Ford Frick and Jackie Robinson: The Enabler

This article was written by David Bohmer

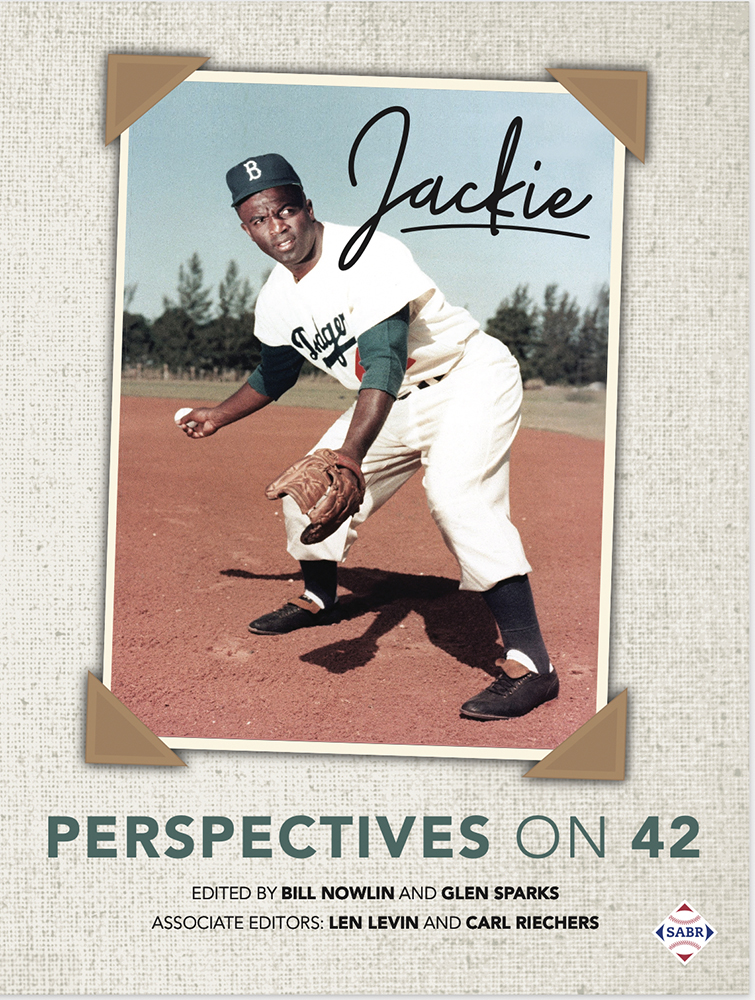

This article was published in Jackie Robinson: Perspectives on 42 (2021)

Ford Frick, president of the National League in 1947, is not the first person who comes to mind concerning Jackie Robinson and the integration of baseball, though he deserves more consideration than he has been given. While no other individual rivals the role played by Branch Rickey in breaking the game’s color barrier, other than Robinson himself, many others were certainly important.

Ford Frick, president of the National League in 1947, is not the first person who comes to mind concerning Jackie Robinson and the integration of baseball, though he deserves more consideration than he has been given. While no other individual rivals the role played by Branch Rickey in breaking the game’s color barrier, other than Robinson himself, many others were certainly important.

Some of Robinson’s teammates stand out, particularly Pee Wee Reese, who was from a Southern state and yet demonstrated early support for Jackie. Manager Leo Durocher played a major role until he was banned from the game for a year, just before the start of the 1947 season. His strong backing helped overcome resistance on the part of some of the Dodgers’ Southern players during spring training in 1947. The relatively new commissioner, Happy Chandler, also has received recognition, though his role may have been far less important than once thought.1

In actuality, Frick was the only individual who had a formal role to play other than Rickey in integrating baseball. All major-league players had to be approved by the respective league president before they were allowed on the club roster. The only person other than the Dodgers who could formally block Robinson, except, perhaps, under the “best interests of baseball” clause, was the National League president – Frick.

The personal history of Ford Frick does not appear to have been one that would shape a progressive mindset on the issue of baseball integration. He was born in 1894 in Wawaka, Indiana, a small railroad town in the northeastern part of the state, and grew up in a similar community, Brimfield, five miles to the east. There were no Blacks in either town or any in his public schools. At 15, he spent a year in Fort Wayne, Indiana, where he briefly attended a business school and worked as a copyboy for a local newspaper. Again, any contact in the city with African Americans would have been very limited at best. His four years as a student at DePauw University would not have broadened his horizons either. The only African-American student in attendance was there part-time in the School of Music, a distinct entity separate from the College of Liberal Arts, where most students like Frick studied.2

After graduation from DePauw in 1915, Frick moved to Colorado, where he spent most of his seven years in the state working for a newspaper in Colorado Springs. Again, his interaction with Blacks would have been limited, at best. Even his move to the far more cosmopolitan New York City to work as a sportswriter for the Hearst papers would not have expanded his horizons. His coverage focused on baseball, which was, of course, fully segregated at the time, and he lived in Bronxville, New York, an almost exclusively hite suburb of the city. His fellow sportswriters were all Caucasian. None of these experiences or exWposures would have broadened his horizons on race.

In fact, one experience would have seemed to foster the opposite perspective. During his time as a sportswriter from 1922 to 1933, Frick became one of the founders of the New York Base Ball Writers Association of America, an organization of men in the city who covered the sport. It was, reflecting the era, an all-White organization. The association quickly expanded to other cities, but the New York group became notorious for putting on the major baseball social event of the year, held in early February in conjunction with the annual scheduling meetings for the two major leagues.

Consequently, the event drew all the top brass of the sport and quickly evolved into a roast of the game’s elite, performed by some of the writers. During the first decades, that roast was always done in the form of a minstrel show.3 The writers would dress up in blackface to look the stereotypical part of minstrel singers. For as long as he was a sportswriter in New York, Frick was one of the key participants in the show. In essence, like many Americans during this period, Frick unquestionably participated in helping to perpetuate racial stereotypes.

Frick’s performances in the Association’s annual event ended in March 1934 when he was hired as head of the National League Service Bureau, the promotional arm of the league offices. He would remain a regular attendee during his long baseball career. At year’s end, when John Heydler retired as National League president, Frick was named to replace him, beginning what would become a 17-year tenure in that capacity, ending only when he was elected commissioner in 1951.

The new position still would not have had any meaningful impact on Frick’s interaction with or perception of minorities. While he no longer dressed in blackface, his daily interactions saw little change, as the game he presided over remained a White man’s game. The only on-field interaction between Black and White players occurred in offseason barnstorming and exhibition games. There is no evidence that Frick attended such games, which might have broadened his horizons had he done so.

During this period, in the thick of the Great Depression, interest in integrating the game began to grow, though much of the advocacy came from African-American or Communist newspapers. Reflecting that interest, Wendell Smith, assistant sports editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, a Black newspaper, was able to arrange an interview with Frick in February of 1939, in the lobby of a Pittsburgh hotel, to ascertain his thoughts on the possibility of integration. Why Frick was chosen is unclear, although his being a relative newcomer to the front office compared with AL President William Harridge and Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, combined with the fact that Pittsburgh was a National League city, may have made him seem more accessible. Frick’s comments, however, certainly did not give Smith any hope that the NL president would have any inclination to be a crusader for change.

In answering Smith’s questions, Frick contended that the largest obstacles to bringing a Black man into baseball were the players and the fans. Frick said many in both groups were not ready to accept integration and would create problems both on the field and in the stands. He also pointed out that spring training in the South would present major difficulties due to Jim Crow and that travel to many major-league cities would also offer challenges since many hotels and restaurants did not accept Black guests. Frick further stressed that such separation of players could impact a team’s cohesiveness. In addition, he emphasized that the owners and executives of baseball were not the barriers to ending segregation and even pointed out that the sport had no formal policy barring Blacks.4

Smith published the interview and then followed it up with numerous additional sessions during the season with National League players and managers. His articles on those interviews revealed that there was less opposition to integration, at least on the part of those whom Smith questioned, than what Frick had suggested.5 The clear implication of the interviews, when Smith presented them in his articles, was that the barrier was exactly where Frick said it wasn’t – with the owners and other executives. While the various articles by Smith never appeared in the White press, taken in context with the comments of the players and managers questioned, Frick’s assertions implied, at least to later historians of the game, that the NL president may himself have been one of the major barriers to integration.

Interestingly, Smith’s interview with Frick was not the first time the league president had been quoted in the African-American press. In August of 1936, the Chicago Defender ran a story, originally printed in the Communist Daily Worker, that quoted Frick on the status of Blacks playing in the major leagues. Less than two years into his job as NL president, Frick claimed he did “not recall one instance where baseball had allowed either race, creed or color to enter into the question of the selection of its players.” He quickly added that the issue involved all clubs in the league and was … “not within the province or the authority of the league president to express an official opinion in the matter.” As he did later in the Smith interview, he mentioned the problem in Southern states with spring training, and then stated what would be a position he held throughout his baseball career, that “(t)he whole subject is a ‘sociological problem,’ something society, not the big leagues, must solve.”6 Consistent with the Smith story, Frick would deny any formal barrier and then offer other reasons as to why there were no Blacks playing in the majors or minors.

In fairness, the perception of Frick being a major barrier may not be totally appropriate. Given his regular interaction with NL owners, he clearly understood in 1939, after almost five years in the job, and even as far back as 1936, that none of the magnates had expressed any interest in signing Black players. He also was well aware that it was those same owners who had hired him, would renew his contract and, in between, pay his salary.

Even if the likelihood was limited that his comments to a Black or communist newspaper journalist would ever be known by any of his club owners, he wasn’t inclined to take that risk. Further, not all of his comments were off the mark. Robinson in 1947 did have problems with players, managers, and fans. There were also difficulties during spring training in Florida and on being allowed in hotels and restaurants on Dodgers road trips during the season. His perception that a Black player would have difficulties was certainly proved accurate during Robinson’s rookie season. Nonetheless, Frick’s comments left the impression in later years, thanks in large part to Chris Lamb’s article about the Smith interview, that the National League president was one of the barriers to baseball integration.

That perception had actually been created well before Lamb’s article, thanks to allegations made by Bill Veeck in his classic 1962 book Veeck as in Wreck. Veeck claimed that Frick had blocked him from acquiring the Philadelphia Phillies in 1942-43 because he had planned to field a team of Black players. The maverick former owner also claimed in the book that the NL president subsequently bragged to others that he had stopped Veeck from buying the team and thus “contaminating the league.”7

Frick, still commissioner at the time, never denied the claims, but he also never commented on numerous other criticisms of him that Veeck leveled in the book. Interestingly, the topic of the Phillies story has in recent years become an ongoing debate among baseball scholars as to the extent of veracity of Veeck’s allegations. Jules Tygiel, in his classic study of Robinson and integration, reaffirmed Veeck’s story, including the claim about Frick. Other than citing Veeck’s book, however, his only further evidence was an interview he did with the maverick executive in 1980, when he still owned the White Sox for a second time. As the definitive study of the Robinson story, Tygiel’s book furthered the perception of Frick as an ardent opponent of integrating the game before 1947.8 In essence, his study strengthened Veeck’s earlier claims.

In spite of all the research that’s been done since, with some authors questioning and others supporting Veeck’s claim, the actual facts in the attempt to purchase the Phillies are quite limited and rather elusive.9 The most salient details come from a special meeting of the National League’s board of directors held at Frick’s offices on November 4, 1942. The meeting was called by the NL president due to the extremely precarious financial situation of the Phillies as well as the extent to which the league was involved financially because of its extensive loans to the club.

Phillies owner Gerald Nugent claimed during the meeting that Veeck had approached him about buying the club, indicating that the owner of the minor-league Milwaukee Brewers had some local money behind him. However, Nugent added that he hadn’t “heard back from him and that was three weeks ago.”10 Later in the meeting, Frick indicated that he, too, had been approached by Veeck, even before the prospective buyer had met with Nugent. Frick claimed Veeck had indicated being able to meet the minimum amount expected by the shareholders, estimated at $154,000, but added that it was unclear if the total figure the prospective buyer had in mind was $200,000 or $400,000, further acknowledging that either number was unacceptable to Nugent. He too had heard nothing further from Veeck since. No mention was made of any plans he might have had for the club.11

In subsequent meetings of the board, on November 30 and at the annual meeting of the owners over the next two days, a potential buyer was mentioned, but no name was offered in the minutes. The tenor of the discussion suggested it wasn’t Veeck, because he had specifically been discussed at the earlier meeting. By the next meeting of the National League, on February 9 in New York, a deal had been reached to sell the club to a partnership headed by William Cox. After the November 4 meeting, Veeck was never mentioned again as a potential buyer in any league records.

Other than the acknowledgement of Veeck’s interest by Frick and Nugent in early November and also a small piece in The Sporting News in October of 1942, there is no evidence that a formal offer was ever made. None of the primary sources suggest that a Veeck offer was rejected either directly or behind the scenes. There is also no evidence that Veeck ever had a formal meeting with Landis. There is also no historical record that Frick ever bragged to others that he had blocked Veeck from buying the team, or any indication of how Veeck would have heard that the league president had done so.

All assertions that this happened are based upon interviews with various parties that took place well after the Phillies were sold, in some cases many years later. Beyond the fact that Veeck had expressed interest and then did not appear to follow through on it, there is nothing in any primary sources to verify the rest of his allegations. Whatever Frick’s views and regardless of what he knew of Veeck’s intent, he did not appear from the sources to have blocked any effort to purchase the woebegone Phillies, a club both Frick and the NL owners were desperate to see someone buy to get the financial burden off their backs.

While Frick may not have had much of a relationship with Veeck in 1943, he did have a friendship with Branch Rickey, the man who would ultimately integrate the game. It became even closer around the time the Phillies were sold, when Rickey left the Cardinals to replace Larry MacPhail as president of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Both men now resided in the New York area.

Frick and Rickey also shared many commonalities in their backgrounds. They both grew up in small Midwestern communities. Both were products of deeply religious families. Both went to small Methodist liberal-arts colleges in the Midwest. Before moving to Brooklyn, the two had also interacted on many matters after Frick became NL president, including the suspension of Dizzy Dean and the threats Commissioner Landis presented to the Cardinals farm system that Rickey had so carefully developed. The two had also interacted regularly for almost a decade at the various league meetings and obviously had even more opportunities to cross paths when Rickey moved to Brooklyn.

There is no formal record of when and how often the two might have discussed the issue of integration before or after Rickey signed Robinson to a minor-league contract in late 1945, but it is difficult to imagine there weren’t conversations between them, especially given Frick’s role in approving all players in the National League.

That relationship may have been of considerable importance in August of 1946 when the MacPhail Commission report was presented to a joint meeting of the two leagues. The report, so named because Larry MacPhail, part-owner of the Yankees, chaired the committee that drafted it, was largely meant to address problems of labor unrest in the majors and well as players jumping to the Mexican League.

During its numerous meetings in the summer of 1946, the committee, which included the two league presidents, Tom Yawkey of the Red Sox, Sam Breadon of the Cardinals, and Phil Wrigley of the Cubs, was well aware that Jackie Robinson was playing for the Montreal Royals, the Dodgers’ Triple-A club. In fact, it spent close to three pages of its 25-page report addressing the “Race Question.”

In the end, the report made no formal recommendations as it had on numerous other issues, though it did suggest that “(t)he individual action of any one Club may exert tremendous pressures upon the whole structure of Professional Baseball, and could conceivably result in lessening the value of several Major League franchises.” It added: “Your Committee does not desire to question the motives of any organization or individual who is sincerely opposed to segregation or who believes that such a policy is detrimental in the best interests of Professional Baseball.”12

All six committee participants, including Frick and William Harridge, the American League president, signed off on the report. At the joint meeting of the two leagues, the report’s recommendations were adopted unanimously by both leagues, at which the Dodgers were represented by Branch Rickey.13

However, the segment of the report concerning integration was never formally brought up at the meeting in any fashion, even though Rickey claimed a year and a half later, in a speech at Wilberforce College in Ohio, that owners had voted 15 to 0 against integration, with Rickey abstaining.14 There was no such vote in the recorded meeting. Only issues like the creation of an executive committee with player representation, a minimum wage, spring-training money, and research to start a pension plan were actually enacted.

Since there was no segment of the meeting that was off the record, it is fair to conclude that the discussion and vote may never have taken place that day.15 Knowing the potential controversy it would generate, and likely aware of Rickey’s plans with Robinson, it is possible that Frick, the committee member most inclined to have been supportive of Robinson, helped to persuade the other committee members and owners to exclude that segment of the report from any action. If so, Frick helped to avoid a potential controversy from coming to a head.16

What did remain clear was that Frick was the only person, other than the Dodgers ownership, who could have blocked Jackie Robinson from joining the club’s roster. Any major-league ballplayer in each league could not be added to the roster of their club until he was approved by the president of the respective league. In essence, Frick had to sign off on Robinson’s contract before he could become a Dodger.

In theory, the commissioner, Happy Chandler, could have weighed in on the matter, but only by blocking Robinson under the “best interests of baseball” clause. That wasn’t likely, given the aftermath of World War II, even though most owners still appeared to oppose integration. Rickey himself declared the issue of Robinson to be solely “a league matter,”17 thus not involving Chandler. The general manager’s decision to bring Robinson up from Montreal to the Dodgers and Frick’s signature on the contract were all that were necessary to make baseball and national history.

It would not be the last time, though, that Frick would play an important role in the Robinson saga. From the time Robinson was brought into what had been “White” baseball, there were suggestions that some ballplayers would refuse to play on the same team. When Robinson was placed on the Triple-A Montreal Royals, their manager, Clay Hopper, who was from Mississippi, questioned having a Black man on his club.18

There was major opposition from Southern ballplayers in the 1947 Dodger spring-training camp, precipitating concern that there would be a player rebellion. Leo Durocher’s efforts helped to stop that threat.19 By the time the season started, the Dodgers players seemed ready to accept Robinson as a teammate. It was less clear, however, whether players on other teams would be willing to play against him.

That issue came to a head in early May when the St. Louis Cardinals came to Brooklyn for their first series of the season against the Dodgers. Sam Breadon, owner of the Cardinals, was deeply concerned that some of his players would refuse to take the field against Robinson, enough so that he made a special trip to New York to discuss the matter with Frick. The understanding of what happened next has varied somewhat, depending upon the source.

At one level, there supposedly was no real threat of a strike. It was merely a lot of talk on the part of some players, but nothing beyond that. According to other accounts, Frick met with Breadon and gave the Cardinals owner the message to convey to the strike-threatening players, convincing them there would be severe repercussions for anyone who refused to play. Other versions suggested that Frick himself talked with the players who intended to strike and threatened them that they would be putting their baseball futures in jeopardy. A recent article even asserts that nothing may have happened because there had never been any real threat of a strike in the first place.20

In many ways the actual story is as elusive as was Bill Veeck’s attempt to buy the Phillies. Other than the accounts written directly after the series in the New York press, especially the original story by Stanley Woodward in the New York Herald Tribune on May 9, along with stories in the New York Times on both May 9 and 10, there is no primary evidence other than the later recollections of Frick, Breadon, Cardinals manager Eddie Dyer, and the players.

The Herald Tribune quoted Frick as having given a powerful speech but the NL president later claimed the story was overblown. The Times on May 10 quoted Frick as saying it was a dead issue, that “a mountain had been made out of a molehill, anyway.”21 The article went on to say that Breadon denied the story, that he had only come to town to help his slumping Cardinals. Dyer echoed Breadon’s version.22 Whatever occurred, it was clear that all parties involved didn’t want the publicity it was receiving in the press and thus shared an interest in downplaying the story.

Those desires from the parties directly involved did not stop Arthur Daley of the Times from praising Frick for his actions the following Tuesday in his “Sports of the Times” column. Daley concluded, based in part on the original Woodward article, that Frick had dealt the anti-Robinson movement “a sledgehammer blow from which it will never recover.”23 Essentially, in assessing the various accounts, something had unquestionably transpired when the Cardinals came to Brooklyn that caught the attention of local sportswriters and, whatever occurred, its outcome ended any threat of a strike. Further, Frick had played a role in that event, to which he would often proudly refer in later years.24

That role, whatever it may have been, and his approval to add Robinson to the Dodgers roster were likely instrumental in Frick joining Robinson and Rickey as the recipients of two Thomas Jefferson prizes in 1948. The awards were presented by the Council Against Intolerance in America. Robinson, for his efforts on the diamond, received an award for “the advancement of democracy during 1947.” Rickey and Frick were recipients for having broken “the color barrier in American baseball.” Both awards were decided by a nationwide poll of officials of 1,000 civic organizations along with editors of 500 newspapers. Rickey and Frick were ranked first in the public-service classification of the awards.25

The honors were presented at the annual banquet in New York on April 11, where 250 witnessed Frick accepting the award.26 Neither Rickey nor Robinson attended the event, perhaps because the baseball season had not started yet and both were still engaged in spring training in Florida. In any case, all three had received recognition for what had unquestionably been one of the most im-pactful events in the country in 1947. It was Frick, not Chandler, who was seen as the facilitator of Robinson integrating baseball.

As other clubs integrated, especially the Indians and Giants, and the Dodgers added other Black players, Robinson became a more accepted part of baseball. It was also inevitable that he would be treated like other players, neither singled out favorably or unfavorably due to his race. After the 1948 season, Robinson was released from his promise to Rickey to keep his emotions under control while playing. Once freed of that pledge, Robinson, known for his temper, was likely to come under the perusal of the league office, still presided over by Frick.

There is no account of Robinson actually being fined for misbehavior while Frick remained NL president, with nothing at all reported in 1949 and 1950, but there was a major incident reported early in the 1951 season. Robinson claimed that some of the NL umpires were “on him” and he expected to hear from Frick about an incident with Babe Pinelli.27 The specifics of the Pinelli incident were never explained, but two weeks later Frick weighed in on Robinson’s behavior, saying that he “was tired” of his “popping off, and all that business” and that he would control the player if Brooklyn couldn’t. Walter O’Malley, now majority owner of the club, said Robinson “has the full support of the Dodger organization.”28 Nothing more was published about Robinson’s conflicts with umpires, suggesting that after the early-season publicity, the issue had cooled off and was resolved quietly.

Once Frick became commissioner later in 1951, the oversight of Robinson’s on-field behavior came under the jurisdiction of the new NL president, Warren Giles. There was one matter, however, that the commissioner, overseeing the best interests of the game, couldn’t avoid. On November 30, 1952, Robinson appeared on a New York television show called Youth Wants to Know and near the end of the program one teenager asked him if he thought the Yankees were “prejudiced against Negro players”? After a pause, the Dodger responded candidly: “I think the Yankee management is prejudiced. There isn’t a single Negro on the team and very few in the entire Yankee farm system.”29

Unsurprisingly, the Yankees front office countered his claims and filed a complaint with Frick. The issue hit the city newspapers as the Yankees applied pressure on the commissioner to censure Robinson. Frick did speak with Robinson, asking him to “soft-pedal” such comments going forward. At the same time, he added and stressed publicly that a ballplayer “still has the right of free speech.”30 The issue passed from coverage, but it appeared that Robinson toned down his comments without tempering his views on numerous matters. Years later, Robinson claimed that Frick’s support of his right of free speech was an important part of ensuring his success in integrating the game.31

Many years after Robinson retired from baseball, but while Frick was still commissioner, the man who had integrated the majors did offer a criticism of Frick’s leadership. Robinson had published a book in 1964 titled Baseball Has Done It, a series of stories mostly by Black players about their experiences in baseball as minorities, in some cases having broken the color barrier on their club. Much of the theme centered on the growing civil-rights movement in the South in the early 1960s and the effort by Blacks to gain rights that were still denied them in the formerly Confederate states. The stories contained many encounters with discrimination in the South against African-American players during spring training as well as while they played for minor-league clubs in many of the cities.

Near the end of the book, Robinson asserted: “Baseball, which has profited greatly both at the box office and in the quality of play from Negro participation, should stop ducking the broader issue of civil rights. … You, Mr. Commissioner, are a general who doesn’t know he has an army or is in a war.”32 In essence, baseball should have put more pressure on the South to force an end to discrimination as well as to protect its Black players.

Ironically, earlier in the book, Frick had actually provided an explanation for his lack of having done so: “Baseball’s function is not to lead crusades, not to settle sociological problems, not to become involved in any sort of controversial racial or religious question.”33 Their independent comments in the same book demonstrated how far apart their views were as the civil-rights movement in the South came to a head at the end of Frick’s tenure.

Frick’s comments in Robinson’s book are in actuality a fair summary of his views and, given his comments printed in the Defender in 1936, seem to have been consistent throughout his baseball career. Ford Frick was never a crusader. It was not in his nature to get out in front of an issue, especially not to push his collection of magnates too far in directions they didn’t want to go. At the same time, his inclination and personal beliefs tended heavily toward fairness. While his life experience never produced many interactions with African-Americans, he was not hesitant to step into a situation if he felt it fair and proper to do so. Hence, if Rickey wanted to integrate the Dodgers by adding Robinson to the 25-man roster, Frick would support it.

Further, if others attempted to bring obstacles to prevent Robinson from playing, Frick would not hesitate to intervene. While he was never proactive in the integration of baseball, he played an important role in ensuring that it came about and would be maintained as Robinson’s and other Black players careers continued. Thus, it is not surprising, as shown earlier in this essay, to see Robinson both praise Frick for his personal support and criticize him for not being more proactive on African-American matters in later years. While not a crusader, Frick was consistent in the way he treated Robinson and other ballplayers, with no favoritism or discrimination, but rather with equal support for their careers in baseball. In that way, Frick was an important component of Jackie’s story, as Robinson himself would later recognize.

DAVE BOHMER, a Cleveland native, remains an avid fan of his hometown team. He taught baseball history for over a decade at DePauw University, his alma mater, where he became interested in Ford Frick after learning he was also an alum. He has been a SABR member since 2007.

Notes

1 John Paul Hill, “Commissioner A.B. ‘Happy’ Chandler and the Integration of Major League Baseball: A Reassessment,” Nine: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture, 19, no. 1 (2000): 28-51. Hill points out that Chandler’s role was not a formal one in activating Robinson.

2 Wes Wilson, email message to author, February 18, 2020. Wilson is a former archivist at DePauw University.

3 “Baseball Diners Cheer for Walker,” New York Times, March 22, 1926: 21, references Frick and the minstrel show during the annual gathering.

4 Chris Lamb, “Baseball’s Whitewash: Sportswriter Wendell Smith Exposes Major League Baseball’s Big Lie,” Nine: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture, 18, no. 1 (2009): 1-2. Lamb expands on the topic in his book Conspiracy of Silence: Sportswriters and the Long Campaign to Desegregate Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 133-35.

5 Lamb, “Baseball’s Whitewash”: 7-16.

6 Ted Benson (from the Sunday Worker). “‘League Open to Negroes’ Says Frick, League Prexy,” Chicago Defender (National edition), August 29, 1936: 13.

7 Bill Veeck with Ed Linn, Veeck as in Wreck (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), 171-72.

8 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 40-41.

9 The Phillies story has certainly been the subject of considerable debate over the last two decades plus. It was started by David Jordan, Larry Gerlach, and John Rossi in “A Baseball Myth Exploded: Bill Veeck and the 1943 Sale of the Phillies,” National Pastime (SABR: 1998): 18. Their article basically attempted to debunk the entire story. Their conclusion was partially questioned in 2006 in Jules Tygiel, “Revisiting Bill Veeck and the 1943 Phillies.” Baseball Research Journal, (2006): 109-114. Tygiel essentially drew the same conclusion as does this paper, that there are very limited records to verify the claim. He did note that evidence showed there were indications of Veeck’s idea of an integrated club during the war much earlier than his 1962 book made it public, although nothing that dated back to 1942 or 1943. In his well-researched biography of Veeck, Paul Dickson, Bill Veeck: Baseball’s Greatest Maverick (New York: Walker & Company, 2012), argues that the Phillies story was true, devoting part of a chapter and a 10-page appendix to the issue. See pages 79-80 and 357-66. However, an article a year later again pointed out what Tygiel had claimed earlier, that no new primary evidence was presented. See Norman L. Macht and Robert D. Warrington, “The Veracity of Veeck,” Baseball Research Journal, 42, no.2 (2013). In particular, they had a strong response to Dickson’s claim that Frick never denied Veeck’s allegations against him. “Frick adopted the diplomatic stance of silence, as people often do in refusing to dignify an unfounded accusation with a response.” There are numerous cases during his career in baseball where Frick indeed behaved in such a fashion, choosing not to respond publicly to negative comments and thus dignify them, as I have found in my research on him.

10 National League Board of Directors Meeting Minutes, November 4, 1942, 90-91.

11 National League Board of Directors Meeting Minutes, 137.

12 Report of Major League Steering Committee for Submission to the National and American Leagues at their Meetings in Chicago, August 27, 1946.

13 Joint Meeting of Major League Baseball Clubs, Blackstone Hotel, Chicago, August 28, 1946, 13. Rickey was absent at the start, but present soon after for all the votes.

14 Roscoe McGowen, “Rickey Agrees That Club Owners Might Not Recall Anti-Negro Vote,” New York Times, February 19, 1948: 31. In the issue the day before, Rickey had claimed the vote took place at the same meeting in April of 1945 at which Chandler was voted in as commissioner, claiming it had happened before Robinson had even played a game. In fact, Rickey had not signed Robinson until October of that year. He downplayed his Wilberforce assertion to claim he was merely trying to show how far baseball owners had progressed. in less than two years.

15 Joint Meeting, August 28, 1946, 1-31.

16 It may have come to a head the day before and Rickey may have been correct about a controversy and even a secret vote. On August 27 there was an unrecorded joint meeting of the owners. The minutes of the August 28 meeting twice, on pages 6 and 25, make reference to a session the previous day, implying that those in attendance on the 28th were there the day before. Further, the actual report states on its title page “For submission to National and American Leagues on 27 August, 1946.” The comments refer to “meetings,” unclear whether that meant the leagues met separately or that there was more than one meeting during the day on the 27th. In any case, there are no minutes recording the session(s). One can only surmise what went took place the day before, but it’s clear what action items were carried over to the following day. The issue of integration, still in the original report, was definitely not brought forward. It was also suggested by Rickey that copies of the “MacPhail Report” were collected after the meetings, most likely due to the acknowledgment in the report that the reserve clause had no legal standing, not because of the comments on integration. Without minutes or surviving attendees, what took place in Chicago on August 27 will likely remain unknown.

17 Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 425.

18 Tygiel, Experiment, 103-04.

19 Tygiel, Experiment, 168-73.

20 See Warren Corbett, “The Strike Against Jackie Robinson: Truth or Myth?” Baseball Research Journal 46 (2017), no. 1. Corbett’s conclusion is that Breadon overreacted, there was never a real threat, and New York sportswriters wrote about the event out of all proportion to what actually happened. Wendell Smith, Robinson’s traveling partner for the 1947 season, said it “made a better newspaper story than anything else.” However, much of Corbett’s conclusion appears to be based on supposition and comments that came much later from some who were on the Cardinals, not actual data directly after the event. The newspaper coverage at the time still remains the best primary source as neither Frick nor Breadon kept any records of the meeting. It is clear there was some concern at the start of the series that Cardinal players would boycott the game and that Frick appeared to play a role in preventing them from doing so. It is not surprising that both Frick and Breadon downplayed the issue since it was in everyone’s interest for the story to go away.

21 “Robinson Reveals Written Threats,” New York Times, May 10, 1947: 16.

22 “Robinson Reveals Written Threats.”

23 Arthur Daley, “The Passing Baseball Scene,” New York Times, May 13, 1947: 32.

24 John P. Carvalho, Frick,*: Baseball’s Third Commissioner (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. 2016), 123-26; Ford C. Frick, Games, Asterisks, and People (New York: Crown Publishers, Inc.), 97-98; Jackie Robinson, Baseball Has Done It (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1964), 113-14; and Buzzie Bavasi, email message to author, January 22, 2008. Bavasi, in particular, was adamant that Frick met directly with the players and threatened to remove them from baseball and keep them out for as long as he remained NL president. I had sent Bavasi an article on Frick for him to review in 2008, stating in it that whether the meeting with the Cardinals players actually occurred and who conducted it was unclear. He stated unequivocally that the meeting with Frick took place and that he was there to help arrange it. Obviously, like other sources, his comments stem from memory many years later.

25 “Major Flashes Column,” The Sporting News, February 25, 1948: 23. “Honor Robinson, Rickey: Frick Also Cited for Breaking Color Barrier in Baseball,” New York Times, February 16, 1948: 27.

26 “Intolerance Group Presents Awards,” New York Times, April 12, 1948: 23.

27 “Umpires Irk Robinson,” New York Times, April 21, 1951: 12.

28 “Dodger Office Backs Jackie; Ford Frick Explains Blast,” The Sporting News, May 9, 1951: 2.

29 Tygiel, Experiment, 295.

30 “Bavasi Berates Bombers,” New York Times, December 3, 1952: 47.

31 Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made (New York: Putnam Publishing Co., 1972), 102. Robinson added “Without that kind of support from some of the people in baseball who had power, I could not have made it, no matter how well I performed, no matter how loyal black people were.”

32 Robinson, Baseball Has Done It, 212.

33 Baseball Has Done It, 109.