Damn Yankees

This article was written by Rob Edelman

This article was published in

IN 1954, the Washington Senators were an abominable team They finished the season ensconced in sixth place in the American League, with a 66—88 record. The previous year, they were a fifth-place ballclub, completing the campaign at 76—76. In 1952, they also ended up in fifth place, with a 78—76 mark. In mid-decade, Ernest Barcella, a Washington-based political writer and avid Senators fan, observed, “The Washington fan is a strange breed—eternally optimistic, long-suffering, but readily forgiving. ‘You can’t win ’em all,’ he shrugs. Let the team win four in a row . . . and the rooter lovingly labels his heroes ‘Super Nats.’”

Rarely did the Nats win four in a row in the 1950s—and none of the regulars on that 1954 club are enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame. (Harmon Kille- brew, he of the tape-measure homeruns, debuted that season, but appeared in just nine games. In thirteen at-bats, the eighteen-year-old had four hits.)

But there was hope for the Senators—at least in the world of fiction, the world of baseball fantasy. That year, a writer by the name of Douglass Wallop—a perfect name for the author of a baseball book—published The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant, a comic-melodramatic novel about baseball, sex, and restored youth. In the story, the mighty Bronx Bombers, who just completed a still-unprecedented five-year run as World Series champions, are dethroned by a Washington Senators nine led by an unlikely phenom: Joe Boyd, a portly fanatic who makes a pact with the Devil and is transformed into Joe Hardy, a strapping home-run hitter and savior of the D.C. baseball club. A half-century later wrote Jonathan Yardley in the Washington Post, Wallop’s story “is by now as deeply embedded in American legend as is Goethe’s ‘Faust’ in German legend.”

In 1956, The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant was transformed into a hit Broadway musical, Damn Yan- kees: a title that remains melodious to the ears of Yankee-haters of all eras. Two years later, Damn Yankees was adapted to the screen and released by Warner Bros. The story that evolved into Damn Yankees was the brainchild of Wallop, a Washingtonian, University of Maryland graduate, and long-suffering Senators fan. A journalist as well as a novelist, Wallop, who was born in 1920 as John Douglass Wallop, authored 13 novels. Among them were Night Light—his first, published in 1953—and his last, The Other Side of the River, which came out in 1984, a year before his death. Baseball: An Informal History, his one work of nonfiction, hit bookstores in 1969. Inarguably, however, The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant, which Wallop wrote after Night Light, remains his most celebrated and enduring work. On his death, the novel had sold over 2.5 million copies.

Wallop’s yarn opens on July 21, 1958, four years in the future. The Bronx Bombers are solidly ensconced in first place, on their way to their tenth consecutive pennant. (Clearly, the story was penned before the Cleveland Indians won the ’54 AL flag.) It was the Yankees’ style, according to Wallop, “never to patronize or belittle the opposing team They courted you

with good fellowship and then beat your brains out.” On that July day, the Senators are a sixth-place ball- club, closer to falling to seventh place than rising up to fifth.

Joe Boyd is a 50-year-old real-estate salesman, an Average Joe who lives quietly in the Washington suburb of Chevy Chase. An armchair player-manager-coach, Boyd agonizes as his beloved Nats wallow in the second division. On that midsummer evening, after offhandedly declaring that he would sell his soul in exchange for a slugger who would reverse his team’s fortunes, he is recruited by the glad-handing, nattily attired Mr. Applegate, aka the Devil. In exchange for selling his spirit to Applegate—but with an escape clause, allowing him to opt-out of the deal by Septem- ber 21—the years peel off Boyd and he is transformed into Joe Hardy, strapping 22-year-old Boy Wonder.

Hardy is quickly signed by the Senators and, in less than two months, bashes 48 homers and compiles a

.545 batting average. He becomes a celebrity, a national phenomenon. But Joe is lonely. He misses his home and his devoted wife, Meg. In order to lure him into keeping the contract, Applegate provides him with a companion: the lovely Lola, a seductress and Applegate underling who once was the ugliest woman in  Providence, Rhode Island, and who has agreed to eternal damnation.

Providence, Rhode Island, and who has agreed to eternal damnation.

With Hardy leading them, the Senators become a top contender to wrest the AL flag from the Yankees. But further complications arise as Gloria Thorpe, a skeptical sportswriter—and, given her gender, a rarity for the era—investigates Hardy’s personal history. Meanwhile, Applegate not only schemes to hold Boyd to the contract but plots to have the Yanks edge out the Senators for the flag.

Although The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant is pure whimsy, Wallop does include real-life baseball references. At one point, for example, the Yankees come to Griffith Stadium to play the Nats. In one of the games, Joe Hardy smashes a “titanic clout” that soars over the center-field wall. Previously, Wallop re- ports, only three other major leaguers had achieved this feat: Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Larry Doby.

Granted, Wallop had been a lifelong Senators fan, but not all sports enthusiasts, even those who are professional writers, come to author classic baseball stories. Wallop readily admitted that he conjured up the plot on nothing more than “inspiration, a brainstorm.” According to Mark Judge, the grandson of Joe Judge, the writer based the Joe Boyd/Joe Hardy character on the longtime Nat who manned first base in 1924, the year they won their lone world championship. “For several years in the late 1940s, Wallop dated Judge’s daughter, my Aunt Dorothy,” he noted in 2004. “Now in her 70s, she recalls that Wallop ‘was steeped in Senators history’ and would spend hours exchanging stories with her father at their house in Chevy Chase, Maryland.” Judge added, “My grandfather apparently watched baseball games and talked back to the television, indignant at the Senators’ poor play. That scene is recreated in the opening of the Broadway and Hollywood productions of Damn Yankees. ‘That man was my father,’ my father would say whenever the film was on TV.”

It took Wallop three months to pen The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant, which he finished in one draft. Conversely, he had labored over Night Light for four years. Sunken Garden, the novel he wrote after The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant, took him three years to complete.

On June 14, 1954, the New York Times announced that “Big-league baseball and the Faust theme are the ingredients of a novel by Douglass Wallop that Norton will publish July 13. The protagonist is a tired, middle-aged, fattish and fervid fan of the Washington Senators. Through the offices of the Devil, he becomes ‘the greatest and most unnatural’ outfielder in baseball history. The story, which begins with the Yankees well on ‘their despised way’ to a tenth straight pennant, has been titled ‘The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant.’”

The novel earned sparkling reviews. Charles Poore, writing in the New York Times, raved, “Mr. Wallop’s breezy fable is the best use of the legend of the man who sold his soul to the devil since Thomas Mann, and the best baseball story since Ring Lardner.” Added Gilbert Millstein, also in the Times, “In an era when the handling of humorous fantasy is . . . pretty generally humorless and almost certainly fantastic, [this book] stands out as authoritatively as a .400 hitter on the Pittsburgh Pirates. Through the extremely complex devices of writing well and refusing to make

his point more than once, the author has avoided the excessive archnesses and the groaning injunctions associated with a project of this kind.”

The book sold briskly, and was snapped up by the Book-of-the-Month and Reader’s Digest mail-order book clubs. References to it began appearing in the media. On September 19, an anonymous New York Times writer humorously noted, “Last week, as the Cleveland Indians were bringing to an end the Yan- kees’ five-year hold on the American League pennant and world championship, there were dark mutterings among Yankee fans that some of the Cleveland players had been playing all season like men possessed. But there was no real evidence, at least nothing that would stand up before a hearing before the Baseball Commissioner. As for the Senators, their hands were clean. They were still in sixth place.”

That same month, Harold Prince, a rising young stage producer-director, happened upon Wallop’s book. Most recently, Prince, along with Frederick Brisson and Robert E. Griffith, had co-produced the hit musical The Pajama Game, which had opened on Broadway in May. The Pajama Game had settled in for a lengthy run at the St. James Theatre; Prince, along with the show’s composer and lyricist, Richard Adler and Jerry Ross, was poring through dozens of books and manuscripts, vainly searching for a follow-up project. As he immersed himself in The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant, Prince became convinced that he had found it. One September evening, during a performance of The Pajama Game, Prince excitedly described the story to Adler and Ross. The duo crowded together in the back of the theater, and began looking over the book. They were as enthusiastic as Prince, and, before the end of the final act of The Pajama Game, the trio agreed to transform the book into a musical.

On September 28, it was revealed in the New York Times that Wallop’s book had been optioned for the Broadway stage. Brisson, Griffith, and Prince would produce the show. George Abbott, the legendary theatrical producer-director who had co-authored and co-directed The Pajama Game, would adapt the novel with Wallop. Abbott would direct, and Adler and Ross would pen the score.

Transforming the novel into a stage show was no simple process. “In writing the book,” Wallop explained, “the plot kept running away with me.” According to Abbott—who described the work-in-progress as the “first musical about baseball in Broadway history”—the novel was far too plot-laden for the stage. It needed to be pared down, with all

excess story elements eliminated. He divvied up the sections of the book, assigning some to Wallop and keeping others for himself. Occasionally, the two labored over the same sequence.

Furthermore, The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant was too long a name to fit on a Broadway marquee. It was Abbott who conjured up the title Damn Yankees, which he felt was dramatic and to the point. In 1955, the phrase “damn Yankees” was not uncommon. For example, in December 1954, reported The Sporting News, “Bob Turley, who had received a new automobile and $1,000 [because of his regard among fans] as a member of the Orioles last season, discovered how quickly his popularity dwindled when he walked outside his home the morning after he was traded to New York. Inscribed on the dust of his automobile trunk, the right-handed hurler found the words, ‘Damn Yankee.’<HR>”

Adler and Ross began work on the score when the final script was still a jumble of disjointed scenes. At their disposal was an outline penned by Abbott, Wallop’s book, and the constantly evolving script. The first song they completed was the first in the show: “Six Months Out of Every Year,” in which Meg Boyd and other baseball wives lament their husbands’ inat- tention during the baseball season. Even though the story told in Damn Yankees is pure fantasy— as much for the fact that the Washington Senators become a first-division ballclub as for its Faustian element—the show’s creators agreed to keep the narrative anchored in the real world. Thus, the New York Yankees remain the New York Yankees, and do not become the New York Knights (the fictitious team in Bernard Mala- mud’s The Natural). The Washington Senators are the Senators, and not the Representatives. The opening number references Willie Mays, who may not have been a Bronx Bomber—but it was easier to rhyme the Say Hey Kid’s surname. In the song, “Mays” is rhymed with “pays” and “plays.” It might have taken an Ira Gershwin or Lorenz Hart to conjure up a clever word or phrase to go with “Mantle.” Additionally, once the show reached Broadway, the voice of Mel Allen was heard onstage broadcasting several games—and describing the heroics of Joe Hardy.

The other Adler-Ross songs were employed to develop the characters, or communicate their feelings and views. They reflected on the spunk and spirit of the pre—Joe Hardy Senators (“Heart”), explained the “history” of Hardy (“Shoeless Joe from Hannibal, Mo.”), irreverently presented the coquettish Lola (“Whatever Lola Wants [Lola Gets]”), and allowed Ap- plegate to revel in his devilish past (“Those Were the Good Old Days”). In most musicals, the love songs involve passion between two young people. Adler and Ross found especially challenging the penning of the romantic songs in Damn Yankees, as they explore the emotions of Joe and Meg Boyd: a middle-aged couple, married for two decades, and their longing for each other after they are separated.

In addition to The Pajama Game, Adler and Ross, both native New Yorkers, had penned songs for the Broadway revue John Murray Anderson’s Almanac, which opened in 1953. They authored “Rags to Riches,” which became a number-one hit for Tony Bennett. But Damn Yankees would be their final collaboration. A few months after the show made its Broadway bow, Ross died of bronchiectasis, a lung dis- order. He was twenty-nine years old.

In early January 1955, it was announced that Damn Yankees would open at the Forty-sixth Street Theatre on May 5. In mid-month, the casting of Ray Walston as Applegate was announced. Walston was then appearing on the New York stage in House of Flowers, a musical. He would leave the show in early March, when rehearsals for Damn Yankees would begin.

From the outset, all the behind-the-scenes person-

Neil agreed that one actress, and one actress alone, could play Lola: Gwen Verdon, who had won acclaim in Cole Porter’s Can-Can in 1953. The red-haired Ver- don could dance up a storm, and was sufficiently sexy to play a siren. She was to emerge from Damn Yankees a full-blown star. Stephen Douglass, who had replaced John Raitt as the male lead in The Pajama Game, was cast as Joe Hardy.

Bob Fosse, who choreographed The Pajama Game (and married Verdon in 1960), signed on to stage the dance sequences. Murray Schumach, writing in the New York Times, reported that Fosse “had to work out a ballet for baseball players, using movements from the game. A baseball fan—partial to the Cubs because he was born in Chicago—he considered, for a time, working in the liquid movements of the double play. He found this impractical, though theatrical. However, with the hoedown rhythm dictated by the music he worked in the motions of batting, pitching, fielding, and sliding and tossed in a sort of juggling act with baseball bats.”

William and Jean Eckart, the show’s set and costume designers, created a grandstand section and the Senators’ dugout and locker room by researching at the New York Public Library and from images provided them by the Senators ballclub. The Eckarts also designed a show curtain consisting of 1,645 major-league baseballs attached by colored cords.

The principal actors began rehearsals on March 7. All went smoothly and, prior to opening on Broadway, Damn Yankees played out-of-town previews—the the- atrical equivalent of spring training—in New Haven and Boston. In mid-April, the Yankees were battling the Red Sox in Beantown, and it just so happened that Damn Yankees was playing there. To drum up press for the show, the Yanks were invited to attend a preview. Quite a few of the players showed up, including manager Casey Stengel. Soon afterward, when asked to venture an opinion about the show, the skipper barked, in pure Stengelese, “I ain’t gonna comment about a guy which made $100,000 writin’ about how my club lost.”

It was around this time that an outlandish-sound- ing musical number was deleted from the show. Reportedly, it was a ballet featuring a gorilla garbed in a New York Yankees uniform and dancers dressed in Baltimore Orioles—like bird costumes.

The Damn Yankees company returned to New York and, on the first of May, Murray Schumach described the scene as the show “went into the final phases of frenzied change and rehearsal”: On the stage, accompanied by a pit piano with the drive of a pneumatic drill, singers chorused almost by the syllable. Behind them, indifferent to the music, dancers spun, leaped and shouted with wanton energy. In the lobby, actors bellowed lines up wide staircases to the lofty roof of the echoing theatre. Up and down the aisle, between stage and lobby, raced the resonant voice and long legs of Mr. Abbott, shaving off minutes from the show as a boxer sweats off ounces as the bout nears.

Damn Yankees premiered on Broadway on May 5. The opening night tickets were designed to resemble tickets to a ballgame, complete with date, gate, and seat numbers, and even rain-check specifications. Just as Wallop’s novel, Damn Yankees received rave re- views. Lewis Funke, writing in the New York Times, began his critique by noting that the show was “as shiny as a new baseball and almost as smooth.” He ended his first paragraph by pronouncing, “As far as this umpire is concerned you can count it among the healthy clouts of the campaign.” Funke dubbed Ver- don “alluring” and “vivacious,” described Walston’s performance as “impeccable,” and “authoritative and persuasive,” and noted that Douglass made “a completely believable athlete.” He declared that Adler and Ross “have provided a thoroughly robust score” and that Fosse’s dance routines “are full of fun and vitality.” And he added, “But even the most ardent supporters of Mr. Stengel’s minions should have a good time.”

Writing in the New York Daily News, John Chapman called Damn Yankees “a wonderful musical. In it, Miss Verdon appears as a splendid comedienne, an extraordinary dancer and just plain fascinating person.” He added, “Old Manager Abbott, the Casey Stengel of the music-show business, has kept control of the whole show. His casting is unerring, as usual.”

Not all the show’s reviewers were professional theater critics. “The music and dancing routines are as slick as a Dark-to-Williams-to-Lockman double play,” pronounced Russ Hodges, the New York Giants’ play-by-play man, “and the lyrics have the wallop of a Ted Kluszewski.” Shirley Povich, the celebrated Washington Post sports reporter and columnist, noted that the show’s producers “got more baseball onto a stage than was believed possible. The dugout scenes are downright amazing for their faithfulness to the majors, even down to the correct piping of the suits.” The real Washington Senators, in fact, had donated game-worn jerseys that were employed as costumes. Povich added, “They do a shortstop ballet in ‘Damn Yankees’ that ought to win a pennant in that league.” Of the show’s female star, he commented, “Gwen is both the pennant and the World Series of Broadway play-acting.”

Povich took a more contemplative tone when he observed that New York theatergoers who found the show frivolously entertaining “wouldn’t understand, natu- rally, that ‘Damn Yankees’ is not a jesting term and that it is actually full of hate for the Yankees. They would understand. If they were Washington baseball fans. The play . . . is not a joke in two acts. The true Washington fan lives and dies and lives again with ‘Damn Yankees.’” Povich added, “How can you challenge the authenticity of Joe Boyd? [Is] there a Washington fan, middle-aged or otherwise, who has not yearned for that long-ball hitter for the Senators, or who has not envisioned himself as the Walter Mitty who could de- liver that long ball and beat the dratted Yankees at their own game? There is a Joe Boyd in every household in Washington, or maybe I should amend that to

say in every household worth calling a home.”

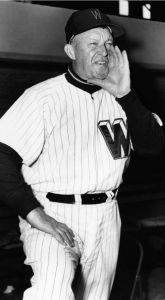

Not long after the show opened, the Nats came to New York to battle the Yankees—and the players were invited to see Damn Yankees. “They liked the show,” according to Povich, “especially Gwen Verdon, the devil’s damsel who puts on the locker room dance that the late Judge Landis would have outlawed.” Washington skipper Chuck Dressen was asked to take a bow from the stage. Years later, Mickey Vernon, the team’s

first-sacker and one of its few quality players, recalled that he and Dressen went backstage and had their picture taken with Gwen Verdon.

The Yankees, meanwhile, were collectively oblivious to the show. On September 14, 1955, New York Times columnist Arthur Daley reported that, even though the Bronx Bombers were mired in a mini-losing streak, “none of the ballplayers seemed to notice” when tunes from Damn Yankees began filling the air during batting practice at Yankee Stadium.

A month before, the Damn Yankees cast played a team representing Silk Stockings in a Broadway Show League ballgame, and lost by a 13—6 score. The Damn Yankees actors played the same positions as their characters, but with one exception. Stephen Douglass begged off participating, because he never before had played baseball.

The Broadway cast album of Damn Yankees became a best-seller. And the show earned seven Tony Awards, most significantly as Best Musical. Verdon was named Best Actress in a Musical. Walston and Douglass were pitted against each other as Best Actor in a Musical, with Walston emerging victorious. Russ Brown, cast as Benny van Buren, the Senators’ crusty manager, was named Best Featured Actor in a Musical. Fosse won for his choreography, as did conductor- musical director Hal Hastings and stage technician Harry Green. Rae Allen, playing Gloria Thorpe, was nominated as Best Featured Actress in a Musical.

Damn Yankees ran for 1,019 performances, closing on October 12, 1957; during its Broadway run, it moved from the Forty-sixth Street Theatre to the Adelphi. Meanwhile, the show’s national company traversed the U.S., with the celebrated stage clown Bobby Clark starring as Applegate.

Back in the 1950s, hit stage musicals regularly were adapted for the screen—and Damn Yankees was no exception. Warner Bros. purchased the rights to film the show with the studio, according to different sources, paying between $500,000 and $750,000. The celluloid version was codirected and coproduced by George Abbott and Stanley Donen, a veteran helmer of screen musicals. Frederick Brisson, Robert Griffith, and Harold Prince, the trio who mounted the stage show, were listed as associate producers. Abbott earned sole screenplay credit, The Eckarts designed the production and costumes, Fosse did the choreography (and also appeared on-screen as a mambo dancer), and most of the original Broadway cast recreated their roles. The major exception was Tab Hunter, who replaced Stephen Douglass as Joe Hardy. At the time, Hunter was a hot commodity in motion pictures—unlike Walston, Verdon, and the supporting players.

Interiors for Damn Yankees were filmed at Warner Bros.’ Burbank studios. Ballyard scenes were shot on location over ten days at Los Angeles’ Wrigley Field. According to Jonathan Yardley, a self-described “devout Yankee hater,” the minor-league ballyard was made up to look “for all the world like good old Griffith Stadium.” Meanwhile, in-game footage was filmed during the 1957 season when the Senators took on the Yankees at the real Griffith Stadium. This footage is edited onto the staging of the pennant-deciding game, and watching it today is great fun for Baby Boomers. Could that be Camilo Pascual on the mound for Washington? That must be Yogi Berra catching a foul popup. In the sequence, Joe Hardy/Joe Boyd makes a game-saving catch off the bat of none other than Mickey Mantle.

Hunter was cast primarily to ensure a healthy box office. But the film’s marketing campaign spotlighted the presence of Gwen Verdon. Its tagline was, “It’s a picture in a million! Starring that girl in a million, the red-headed darling of the Broadway show, Gwen Verdon!” Originally, the publicity featured Verdon posed in a baseball uniform. But in the mid-1950s, bats and balls did not necessarily translate to box-office gold. So the promotion was changed to emphasize the star’s sex appeal, with the theatrical poster highlighting a leggy, skimpily clad head-to-toe image of Verdon. In a number of non—U.S. venues, the film’s title was changed to What Lola Wants because foreign audiences would not understand the meaning of Damn Yankees.

As to plot, the film version adheres to the stage show. However, three musical numbers were deleted: “Near to You,” a love ballad (which was replaced by the similar “There’s Something About an Empty Chair”); “A Man Doesn’t Know,” a profoundly moving song that reflects on the feeling that lovers abuse love, and do not appreciate one another until after they are separated; and “The Game,” a semi-risqué comical routine in which some of the Senators recall how their sexual exploits are interrupted by thoughts of remaining true, pure, and in training.

For baseball fans, one of the highlights of the screen version of Damn Yankees is the dancing in the “Shoeless Joe from Hannibal, Mo.” number. Here, Bob Fosse’s expressive choreography incorporates pound- ing gloves, fielding grounders, tossing balls, and sliding into bases with the dance steps. Aficionados of classic 1970s television will savor hearing the distinctive voice of All in the Family’s Edith Bunker on-screen. Jean Stapleton, who also appeared onstage in Damn Yankees, employs it in her role as Meg Boyd’s friend, Sister Miller. She is a delight as she gets all aflutter upon meeting Joe Hardy—the Joe Hardy— and, later, sings a few verses of “Heart.”

The screen version of Damn Yankees premiered on September 26, 1958. Its reviews were favorable, with New York Times critic Bosley Crowther lauding Gwen Verdon as “the sort of fine, fresh talent that the screen needs badly these days” and adding that the production “has class, imagination, verve.” Variety, the show-business trade publication, described the film as “sparkling” and noted that “it does loom as a crackling musical comedy hit in the domestic markets for Warner Bros.”

All this success served to forever change the life of Douglass Wallop, the man who conjured up the saga of Joe Hardy. Now he was a celebrity, and was in demand as an after-dinner speaker at baseball banquets. When Damn Yankees was packing in audiences on Broadway, he purchased stock in the Washington Senators, explaining that he had wanted to do so for the longest time. Ever the optimist, he declared in a February 1956 interview that he had not yet earned “all the privileges of being a stockholder yet, but I hope it entitles me to buy tickets to this year’s opening game (against the Yankees) and to World Series tickets when Washington wins the pennant—maybe in 1958.” Wallop was in a more reflective mood on the first anniversary of the show’s Broadway run when he admitted that, almost immediately after handing The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant in to his publisher, he decided that penning it was a blunder. For after all, he wanted to be a serious writer. He desired to explore issues, examine the human condition. To his way of thinking, The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant was a fantasy, a trifle. How could a book about baseball be in any way significant?

Furthermore, he felt he was succumbing to the lure of fame. “It wasn’t long before my wife began to suspect that I, too, had sold my own soul to Applegate,” he noted. “The fact is, I, too, began to think that I was hearing Applegate’s voice. ‘In a couple of weeks or so,’ he’d say, ‘you can go back to the life of a writer, but it’s such a humdrum, boring life that I personally don’t see how you can stand it.’” Wallop also ruminated on the price of fame. Even though he was determined to author a “serious book,” “people asked, when are you going to write another book like ‘The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant?’ Write a book that will make another musical. Write a funny book. Be funny.”

Wallop never again was “funny.” None of his other books were transformed into Broadway shows, let alone hit ones. But in the parlance of the theater, Damn Yankees certainly had legs. Scant weeks after it closed on Broadway, Casey Stengel and Fred Haney, the respective managers of the New York Yankees and Milwaukee Braves, were each offered $1,000 per week to appear in Damn Yankees in a Las Vegas nightclub. The skippers, who had just squared off in the 1957 World Series, both politely refused.

Across the decades, the show frequently has been revived on college campuses and in community and dinner theaters, and in venues from Melbourne, Australia, to Schenectady, New York. In 1967, NBC broadcast a made-for-TV version starring Phil Silvers as Applegate and Lee Remick as Lola, with Joe Garagiola appearing as himself. In 1981, Joe Namath played Joe Hardy at the Jones Beach Theatre in New York’s Nassau County. Five years later, 99-year-old George Abbott—who lived to the age of 107—directed a revival at the Paper Mill Playhouse in Millburn, New Jersey, that featured Orson Bean as Applegate.

A version that began life at San Diego’s Old Globe Theatre, toplining Bebe Neuwirth as Lola and Victor Garber as Applegate, opened at Broadway’s Marquis Theatre on March 3, 1994. The show’s creative talent worked in conjunction with Abbott, who was present at some of the rehearsals. This version ran on the Great White Way for 718 performances, closing on August 6, 1995. Before the final curtain went down, Jerry Lewis took over as Applegate. He went on the play the part in venues from Washington’s Kennedy Center to San Francisco’s Golden Gate Theatre to London’s Adelphi Theatre.

In 2002, Dan Duquette was fired as general manager of the Boston Red Sox. A year later, he resurfaced in a Pittsfield, Massachusetts, production of Damn Yankees, playing Benny van Buren. The show was presented in the town’s minor-league ballyard, 1 1-year-old Wahconah Park. In 2005, Washington’s Arena Stage revived the show. “With the Nationals as a new neighbor, the theater has a perfect excuse for a baseball musical,” wrote Peter Marks in the Washing- ton Post. He added that, for “transparent reasons,” an “actor playing a stadium vendor sells both Senators pennants and Nationals programs”—even though the setting is the 1950s. Another version, presented at the North Shore Music Theatre in Beverly, Massachusetts, in 2006, substituted the Boston Red Sox for the Senators. Then in 2007, the show was further reworked in a version mounted in Los Angeles and directed by Jason Alexander. Here, the story was updated to 1981, and the Los Angeles Dodgers replaced the Nats as the team forever thwarted by those damn Yankees. And in 2008, the show enjoyed a brief summer run at New York City Center with Sean Hayes and Jane Krakowski starring as Applegate and Lola.

In 1964, W. W. Norton published a second edition of The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant. Most recently, the book was reprinted in 2004, with an introduction by Bill James. A year earlier, Harvey Weinstein, then co-chairman of Miramax Films, announced plans to remake Damn Yankees and film the 1970s Broadway hit Pippin. “Now, with Damn Yankees and Pippin, the ghost of Arthur Freed [the famed lyricist and legendary producer of musicals at Metro- Goldwyn-Mayer] is alive at Miramax,” Weinstein pronounced. Neither project ever made it to celluloid.

The saga of Joe Hardy has enjoyed great success in its various forms, and it may be a Washington Senators fan’s fantasy-come-true. But of course, it is fiction, pure and unadulterated. In 1955, as Damn Yankees lit up Broadway, the ballclub from the Bronx made it to the real Fall Classic—yet again. Even though they lost to the Brooklyn Dodgers, it was little solace to Senators supporters. That season, the Washington club came in dead last in the American League, winning 53 and losing 101.

In 1956—57, Chuck Stobbs, a Senators pitcher, lost sixteen straight games before notching a victory. He ended the 1957 campaign with an 8—20 record, and his team again held up the AL rear. As a rejoinder to Benny van Buren’s counsel to his players that they “gotta have heart,” Cookie Lavagetto, who replaced Chuck Dressen in May as the Nats skipper, moaned, “Believe me, brother, you gotta have a sense of humor.”

It was around this time that Harmon Killebrew often found himself compared to Joe Hardy. At one point, when “the Killer” was slumping, Washington sportswriter Bob Addie kidded the ballplayer by asking him, “What happened to Joe Hardy?” Then he noted, “Now you’re starting to hit like Andy Hardy.”

In 1958, the year Douglass Wallop’s Yankees lost the pennant, the real Bronx Bombers won the AL flag and bested the Milwaukee Braves in the World Series. And what of the Senators? Predictably, they finished the campaign at 61—93—in the American League cellar.

Sources

Books

Edelman, Rob. Great Baseball Films. New York: Citadel Press, 1994. Thorn, John, Pete Palmer, Michael Gershman, and David Pietrusza.

Total Baseball. 5th ed. New York: Viking Penguin, 1997.

Wallop, Douglass. The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant. New York: Norton, 1954.

Damn Yankees: Original Stage Production

Forty-sixth Street Theatre, New York City, May 5, 1955—May 4, 1957

Adelphi Theatre, New York City, May 6, 1957—October 12, 1957

Producers: Frederick Brisson, Robert E. Griffith, Harold S. Prince, in association with Albert B. Taylor. Director: George Abbott. Music and Lyrics: Richard Adler, Jerry Ross. Book: George Abbott, Douglass Wallop, from Wallop’s novel The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant. Musical Director: Hal Hastings. Music Orchestration: Don Walker. Dance Arranger: Roger Adams. Dances and Musical Numbers Staged by: Bob Fosse. Scenic Designers/Costume Designers: William and Jean Eckart. Sound Designer: Harry Green. Primary Opening Night Cast: Stephen Douglass (Joe Hardy); Gwen Verdon (Lola); Ray Walston (Applegate); Rae Allen (Gloria Thorpe); Richard Bishop (Welch); Shannon Bolin (Meg Boyd); Russ Brown (Van Buren); Nathaniel Frey (Smokey); Del Horstmann (Lynch, Commissioner); Elizabeth Howell (Doris); Janie Janvier (Miss Weston); Jimmie Komack (Rocky); Al Lanti (Henry); Albert Linville (Vernon, Postmaster); Eddie Phillips (Sohovik, Dancer); Robert Shafer (Joe Boyd); Jean Stapleton (Sister).

Damn Yankees: Screen Version

(1958) Warner Bros. Color. 110 minutes. Directors-Producers: George Abbott, Stanley Donen. Screenplay: George Abbott, based on the musical play Damn Yankees, book by Abbott, Douglass Wallop (from Wallop’s novel The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant ). Music and Lyrics: Richard Adler, Jerry Ross. Cinematographer: Harold Lipstein. Production/Costume Design: William and Jean Eckart. Art Director: Stanley Fleis- cher. Film Editor: Frank Bracht. Sound: Stanley Jones, Dolph Thomas. Set Decorator: John P. Austin. Makeup Supervisor: Gordon Bau. Choreography: Bob Fosse. Music Supervisor: Ray Heindorf. Associate Producers: Frederick Brisson, Robert Griffith, Harold Prince. Principal Cast: Tab Hunter (Joe Hardy); Gwen Verdon (Lola); Ray Walston (Mr. Applegate); Russ Brown (Benny Van Buren); Shannon Bolin (Meg Boyd); Nathaniel Frey (Smokey); Jimmie Komack (Rocky); Rae Allen (Gloria Thorpe); Robert Shafer (Joe Boyd); Jean Stapleton (Sister Miller); Albert Linville (Vernon); Bob Fosse (Mambo Dancer); Elizabeth Howell (Doris Miller); William Fawcett (Postmaster Hawkins)

Periodicals

Barcella, Ernest L. “Life and Hope in Baseball’s Cellar.” New York Times, 22 September 1957.

Barnes, Bart. “‘Damn Yankees’ Novelist Douglass Wallop, 64.”

Washington Post, 4 April 1985.

Berman, Rob. “A Lot of Brains, a Lot of Talent.” Playbill, 11 July 2008.

Byrne, Terry. “Diamond in the Round; Musical ‘Damn Yankees’ Gets an Update for Red Sox Crowd.” Boston Herald, 24 April 2006.

Calta, Louis. “‘Damn Yankees’ at Bat Tonight.” New York Times, 5 May 1955.

———. “‘Ice Review’ Opens Its Run Tonight.” New York Times, 13 January 1955.

———. “Play Is Planned by Nancy Davids.” New York Times, 4 January 1955.

Chapman, John. “‘Damn Yankees’ a Championship Musical and Gwen Verdon’s a Doll.” New York Daily News, 6 May 1955.

Crowther, Bosley. “Screen: Damn Yankees.” New York Times, 27 September 1958.

Daley, Arthur. “”Sports of the Times’: Overheard at the Stadium.”

New York Times, 14 September 1955.

———. “’Sports of the Times:’ The Killer.” New York Times, 20 March 1960. Funke, Lewis. “Rialto Gossip.” New York Times, 17 April 1955.

———. “Theatre: The Devil Tempts a Slugger.” New York Times, 6 May 1955. Garaventa, Joseph. “The Senators’ Triumphant Comeback.” Washington Post,

16 December 2005.

Gelb, Arthur. “Thurber Stories on Stage Tonight.” New York Times, 7 March 1955. Heller, Dick. “Play Ball Once More; Arena Presents a Revival of ‘Damn Yankees.’”

Washington Times, 20 November 2005.

Hodges, Russ. “Sounding Off with Russ Hodges.” The Sporting News, 8 June 1955.

Judge, Mark Gauvreau. “’Backtalk’: Washington Baseball Is Not for the Birds.” New York Times, 22 August 2005.

Marks, Peter. “‘Damn Yankees,’ Batting Solidly in the Mid-Fifties.”

Washington Post, 19 December 2005.

Millstein, Gilbert. “A Devil of a Game.” New York Times, 12 September 1954. Poore, Charles. “Books of the Times.” New York Times, 9 September 1954. Povich, Shirley. “‘Damn Yankees’ Stirs Nat Fans to Cheers Instead of Chuckles.”

The Sporting News, 25 May 1955.

———. “Chuck Trying Conga Contingent in Effort to Quicken Nats’ Step.”

The Sporting News, 1 June 1955.

Rohter, Larry. “Theater: At 106, George Abbott Is Still Batting for ‘Damn Yankees.’” New York Times, 27 February 1994.

“Ron,” “Damn Yankees.” Variety, 17 September 1958.

Ruhl, Oscar. “From the Ruhl Book.” The Sporting News, 8 June 1955.

———. “From the Ruhl Book.” The Sporting News, 27 November 1957. Schumach, Murray. “Devil Damns Yankees.” New York Times, 1 May 1955. Wallop, Douglass. “Perils of a Successful Musical Writer.” New York Times,

13 May 1956.

Yardley, Jonathan. “A Deal with the Devil That Still Pays Dividends.”

Washington Post, 11 August 2005.

Zolotow, Sam. “Denham Is Named to Direct ‘Seed.’” New York Times, 28 September 1954.

———. “Inge’s ‘Bus Stop’ to Open Tonight.” New York Times, 2 March 1955.

———. “Theatre Wing’s ‘Tony’ Awards Presented at Dinner Here.”

New York Times, 2 April 1956. “Books—Authors.” New York Times, 5 June 1954.

“John Douglass Wallop Dies; Author of Novel on Yankees.” New York Times, 5 April 1985.

“Nats Acquire New ‘Wallop.’” The Sporting News, 15 February 1956. “The Nation.” New York Times, 19 September 1954.

“The Rialto Gossip.” New York Times, 3 October 1954.

“Turley Learns He’s DamYankee.” The Sporting News, 1 December 1954. “Tuning In: ‘Damn Yankees’ Lose on Field.” The Sporting News, 31 August 1955.

Internet

Internet Broadway Database: http://www.ibdb.com/index.php

Internet Movie Database: http://www.imdb.com/