From a Researcher’s Notebook (1984)

This article was written by Al Kermisch

This article was published in 1984 Baseball Research Journal

ORIGINAL BULLPEN PLACE FOR FRUGAL FANS

THE TERM “BULLPEN” IS generally believed to have come into baseball with the advent of relief pitchers who usually warmed up in the area where Bull Durham signs were located. The term, however, goes all the way back to the beginning of major league baseball itself, and its original meaning referred to a section set aside in some distant part of the ballpark where customers were literally herded in for a reduced fee after the game had begun.

The following item from the Cincinnati Enquirer of May 8, 1877, gives some clue to the original meaning of the word bullpen:

“The bull-pen at the Cincinnati grounds with its `three for a quarter crowd’ has lost its usefulness. The bleacher boards just north of the old pavilion now holds the cheap crowd, which comes in at the end of the first inning on a discount.”

And the following article from the Providence Journal of May 1, 1880, provides a good insight as to why the bullpen for spectators fell into disfavor:

“Last season the management established what is termed a ‘bullpen’ at the lower extremity of the grounds at Messer Park and after the fourth inning of a championship game persons by the payment of twenty cents were entitled to a seat therein. The home team received the entire revenue from the ‘pen,’ and in the course of the season, it amounted to a comfortable sum. Similar instructions were established at Cincinnati and Boston, but as considerable dissatisfaction has been expressed by the other clubs in the league, the Providence management has decided to remove this ‘pen,’ consequently, no admission will be granted except by the turnstile and the payment of the prescribed fee.”

SIX UNASSISTED OUTFIELD DPs FOR SPEAKER

Baseball’s record books are at variance on the record for unassisted double plays by an outfielder. One credits Tris Speaker with four for his career and shows him as the American League record-holder and sharing the major league record with Elmer Smith, while another book lists Speaker with six. Tris did, in fact, turn six unassisted DPs as an outfielder and owns the distinction of making two in one season twice – and with different teams at that.

The two record books agree that Speaker had unassisted double plays for the Boston Red Sox in 1909 and 1914 and two for Cleveland (April 18 and 29, 1918). But he actually made four for the Red Sox one in 1909, another in 1910 which long was overlooked, and two in 1914, the second of which also went undetected for years.

Speaker performed his 1910 unassisted DP on April 23 in the second inning of a game at Boston against the Philadelphia Athletics. With one down Harry Davis was hit by a pitched ball and promptly stole second. Danny Murphy hit a low drive to center, and Speaker snared the ball and continued on to second for an easy double play as Davis had taken off with the crack of the bat. The A’s, however, went on to win the game, 5-3 in 11 innings, with Eddie Plank the winner over Eddie Cicotte, both hurlers going all the way.

In 1914 Speaker accomplished the first of his two unaided DPs against Philadelphia Athletics at Boston on April 21 and then turned the trick again at Detroit on August 8. On that day he made his unassisted double play in the fourth inning of a game won by Boston, 5-2. With Harry Heilmann on second base and George Burns on first, Tris took Oscar Stanage’s short fly and easily doubled up Heilmann at second because both runners had taken off on a hit-and-run play.

Editor’s Note: Another SABR member, Ray Gonzalez, discovered the two additional unassisted double plays by Tris Speaker several years ago. His findings were presented to the Official Baseball Records Committee in 1980. One record book made the appropriate corrections, but the other somehow neglected to do so.

Speaker had a fabulous major league career, batting .345 for 22 seasons. He played on three world championship clubs, the 1912 and 1915 Red Sox and the 1920 Indians, a club he also managed. But if Speaker, who was approaching his thirty-ninth birthday, hadn’t been so intent on playing regularly, he could have been part of the 1927 New York Yankees, considered one of the greatest teams of all time. When Tris retired as Cleveland manager after the 1926 season, he received a flattering offer from the Yankees for duty as a reserve outfielder, but his desire to play regularly was so great that he signed with Washington instead, even though the offer was not as lucrative.

WHEN THE BABE CAME HOME IN 1919

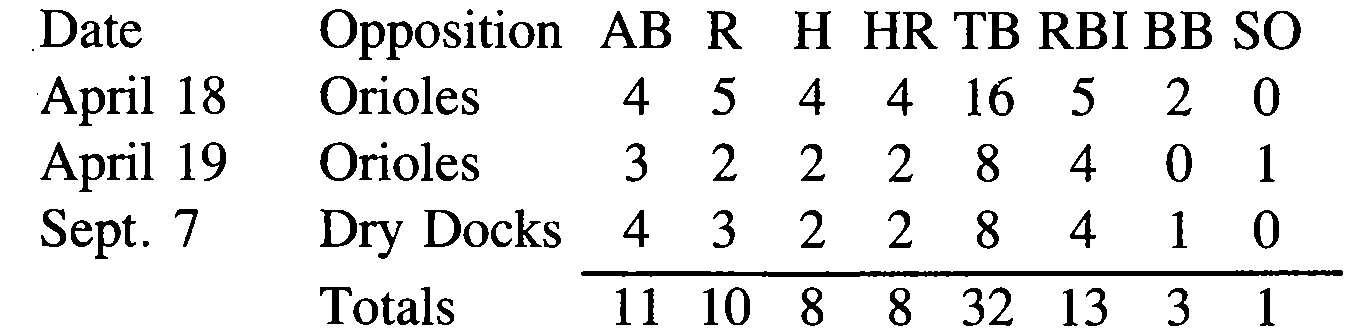

The year 1919 was the turning point in Babe Ruth’s career. His transition from outstanding pitcher to major league slugger par excellence was complete as he broke all existing big league records by hitting 29 home runs for the Boston Red Sox. During that season of 1919 Ruth had a chance to play three exhibition games in his home town of Baltimore – two against the International League Orioles, who would win the first of their seven consecutive pennants that year, and the other against the Baltimore Dry Docks, one of the best independent teams in the country. During the 1918 and 1919 seasons, the Dry Docks, managed by former major league pitcher Sam Frock, had at times such personnel as Johnny Bates, Fritz Maisel, Lefty Russell, Dave Danforth, Frank Schulte, Bucky Harris and Waite Hoyt.

The two exhibitions against the Orioles were played at Oriole Park just before the opening of the season on April 18 and 19. In the initial contest the Babe was in the left field and all he did was hit four consecutive home runs, with two bases on balls mixed in, as the Red Sox won, 12-3. He hit one off

Allen Herbert, a southpaw, and three off Harry Frank, a righthander. After the game Jack Dunn, who had taken Ruth out of St. Mary’s Industrial School in 1914 and started him on his way, said he never saw such hitting and never expected to again. The following afternoon Ruth started as pitcher and batted in the ninth spot. He hit home runs on his first two times up to make it six’ in a row – the first off righthander Rube Parnham and one off portsider Rudy Kneisch. After he struck out against Kneisch on his third turn at bat, he retired for the afternoon as the Red Sox romped, 16-2.

The next time the Babe came to Baltimore and Oriole Park was on September 7 for the contest against the Dry Docks. Before the game Ruth, acting spokesman, presented the Dry Docks with a silver cup for winning the shipyard league championship. Then before a capacity crowd of more than 10,000, he went out and hit two home runs off Ed Flaherty, a righthander, as Boston won, 10-6.

The Babe’s terrific slugging before the home fans must have given him great satisfaction. His extraordinary display of power came not in the park where he made his 0. B. debut in 1914, but the one used by the Baltimore Federal League club in 1914-15 and known as Terrapin Park. It was the Federal League which forced Dunn to break up his outstanding minor league club in 1914, selling off his stars, including Ruth to the Red Sox, in mid-season. Moreover, Dunn was forced to move his team to Richmond in 1915. After the Federal League folded Dunn returned to Baltimore in 1916, bought Terrapin Park and renamed it Oriole Park.

Following is a recap of Ruth’s three games in Baltimore in 1919:

OUTFIELDER HAD THREE ASSISTS IN INNING

Many outfielders have made two assists in one inning in the major leagues, but Joe Sommer, outfielder for Baltimore in the American Association, once came through with three assists in one frame. It happened in a game against the New York Mets at Baltimore on August 9, 1887, all on throws to the plate on base hits, although one was dropped by the catcher for an error.

The game ended in a 10-10 tie, called after nine innings because of darkness. In the eighth inning, Paul Radford singled to left and went to second on an error by second baseman Sam Trott, a lefthanded thrower who spent most of his major league career as a catcher. Tom O’Brien singled to left field, and Sommer’s throw to the plate arrived in time, but catcher Lawrence Daniels muffed the ball. Dave Orr singled to left, and Sommer’s throw caught O’Brien trying to score. Frank Hankinson also got a hit to left, and once again Sommer’s throw was on the mark and Orr was nipped at home.

STIVETTS WON TWO COMPLETE GAMES IN DAY

Jack Stivetts spent just 11 years in the majors but still managed to win more than 200 games. His best year was in 1892 when he won 33 and lost 14 for the pennant-winning Boston National League club. He pitched a no-hitter that year on August 6, an 11-0 victory over Brooklyn, a feat he is duly credited with.

A month later, however, in a holiday attraction at Boston on September 5, he pitched and won morning and afternoon games against Louisville, but he is not included in the record books with pitchers who won two complete games in one day. In the morning game, Stivetts won, 2-1, in 11 innings, giving up only three hits, walking one, hitting one and fanning three. In the afternoon contest, Jack won, 5-2, on seven hits in nine innings, again giving up but one base on balls and striking out three.

SHORT PERFECTO FOLLOWED LONG RELIEF

When Rube Vickers pitched a five-inning perfect game for the Philadelphia Athletics at Washington on October 5, 1907, the last day of the season, he by no means put in a short workday. He retired all 15 Washington batters in the second game of a twin-bill, curtailed to five innings by darkness, after winning the first game in a long relief effort.

The first contest went 15 innings with the Athletics finally winning, 4-2. Charley Fritz started for the A’s and, after retiring the Senators in order for three innings, ran into trouble with a streak of wildness in the fourth. He walked Clyde Milan and Bob Ganley and hit Jim Delehanty to load the bases with none out. Rube Waddell came in and threw one pitch, which Bill Kay hit to center field for a Texas League single to score Milan. Waddell then stalked off the mound, and Vickers came in and retired the side without any further scoring. He pitched a total of 12 innings and gave up only eight hits and one run while walking two and striking out five.

For the afternoon, Vickers allowed just eight hits and no earned runs in 17 innings as he posted two victories. They were the only two games Vickers won for the A’s that year to go along with two defeats after joining the club late in the season.

For Fritz it was the only game he would pitch in the majors, and his record would show no hits and one run in three innings.

For Waddell there also was an ironic twist. The one pitch he threw that day was the last one he would make for the Athletics in a fabulous career in which he won 129 games for them in six seasons. During the winter Connie Mack peddled him to the St. Louis Browns.

LITTLE LEAGUERS OF 30 YEARS AGO

Thirty years ago Schenectady, N.Y., won the Little League world championship by defeating Colton, Calif., 7-5, on August 27, 1954. Two players on that championship team made the major leagues. Billy Connors, current pitching coach for the Chicago Cubs, was 0-2 in three seasons as a relief pitcher for the Cubs and New York Mets. Jim Barbieri played 39 games as an outfielder and pinch-hitter for the National League champion Los Angeles Dodgers in 1966, hitting .280. He made one appearance in the `66 World Series and was struck out by Moe Drabowsky. It was the first of Drabowsky’s record-tying six strikeouts in a row in a spectacular relief role in the first game of the Series at Los Angeles which sparked the Orioles to a four-game sweep while holding the Dodgers runless for the final 33 innings. The shortstop of the losing Colton team in the 1954 Little League series was Ken Hubbs, whose promising career with the Cubs was snuffed out after three years in an airplane accident on February 15, 1964. Hubbs set two major league records for errorless play in 1962, his rookie season.

On the way to the championship in 1954, Schenectady defeated the Lakeland, Fla., team, 16-0. The starting pitcher for Lakeland was John (Boog) Powell, who went to shortstop after being knocked out of the box. Powell played 17 years in the majors with Baltimore and Cleveland in the American

League and Los Angeles in the National and hit .266, with 339 home runs and 1187 RBIs. The catcher for Lakeland was Carl Taylor, Boog’s step-brother, who played six years in the majors with Pittsburgh and St. Louis in the National and Kansas City in the American. He batted .266, the same as Boog, with 10 homers and 115 RBIs while specializing as a handyman.

TWICE ONE OUT FROM NO-HITTER

Southpaw Bill Burns had an undistinguished career as a major league pitcher with a 27-48 record for five seasons with Washington, Chicago, and Detroit in the American League and Cincinnati and Philadelphia in the National.

Once in a while, however, he would perform like one of the best pitchers in the majors. In successive seasons — 1908 and 1909 he came within one out of pitching no-hitters.

On May 25, 1908, while hurling for Washington, Burns held the Tigers hitless until two out in the ninth inning when

Germany Schaefer singled to center. He lost the contest, 1-0, despite the one-hitter, but he would have lost even with the no-hitter because Detroit scored in the third inning on an error by Burns himself.

Then on July 31, 1909, again at Washington, Burns, this time pitching for the Chicago White Sox, hooked up in a duel with Walter Johnson in the first game of a doubleheader. Burns prevailed on this occasion, besting Johnson, 1-0, but once again was denied a no-hitter when Otis Clymer singled with two down in the ninth inning, and again Burns had to be content with a one-hitter. Ironically, Clymer did not enter the contest until the seventh inning, replacing George Browne, who was thrown out of the game by the umpire at the end of the sixth inning.

PINCH-HITTERS FOR SUPERSTARS

The years 1901, 1912 and 1927 were great seasons for superstars Nap Lajoie, Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth, respectively. Lajoie batted .422 in 1901, the highest batting average ever in the American League. In 1912, Cobb hit .410 for the Detroit Tigers, the second year in succession that he topped .400. In 1927, Yankee slugger Ruth hit 60 home runs, the first major leaguer to reach that plateau. Yet each of the superstars was pinch-hit for during his outstanding year mentioned previously.

On September 13, 1901, the Orioles beat the A’s, 12-10, at Baltimore. In the ninth inning, with the tying runs on base and two out, Doc Powers batted for Lajoie and flied to Mike Donlin to end the game. Why did Manager Connie Mack pinch-hit for Lajoie? It seems that the great batsman was sulking and refused to take his place at the bat.

On June 22, 1912, the Indians defeated the Tigers, 11-3, at Detroit. In the ninth inning Cobb was due at the plate but was nowhere in sight. George Mullin batted for him and ended the game by hitting into a force play. It turns out that after Cleveland batted in the ninth Cobb went to the clubhouse and was under the shower when he was due at the plate.

On April 12, 1927, the Yankees defeated the Athletics, 8-3, in the season’s opener at New York. In the bottom of the sixth inning Ruth told Manager Miller Huggins that he was sick and asked to be excused. Ben Paschal batted for him and singled. Ruth had fanned in two of his three previous times at bat against fireballer Lefty Grove.

CLEVELAND OVERCAME 15-RUN DEFICIT TO TIE

The most runs scored to overcome an opponent in a major league game is 12 and was accomplished twice in the American League – by the Detroit Tigers in 1911 and the Philadelphia Athletics in 1925. The National League record is 11 – by the St. Louis Cardinals in 1952 and the Philadelphia Phillies in 1976.

However, a game that was played at Cincinnati on September 30, 1894, the last day of the season, deserves special mention even though it does not qualify for this particular record. In a National League contest, Cleveland overcame a 15-run deficit to tie Cincinnati at 16-16, with the game being called at the end of the ninth inning because of darkness. The home team batted first and ran up a 16-1 lead after five and one-half innings, but Cleveland rallied for 15 runs, including 11 in the seventh inning, while holding the Reds scoreless after the sixth inning.

The line score and batteries:

Cincinnati 4 0 8 0 0 4 0 0 0 – 16 17 7

Cleveland 1 0 0 0 0 2 11 1 1 16 17 8

Dwyer, Whitrock and Murphy; Cuppy and Zimmer.

LOUIS UNIONS MADE GREAT START IN `84

The Union Association operated only one season — in 1884 – with the St. Louis Unions easily winning the pennant as they completely dominated the circuit from beginning to end. Moreover, St. Louis made the greatest start in baseball history, winning its first 20 games for an all-time record.

Through games of July 3 that year, St. Louis had a record of 40 victories and only four defeats, a percentage of .909. The St. Louis followers, however, were in for a shock on July 4, for the Unions lost two games in, two different cities on that Independence Day 100 years ago. In the morning, in a game at Washington, the Nationals jumped all over them, 12-1. Then in the afternoon the club went to Baltimore and once again suffered defeat by the score of 12-10. It was the only victory that Baltimore, one of the better teams in the league, was able to register against St. Louis in 14 meetings.

PALMER GRAND-SLAM FREE AS ORIOLE

Jim Palmer finished his long career with the Orioles in 1984 with Hall of Fame credentials. He won 268 games and lost only 152 while posting 53 shutouts. Another statistic that Palmer can well be proud of is the one which saw him give up nary a grand-slam home run in 3,947 1/3 innings in 558 games over 19 seasons.

Palmer did allow one bases-loaded homer in the minors. In 1967, when he appeared through as a major league pitcher at the tender age of 21 because of back and shoulder problems, Baltimore sent him to Rochester, then managed by Earl Weaver, for rehabilitation. Weaver started Jim against Buffalo on July 1. The game was played at Niagara Falls, the first International League game ever played there. The contest was moved to that city because of disturbances on Buffalo’s east side. Palmer was staked to an early 7-0 advantage, which he helped along with a two-run single, but he could not survive the third inning when the Bisons reached him for five runs. The big blow was a home run with the bases full by 19-year-old Johnny Bench. Rochester, however, won the game, 10-8, with the victory going to Delano Hill.

KILLEBREW BROKE IN AS PINCH-RUNNER

Harmon Killebrew, whose 573 lifetime home runs propelled him into the Baseball Hall of Fame, made his major league debut as a pinch-runner. After signing a $30,000 bonus contract, 17-year-old Killebrew reported to the Senators in Chicago on June 22, 1954. The next afternoon Manager Bucky Harris sent Harmon into the game in the second inning as a pinch-runner for Clyde Vollmer, who had been hit by a pitched ball. The White Sox won the game, 8-6.

In his first five weeks with the Nats, Killebrew got into four games, each time as a pinch-runner. He then made two appearances as a pinch-hitter, grounding out each time. He finally received a chance to start a game at Philadelphia on August 23, exactly two months after his debut, in the second half of a twin-bill. He played second base and made the best of his opportunity, registering three hits, including a double, and two RBIs in four times at bat.

A year and a day after he appeared in his first game, Killebrew hit his first home run. It came in a game at Washington on the night of June 24, 1955, in which the Tigers swamped the Nats, 18-7. In the top of the fifth inning Killebrew was booed lustily when he booted Al Kaline’s grounder which allowed Bill Tuttle to score, increasing the Detroit lead to 13-0. But the jeers turned to cheers in the bottom of the frame when Harmon crushed a Billy Hoeft pitch into the distant left field stands. The ball landed 24 rows up in the bleachers where the base of the stands was 400 feet from the home plate. As a bonus player Killebrew could not be farmed out for two years and as a consequence rode the bench most of the time. Although it took a year for Killebrew to hit his first home run, in reality it came on only his twenty-ninth time at bat in the majors.

TOM BROOKSHIER HAD BRIEF FLING IN O.B.

Tom Brookshier, sometimes controversial but a top National Football League telecaster for CBS for many years, had a brief fling in Organized Baseball as a pitcher. Brookshier won seven decisions and lost only one for Roswell in the Class C Longhorn League in 1954.

The first baseman for the Roswell club was Joe Bauman, who set the home-run record for O.B. that year with 72.

Brookshier, then 22 years old, went into the Air Force for two years and when he finished his service commitment decided to go back to the Philadelphia Eagles, for whom he played in 1953, and concentrate on his pro football career.