Eddie Waitkus and “The Natural”: What is Assumption? What is Fact?

This article was written by Rob Edelman

This article was published in The National Pastime: From Swampoodle to South Philly (Philadelphia, 2013)

Eddie Waitkus, the Fightin’ Phillies first-sacker, is best remembered not for his 182 hits and .284 average on the 1950 National League pennant-winners and not for any other on-field accomplishment. Instead, his name is inexorably linked to the plight and fate of the central character in an all-time classic baseball novel.

One might imagine that The Natural—written by Bernard Malamud and published in 1952—is unadulterated fiction, while the 1984 screen adaptation is a baseball fantasy with a literary origin. However, a question that has long intrigued aficionados and scholars involves how much of Malamud’s story has been culled from real life. To what extent was he influenced by baseball history and baseball lore? Even more specifically, what was Malamud’s inspiration for one of the novel’s crucial episodes: the near-fatal shooting in a Chicago hotel room of Roy Hobbs, the story’s principal character, by a black-garbed mystery woman? Was it in fact a direct reference to the blast from a rifle wielded by an overwrought fan which almost snuffed out the life of Waitkus, also in a Chicago hotel room, on the night of June 14, 1949?

Malamud (1914–86) was loath to discuss his literary sources. As reported in an editor’s note in Talking Horse: Bernard Malamud on Life and Work, “…during his lifetime as an artist and writer, [Malamud] said little in private about his own work. In public he said even less.” So determining the genesis of the Hobbs shooting, not to mention other actual baseball influences in The Natural, is purely speculative, the equivalent of piecing together a giant puzzle that keeps changing shape.

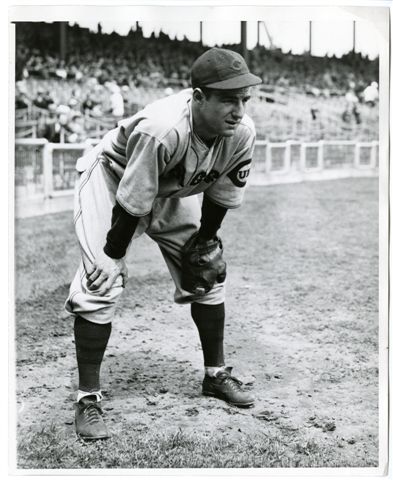

In relation to the real-life Eddie Waitkus and the fictional Roy Hobbs, the two on the surface have little in common. Edward Stephen Waitkus was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on September 4, 1919. After debuting with the Chicago Cubs in 1941, he earned four Bronze Stars while serving with the U.S. Army in the Pacific during World War II. He returned to the Cubs in 1946 and, with Hank Borowy, was traded to the Phillies for Dutch Leonard and Monk Dubiel after the 1948 campaign. “During his early career,” explained Waitkus biographer John Theodore in A Natural Gunned Down: The Stalking of Eddie Waitkus, a documentary extra found on the Director’s Cut DVD release of the movie version of the novel, “[Eddie] was called ‘The Natural’ by a few sportswriters. The writers back then also called him the ‘Fred Astaire of first basemen.’ At the plate, he had a wonderfully natural swing. Ted Williams called it one of the best swings he had ever seen.” Off the field, according to Theodore, Waitkus “was very urbane. He spoke four languages. He was a Civil War historian. He loved ballroom dancing. [He was] not your typical blue-collar baseball player.”

In relation to the real-life Eddie Waitkus and the fictional Roy Hobbs, the two on the surface have little in common. Edward Stephen Waitkus was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on September 4, 1919. After debuting with the Chicago Cubs in 1941, he earned four Bronze Stars while serving with the U.S. Army in the Pacific during World War II. He returned to the Cubs in 1946 and, with Hank Borowy, was traded to the Phillies for Dutch Leonard and Monk Dubiel after the 1948 campaign. “During his early career,” explained Waitkus biographer John Theodore in A Natural Gunned Down: The Stalking of Eddie Waitkus, a documentary extra found on the Director’s Cut DVD release of the movie version of the novel, “[Eddie] was called ‘The Natural’ by a few sportswriters. The writers back then also called him the ‘Fred Astaire of first basemen.’ At the plate, he had a wonderfully natural swing. Ted Williams called it one of the best swings he had ever seen.” Off the field, according to Theodore, Waitkus “was very urbane. He spoke four languages. He was a Civil War historian. He loved ballroom dancing. [He was] not your typical blue-collar baseball player.”

A two-time National League All-Star (in 1948–49), the 29-year-old Waitkus was hitting .306 when he was shot on June 14, 1949; his assailant, Ruth Ann Steinhagen, a stenographer, was a decade his junior. He did not don a Phillies uniform for the remainder of the 1949 season. However, on August 19, the ballclub sponsored “Eddie Waitkus Night,” during which the ballplayer was deluged with gifts. He rejoined the team the following season, playing in all 154 games for the World Series-bound Whiz Kids—and the Associated Press cited him as the Comeback Player of the Year. Prior to the 1954 campaign, the Baltimore Orioles purchased him. He was released by the Orioles during the 1955 season and returned to Philadelphia before retiring at year’s end. All in all, Waitkus enjoyed an eleven-year big league career, hitting .285 with 1,214 hits.

Hobbs, meanwhile, is neither big-city sophisticate, weathered war veteran, nor veteran major leaguer. He is a true innocent: a 19-year-old hot prospect, a product of rural America, and a pitcher with untold potential. Harriet Bird, the woman in black, is older than Steinhagen, and she exploits Hobbs’s youthful ardor before shooting him and then committing suicide. Her motives—and whether she indeed is acting on her own or is in cahoots with others—remain unclear. But Hobbs’s career is sidetracked, and he spends the next decade and a half languishing in obscurity with his promise an unfulfilled dream. Then, as a middle-aged rookie, he returns to baseball as a hitter and leads the last-place New York Knights up in the standings. Hobbs rises from the ashes when he is 34: an age when Waitkus was inauspiciously winding down his big league career. And there was nothing mysterious about Steinhagen. When she shot and wounded the unmarried big leaguer in room 1297A of Chicago’s Edgewater Beach Hotel, the Phillies were in town to play the Cubs—and Steinhagen had been obsessed with Waitkus for several years, dating from his time in Chicago. According to John Theodore, the 19-year-old had constructed a shrine to the ballplayer, consisting of hundreds of photos and clippings, which she would stare at for hours. Her mother reported that she even would set a place for him at the family dinner table. After his trade to the Phillies, she felt abandoned—and her infatuation became deadly.

The story of Steinhagen was extensively covered in the media. As reported in several accounts published in The New York Times and elsewhere, a note from the teenager awaited Waitkus’s arrival at the hotel that evening. It was signed “Ruth Anne Burns” and, in it, Steinhagen wrote:

It is extremely important that I see you as soon as possible. We’re not acquainted, but I have something of importance to speak to you about. I think it would be to your advantage to let me explain this to you as I am leaving the hotel the day after tomorrow. I realize this is out of the ordinary, but as I say, it is extremely important.

Steinhagen originally was planning to stab Waitkus and then shoot herself. Accounts vary as to what exactly happened when Waitkus entered her room. But what is clear is that, in an instant, Steinhagen changed her plans and shot the ballplayer but lost her nerve and failed to harm herself.

After the incident, Waitkus told reporters, “I went up to my room and called her because I thought it might be someone I knew—someone from downstate or a friend of a friend. When she opened the door, she took a look and said, ‘come in for a minute.’ She was very abrupt and businesslike. I asked what she wanted and walked through the little entrance hall over to the window. When I turned around there she was with the .22 caliber rifle. She said, ‘You’re not going to bother me anymore.’ Before I could say anything else, whammy!” He added, “She had the coldest looking face I ever saw. No expression at all. She wasn’t happy—she wasn’t anything.” Waitkus noted that he had never met Steinhagen, and was unsure if he ever had received correspondence from her. “We ballplayers get a lot of letters from girls and don’t pay any attention to them. We call them ‘baseball Annies.’”

Waitkus was rushed to Illinois Masonic Hospital, where he was reported to be in critical condition with a rifle slug lodged in muscles near his spine. The bullet first pierced and collapsed his right lung, and he received two blood transfusions as well as oxygen. The bullet was surgically removed and, on June 18, another operation was performed to remove blood from his lung cavity. All in all, Waitkus underwent four procedures, and doctors described his quick improvement as “little short of miraculous.” The ballplayer also told reporters, “I haven’t got over the whole surprise. It’s just like a bad dream. I would just like to know what got into that silly honey picking on a nice guy like me. She must be crazy, charging around with a rifle. It was safer for me on New Guinea, wasn’t it?”

For her part, Steinhagen was booked by the police and charged with “assault with intent to murder.” She told the authorities that she “just had to shoot somebody,” adding that she liked Waitkus “best of anybody in the world” and had been dreaming about him—and praying for him. According to the Times, the police “attributed Miss Steinhagen’s action to a twisted fascination for the ball player and a desire to be in the limelight.” She was committed to Illinois’ Kankakee State Hospital, where she was given shock treatments. Steinhagen never went on trial for shooting Waitkus. Instead, she remained at Kankakee until 1952, when she was declared cured and released. She then faded into obscurity, and resided for decades in Chicago. In March 2013, the Chicago Tribune reported that she had died in Chicago three months earlier at age 83, after a fall in her home.

While Waitkus, unlike Hobbs, did not have to wait a decade and a half to resume his baseball career, one can only speculate on the overall impact of the shooting on the quality of his play. Sure, he was one of the stars of the 1950 Whiz Kids, but would he have enjoyed additional all-star seasons with the Phillies? What numbers might he have put up? Might he even have been worthy of consideration for the Baseball Hall of Fame? We will never know. However, the shooting clearly affected the ballplayer’s private life. For one thing, in the late 1980s, New York Times sports columnist Ira Berkow heard from Waitkus’s son, Edward (Ted) Waitkus Jr., a Boulder, Colorado, lawyer. The junior Waitkus reported that his father had met his mother while recovering from the shooting in Clearwater Beach, Florida. “Had it not been for this horrible event in his life, my sister and I would probably not be here,” he noted. “Life is very ironic. I think sometimes that all horror that comes to us has reason….”

Given that The Natural was published in 1952, Bernard Malamud could not have known what the future would hold for Eddie Waitkus. Yet certain aspects of Waitkus’s later life did indeed reflect on the plight of Roy Hobbs as envisioned by the writer. According to Ted Waitkus, his father “had always told me he understood the four years of his career lost to World War II. ‘Everyone went,’ he would say. He, however, never quite accepted being shot, that is, the time lost because of the shooting.” He also noted, “My dad was an easy-going, trusting guy at the time, and kind of flippant with women…. The shooting changed my father a great deal, as you might imagine. Before, he was a very outgoing person. Then he became almost paranoid about meeting new people, and pretty much even stopped going out drinking with his teammates, which is what I guess they did in those days.” And he added, “When [Steinhagen] was about to be released from the mental hospital after only a few years—they said she had fully recovered—my father and my family fought to keep her in. My father feared for his life.”

After his retirement from baseball, Waitkus faded from the limelight. In 1961 he split from his wife and suffered a nervous breakdown. “In my research talking to doctors,” reported John Theodore, “they concluded that he was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder because his symptoms were classic. He avoided people. He had anxiety. He self-medicated his depression with alcohol.” A partial return to baseball came in 1966, when he hired on as a hitting instructor at Ted Williams’s baseball camp. However, in 1972, at the all-too-young age of 53, Waitkus died of esophageal cancer. At the time, he was living in a Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, boardinghouse. “Different doctors through the years have expressed the theory that the stress of the shooting, combined with the four operations, allowed the cancer to take hold,” explained Ted Waitkus. “Cancer of the lung or esophagus can take up to 20 years or more to be fatal. My dad was never diagnosed as having cancer. It wasn’t until after the autopsy that this came out. So I think Ruth Steinhagen was more successful than she thought.”

***

Conjecture regarding the connection between fiction and reality in The Natural dates from its publication. In his review of the book in the August 24, 1952, New York Times, Harry Sylvester observed that Malamud “draws heavily on baseball legend and history, almost interchangeably.” Since then, writers, reviewers, and historians have speculated about the players, personalities, and events that may (or may not) have influenced Malamud during the writing process.

Countless observers have assumed—and casually reported—that the entire premise of The Natural is directly linked to the Waitkus shooting. Here are some representative examples:

- “The shooting of Eddie Waitkus inspired Bernard Malamud to write The Natural, first published in 1952.” (Charles DeMotte, in “Baseball Heroes and Femme Fatales,” The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture: 2002)

- “What happened to Waitkus provided the inspiration for Bernard Malamud’s The Natural.” (Wil A. Linkugel and Edward J. Pappas, They Tasted Glory: Among the Missing at the Baseball Hall of Fame)

- “The incident inspired Bernard Malamud to write his 1952 novel The Natural.” (Joshua Prager, The Echoing Green: The Untold Story of Bobby Thomson, Ralph Branca and the Shot Heard Round the World)

- “…the attack [on Waitkus] was the seed from which Malamud’s story had grown.” (G. Richard McKelvey, Lost in the Sun: The Comebacks and Comedowns of Major League Ballplayers)

- “[Waitkus’] story was the inspiration for the Roy Hobbs character in Bernard Malamud’s The Natural.” (Steve Johnson, Chicago Cubs Yesterday & Today)

- “[The Waitkus case] inspired Bernard Malamud to write The Natural…” (Gordon Edes, writing in the South Florida Sun Sentinel)

- “[The book was] inspired by the 1949 shooting of Philadelphia Phillies first baseman Eddie Waitkus…” (Carolyn Kellogg, writing in the Los Angeles Times)

- “[The Waitkus shooting] inspired Bernard Malamud to write his 1952 classic novel, The Natural.” (Bob Minzesheimer, writing in USA Today)

- “[The book’s] immediate inspiration was the real-life case of one Eddie Waitkus, a first baseman for the Philadelphia Phillies who was also shot by a deranged woman in a hotel room.” (Kevin Baker, in the introduction to a 2003 reprint of The Natural)

Nonetheless, it is flat-out incorrect to declare that the murder attempt on Eddie Waitkus was the singular inspiration for The Natural. For one thing, might the shooting of Roy Hobbs have been an outgrowth of an altogether different incident: the July 1932 shooting of Chicago Cubs shortstop Billy Jurges by Violet Valli, a showgirl with whom he was romantically connected? To expand this further, might Malamud have been aware of a certain piece supposedly penned by New York Times columnist Arthur Daley—the existence of which has taken on a life of its own? In the novel (as opposed to the screen adaptation), Roy Hobbs’s ego allows him to be fatally corrupted—and it is noted in “A Talk With B. Malamud,” published in the Times in 1961, that The Natural “was suggested by a column written by Arthur Daley for this newspaper—why does a talented man sell out?” Even though there are no direct quotations from Malamud in this piece, in After Alienation: American Novels in Mid-Century, published in 1964, Marcus Klein reported that the book “was suggested, Malamud has said, by one of Arthur Daley’s columns in The New York Times, which raised the question, why does a talented man sell out?” In a Daley obituary published in Dictionary of American Biography, Kevin J. O’Keefe noted that “one of Arthur Daley’s columns concerned a talented baseball player’s betrayal of his principles and was turned into a book, The Natural, by Bernard Malamud.” In a paper titled “Daley’s Diamond: The Baseball Writing of Arthur J. Daley,” Jim Harper observed, “Daley’s treatment of gambling and fixing in sport inspired novelist Bernard Malamud to explore the theme of a talented athlete gone wrong in The Natural.”

Nonetheless, it is flat-out incorrect to declare that the murder attempt on Eddie Waitkus was the singular inspiration for The Natural. For one thing, might the shooting of Roy Hobbs have been an outgrowth of an altogether different incident: the July 1932 shooting of Chicago Cubs shortstop Billy Jurges by Violet Valli, a showgirl with whom he was romantically connected? To expand this further, might Malamud have been aware of a certain piece supposedly penned by New York Times columnist Arthur Daley—the existence of which has taken on a life of its own? In the novel (as opposed to the screen adaptation), Roy Hobbs’s ego allows him to be fatally corrupted—and it is noted in “A Talk With B. Malamud,” published in the Times in 1961, that The Natural “was suggested by a column written by Arthur Daley for this newspaper—why does a talented man sell out?” Even though there are no direct quotations from Malamud in this piece, in After Alienation: American Novels in Mid-Century, published in 1964, Marcus Klein reported that the book “was suggested, Malamud has said, by one of Arthur Daley’s columns in The New York Times, which raised the question, why does a talented man sell out?” In a Daley obituary published in Dictionary of American Biography, Kevin J. O’Keefe noted that “one of Arthur Daley’s columns concerned a talented baseball player’s betrayal of his principles and was turned into a book, The Natural, by Bernard Malamud.” In a paper titled “Daley’s Diamond: The Baseball Writing of Arthur J. Daley,” Jim Harper observed, “Daley’s treatment of gambling and fixing in sport inspired novelist Bernard Malamud to explore the theme of a talented athlete gone wrong in The Natural.”

On the rare occasion in which he discussed the genesis of the book, Malamud in fact stressed that he had Brooklyn—and the Dodgers—in mind when conjuring up The Natural, rather than any one event or any team in Philadelphia or Chicago. In Conversations with Bernard Malamud, the author observed that the book “was the experience of being a kid in Brooklyn. I lived somewhere near Ebbets Field. The old Brooklyn Dodgers were our heroes, our stars, like out of myths. Since the stadium was that near, it had to concern you.” Malamud continued, “I didn’t play much baseball as a kid but I went to Ebbets Field and Yankee Stadium, I saw Babe Ruth, Dazzy Vance, and enjoyed the Brooklyn Dodgers in action.” He added that ballplayers “were the ‘heroes’ of my American childhood. I wrote The Natural as a tale of a mythological hero… [I] tried to use [mythology] to symbolize and explicate an ethical dilemma of American life.”

On another occasion, Malamud told Paris Review interviewer Daniel Stern, “As a kid, for entertainment I turned to the movies and dime novels. Maybe The Natural derives from Frank Merriwell as well as the adventures of the Brooklyn Dodgers in Ebbets Field.” (In this interview, he also declared, without citing Waitkus or any other baseball figure, “Events from life may creep into the narrative…” and “When I start I have a pretty well-developed idea what the book is about and how it ought to go, because generally I’ve been thinking about it and making notes for months, if not years.”) In a talk given at Bennington College in 1984, two years before his death, Malamud noted, “Baseball had interested me… but I wasn’t able to write about the game until I transformed game into myth, via Jesse Weston’s Percival legend with an assist from T. S. Eliot’s ‘The Wasteland’ plus the lives of several ballplayers I had read, in particular Babe Ruth’s and Bobby Feller’s. The myth enriched the baseball lore as feats of magic transformed the game.” In all these discussions, Malamud clearly does not cite Eddie Waitkus.

During the summer of 1949, the writer and his family moved from New York City to Corvallis, Oregon, where he began teaching at Oregon State University. It was here where the bulk of The Natural was written. In a detailed, superbly researched article, “‘Them Dodgers is My Gallant Knights’: Fiction as History in The Natural,” Harley Henry offers what is perhaps the definitive connection between Waitkus and Hobbs: “We can assume that before leaving New York he had a baseball story in mind, though perhaps only a short story inspired by the shooting of the player Eddie Waitkus in June 1949, an event around which the first short section of The Natural is composed.”

In shaping The Natural, Malamud admittedly incorporated the public personas of Feller and Ruth and his youthful remembrances of the Brooklyn Dodgers. But Henry reported that he also “began to shape an ‘exile and return’ plot imitating current events, for which he fleshed out his conception of Roy—based on Feller and Ruth—with allusions to three other players, two of them active at the time: Joe Jackson, Ted Williams, and Sal Maglie.” He added that “Roy Hobbs is an amalgam of Feller’s youthful innocence, Ruth’s hungry prowess, Williams’s hostility and pride, and Jackson’s natural but corruptible talent.”

Roy Hobbs starts out as a teen pitching phenom who travels by train for a tryout. His experiences on board mirror that of the young Bob Feller as he journeyed to join Cleveland in 1936. They are described in Strikeout Story, Feller’s 1947 autobiography, a copy of which, according to Henry, Malamud brought with him to Corvallis. Additionally, another episode in the book—Hobbs’s strikeout of Walter “The Whammer” Wambold, clearly a Babe Ruth clone—mirrors the untested Feller’s whiffing of eight St. Louis Cardinals in an exhibition game. And Hobbs’s transition from potentially great pitcher to fence-busting slugger reflects the career of the Bambino. “Ruth’s legend, and its retellings after his death in 1948,” noted Henry, “were matters Malamud could not possibly ignore when he began conceiving a baseball hero that very same year.”

Hobbs’s desire to be acclaimed the best damned ballplayer ever is pure Ted Williams—and, like Teddy Ballgame, he wears number 9 in the movie. The inspiration for “Wonderboy,” Hobbs’s hand-carved bat, could be Shoeless Joe Jackson’s lumber, which he called “Black Betsy.” (In his review of The Natural, Harry Sylvester described “Wonderboy” as a “trick bat—not unlike that used by Heinie Groh of the Cincinnati Reds back in the Twenties…”) Hobbs’s coming to the majors and his heroics for the New York Knights parallel the plight of Sal Maglie, who debuted with the New York Giants in 1945 and summarily was banned from professional baseball by Commissioner Happy Chandler after joining the Mexican League. Maglie, like Hobbs, was in his thirties when he resurrected his career, returning to the Giants in 1950 and sparking the team with an 18–4 won-lost record. At the novel’s finale, a newsboy’s query of “Say it ain’t true, Roy?” (in response to allegations that Hobbs threw a ballgame) echoes the legendary “Say it ain’t so, Joe?” question put to Shoeless Joe Jackson regarding his participation in the 1919 Black Sox scandal. And Hobbs’s banishment from the game mirrors the expulsion of Jackson and his White Sox cohorts.

Hobbs’s smashing a homer that breaks the face of a clock, resulting in a shower of broken glass, may embody the flight of a ball hit by the Boston Braves’ Bama Rowell in the second inning of the second game of a doubleheader at Ebbets Field on May 30, 1946. The ball smashed into the face of the Bulova clock that adorned the top of the scoreboard, spraying Dodgers right fielder Dixie Walker with falling glass. Furthermore, it may be said that the pre-Hobbs New York Knights are a version of the inept Brooklyn Dodgers of the 1930s. The Knights’ owner, Judge Goodwill Banner, shares similar characteristics with Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey, starting with a propensity for cheapness.

Clearly, as he shaped The Natural, Bernard Malamud had in mind a range of baseball facts and folklore. The near-murder of Eddie Waitkus, the Fightin’ Phillie and Whiz Kid, was just one of them.

The Phillies and The Natural: A Cameo Appearance

If Rocky Balboa slugged home runs in Connie Mack Stadium instead of opponents in a boxing ring, one might boast of Philadelphia being the locale of at least one beloved baseball film. But such is not the case. Regrettably, the Phillies and A’s—unlike the teams in New York, Chicago, or Brooklyn—rarely have been represented in any baseball film, good or bad. However, the Phillies do make a cameo appearance in the screen version of The Natural, as well as the novel upon which it is based.

The New York Knights may be a fictional team, but their opponents are real-life National League nines. The Knights’ ineptitude is summarized in a pair of onscreen newspaper headlines: “Phils Blank Knights” and “Knights Lose—Philly Wins Four to Three.” The Knights and Phillies also match up in Roy Hobbs’s big league debut. It’s the bottom of the seventh inning, and the Philadelphia nine lead the New Yorkers by a 4–3 score. The Knights are at bat, a runner leads off first, and Hobbs is called on to pinch hit. Pop Fisher, the Knights manager, cheers him on by yelling, “Alright Hobbs, knock the cover off the ball.” But no one expects that this literally is what the rookie will do once he swings and bat meets horsehide. (In the novel, Fisher’s line is, “Knock the cover off of it.” After Hobbs does just that, Bernard Malamud writes, “Attempting to retrieve and throw, the Philly fielder got tangled in thread.”)

ROB EDELMAN is the author of “Great Baseball Films” and a frequent contributor to “Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game.” He is a Contributing Editor of “Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide” and is co-author of “Matthau: A Life” and “Meet the Mertzes,” a double biography of “I Love Lucy’s” Vivian Vance and celebrated baseball fan William Frawley. He teaches film history at the University at Albany–SUNY and is an interviewee on extras on the DVD of “The Natural.”

SOURCES

Books

Alan Cheuse and Nicholas Delbanco, editors, Talking Horse: Bernard Malamud on Life and Work (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996).

Philip Davis, Bernard Malamud: A Writer’s Life (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Charles DeMotte, “Baseball Heroes and Femme Fatales,” The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture: 2002 (Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland & Company, 2002).

Rob Edelman, Great Baseball Films (New York: Citadel Press, 1994).

Kenneth T. Jackson, editor, Dictionary of American Biography, Supplement 9: 1971–1975 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1994).

Steve Johnson, Chicago Cubs Yesterday & Today (Minneapolis: Voyageur Press, 2008).

Marcus Klein, After Alienation: American Novels in Mid-Century (Cleveland: World Publishing Company, 1964).

Bruce Kuklick, To Every Thing a Season: Shibe Park and Urban Philadelphia 1909–1976 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991).

Lawrence M. Lasher, editor, Conversations with Bernard Malamud (Jackson and London: University Press of Mississippi, 1991).

Wil A. Linkugel and Edward J. Pappas, They Tasted Glory: Among the Missing at the Baseball Hall of Fame (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1998).

Bernard Malamud, The Natural (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2003).

G. Richard McKelvey, Lost in the Sun: The Comebacks and Comedowns of Major League Ballplayers (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2008).

Alyssa Milano, Safe at Home: Confessions of a Baseball Fanatic (New York: William Morrow, 2009).

Joshua Prager, The Echoing Green: The Untold Story of Bobby Thomson, Ralph Branca and the Shot Heard Round the World (New York: Pantheon Books, 2006).

Richard Scheinin, Field of Screams: The Dark Underside of America’s National Pastime (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1994).

John Theodore, Baseball’s Natural: The Story of Eddie Waitkus (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2002).

John Thorn, Pete Palmer, Michael Gershman, and David Pietrusza, Total Baseball, Fifth Edition (New York: Viking, 1997).

Newspaper and Magazine Articles/Papers

Ira Berkow, “Sports of the Times: The Shooting of a Baseball Idol,” The New York Times, August 12, 1988.

Peter Carino, “History as Myth in Bernard Malamud’s The Natural,” NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture, Fall 2005.

Gordon Edes, “Ballplayers Are at the Mercy Of Twisted Fans,” South Florida Sun Sentinel, July 9, 1995.

Ron Fimrite, “A Star With Real Clout,” Sports Illustrated, May 7, 1984.

Jim Harper, “Daley’s Diamond: The Baseball Writing of Arthur J. Daley,” American Society for Sport History, 1989.

Harley Henry, “‘Them Dodgers is My Gallant Knights’: Fiction as History in The Natural,” Journal of Sport History, Summer 1992.

Louther S. Horne, “Baseball Star Shot By Girl Fan Rallies,” The New York Times, June 16, 1949.

——. “Gain by Waitkus ‘Near Miraculous’; Operation on Ball Player Succeeds,” The New York Times, June 81, 1949.

Carolyn Kellogg, “Batter up! 9 baseball books to kick off the season,” Los Angeles Times, March 31, 2011.

Bob Minzesheimer, “John Grisham tosses out a baseball morality tale,” USA Today, April 9, 2012.

Mervyn Rothstein, “Bernard Malamud Dies at 71,” The New York Times, March 19, 1986.

Daniel Stern, “Interviews: Bernard Malamud, The Art of Fiction No. 52,” The Paris Review, Spring 1975.

Harry Sylvester, “With Greatest of Ease,” The New York Times, August 24, 1952.

“A Talk With B. Malamud,” The New York Times, October 8, 1961.

“Arraigned, Indicted, Held Insane in 3 Hours, Girl Who Shot Waitkus Is Sent to Asylum,” The New York Times, July 1, 1949.

“Girl Who Shot Waitkus Gains,” The New York Times, September 14, 1950.

“Waitkus Assailant May Go Free,” The New York Times, August 8, 1950.

DVD

“A Natural Gunned Down: The Stalking of Eddie Waitkus,” documentary extra on the Director’s Cut DVD release of The Natural.

Websites

(The Glory of Baseball) http://thegloryofbaseball.blogspot.com/2005/06/real-life-roy-hobbs.html.