From Mexico to Quebec: Baseball’s Forgotten Giants

This article was written by Bill Young

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Big Apple (New York, 2017)

1946

In 1946, 22 major leaguers—11 of whom were under contract to either the New York Giants or the Brooklyn Dodgers—bolted to Mexico in search of greener (baseball) fields.1 This article looks at the fate and fortunes of eight members from the 1945 New York Giants who left their New York counterparts to suit up with one of six teams in the Mexican League.

It is worth remembering that the year 1946 was unique in a variety of respects. The war was over, peace and freedom carried the day; military personnel, young men and women who had sacrificed so much, were returning home, including rafts of ball players itching to get back onto the diamond. According to one estimate, nearly a thousand big leaguers and 3,000 minor leaguers were expected to be demobilized by early 1946.2 Suddenly baseball was about to be fun again—except for those major or minor leaguers who were soon to become expendable as their roles were either turned over to more accomplished players, or were minimized due to some local grievance, usually related to money or matters of respect.

It is worth remembering that the year 1946 was unique in a variety of respects. The war was over, peace and freedom carried the day; military personnel, young men and women who had sacrificed so much, were returning home, including rafts of ball players itching to get back onto the diamond. According to one estimate, nearly a thousand big leaguers and 3,000 minor leaguers were expected to be demobilized by early 1946.2 Suddenly baseball was about to be fun again—except for those major or minor leaguers who were soon to become expendable as their roles were either turned over to more accomplished players, or were minimized due to some local grievance, usually related to money or matters of respect.

For several of them Mexico was the answer.

EIGHT MEN OUT

Mexico certainly was a tantalizing alternative. The Mexican League of the day was offering wealth and opportunity unheard of in major league circles, an opportunity too good to turn down. And as things turned out, it was everything but.

The agent provocateur behind this Latin explosion was Jorge Pasquel, a wealthy Mexican businessman. He was in search of major league players to help raise the profile of the Mexican League to major league level. Although his offers had been rejected by the likes of Ted Williams and Stan Musial, others more vulnerable were willing to take a chance.

Eight members of the war-time Giants were prime targets, beginning with the feisty Danny Gardella. An outfielder/first baseman in 1944 and 1945, his frequent spats with manager Mel Ott during spring training—mainly related to dissatisfaction regarding his $5,000 status quo salary—so frustrated Ott that he eventually booted Gardella off the team, leaving him without a contract.

Without hesitation, Gardella contacted Pasquel, already an acquaintance, offering to make the shift down south. In short order he signed for $8,000 (plus housing allowance), a tidy increase over the Giants offer.

Gardella suited up for Vera Cruz in 1946. But when he was prevented from playing in a game against the Negro Leagues Cleveland Buckeyes in New York the following year, he launched a suit against Major League Baseball, “charging conspiracy to restrain free trade and using the reserve clause to deprive him of his right to make a living. Jumpers Max Lanier, Fred Martin, and (Sal) Maglie filed a similar suit shortly thereafter.”3

Others following Gardella’s lead included pitchers Ace Adams and Harry Feldman, two right-handed hurlers whose six-year tenure with the Giants had produced a combined accumulated record of 76–68; 3.65.4 Both had such rocky starts in 1946 they side-stepped demotion to the minors by joining Gardella in Vera Cruz.

Seldom-used pitcher Adrian Zabala didn’t hesitate when offered $8000 to play for Puebla, plus a $7000 signing bonus. Nor did Cuban-born Nap Reyes, a solid infielder for the 1943–45 Giants, and a stalwart of the winter leagues. He remained in Puebla for three seasons before being traded to Mexico City in 1949.

Position players George Hausmann and Roy Zimmerman were especially vulnerable. Hausmann, a light-hitting, smooth-fielding second-baseman 1944–45, was aware his chances with the Giants in 1946 were slight. Rookie Zimmerman had played in only 27 games in 1945 and was dismissed when he sought a cost-of-living raise. Both elected to take the plunge. Hausmann signed first with Torreon, then Monterrey, while Zimmerman joined Nuevo Laredo.

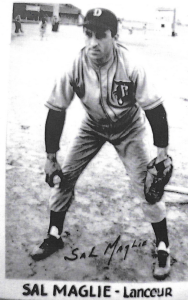

In a bizarre sense, their action influenced Sal Maglie’s decision to leave as well. When the duo had sought him out for advice, Giants owner Horace Stoneham assumed erroneously that Maglie was also planning to leave. Angered, the boss summarily “fired” all three, even though they had signed contracts. That rash action so infuriated Maglie that he immediately resolved to join the others and take his chances. Some have called this the best baseball decision he ever made. “I will make as much the first year, including my bonus, as I would in five years at my present rate with the Giants,” he said at the time.5

The three Brooklyn Dodgers who broke for Mexico were outfielder/third baseman Luis Olmo (only the second Puerto Rican to play in the big leagues), catcher Mickey Owen (he of the dropped third strike), and farmhand Roland Gladu of the Montreal Royals. Olmo remained in Mexico and Venezuela throughout the dark years; Owen’s southern sojourn was brief and unhappy, leaving him with no place to play; while Gladu returned to Quebec and built a new career as player, manager, and scout within the province.

SOUTH OF THE BORDER

In the spring of 1945, A.B. “Happy” Chandler—a former Senator and Governor of Kentucky—was named Commissioner of Baseball, filling the position left vacant following the death of long-time occupant, Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Never considered one of the titans of baseball, Chandler nevertheless was immediately faced with two unanticipated and delicate matters, both of which had a profound effect on the game and the men who played it.

In 1945 Brooklyn Dodgers’ President and General Manager Branch Rickey signed Negro Leagues infielder Jackie Robinson, formerly of the Kansas City Monarchs, to a contract with the Dodgers’ Triple-A farm club Montreal Royals, shattering the color barrier that had beclouded Organized Baseball throughout the twentieth century.

Chandler, in spite of pressure to do otherwise, chose not to interfere, allowing the matter to sort itself out in its own good time.

The other challenge was more complicated; how to deal with those major league players who had fled to Mexico. Here his action was swift and unbending, decreeing that all players who jumped their contracts or violated their reserve status were to be banished from baseball for five years, allowing that this ruling would not apply to players who returned to their teams by opening day.6

His rationale was clear. “The question was having the penalty severe enough so that it would deter fellas who might want to do the same thing for quick money…I just made it five years and stopped a whole lot of them.”7

For most of the exiles the experience was an unhappy one, and by 1948 almost all had returned to the United States, slightly wealthier but isolated and with no place to play. The Cardinals’ Max Lanier perhaps spoke for the majority when he told author Donald Honig, “Conditions down there weren’t too good. Half the time you were so sick you couldn’t play, you know problems with the water, the whole thing didn’t last very long. I stayed in Mexico about a year and a half… [Jorge] Pascal started cutting everybody. He cut me from $20,000 to $10,000. That’s when we started jumping back to the States.”8

Perhaps the two players with the fewest complaints were Reyes and Maglie. Both adapted readily to their circumstances: Reyes remained in Mexico for the duration, while Maglie learned the language and honed his pitching skills into a fine art. It was his great good fortune to play for Puebla under manager Dolf Luque, a former Giants pitching coach and pilot of Maglie’s winter Cuban League team.

“Whatever I am as a pitcher,” Maglie said in 1956, “I owe to a great extent to Adolfo Luque, the most accomplished teacher of mound techniques the game has seen.”9 Indeed, as Marshall noted: “Maglie developed an outstanding slider by throwing his curve like a fast ball and went on to win twenty games in each of his two seasons [in Mexico].”10

A LOST YEAR

As previously mentioned, by 1948 most of the jumpers had returned home only to learn that baseball’s doors were firmly closed to them. Not only was the five-year ban still in effect, the commissioner had now specified that if any of the jumpers surreptitiously played for minor league or other low-level clubs they would be suspended for life.

Left with few choices, Max Lanier formed the Max Lanier All-Stars, a travelling collection of players still considered personae non gratae. They included five New York Giants: pitchers Feldman and Maglie, infielders Hausmann and Zimmerman, and outfielder Danny Gardella. Missing were Adams (retired), Reyes (Mexico), and Zabala (Sherbrooke).

Left with few choices, Max Lanier formed the Max Lanier All-Stars, a travelling collection of players still considered personae non gratae. They included five New York Giants: pitchers Feldman and Maglie, infielders Hausmann and Zimmerman, and outfielder Danny Gardella. Missing were Adams (retired), Reyes (Mexico), and Zabala (Sherbrooke).

Lanier recalls: “We went on the road and played about 80 ball games against college and semi-pro teams…But do you know, we got to where we couldn’t get a ball game…We knew we couldn’t play in professional ballparks against professional ballplayers but [Chandler] shouldn’t have tried to stop us from playing against colleges and semi-pro clubs. But he did.”11

The team mostly circulated through the South and Midwest, bouncing along in a Trailways Bus emblazoned with the words: “MAX LANIER’S ALL STARS.” But they ran out of places to play. Resigned to pumping gas in hometown Niagara Falls, Maglie counted this period among the darkest of his life.12

REDEMPTION

In 1948, while the Max Lanier All-Stars were traveling cross country, two other jumpers—Gladu and Zabala—were in Quebec Province exploiting an untouched venue ready to welcome jumpers with impunity, and pay well for their efforts. Called the Provincial League, it was an independent circuit centered in the south-west corner of Quebec that paid homage to no one other than itself.

Long a fixture in the province, by 1948 the proudly autonomous and highly competitive loop was increasingly looking for accomplished players of any stripe. And jumpers were fair game. That spring Gladu was named player/manager of the Sherbrooke club. He knew that he and his counterparts could confidently play in the league, without fear of reprisal, simply because league authorities didn’t give a damn. They knew they were beyond censure.

Gladu convinced Zabala to sign with Sherbrooke, the region’s metropolis, where he put together a magnificent 18–8 record.13 Two other jumpers also joined that year: Bobby Estalella (St. Jean), who batted .374 with 27 home runs, and Danny Gardella (Drummondville) a late-season arrival.

If 1948 was prelude, 1949 was the real thing: the exiles’ moment of redemption. Various Quebec teams took on 12 of the original 22 jumpers, including five Giants: Feldman, Gardella, Maglie, Zabala, and Zimmerman.

Nevertheless, these twelve outliers comprised only a fraction of the newcomers discovering the league that year. In spite of—or perhaps because of—its informal status as an Outlaw League, a flood of top-notch talent poured in: young Latin players, veterans of the Negro leagues, wartime fill-ins, and gifted locals. Most fans believed at the time that a select team of Provincials could have defeated the Montreal Royals in a nine-inning game if ever given the opportunity.14

About the time the league celebrated Opening Day, Commissioner Chandler was growing increasingly troubled, as suits launched by Gardella, Lanier, Martin, and Maglie were coming before the courts. Gardella, still without a contract, was challenging the Reserve rule—that vulnerable bit of legislation binding a player to his club in perpetuity. Lanier and colleagues, having also registered grievances pertaining to “their right to earn a living,” now watched and waited. And equally worrisome for Chandler was the alarming possibility that the Provincial League’s success as an independent operation might soon serve as a harbinger for others to follow.

About the time the league celebrated Opening Day, Commissioner Chandler was growing increasingly troubled, as suits launched by Gardella, Lanier, Martin, and Maglie were coming before the courts. Gardella, still without a contract, was challenging the Reserve rule—that vulnerable bit of legislation binding a player to his club in perpetuity. Lanier and colleagues, having also registered grievances pertaining to “their right to earn a living,” now watched and waited. And equally worrisome for Chandler was the alarming possibility that the Provincial League’s success as an independent operation might soon serve as a harbinger for others to follow.

With all of these unsettling factors swirling above his desk, the Commissioner did the only thing he could. He lifted the five-year ban two years before it was to end.

As Marshal puts it: “On June 5, [Commissioner Chandler] announced that the jumpers’ bans were being reduced from five years to three and that, in spite of the pending suits against baseball, all of the jumpers were now free to return to the game.” Players were entitled to rejoin their clubs for a thirty-day trial period, at which time they would be kept, traded or released.15

Interestingly, although most of the jumpers chose to return immediately, a few did not. Of the forgotten Giants, Zabala and Feldman, neither enjoying a bumper strong start in 1949, were the only two to depart.16 Gardella, Maglie, and Zimmerman, teammates in Drummondville, elected to remain, determined to complete the season.

Zimmerman played 91 games that year, batting .245 with 22 home runs and 77 runs batted in, tops on the club. He started out in brilliant fashion, but as the season progressed, his numbers declined dramatically. The probable cause, according to Drummondville catcher Jerome Cotnoir, was an unknown illness, likely ulcers, that struck early in the summer and hampered his game for the rest of the year.17

Zimmerman played 91 games that year, batting .245 with 22 home runs and 77 runs batted in, tops on the club. He started out in brilliant fashion, but as the season progressed, his numbers declined dramatically. The probable cause, according to Drummondville catcher Jerome Cotnoir, was an unknown illness, likely ulcers, that struck early in the summer and hampered his game for the rest of the year.17

Gardella was clearly the fan favorite. An unusual soul prone to pranks and outrageous actions, he had a good year both off and on the field, batting .281 with 15 home runs and 59 RBIs. “He would sometimes do a double flip and land right on the plate after a home run,” remembers Cotnoir. “Another time he began his home-run trot—by running backwards.”18

Maglie was the most determined and talented of the three. When asked why he remained behind, he gave several reasons. Partly, it was the money, less than the Giants were offering. Partly, it was conditioning. But mainly it was principle. As he told Cotnoir, “I jumped a team once; I’m not about to do it again.”19

The season ended well for the Cubs, nicely positioned in first place. They made it to the league finals, a 5 of 9 affair where their opponent was the Farnham Pirates, staffed mostly by Negro Leagues imports. Their heavy hitters were Joe Adkins, future major-leaguer Dave Pope and his pitching-brother Willie—and they were determined to win it all.

In the end, the Cubs were victorious although it took nine games to nail down the Championship trophy. Maglie added to the 18 games he won during the regular season with five more in the play-offs, including the grueling ninth game.

And with that, the up-and-down odyssey these Giant jumpers endured—from travels through Mexico and banishment, to Lanier’s Trailways bus, to redemption in Quebec’s Provincial League—came to a satisfying end. For it was here their suspensions were lifted, more than a year ahead of schedule, and at a time when this bunch of one-time Giants could still delight in the fun part of playing baseball, and make a bundle of money to boot.

POSTSCRIPT

Although the eight forgotten Giants were all invited back, little was offered them, apart from Sal Maglie. Ace Adams had retired after one year in Mexico. Harry Feldman settled for two years with the San Francisco Seals. George Hausmann played 16 games with the Giants before joining the Browns’ minor league system, playing through 1956. Nap Reyes, after one Giants’ at-bat, headed to Jersey City and several different teams through 1954. Adrian Zabala took his 15 games with the Giants in 1949 to the Giants’ and Braves’ minor leagues, remaining in organized ball until 1956. Roy Zimmerman retired after years with the Oakland Oaks (1950) and Tulsa (1951).

Although Danny Gardella had only one major league at-bat in 1949—before being sent down to Houston and released soon after, pretty well ending his high-minors career—he did come up the big winner on a different front. Major League Baseball, fearing that his legal action might ultimately jeopardize the Reserve Clause, offered to settle for $60,000. Gardella accepted the settlement and split the money with his lawyer.

But it was Sal Maglie who emerged the true star, amassing an enviable record of 119–62, 3.15, over 10 years. He appeared in three World Series, two with the Giants, losing to the Yankees in 1951 and sweeping Cleveland in 1954. In 1956, after being traded to Brooklyn, Maglie defeated Whitey Ford in the World Series opener before later finding himself on the back end of Don Larsen’s perfect game, losing 2–0 on five hits. Maglie stepped down in 1958 at age 41, the last of the Giants’ forgotten eight to play the game.

BILL YOUNG of Hudson, Quebec, is a retired academic administrator from Quebec’s Community College system. Throughout his life he has been fascinated by the game of baseball and its history, especially the baseball history of Quebec. In addition to numerous articles on this topic for SABR, seamheads.com, and other publications, he also co-authored (with colleague Danny Gallagher) two books on the Montreal Expos: “Remembering the Montreal Expos” (2005) and “Ecstasy to Agony: The 1994 Montreal Expos—How the Best Team in Baseball Ended Up in Washington Ten Years Later” (2013).

NOTES

1 According to Baseball Almanac, MLB’s 22 major league jumpers were Ace Adams, Giants; Alex Carrasquel, Senators; Bobby Estalella, Athletics; Harry Feldman, Giants; Moe Franklin, Tigers; Danny Gardella; Giants; Roland Gladu, Braves; Chile Gomez, Senators; George Hausmann, Giants; Red Hayworth, Browns; Chico Hernandez, Cubs; Lou Klein, Cardinals; Max Lanier, Cardinals; Sal Maglie, Giants; Fred Martin, Cardinals; Rene Monteagudo, Phillies; Luis Olmo, Dodgers; Roberto Ortiz, Senators; Mickey Owen, Dodgers; Nap Reyes, Giants; Adrian Zabala, Giants; Roy Zimmerman, Giants.

2 Lee Lowenfish and Tony Lupien, The Imperfect Diamond: The Story of Baseball’s Reserve System and the Men Who Fought to Change It (New York: Stein and Day, 1980), 125.

3 Charlie Weatherby, Danny Gardella, SABR BioProject: (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

4 Baseball-Reference.com: source of all statistical data unless otherwise noted.

5 William Marshall, Baseball’s Pivotal Era 1945–1951 (Lexington, Kentucky, The University Press of Kentucky, 1999), 53.

6 Ibid. 49.

7 Ibid.

8 Donald Honig, “Max Lanier Remembers,” The Armchair Book of Baseball II, ed. John Thorn (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1987), 184.

9 “Maglie taught how to pitch by Dolf Luque,” Daniel, Scripps-Howard staff writer, The Pittsburgh Press, September 24, 1956.

10 Marshal, 53.

11 Honig, 184.

12 Judith Testa, Sal Maglie: Baseball’s Demon Barber (DeKalb, Illinois, Northern Illinois University Press) 81.

13 All statistical information re: Quebec provided by statistician Christian Trudeau.

14 Drummondville starting eight, 1949: Quincy Trouppe, Roy Zimmerman, Stan Bréard, Roger Bréard, Joe Tuminelli, Roberto Vargas, Danny Gardella, Vic Pellot (Power).

15 Marshall, 244.

16 Author conversation with Jerome Cotnoir.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.