. J. G. Lewis, President, E. D. Baker, Secretary. |

The Missouri River, the route Lewis and Clark took to explore the area in 1804–06, bisects the Dakota Territory from the southeast to the northwest. The US Army built several forts along the river, stretching from Fort Randall, located on the south side of the river near the present-day South Dakota-Nebraska border, to Fort Buford near the Canadian border. Fort Randall was established in 1856 for the purpose of controlling the Teton Sioux Indians in the area and protecting the settlers moving west on the overland route known as the Oregon Trail.

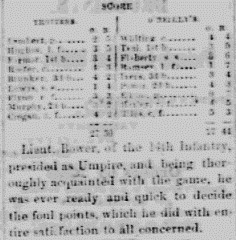

At Fort Randall, Lieutenant Thomas O’Reilly of the Twenty-second Infantry formed a base ball club at the post in 1870. They played three games against another team formed at the fort, the Trotters of the Fourteenth Infantry. The report of one contest between the teams played on July 9 was the first time a box score appeared in a newspaper in the Dakota Territory.5 The Trotters held a 29 –19 lead after seven innings, but the O’Reilly’s rallied for twenty-five runs in the final two innings to take a 44–30 win. The box score was simple and concise in its design. It listed the name of the umpire (along with a comment about his judgment and impartiality) and the names and positions of the players. The only statistics after the players’ names were an “O” and an “R” for outs and runs. Then, as today, the two most important elements in determining who wins baseball games are outs and runs.

The box score of the July 9, 1870 Trotters/O’Reilly’s match, the first known in a Dakota Territory newspaper, Dakota Republican, July 17, 1870.

After his team defeated the Trotters, O’Reilly issued a challenge to the Yankton Coyotes to play a match game at the fort in early August and wagering a new bat and ball. Traveling in carriages and crossing the Missouri River by boat, the Coyotes took two days to traverse the 60 miles west to the fort. The host O’Reilly’s believed they had secured a win when they scored 17 runs in their half of the ninth inning, but the Coyotes came back with five runs of their own, winning 49–48 with the deciding run scoring on a muff by the O’Reilly’s right fielder. Betting, which was common among the spectators at games, was said to be “spirited.” The newspaper account also noted that wagers were not confined to men, saying, “…even the ladies who were present took such an interest in the game that they promised each other certain articles in the dry goods line if such and such should come to pass.”6

After a lunch break and rest period in which participants indulged in lemonade and “such,” the Coyotes took on the post’s other team, the Trotters. The Coyotes, “petered out through overexertion” (or drinking “such”) dropped the game to the Trotters 28–12 in five innings. Holding a club to a dozen runs in five innings was considered a strong pitching performance at the time. Hence, the Trotters’ hurler Lieutenant W.H. Bowers, who also umpired the first game and “rendered entire satisfaction by his prompt and fair decisions,” was singled out for his ability to pitch the ball with lightning speed. Bowers—also said to catch and bat well—displayed this prowess despite having lost his left arm in battle, presumably during the Civil War.

The Coyotes, along with O’Reilly, Bowers, and other officers of the Twenty-second and Fourteenth Infantries, then retired to the post dining room “decorated with American flags and fitted up in a gay and festive manner” for a grand dinner. The table was reportedly “ladened (sic) with all the solid delicacies of the land, backed up with supplies from eastern and southern markets”. After dinner,

Corks began to ‘pop’ but most singular to relate not one of the contestants were wounded or disabled during the entire action, which was spirited and lasted until an early hour. The Coyotes were too much fatigued to hold up their side of the game with success, so far as speeching (sic) and singing was concerned, but at drinking lemonade they showed a remarkable capacity and solid judgment.7

This last was likely a comment on their ability to hold their liquor. After spending the night, the Coyotes, despite being a trifle tired and sleepy, started for home the next morning “happy and gay.”

After a tune-up game in which they defeated the Spotted Tails, 52–20, the Coyotes issued a challenge to another strong team in the vicinity, the White Caps of Sioux City, Iowa. The White Caps accepted, and a home-and-home series was scheduled for mid-October with the first game to be played in Sioux City. On Saturday October 15, the White Caps beat the visiting Coyotes 35–17 in a game called after eight innings due to darkness. The Sioux City paper said the Coyotes “took their defeat with good right grace”8 and although the report in the Yankton paper stopped short of making any excuses (the Coyotes were playing without three of their first nine), the reporter did say that a cold, blustering northwest wind “had such an effect on them they never played so poorly since the club was organized.”9

An unnamed writer in the Yankton Press summed up the base ball fever taking place in the region by editorializing the following:

Base Ball in the United States has gained a national celebrity, so much that every city, town, and village in the country has one or more base ball clubs. They have become almost as much of a necessity as newspapers and it is a question of about equal merits. Which is the best advertisement for a town – a first class newspaper, or a first class base ball club? For our part, we are inclined to one is as good as the other and a little better. Sioux City and Yankton, not to be outdone by their sister cities, have what they term, first rate clubs – clubs that have, to use a slang expression “cleaned up” everything in their respective localities and who have long felt a desire to cross bats with each other for the championship of the Northwest.10

The White Caps then traveled by stage coach to Yankton the following week to resume their series. Arriving late Thursday night, they stayed at the St. Charles Hotel and were greeted by the proprietor, M.A. Sweetser.11 He reportedly showed them to their rooms and provided them “something called ‘a night cap’, (an article of clothing you will understand).”12 The teams gathered on the grounds the next morning and again played in a chilly north wind, but the Coyotes “retrieved their lost laurels and covered themselves all over with base ball glory”13 by squaring the series with a 56–25 win.14 After the game, the White Caps returned to the St. Charles where Sweetser, “extended hospitalities in the shape of something calculated to warm our chilled blood and raise our depressed spirits.”15

That night, the Coyotes staged a ball at the Stone (School) Hall in honor of their guests (and their ladies) and even invited their rivals, the Spotted Tails, to come over from Vermillion for the event. The citizens of Yankton raised $300 to ensure the Coyotes could properly entertain their guests. The Yankton Press and Dakotan said of the event,

The Hall was beautifully decorated with flags and at the east end of the Hall, over the stage, were the words WELCOME WHITE CAPS AND SPOTTED TAILS in large letters… the music was splendid, and lovers of the dance very numerous. Over 50 persons were on the floor every set. It was, without an exception, the grandest and most festive occasion ever held in Yankton.16

The Yankton Press noted, “The members of the visiting clubs were as gentlemanly and social a body of men it has ever been our good fortune to meet, and we hope the day is not distant when they will be called again to come this way.”17

Daylight peeped through the windows before the festivities were over, but at some point during the evening it was decided to gather at the grounds at 10 A.M. the next morning for a third and deciding game of the series. The wind was blowing again, and because of the way the grounds were laid out, the wind blew in the face of the pitcher and favored the batters. This yielded predictable results. The White Caps scored twenty-three first inning runs, but the Coyotes battled back and eventually won the six-hour marathon 99–77. As was customary, they were awarded the championship ball and declared themselves the champion base ball team of the Northwest.18 The White Caps were gracious in defeat saying of their opponents, “…they deserve it for a more gentlemanly, entertaining, and courteous set of boys we have never met than the Coyotes of Yankton.”19

Members of the champion Coyotes came from all walks of life. Outfielder William Gould was a riverboat pilot; third baseman Thomas Duff operated a meat market; and first baseman Al Wood ran a jewelry store in Yankton. Arthur Linn, who was the starting pitcher in the second game of the Sioux City series, was a newspaperman. He had arrived in Yankton that spring from Iowa, took charge of the editorial department of the Yankton Press and Dakotaian, and eventually bought controlling interest in the paper. Nothing is known about Linn’s background in base ball, but he was described as, “…an intelligent, honest, and upright man, and a true Republican.”20 The Coyotes’ most talented player may have been teenage outfielder Charlie Delamater who was often singled out in game stories for his wonderful ability as a “fly catcher.” He died less than three years later, at age 19, of consumption.

The Spotted Tails organized again in April 1871, butlater in the summer changed their name to the Red Caps. In June, a second base ball club that had been started in Vermillion, the “Early Risers,” challenged the Red Caps to a match game on the Fourth of July. The challenge was accepted and the game, “witnessed by a very large concourse of both ladies and gentlemen,” was won by the more experienced Red Caps, 52–16.

Interestingly, the Vermillion paper listed base ball as one of the many vices encroaching on an otherwise civilized society. They wrote,

Dakota has improved vastly in advancing and ennobling influences during the last year or two. Now it is well known that certain institutions are invariably concomitants of highly civilized and cultivated communities, and they never go beyond them, and that where society is nearest its highest perfection, there do they most abound. We speak of gambling houses, brothels, base ball, horse racing, billiard matches, seduction, divorces, prize fights, murders, and similar institutions.21

The Red Caps challenged the Reserves of Minnehaha to a game in Sioux Falls later in 1871 and the journey, described in great detail in the Dakota Republican, provided an example of hardships encountered during overland travel at the time. The “jolly crew” set off from Vermillion early on Monday, August 7, in two wagons, their singing attracting the attention of passersby looking for their homesteads. After a break at 3 P.M. to eat dinner and rest the horses, the party set off again and estimated they had covered about 30 miles before stopping for the night around 10 P.M. They spread blankets, bison robes, and coats on the prairie grass, but swarming mosquitoes made it impossible for anyone to sleep. They set off again a couple of hours later, reached the small town of Canton around sunrise and, after stopping for breakfast, pushed on the final fifteen miles to Sioux Falls, arriving at 3:00 the next afternoon.22

Following a good night’s rest at the Hotel de Sioux Falls, the group went to the grounds that afternoon where the Reserves edged the Red Caps 37–36. The Red Caps then challenged the Reserves to a match at their grounds in Vermillion for September 28. The Red Caps turned the tables, defeating the Reserves 71–35, and afterward, the Red Caps offered to play the Reserves the next day, and “victory again perched upon the banners of the Red Caps,” again winning 61–33. The Dakota Republican wrote, “The best of feeling existed between the clubs during both entire games, and they parted on as excellent terms as they met.”23

Having beaten the Sioux Falls club two of three games and “every other club they have played in a match game” the Red Caps laid claim to the championship of the Northwest. The Coyotes of Yankton, the previous year’s champion, also claimed to have gone undefeated, including wins over the Red Caps. The Vermillion paper acknowledged as much, but argued because those Yankton wins were when the team was still called the “Spotted Tails” early in the season, technically, the Coyotes had not defeated the Red Caps. Further, the Red Caps claimed that every time they challenged the Coyotes to a match game, they failed to accept, which, to their minds, counted as a win for them and a loss for the Coyotes.24

Over the next three years the Yankton Coyotes, the Vermillion Red Caps, and a number of other clubs continued to operate, but the respective cities’ newspapers provided little coverage of the teams. Clubs in the area came up with some colorful nicknames. Two nines, presumably soldiers, named the “Dirty Stockings” and the “Government Socks” played a match at Fort Sully (near present-day Aberdeen, South Dakota) in 1870. Over the next couple of years a second club, the “Black Hillers,” formed in Yankton and the Clay County “Plow Boys,” the “Sleepies” of Maple Grove, and the “Hole in the Stockings” of Lincoln Center had match games. A few years later, in another matchup between military nines, the “Hard Scrables” (sic) defeated the “Never Sweats” 43–22.25

By the mid-1870s, both members of base ball clubs in the Dakota Territory and their fans became more knowledgeable about the game. The Yankton Press and Dakotaian printed scores of games of the National League, a professional major league formed in 1876 among cities in the eastern United States. The scores of these games were much lower than local games where teams routinely scored forty or fifty runs, so they began to equate low scores with better, more skilled play. The result of a Yankton game in 1873 was reported as a ratio, saying the score was 3–1 when actually it was 45–15. The relatively low score in a 17–2 win by Yankton over the Black Hillers prompted the game report to comment, “…the play of both clubs was very good, as the small score will show.”26 The summary went on to emphasize that Yankton only committed six errors in the contest.

|

A couple of steamboat rooters got into a dispute this morning over the relative merits of the Yankton and Vermillion base ball clubs, and supplemented the argument with a rough and tumble fight, in which hands, feet, teeth, and stones were used, and a considerable amount of blood spilled. —Yankton Press and Dakotaian, July 3, 1875 |

In July 1875, the Yankton Press and Dakotaian caught wind of an item in the Sioux City Journal stating that the Sioux City club had “frightened all base ball nines (including, it was implied, the home town Yanktons) by their play.” That report called for a response from Yankton, who dared Sioux City to issue a challenge. Sioux City promptly did and Yankton immediately accepted. Plans were made for three games, the first of which was to be played at Yankton on July 22. The Yankton Base Ball club quickly put together a social party to host the Sioux City club when they arrived, and took the unusual step of selling $1 tickets to defray expenses.

The visitors arrived by freight train on the day of the game and immediately went to the Douglas Avenue grounds, the home field of the other club in Yankton, the Black Hillers. “A large and fashionable attendance, a large proportion of which were ladies…”27 saw Yankton beat Sioux City 29–17. Although the Yankton Press was complimentary of their opponent’s skill and gentlemanly behavior, they did comment that score was as close as it was only because the Sioux City club was a picked nine, made up of the best players in the city.

Two weeks later Sioux City called off a return game claiming their grounds were in poor condition due to the presence of weeds. The Yankton paper pointed out that this state of disarray contradicted an earlier statement in the Journal which said, “Our ball tossers [Sioux City] claim to have the best grounds west of Boston. They are located near the foundry. The runs between the bases have all been leveled by the removal of sod.”28 The two teams were again scheduled to meet in early September at a base ball tournament held during the Vermillion Harvest Festival.29 Rain fell the morning of the game and, according to one member of the Sioux City club, when they arrived at the grounds they found them “…in fair condition without a particle of water standing thereon.”

The Yankton club’s assessment was different, saying that the grounds were “covered with two inches of water” and they convinced the festival committee to postpone the game until the next day. Sioux City could not stay in Vermillion another day, so Yankton played and beat Springfield, another team entered in the tournament, 23–5 to take home the $75 first prize.

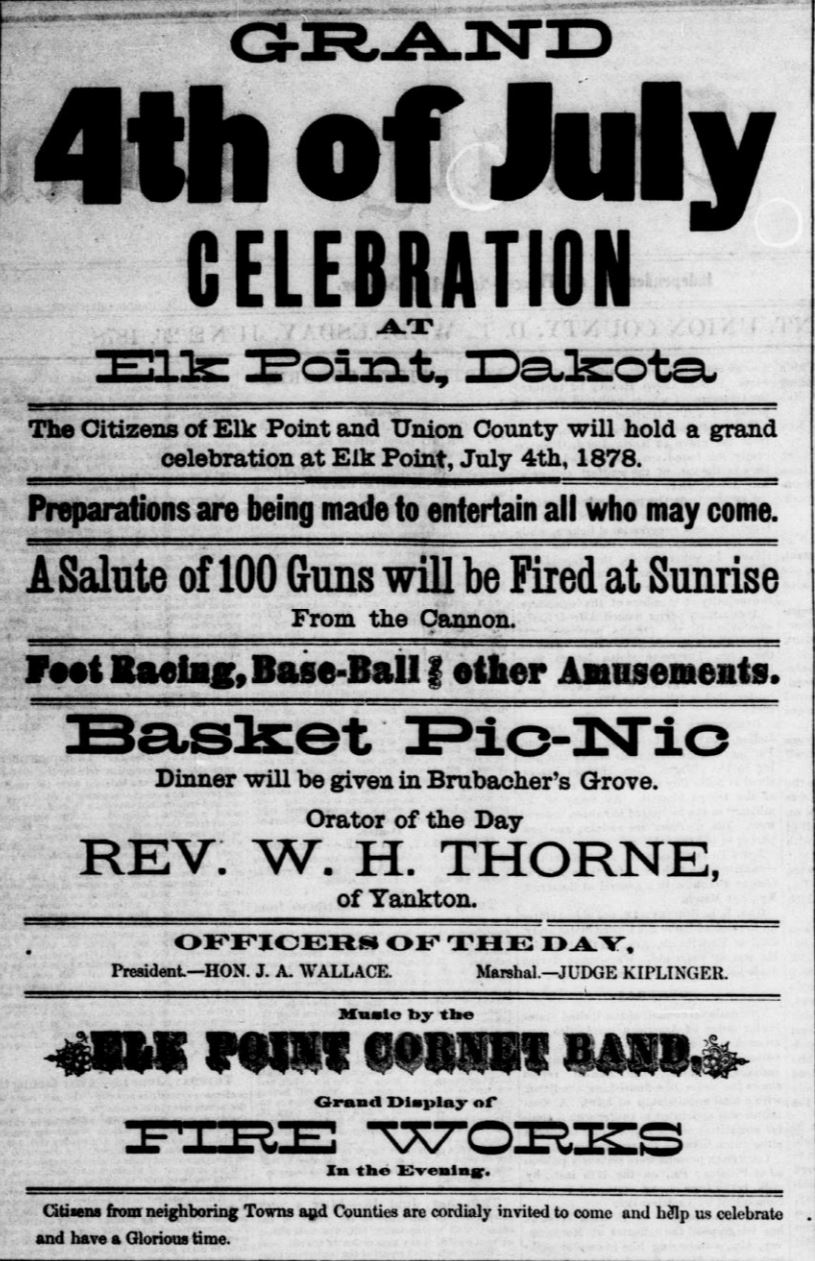

Base ball was one of the events at early July 4 celebrations in the Dakota Territory, Union County (D. T.) Courier, June 26, 1878

The goodwill and friendship that had existed between the two clubs a few years earlier was now strained by the incident in Vermillion. According to the Sioux City players, the “lack of pluck” in the Yankton club caused the failure to play the game. Yankton countered that Sioux City failed to pay their entry fee for the tournament and “came up here almost unannounced and stood around in the rain all day.” They went on to say that Sioux City’s refusal to play was a pretext to “get out of their contract and sneak away to their homes.” The Dakotaian added, “They [the Sioux City club] are about as contrary and unreasonable a set as the other Sioux on the reservation.”30

Despite the hard feelings, the teams made one more effort to play again when Yankton challenged Sioux City to a match game to be played at Vermillion in early October, and upped the ante by suggesting they play for any amount from $100 to $500 a side, provided the clubs play with the same nine men they entered at the tournament. Sioux City was not willing to accept those terms because it was rumored that they had brought in a professional pitcher from the east.31

In their detailed response, Sioux City essentially said that the original agreement was for a three game series with the first game held in Yankton, the second in Sioux City, and the third, if necessary, at a neutral site in Vermillion. Their denial went on to say that if Yankton wanted to come to Sioux City, they would gladly play them, but they had no intention of going back to Vermillion after what had happed there during the Harvest Festival tournament. No record could be found of any more games between Yankton and Sioux City that year, nor in any subsequent seasons in the decade.

Earlier that summer, in June of 1875, three companies of the Seventh Cavalry were sent to Fort Randall “to be actively employed guarding the entrance routes to the gold fields,” while the remaining six companies stayed back at Fort Abraham Lincoln. Two base ball clubs, the McDougals and the Benteens, were among the members of the Seventh Cavalry sent to Fort Randall.32 According to one report, while there, each played a game against the post team, the Randalls.33The report also implied that these were the first games between teams of the two army forts.34

The Benteens returned to Fort Randall again in September and easily beat a picked nine of the Seventh Cavalry 39–6. The writer, Theodore Ewert (who signed his article T.O.D.), remarked, “…neither club played up to their high standards owing to the high wind.”35 A few days later the Benteens dropped a game, umpired by Ewert, to a picked nine at Fort Randall 12–9, but Ewert said, “It is hoped that these two nines will meet again soon as a large amount of money will probably change hands at such an event.”36

Later that summer the Randalls changed their name to the Lugenbeels, in honor of Pinkney Lugenbeel, commander at the post. After racking up a series of wins against area rural nines, and after the Yankton/Sioux City series fell through, the Lugenbeels challenged Yankton to a game to decide the championship of the Northwest. The soldiers had to schedule games around their military duties, so when they informed Yankton of available dates, Yankton told them they had planned a tour through Sioux City, Omaha, and Council Bluffs during the proposed dates, so they would be unavailable. It was later learned that Yankton had no such tour scheduled, which resulted in accusations they were ducking the Lugenbeels. They finally agreed to a match game October 28, 1875, but there is no record of the game having taken place.

|

“A base ball game played yesterday at the foot of Third Street between two steamboat nines—the “Galoots” of the C.K. Peck and the “Lunch Grabbers” of the Nellie Peck. James Spargo was scorer. The result of five innings gave the “Galoots” 37 and the “Lunch Grabbers” 11.” — Yankton Press and Dakotaian, August 25, 1877 |

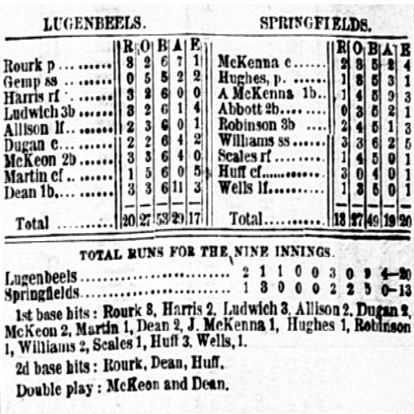

The Yanktons and Red Caps of Vermillion continued to field teams over the next few years. The Coyotes noted that they had secured the services of some eastern players that would make the strongest nine they had ever had, but no record could be found of the two clubs facing each other. By the end of the decade, the Lugenbeels of Fort Randall emerged as the top nine in the region with their main rival being Springfield, another small community on the Missouri River. They faced off on July 4, 1879, in Springfield with the Lugenbeels scoring nine runs in the seventh inning and four more in the eighth to take a 20–13 victory. On the trip back to the fort, the wagon carrying the Lugenbeel players overturned and right-fielder Harris sustained a broken leg. Upon arriving at the post hospital, the army surgeon amputated the leg, but Harris died the next day.

Throughout the decade of the 1870s, box scores gradually added more details. The summary of an early Yankton/Sioux City match included the names of fielders participating in double plays and a count of the number of “fly catches” for each fielder, possibly an indication of the difficulty and rarity of those events in early base ball. The box score for the Lugenbeel/Springfield match described above added an inning-by-inning line score, and the names of the players making first base hits and second base hits. In addition to “R” and “O” (runs and outs) tallies for each player, a “B” (presumably for bases), and an “A” and “E” (assists and errors) were added. Springfield was charged with twenty errors in the game while the winning Lugenbeel squad only committed 17.

A box score from the Lugenbeel/Springfield game July 4, 1879, including the ill-fated Harris, batting third for the Lugenbeels, Yankton Press and Dakotaian, July 17, 1879

The Lugenbeels next defeated a club from Niobrara (across the Missouri River in Nebraska), 29–18 and then won a return match in Niobrara a few weeks later. In addition to the usual compliments about hospitality and goodwill that accompanied game stories, the reporter felt the need to add that if the two clubs met again, “…your [Niobara’s] windy pitcher should practice and be able to deliver the ball from below the hip and from the shoulder,”37—implying that he had used an illegal overhand delivery. Nonetheless, the Yankton Press and Dakotaian said of the Lugenbeels, “In the base ball line, they are the best in Dakota.38

A devastating Missouri River flood in the spring of 1881 wiped out much of the cities of Vermillion and Yankton, and consequently little base ball was played over the next couple of years. However, the game had gained a foothold, and as new settlements sprang up with the expansion of the railroad, scores of communities in the Dakota Territory boasted base ball teams by the mid-1880s. By then, base ball was well established in the mining camps in the Black Hills of present day South Dakota.39 The ball club from Aberdeen traveled all the way to St. Paul, Minnesota, for a game in 1883, and the 1887 Watertown “Invincibles,” who were said to employ five outside players, considered themselves the undisputed champions of the Dakota Territory.40

Although the population has always been too small to support professional baseball except in the lower rungs of the minor leagues, since its origins in the 1870s, semipro and amateur baseball has been played with as much interest and enthusiasm in North and South Dakota as anywhere in the country.

TERRY BOHN is an original member of the Halsey Hall SABR Chapter in Minnesota. He has previously been published in the Baseball Research Journal, has written numerous biographies for the SABR BioProject, and has completed three books on baseball history in North Dakota. His other interests include the Negro League Baseball Grave Marker Project. He works as a hospital administrator in Bismarck, North Dakota.

Notes

1 Terry Bohn, “Many Exciting Chases After the Ball: Nineteenth Century Base Ball in Bismarck, Dakota Territory,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Volume 43, Issue 1, Spring 2014.

2 See Tim Wolter, “Boots and Saddles: Baseball with Custer’s Seventh Cavalry”, The National Pastime, Society for American Baseball Research (SABR), Number 18, 1998, Larry Bowman, “Soldiers at Play: Baseball on the American Frontier”, Nine: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture, Volume 9, University of Nebraska Press, January, 2000, and John M. Carroll and Dr. Lawrence A. Frost, Private Theodore Ewert’s Diary of the Black Hills Expedition of 1874, CRI Books, Piscataway, NJ, 1976.

3 https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/1869_Cincinnati_Red_Stockings

4 “B B Club,” Yankton (D. T.) Press and Dakotaian, March 10, 1970.

5 “The Boys in Blue and the National Game,” Dakota Republican, Vermillion, D. T., July 14, 1870.

6 “Base Ball,” Yankton (D. T) Press and Dakotaian, October 19, 1870.

7 “Base Ball at Fort Randall, the Games and the Result,” Yankton (D. T.) Press and Dakotaian, August 11, 1970.

8 “Base Ball,” Sioux City (IA) Journal, October 16, 1870.

9 “Base Ball,” Yankton (D. T) Press and Dakotaian, October 19, 1870.

10 “Base Ball – Sioux City vs. Yankton – The Latter Victorious,” Yankton (D. T) Press and Dakotaian, November 2, 1870.

11 Sweetser was often selected to umpire local games. One report (Yankton Press and Dakotan, September 7, 1870) indicated that he was an old base ballist, having been an active member of the Olympics of Washington, D. C. for two or three years. No other documentation could be found to substantiate that claim.

12 “The ‘White Caps’ at Yankton, Base Ball Championship!, The Coyotes Hold the Championship of the North-West!!!, The White Caps Defeated,” Dakota Republican, Vermillion, D. T., October 27, 1870.

13 “Base Ball,” Yankton (D. T) Press and Dakotaian, October 26, 1870.

14 Yankton (D. T) Press and Dakotaian of October 27, 1870, had the score 56–23.

15 “The ‘White Caps’ at Yankton,” Dakota Republican, Vermillion, D. T., October 27, 1870.

16 “The ‘White Caps’ at Yankton,” Dakota Republican, Vermillion, D. T., October 27, 1870.

17 “The ‘White Caps’ at Yankton,” Dakota Republican, Vermillion, D. T., October 27, 1870.

18 Usually, just one ball was used in match games. The tradition was for the winning team to take possession of the ball.

19 “Base Ball – Sioux City vs. Yankton – The Latter Victorious,” Yankton (D. T) Press and Dakotaian, November 2, 1870.

20 Yankton (D. T) Press and Dakotaian, April 7, 1870.

21 “Civilization,” Dakota Republican, Vermillion, D. T., June 15, 1871.

22 “A Trip to Sioux Falls,” Dakota Republican, Vermillion, D. T., August 17, 1871.

23 “Base Ball,” Dakota Republican, Vermillion, D. T., October 5, 1871.

24 Dakota Republican, Vermillion, D. T., October 19, 1871.

25 Yankton (D. T) Press and Dakotaian, July 10, 1879.

26 “For the Championship,” Yankton (D. T) Press and Dakotaian, July 16, 1875.

27 “29 to 17, But Unfortunately the Large Figures Adorn the Yankton’s Club Score, The Uncertainty of Base Ball as Exemplified at Yankton Yesterday”, Sioux City (IA) Journal, July 23, 1875.

28 “Base Ball Grounds,” Yankton (D. T) Press and Dakotaian, July 31, 1875.

29 Early harvest festivals, like the one held in Vermillion, would eventually evolve into county fairs.

30 “NOW STOP YOUR TALK, Or Come Forward and Cover the Little Sum Dedicated to the S. C. B. B. Club,” Yankton (D. T) Press and Dakotaian, October 4, 1875.

31 Yankton (D. T) Press and Dakotaian, October 10, 1875.

32 Army teams were usually named after the captain, or the highest ranking officer on the team.

33 The author of the article signed it T. O. DORE, no doubt Theodore Ewert.

34 “From Randall, Custer’s Cavalry to Do Police Duty Instead of Searching for More Hidden Treasure – Base Ball Notes,” Yankton (D. T) Press and Dakotaian, June 7, 1875.

35 Yankton (D. T) Press and Dakotaian, September 6, 1875.

36 “For Randall, A Good Game of Base Ball,” Yankton (D. T) Press and Dakotaian, September 10, 1875.

37 “Fort Randall,” Yankton (D. T) Press and Dakotaian, August 11, 1879.

38 “Fort Randall,” Yankton (D. T) Press and Dakotaian, August 11, 1879.

39 David Kemp and Michal Runge, Baseball in the Mining Camps: A Deadwood Baseball Book, Mariah Press, 2016

40 Watertown (D. T.) Public Opinion, June 17, 1887.