How Good Was the White Sox’ Pitching in the 1960s?

This article was written by Brendan Bingham

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in Chicago (2015)

The 1959 Chicago White Sox won the American League pennant despite a league-average offense. Under manager Al Lopez, the “Go-Go” Sox combined speed, fielding, and—especially—pitching to shatter the New York Yankees’ four-year run of AL championships.

The 1959 pitching staff was anchored by starters Early Wynn (age 39), Billy Pierce (32), and Dick Donovan (31). Abetted by relative youngster Bob Shaw (26), the 1959 rotation continued the solid pitching that had been the team’s staple during the 1950s. No additional AL pennants came the South Siders’ way in the decade ahead. Their closest finishes were one game back in 1964 and three games back, in fourth place, in 1967.

The absence of success, though, was no fault of the team’s run prevention abilities, as the White Sox strung together six straight seasons in the 1960s leading the AL in runs allowed per games (RA/G). 1

If the 1960 Sox’ pitching performance dropped off from 1959, it was a minor difference (Table 1). 2 In 1959, the Sox staff led the league in RA/G, earned run average (ERA), and adjusted ERA (ERA+) 3 and were second in walks and hits allowed per inning pitched (WHIP). The 1960 team was second in RA/G and third in ERA and ERA+. The drop off in 1961 was more pronounced, with near league-average team RA/G, ERA, and WHIP, but the start of as six-year run of AL-leading RA/G was only a season away.

The 1962 Sox pitching staff bore only a vague resemblance to the 1959 group. Wynn remained on board, but 1962 would be his last season with Chicago. Released after the season, he signed with Cleveland, where in limited action the next year he notched his 300 th win before retiring. Pierce had been sent to the San Francisco Giants after the 1961 season in a six-player trade. One arm received in return was Eddie Fisher, who would prove valuable through the 1965 season, mostly in a relief role. Donovan, left unprotected in the 1960 expansion draft, became the new Washington Senators’ best pitcher in their inaugural AL season. Shaw left for Kansas City during the 1961 season in an eight-player deal.

Along with Wynn, the 1962 Sox starters were Ray Herbert, Juan Pizarro, John Buzhardt, and Joe Horlen. The 32 year-old Herbert, who had arrived in the Shaw trade, enjoyed his only All-Star season in 1962, posting 20 wins and a 3.27 ERA. Pizarro, Buzhardt, and Horlen, key members of the pitching staff in the coming years, were all age 24 or 25. Pizarro had been acquired from the Braves before the 1961 season, Buzhardt from the Phillies before the 1962 season, and Horlen was home-grown, signed out of Oklahoma State University in 1959. In 1962, the young pitchers showed potential and inexperience. Sox starters were 58–64 with an ERA close to league average. It was the Sox’ bullpen that led the staff to 1962 season ERA and ERA+ close to the league’s best. Fisher and journeymen Turk Lown, Frank Baumann, and Dom Zanni posted a 3.22 relief ERA in more than 400 innings.

The Sox’ pitching improved in 1963 as the club led the AL in RA/G, ERA, and ERA+ and ranked second in WHIP. This improvement was attributable mainly to the maturation of the young starting corps. Pizarro, Buzhardt, and Horlen all improved on their previous years’ performance, although Buzhardt missed much of the second half with arm and shoulder problems, 4 and Horlen spent a short stint in the minors to regain his control and confidence. 5 The elder Herbert turned in another solid season, although not quite to the level of his 1962 campaign.

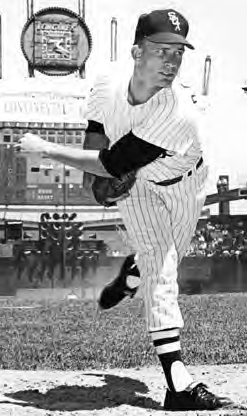

Wynn’s departure before the 1963 season made the White Sox pitching staff’s turnover from 1959 complete, but the quality of the mound work was not compromised. Wynn’s absence left an opening in the starting rotation for rookie Gary Peters, whom the Sox had signed in 1956 out of high school, where he had been a first baseman and outfielder and had done only a small amount of pitching. Peters was signed for his hitting, but shifted to the mound once he was in the White Sox system. 6 The Sox gave him his first taste of major-league ball in 1959, but until 1963 limited his major-league service. The timing proved right, as Peters’ 19–8 record and league-leading 2.33 ERA earned him the AL Rookie of the Year Award. Peters remained a cornerstone of the Sox starting rotation through 1969, and throughout his career hit well enough that he was called on to pinch-hit on occasion.

Southpaw Gary Peters, the Sox’ ace in the mid-1960s, led the AL in ERA in 1963 and 1966 and victories in 1964.

Another change the Sox made for 1963 paid dividends for the next six seasons. The White Sox sent the left side of their infield—shortstop Luis Aparicio and third baseman Al Smith—to Baltimore in exchange for infielders Ron Hansen and Pete Ward, outfielder Dave Nicholson, and pitcher Hoyt Wilhelm. Relief specialist Wilhelm had been a selection to the AL All-Star team three of his four seasons in Baltimore, but by baseball standards was considered old in 1963. (When he joined the White Sox, Wilhelm claimed to be 39. In fact, he was 40, according to the birth certificate found following his death in 2002. That document showed him to have been born in 1922, not 1923 as previously believed. 7 )

Age aside, Wilhelm took charge of the Sox bullpen, leading the relief corps in innings pitched in 1963. He was the Sox’ most effective reliever, as measured by ERA, from 1964 through 1968 and did not retire until 1972, evidence that age is not the most critical criterion by which to judge a knuckleball-throwing reliever.

The White Sox’ pitching staff remained largely the same in 1964. The most noteworthy newcomer was 21-year-old Bruce Howard, of Villanova University, 8 who got three starts. Howard remained a solid contributor to the staff as a starter and reliever through 1967. With Sox starters accounting for 73 wins and 47 losses with a 2.65 ERA, the team went deep in the pennant race in 1964, unlike in the preceding seasons. In the effort to compete with the Yankees and Orioles, manager Lopez and pitching coach Ray Berres went with a three-man rotation in the closing weeks of the season, with Peters, Pizarro, and Horlen bearing the burden as starters. Meanwhile, the bullpen had its work horses, too, with Wilhelm accruing more than a third of the team’s relief innings and fellow knuckleballer Fisher contributing nearly as many. The Yankees prevailed in the pennant race, but Chicago’s stout moundsmen topped the AL in RA/G, ERA, ERA+, and WHIP.

A somewhat different and less dominant cast of starting pitchers appeared in 1965. Howard’s role expanded while Pizarro’s was limited by injuries. One off-season trade sent Herbert away, and another, a three-team deal among Chicago, Cleveland, and Kansas City, brought 21-year-old southpaw Tommy John to the White Sox. In aggregate, the starters put up a 62–48 mark and a 3.24 ERA—good but not brilliant. The bullpen, however, was as strong as ever, posting a 2.54 ERA in 518 1/3 innings. The main relief men were Wilhelm, Fisher, and Bob Locker, a 27-year-old rookie, whose history included a college career at Iowa State and two years in the military. 9 Despite the late start, Locker spent ten years as a reliable relief man with four MLB teams. In total, the 1965 staff combined a league-leading WHIP and an ERA just a tick below the league lead.

Lopez retired after the 1965 season, bringing to a close his nine campaigns as Sox manager (he returned to helm the team for three short stints beginning in July 1968). New manager Eddie Stanky set a starting rotation of Horlen, Peters, John, and Buzhardt in 1966. Howard also earned some starts, especially late in the season when Buzhardt was dropped from the rotation. 10 Pizarro, again slowed by injuries, 11 pitched in relief when available. Wilhelm remained the team’s most valuable reliever, but in 1966 he pitched fewer innings than in his previous seasons in Chicago. Meanwhile, Locker contributed another strong season in relief, while Fisher was traded in mid-June. The bulk of the remaining relief innings went to rookie Dennis Higgins.

In all, the 1966 White Sox pitching staff equaled the 1964 staff, leading the AL in RA/G, ERA, WHIP, and ERA+, accomplishments due in large part to Peters’ performance—he paced the league with a 1.98 ERA.

At the start of the 1967 season, there were no changes to the Sox rotation, but Buzhardt contributed just seven starts before losing his starting job. Previously known for his ability to locate his pitches, Buzhardt began to struggle with his control, causing Stanky to puzzle over how best to use the right-hander. A watershed moment came in mid-June when Buzhardt was called on in relief in an extra-inning game. He pitched very effectively in what turned out to be an eight-inning relief appearance, but took a frustrating loss against the Senators in the 22 nd inning. He started only one more game for the Sox before being sold to Baltimore before the season’s end, and was finished as a major league pitcher after the following season. 12

Prior to the season, Pizarro had been traded to Pittsburgh in exchange for Wilbur Wood, another knuckleballer. Mostly a relief contributor in 1967, the 25-year-old Wood showed signs of the talent that would make him the Sox’ most celebrated pitcher of the 1970s. Once again in 1967, the Sox led the league in RA/G, ERA, WHIP, and ERA+, but the team’s poor attack doomed it to a heartbreaking fourth-place finish.

The Sox’ six-year run of AL-leading RA/G came to a close in 1968—Chicago’s 3.25 RA/G ranked fifth in the 10-team league. From the perspective of White Sox fans, the 1968 season (in which the club finished 67–95) is more noteworthy for what might have been. AL MVP and Cy Young Award winner Denny McLain had once been White Sox property. Chicago had drafted the flamboyant Illinois native out of high school, but after one year in the Sox minor league system, McLain was left unprotected and was claimed by the Tigers. 13

In 1969, the White Sox’ pitching was mediocre. Their RA/G, ERA, WHIP, and ERA+ all fell to worse than league average. The starting corps still included Horlen, Peters, and John, who combined for 100 starts, but only John reached his previous level. Wood was a strong contributor from the bullpen, but Locker was not. Wilhelm had been left unprotected in the off-season expansion draft and chosen by the Kansas City Royals. In hopes of bolstering the team’s rotation, the Sox dealt Locker to the Seattle Pilots in June for Gary Bell, who as a member of the Red Sox the year before had earned a place on the AL All-Star team. Unfortunately, Bell had lost his fastball 14 and was soon finished.

Joe Horlen, known early in his career by his formal name Joel, finished second in the 1967 AL Cy Young voting after leading the league in ERA and shutouts and firing a no-hitter.

Sadly for Sox fans, mediocrity would have been a pleasant alternative to the reality of the 1970 White Sox staff, the worst in the AL by all measures. The 1960s had passed, and gone too was Chicago’s standing as a dominant AL pitching staff.

Any enthusiasm for the gaudy stats piled up by White Sox pitchers in the 1960s must be tempered by consideration of park effects. Comiskey Park (known as White Sox Park from 1962–1975) was always a renowned haven for pitchers, even when the outfield fence was moved in. 15, 16

The extent to which Comiskey Park influenced run production in the mid-1960s can be seen in the White Sox’ home and road batting splits from 1962–1967 (Table 2), 17 a span in which the Sox scored runs near the league average on the road but not at home. The Sox scored more on the road than at home in all seasons but 1963; for the six years, their road scoring was nearly half a run per game (R/G) higher.

Meanwhile, the other nine AL teams combined for 0.2 R/G more at home, an indication that Comiskey was an extreme run-suppressing environment. The Sox certainly showed diminished power at home; their home slugging percentage (SLG) lagged behind their road SLG and the league norm, while their on-base percentage (OBP) was similar at home and away and similar to other teams’ road OBP.

If Comiskey Park negatively impacted the Sox’ run production, it also must have affected the opponents’ ability to score, thus distorting the Sox’ pitching statistics in the process. Traditional pitching statistics tallied at Comiskey Park demand proper context. One way to adjust for park effects on pitching is through adjusted statistics, such as ERA+ in place of ERA. Another way is limiting one’s analysis to performance in road games. The advantage of focusing on road splits is that the analysis can be applied to any pitching statistic, not just ERA, while a downside is that half a team’s performance is ignored. In addition, when comparing two teams’ road efforts, the park effects are actually reversed, albeit in a strongly dampened way. For example, during the 10-team era of the 1960s, Sox opponents each played one-ninth of their road games at pitcher-friendly Comiskey Park, while the Sox played all their road games elsewhere.

Table 3 shows road splits for three statistics (RA, ERA, and WHIP) for AL teams from 1962 through 1967.18 The road White Sox outpitched the road Yankees in two of New York’s league championship seasons (1962 and 1963) and put up very similar road pitching numbers in the Yankees’ other pennant season (1964), but these early 1960s Bronx teams of Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, and Elston Howard relied more on bats than pitching to win. Whether the Sox had the best road pitching performance in any of these years is another matter. In 1962, the White Sox, Tigers, Twins, and Angels produced similarly strong road pitching numbers. The White Sox can lay claim to having had the best road pitching in the AL in 1963, as evidenced by league leading RA, ERA, and WHIP in road games. In 1964, the three teams that vied for the pennant also had the best road pitching splits.

A different team won the AL championship in 1965, 1966, and 1967. In 1965, the AL champion Minnesota Twins had the best road WHIP and second-best road RA/G and ERA. The Twins’ road splits are almost indistinguishable from those of the Baltimore Orioles, but both teams clearly outperformed the White Sox’ pitchers on the road. In 1966, the Sox’ road pitching splits were better than those of the pennant-winning Orioles, albeit narrowly, but other than WHIP, the Sox road pitching splits were not especially close to those of the league-leading Twins. In 1967, the White Sox’ road splits for RA/G and ERA were only narrowly second-best to those of the pennant-winning Boston Red Sox, while the White Sox’ road WHIP was the AL’s fourth best.

Adjustment for park effects can reveal traditional statistics misrepresenting a team’s standing among its competitors. By analysis of road splits, the Sox’ pitching staff was shoulder-to-shoulder with the league’s best from 1962–1964, slipped noticeably in 1965, and hovered near second-best in 1966–1967.

This provides strong evidence that Comiskey Park’s vast dimensions likely contributed to Chicago’s run of league leading RA/G, not surprising given the inequity in the Sox’ own home/road batting splits during the same period.

ERA+ paints a similar picture. The Sox topped the AL in this stat in four of the six seasons in the 1960s in which they led the AL in RA/G (1963, 1964, 1966, and 1967).

Comiskey Park exaggerates how good the Sox’ pitching was, but cannot be accused of telling an outright lie. Playing in a pitcher-friendly home park contributed to the Sox’ ability to keep their opponents from scoring runs, with 1965 as the clearest example of how an extreme pitchers’ park distorts traditional statistics. Even after park adjustment, though, there is no denying that the White Sox mid-1960s pitching was consistently strong. The moundsmen simply had the misfortune of being paired with a batting attack that never rose above the AL’s midrange. The White Sox simply could not duplicate the unlikely recipe for success in 1959—ordinary offense coupled with extraordinary pitching—during the 1960s.

BRENDAN BINGHAM, a SABR member since 2009, has contributed to SABR publications “Bridging Two Dynasties: The 1947 Yankees” (2013) and “The National Pastime: Baseball in the Space Age” (2014). He was also a poster presenter at SABR 43.

Notes

-

Season and game statistics are from tabled values in http://www.baseball-reference.com/ and http://www.retrosheet.org/, accessed various dates November 15, 2014 through January 3, 2015.

-

RA/G, ERA, WHIP and ERA+ per tabled values in http://www.baseball-reference.com/, league splits pages.

-

ERA+ = 100*[lgERA/ERA] adjusted to ballpark.

-

John Gabcik, SABR Baseball Biography Project, John Buzhardt, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bd9d9a78, accessed November 29, 2014.

-

Gregory H. Wolf, SABR Baseball Biography Project, Joe Horlen, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/968eb078, accessed November 29, 2014.

-

Mark Armour, SABR Baseball Biography Project, Gary Peters, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/28c24b41, accessed November 29, 2014.

-

Mark Armour, SABR Baseball Biography Project, Hoyt Wilhelm, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/635428bb, accessed November 29, 2014.

-

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, Bruce Howard (baseball), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bruce_Howard_(baseball), accessed December 30, 2014.

-

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, Bob Locker, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bob_Locker, accessed December 30, 2014.

-

John Gabcik, SABR Baseball Biography Project, John Buzhardt, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bd9d9a78, accessed November 29, 2014.

-

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, Juan Pizarro (baseball), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_Pizarro_(baseball), accessed December 10, 2014.

-

John Gabcik, SABR Baseball Biography Project, John Buzhardt, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bd9d9a78, accessed November 29, 2014.

-

Mark Armour, SABR Baseball Biography Project, Denny McLain, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/6bddedd4, accessed December 10, 2014.

-

Cecilia Tan, SABR Baseball Biography Project, Gary Bell, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/33810d5c, accessed January 2, 2015.

-

Comiskey Park historical analysis, http://www.baseball-almanac.com/stadium/stadiumi.shtml, accessed December 10, 2014.

-

Curt Smith, SABR Baseball Biography Project, Comiskey Park (Chicago), http://sabr.org/bioproj/park/e584db9f, accessed December 10, 2014.

-

White Sox batting splits are from tabled values in http://www.baseball-reference.com/, team batting splits pages; batting splits for the set of other AL teams are calculated from tabled values in http://www.baseball-reference.com/, league batting splits pages and White Sox team batting splits; six-year averages are not weighted by unequal year-to-year values in plate appearances, at bats, and games played.

-

RA/G values are calculated from tabled RA values in http://www.baseball-reference.com/, team pitching splits pages; ERA and WHIP are per tabled values in http://www.baseball-reference.com/, team pitching splits pages.