Democracy at the Ballpark: Looking Towards a Fan-Owned Future

This article was written by Stephen R. Keeney

This article was published in The National Pastime: The Future According to Baseball (2021)

Think about your favorite baseball team. Think about the many times a sports team you root for made a baffling decision. Think about the roster rebuild that never seems to end. Now imagine something new. Imagine buying a membership in your favorite team. Imagine voting on who runs the team or on how to finance stadium upgrades. Maybe you should even run for election to the board of directors. You would go to the ballpark knowing that every dollar you spent would go back into the team. Imagine how much better every hot dog and every beer will taste! “Get another round, we need a new shortstop!” you tell your friends, while you ponder that day’s scoreboard stumper.

This may seem like a fantasy, but it could be the future of baseball. Fan-ownership of sports teams works. The fan-owned Green Bay Packers are one of the most prestigious teams in the National Football League. In Europe, fan-owned teams dominate the top soccer competition. Moving Major League Baseball teams to a fan ownership model can lead not only to success on the field, but increased democracy, increased transparency, and a stronger sense of community and investment for fans.

Green Bay Packers fans, sporting cheese-wedge hats, one of which reads “OWNER.” (Photo by Mike Morbeck/Creative Commons)

WHY FAN OWNERSHIP?

Currently, when franchise decisions are made, there is no community involvement. Decisions are made by wealthy owners. And the interests of the fans and the interests of the owner are not always the same. This has many wondering if we need owners at all.1 As one writer put it, “Our sports franchises are public assets that we have allowed to be owned by private rich people.”2

Fan ownership means that fans control the goals, finances, and on-field product. If fans decide to pay profits back to members, then that’s up to the fans. If the fans decide that the profit margin is too big, they can make games more affordable for the average fan; this happens in Germany, whose fan-owned soccer teams generally have lower ticket prices and higher attendance than other countries.3 They can also decide to increase prices and how to spend the profits: in making the team better on the field and/or improving their communities with scholarships, grants, or other charitable or developmental enterprises. MLB teams currently do offer various forms of community support and charitable giving, but with fan ownership these become meaningful decisions made by the community.

THE STAKEHOLDERS

The ownership structures of sports franchises should be centered on the interests of all stakeholders. In the current structure, owners are the only stakeholders with any meaningful input. That interest is primarly a business one: turning a profit.

The most important stakeholders in professional sports are the fans. While the players make sports possible, fans make sports profitable. A franchise’s fans are customers, advertising audience, neighbors, community, and soul. Sports without fans are just exercise.

Another crucial stakeholder is the local community. Businesses around the stadium often rely on gameday revenue, but other businesses and organizations struggle to compete with sports. A stadium without sufficient parking can cause businesses to lose foot traffic from parking congestion during games. Fans are usually local citizens who get a sense of belonging and identity from following the local franchise, celebrating successes and mourning losses as a group. Local governments benefit from tax revenue from the stadium and players’ income, but they are also often strongarmed into giving taxpayer-funded stadiums to billionaire owners. Taxpayer funding means that even non-fans in the local community have an interest in how a franchise is run and how the local government interacts with it.

Players also have an interest in franchise decisions. They train their whole lives for a very short career. Therefore, players need to make as much money and win as much as possible in just a few years. Players have the same interest in the franchise as other workers: They create the business’s value, so they deserve a say in decision-making.

FAN OWNERSHIP MODELS

Current models give us insight into how future fanowned teams might look. There are two dominant models. The most common model looks similar to a corporation, where fans purchase some sort of buy-in that gives them voting rights. Some models give fans more to vote on, but the basic structure is that fans purchase voting rights via stock shares or membership fees, and then vote for directors who oversee franchise operations. Less common is direct, municipal ownership by the local government. In the second model, fans get voting rights from citizenship.

The most famous example of the corporate model in American sports is the Green Bay Packers. Packers fans buy in when new “shares” are issued. Shares give them the right to vote for team directors, who then elect a committee to make the operational decisions by hiring a GM, who runs the day-to-day operations. While reasonable minds can disagree on how much say this really gives fans, the fact is that most American sports fans lack even that much say in their team’s operation. In 2011 the Packers announced a plan for a $146 million stadium improvement, paid for with a new round of stock offerings instead of strong-arming the local government to use tax dollars.4

There are similar examples in affiliated baseball’s minor leagues. The Syracuse (NY) Chiefs of the International League were a fan-owned team from 1961 until 2017. They originated as a fan-owned team after multiple owners moved teams out of Syracuse. Fans bought shares which allowed them to vote for directors, with no person allowed to vote more than 500 shares, no matter how many they owned. Financial trouble hit in the 2000s, and in 2017, after a bizarre series of events, the team was sold to the New York Mets.5 The team took a loan from a group of directors in exchange for 600 shares plus control of the board.6 The group installed their own general manager, then reported about one-third of all shares (representing more than half of all shareholders) as abandoned property to the State of New York, increasing the per-share profit of the remaining shares from the sale to the Mets.7 Over 900 people had to reclaim their shares to get a share of the profits from the sale.8

Another fan-owned team that went private recently was the Wisconsin Timber Rattlers. The High-A team, along with its Fox Cities Stadium and sister team, the Fond Du Lac Dock Spiders, were owned by the Appleton Baseball Club—a fan-owned venture that operated minor-league baseball in Appleton, Wisconsin, since 1939.9 The club failed financially due to the cancellation of the 2020 season during the COVID-19 pandemic. The club was purchased by Third Base Ventures, a group headed by Craig Dickman, a long-time Appleton and Green Bay Packers director, for an undisclosed fee.

Other examples of this style of ownership are on display at the highest levels of European soccer. In Germany’s Bundesliga, all clubs must follow a 50 + 1 rule, requiring the club to hold at least 50% plus one of all of its own shares. The club is run by presidents and directors who are elected by the members—fans who pay a membership fee. This means no private owner can take control of the club away from the fans and put profits ahead of fan interests.10 The prices of membership are affordable for average fans. Membership fees for Germany’s largest and most successful club, Bayern Munich, run just 60 Euros (~$72) per year.11 The second most successful and third biggest club, Borusia Dortmund, only costs 62 Euros ($75) per year.12 Because the focus is on the fans and the team rather than profits, Germany has some of the lowest ticket prices and highest attendances in all of Europe.13

Spanish soccer also gives us examples, where the two richest and most successful clubs are fan-owned: Real Madrid and FC Barcelona. Under Spanish law, soccer clubs must be privately owned, with four clubs (Real Madrid, Barcelona, Athletic Bilbao, and CA Osasuna) being grandfathered in as fan-owned clubs.14 For these clubs, fans buy a membership, which gives them the right to vote on directors, president, and various other club items. Membership costs a Real Madrid fan about 150 Euros (~$181), and an FC Barcelona fan 185 Euros ($224).15 The membership structure ensures that these clubs cannot be purchased by private owners.

Critics of the fan-ownership models in soccer say that teams need rich, private owners to put in the money necessary to compete in Europe. This criticism fails both in regard to team success and fan happiness. In Spain, Real Madrid, Barcelona, and Athletic Bilbao have combined to win 68 of 89 league championships (76%).16 From 2010 through the 2020 campaign, Real Madrid, Barcelona, or Bayern Munich have won 8 of the 10 UEFA Champions League titles.17 In fact, Real Madrid, Barcelona, or a German team have won 26 of 65 tournaments (40%), with Real Madrid having the most wins ever (13), Bayern tied for third (6), and Barcelona fifth (5).18 These three teams also lead all of Europe in their UEFA Club Coefficient, a stat measuring a team’s success in European competitions over the past five years.19 This success, combined with the fact that German soccer continually has the best league-wide attendance numbers across Europe, shows that fanownership can deliver trophies, fan empowerment, and financial stability.

A less common method of fan/community ownership is the direct ownership of a team by a local government entity. The best example of this was the Double-A Harrisburg (PA) Senators. The private owners of the Senators threatened to move the team unless the city gave them a new, publicly-funded stadium. Faced with the choice between an unreasonable demand and losing their local team, the City of Harrisburg decided to buy the franchise outright in 1995. The purchase price was $6.7 million, with $1.25 million coming from capital reserves and the remaining $5.45 million coming from a bond issue.20 Facing budgetary issues, the city sold the team in 2007 for $13.25 million plus a guarantee to keep the team in Harrisburg for at least 29 years.21

The fact that Harrisburg bought their team with public money, nearly doubled their investment in just over a decade, and kept the team in town shows that municipal ownership can work. In this model, a sports team could operate much the same way as a municipal “enterprise fund,” where certain activities are paid for and run in ways similar to what a private business might do, except that public service, rather than private profit, is the driving motivation. For example, many cities or counties own their water or electricity distribution services. They provide the water or power to citizens and businesses and charge fees for distribution and usage. Often, the money paid to the water or power system is put into its own account, separate from the government’s “general fund,” but still under the control of local elected officials. That money is then used primarily to improve those services, but can also be moved to the “general fund” under certain circumstances to accomplish other government objectives.

The issue of municipal ownership has come up in the major-league baseball context as well. When McDonald’s founder and owner of the San Diego Padres Ray Kroc died in 1984, his widow Joan Kroc inherited the team. She tried to donate the team to the City of San Diego, but an owners’ committee persuaded her to drop the idea, and she sold the team in 1990.22 When Major League Baseball took control of the Dodgers from the feuding McCourts, sports journalist Dave Zirin advocated for the team to be given to the fans, while also lamenting the lack of public pressure to do so.23 These examples show the single largest obstacle to any meaningful development in fan ownership is the leagues themselves. All major American sports leagues, including Major League Baseball, now prohibit anything but private, for-profit ownership of teams.24

FAN-OWNED vs COMMUNITY-OWNED MODELS

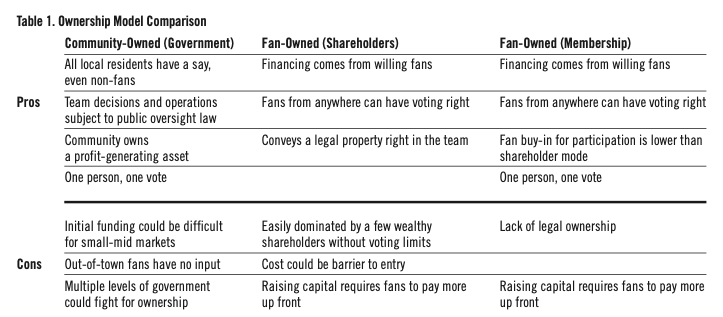

As we think about a future of fan-owned baseball teams, we have to consider what features are necessary to achieve ownership that is democratic, transparent, and representative of fan interests. To see what this looks like, consider the two dominant forms already discussed: community ownership, which would be ownership by some level of government, and fan ownership, which would be ownership by fans who buy some sort of voting rights share.

Community ownership is a straightforward concept. The city, county, or state would take over the team and appoint employees to operate it under the same laws and regulations that other government agencies have to follow. The teams could be run like other “enterprise funds,” such as municipal power, water, or other services with their own budgets and oversight.

The government entity could purchase the team the way Harrisburg did when it bought the Senators, or it could forcibly purchase the team from the current owners with Eminent Domain. Eminent Domain is the legal principle stemming from the Fifth Amendment of the US Constitution, which provides that the government can take private property as long as the owner receives due process and fair market value in return, and the property will be for public use. Usually in sports, property is taken from low-income residents and given to wealthy owners on the premise that having the team is a public purpose, even if the taken property becomes private.25 In this case, the taking would turn the business into public property.

This form of ownership has several advantages. First, the decisions, finances, and inner workings of the team would be required to comply with the principles of democracy, community input, and transparency (sunshine laws, open meetings laws, etc.) that governments are subject to under state, federal, and local law. This is a benefit to all in the community who currently have no say and little access to information about team operations. Second, this method puts all community members on equal footing, regardless of fanhood. Finally, the community would own a profitgenerating asset whose proceeds are used to benefit the citizens. Cities could decide to keep profits low by keeping ticket prices low, which is good for the fans, or it could decide to use the profits for public services. Imagine profits from beer and hot dogs at the ballpark being used to fix roads, hire more firefighters, or provide better public education.

There are cons to this method of ownership. Not all fans live within the city, county, or state where their team sits. My hometown Cincinnati Reds, a small-market team, have fans not only in Cincinnati, but in other counties in Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana. Those fans would be left out of any say in or benefit from a community ownership model. Another issue is deciding which level or levels of government should own the team. While cities like Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, can afford to buy a Double-A team, how many large cities can afford to buy a major-league team? Surely cities like New York, Los Angeles, or Chicago could find the money. But cities like Cincinnati, Cleveland, Kansas City, or Milwaukee may not have the money or operational capacity. With smaller cities, the county’s or state’s help might be needed. However, as one author pointed out several years ago, sometimes cities spend more on stadiums to give to teams than it would cost to buy the team outright.

Fan ownership using a Board of Directors is another approach. In this case, the teams would have to be bought by—or given to—the new entity from the previous owner. We have seen examples of shareholder and membership models. A shareholder model like that in Green Bay and most other American examples is a step in the right direction, but the membership model holds more promise as a way to allow more fans to participate and to prevent private owners from taking the club back.

As we saw with the Syracuse Chiefs, allowing individuals to buy more shares gives those individuals more voting power. That is how a few directors with outsized voting rights privatized a fan-owned team. When the vote to approve the sale to the Mets took place, about 100 of the approximately 4,000 shareholders voted, but almost two-thirds of the shares were voted. Some methods to limit this power by wealthy individuals would be to make the shares unable to be cashed out, as the Green Bay Packers have done, or to have a Board of Directors made up of a minority of shareholders, with the other seats on the Board held by local government representatives and player representatives. An absolute limit on the number of shares that any one person or entity can vote is essential for this type of ownership to be any different from current ownership.

By contrast, the membership method with a one-member-one-vote setup allows far more people to participate in the decision-making, and prevents a few individuals from wielding outsized influence. This prevents individual members from being “owners” in a legal sense, which means that there is no incentive for them to seek profit from membership. As we saw with the European soccer examples, a reasonably priced membership can be affordable for the average fan where stock shares might not be. A membership system also breeds participation because once someone stops being a member, their voting rights cease. Votes will not be tied up by people whose parents bought stock and lost the certificate in the attic decades ago, as was the case in Syracuse. Since there is no vested property interest there is nothing to sell, transfer, bequeath, or inherit, except maybe season tickets. For those reasons, a membership model is better than a shareholder model for increasing fan participation and ensuring democratic control by the most important stakeholders.

In any ownership model, it would be a mistake to shut out the players or the local government from decision-making. In either fan-owned model, a set number of director seats should be reserved for members/shareholders, a set number for the local community, and a set number for players. The players are the ones who make sports what they are. They deserve a voice in how each team is run.

Table 1. Ownership Model Comparison

(Click image to enlarge)

HOW TO GET THERE FROM HERE

The road to any sort of fan-ownership model for Major League Baseball will likely be long, winding, and fraught with danger for municipalities brave enough to take on billionaire owners. The first hurdle is the current owners. An owner giving a team away to a community or a fan group would be simple enough, at least in theory. Fans of the English soccer team Newcastle United have started taking pledges of money from fans to buy an interest—however small—in the club if the owner sells the team.27 But taking a team by force would be a whole different ballgame. In theory, cities or states could use the power of eminent domain to take ownership of sports franchises. This has been tried in the past, but never succeeded for different reasons. The City of Baltimore tried to use eminent domain to take over the Colts, but a court later ruled that Bob Irsay snuck out of town just in time, and since the team was no longer there, the city could not take over the team.28 The City of Oakland also tried to use eminent domain in the 1980s to prevent the Raiders from moving out of town. Eventually, a California appeals court held that the city taking over the Raiders would violate the US Constitution’s commerce clause because it would interfere with the interests of the other league owners.29

That notion brings up the next hurdle, the leagues themselves. As previously mentioned, every major sports league in the United States prohibits non-profit ownership among its members. Additionally, because Congress has granted the leagues exemptions from antimonopoly statutes (except for Major League Baseball, whose exemption is from the Supreme Court), there is little that can be done outside of an Act of Congress to force the leagues to accept municipal or non-profit owners. In theory, Congress could again raise the specter of eliminating those protections to strong-arm the leagues into changing their rules. They have tried it before, but the law failed in the end.30 Congress could also, potentially, simply make such provisions in the league charters illegal. With the lobbying power of the leagues and their owners, this route would be a long-shot without a massive amount of popular mobilization on the part of sports fans and affected citizens across the country. We are simply not there right now.

Perhaps a foothold is all that is needed. The Packers and soccer giants Real Madrid and Barcelona show that you do not need rich, individual ownership to succeed on the field. But right now, a fan-owned or community-owned team would have a massive uphill battle just to get on the field. This creates a chicken-and-egg question for supporters of fan-ownership: will there be a chance to show that these models can work within the leagues and slowly change more teams from private to fan-owned over time, or must there be a critical mass of cities or fan groups ready to make a move at once to even get in the door?

A FAN-OWNED FUTURE

What both fan-owned models share is that decisions will more likely be made in the interests of the club. By removing the profit motive, the focus becomes the short-term and long-term health and success of the team. One con is that in both models the people who end up in charge are usually just different wealthy people. And while that may not be ideal for a truly democratic team operation, the fact that they are held accountable to the rest of the voters means they are less likely to act out of self-interest than unaccountable private owners.

None of this is to say that current owners are all bad. There are plenty of owners out there who put a good product on the field, support the local community, and are willing to pay good money for good players. But in a sports franchise, just as in any other business, the profit motive is always there. That motive can be aligned with the interests of the fans and the local community, or it could run counter to those interests.

A future with more fan-owned teams is a future with a better fan experience. Bringing more democracy to professional sports teams means more value for and more input from the most important stakeholders. The current owners will be fine. Some might give the team to the community as Joan Kroc tried to do. Some might be bought out at a profit. Others might lose the team via Eminent Domain, meaning they would be paid fair market value for the franchise, almost certainly at a profit. But unlike many fans, these former owners won’t spend season after season despairing over decisions made by people who care more about profits than the team or the community. A fan-owned future means truly being part of the team.

STEPHEN R. KEENEY is a lifelong Reds fan. He graduated from Miami University in 2010 and from Northern Kentucky University’s Chase College of Law in 2013. He lives in Dayton, Ohio, as a union staff representative with his wife and two children. He has contributed to several SABR publications, and his article “The Roster Depreciation Allowance: How Major League Baseball Teams Turn Profits into Losses” was selected for SABR 50 at 50: The Society for American Baseball Research’s Fifty Most Essential Contributions to the Game.

Notes

1. Henry Druschel, “Imagining a Fan-Owned Team,” September 27, 2017, BeyondtheBoxscore.com, https://www.beyondtheboxscore.com/2017/9/27/16367428/public-ownership-baseball-teams-socialism-universal-basic-income. Ben Burgis, “Sports Team Should be Owned by the Public,” JacobinMag.com, December 28, 2019, https://jacobinmag.com/2019/12/nfl-cowboys-jerry-jones-football-owners-public-ownership.

2. Harvey Wasserman, “The Real Solution to Scumbag Sports Owners,” CounterPunch, April 30, 2014, https://www.counterpunch.org/2014/04/30/the-real-solution-to-scumbag-sports-owners/?fbclid=IwAR2569-v52qPgY_tTliQ-ImftGEBZc8uPjZqrTfWq_C42WEoR7giR3YHnD0.

3. Raffaele Poli, Loic Ravenel, and Roger Besson. “Attendance in Football Stadia (2003-2018),” CIES Football Observatory Monthly Report No. 44, April 2019 (International Centre for Sports Studies), available at https://football-observatory.com/IMG/pdf/mr44en.pdf.

4. “Green Bay Packers Shareholders,” Green Bay Packers, accessed April 3, 2021, https://www.packers.com/community/shareholders.

5. Lindsay Kramer, “Syracuse Chiefs Shareholders Approve Sale to New York Mets,” Syracuse.com, November 17, 2017, https://www.syracuse.com/chiefs/2017/11/syracuse_chiefs_shareholders_approve_sale_to_new_york_mets.html.

6. John O’Brien, “To Escape Fiscal Crisis, Syracuse Chiefs’ Board Considers Offers: One for $500,00, Another For $1 million.” Syracuse.com, September 30, 2013, https://www.syracuse.com/news/2013/09/syracuse_chiefs_board_considering_two_investment_proposals.html.

7. Roger Cormier, “No, The New York Mets’ Acquisition of the Syracuse Chiefs Did Not Go Smoothly,” GoodFundies.com, December 17, 2017, https://goodfundies.com/no-the-new-york-mets-acquisition-of-the-syracuse-chiefs-did-not-go-smoothly-dbacbd34b5cd.

8. Ricky Moriarty, “More Than 900 Syracuse Chiefs Owners to Get Back $2 Million in ‘Abandoned’ Stock,” Syracuse.com, December 1, 2017, https://www.syracuse.com/business-news/2017/12/more_than_900_syracuse_chiefs_owners_to_get_2_million_in_abandoned_stock_back.html.

9. “Wisconsin Timber Rattlers, Fox Cities Stadium Sold,” The Business News, January 23, 2021, https://www.readthebusinessnews.com/features/merger_acquisitions/wisconsin-timber-rattlers-fox-cities-stadium-sold/article_e1756586-4fb2-11eb-ba26-ff31134e2efe.html.

10. “German Soccer Rules: 50+1 Explained,” Bundesliga.com, accessed April 3, 2021, https://www.bundesliga.com/en/news/Bundesliga/german-soccer-rules-50-1-fifty-plus-one-explained-466583.jsp.

11. “Pricing: Membership Fees,” FC Bayern, accessed April 3, 2021, https://fcbayern.com/en/club/become-member/pricing.

12. “Apply for Membership,” Borussia Dortmund, accessed April 3, 2021, https://www.bvb.de/eng/BVB/Membership/Apply-for-membership.

13. Poli, Ravenel, and Besson, “Attendance in Football Stadia.”

14. Khalid Khan, “Cure or Curse: Socio Club Ownerships in Spanish La Liga,” Bleacher Report, June 11, 2010, https://bleacherreport.com/articles/404511-cure-or-curse-socio-club-ownerships-in-spanish-la-liga.

15. “Types of Card,” Real Madrid FC, accessed April 3, 2021, https://www.realmadrid.com/en/members/member-card/types-and-prices; “Become a Member, FC Barcelona, accessed April 3, 2021, https://www.fcbarcelona.com/en/club/members/become-member/registration-of-adult-members.

16. “Spain—List of Champions,” Rec Sport Soccer Statistics Foundation, accessed April 3, 2021, http://www.rsssf.com/tabless/spanchamp.html.

17. “History,” UEFA, accessed April 3, 2021, https://www.uefa.com/uefachampionsleague/history/.

18. “History: Winners,” UEFA, accessed April 3, 2021, https://www.uefa.com/uefachampionsleague/history/winners/.

19. “UEFA Club Coefficients,” UEFA, accessed Aril 3, 2021, https://www.uefa.com/memberassociations/uefarankings/club/#/yr/2021

20. Megan O’Matz, “Harrisburg Strikes Deal for Senators, City Will Pay $6.7 Million to Keep Baseball Team,” The Morning Call, July 8, 1995, https://www.mcall.com/news/mc-xpm-1995-07-08-3055425-story.html.

21. “Harrisburg Senators Sale Announced,” MiLB.com, May 16, 2007, http://www.milb.com/gen/articles/printer_friendly/milb/press/y2007/m05/d16/c244716.jsp.

22. “Panel Blocked Bid to Give Padres to City of San Diego,” LA Times, July 30, 1990, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-07-30-sp-1027-story.html.

23. Dave Zirin, “Baseball’s Blues: It’s Not Just the Dodgers,” LA Times, April 22, 2011, https://www.latimes.com/sports/la-xpm-2011-apr-22-la-oe-zirin-dodgers-20110422-story.html.

24. The Green Bay Packers avoid this requirement because they were grandfathered in. They existed before the current rules were created, which apply only to new owners (known as “members” in the NFL Constitution, Article 3.2). The Packers were formed in 1919, the NFL (under a prior name) was formed in 1920, and the current NFL constitution dates back to 1970 when the AFL-NFL merger was completed.

25. For example, Eric Nusbaum, Stealing Home: Los Angeles, the Dodgers, and the Lives Caught in Between (New York: Hachette Book Group, 2020).

26. Neil deMause, “The Radical Case for Cities Buying Sports Teams, Not Sports Stadiums,” Vice.com, December 29, 2014, at https://www.vice.com/en/article/vvakva/the-radical-case-for-cities-buying-sports-teams-not-sports-stadiums.

27. “Newcastle United: Supporters Set Up a Fund to Buy Part of Premier League Club If Sold,” BBC.com, April 8, 2021, available at https://www.bbc.com/sport/football/56673354.

28. M. & C. Council of Baltimore v. B. Football C., 624 F. Supp. 278 (D. Md. 1986), available at https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/624/278/2305222/.

29. City of Oakland v. Oakland Raiders, 174 Cal.App.3d 414 (Ct. App. 1985), available at https://www.leagle.com/decision/1985588174calapp3d4141559.

30. Neil deMause, “The Radical Case for Cities Buying Sports Teams, Not Sports Stadiums,” Vice.com, December 29, 2014, at https://www.vice.com/en/article/vvakva/the-radical-case-for-cities-buying-sports-teams-not-sports-stadiums.