How The Devil Rays Came to Tampa Bay

This article was written by Peter M. Gordon

This article was published in Time For Expansion Baseball (2018)

“If there’s a greater day in the history of Tampa Bay, I don’t know what it is,” proclaimed Tampa Bay Devil Rays principal owner Vince Naimoli on March 20, 1995, the day the American League awarded a franchise to the group he headed.1 After many years of city leaders striving to bring a team to the Tampa Bay area, Naimoli’s group had finally achieved that goal.

“If there’s a greater day in the history of Tampa Bay, I don’t know what it is,” proclaimed Tampa Bay Devil Rays principal owner Vince Naimoli on March 20, 1995, the day the American League awarded a franchise to the group he headed.1 After many years of city leaders striving to bring a team to the Tampa Bay area, Naimoli’s group had finally achieved that goal.

Naimoli led the ownership group, but it was a community effort. After they received the official word, an editorial in the St. Petersburg Times said that St. Petersburg City Administrator Rick Dodge “should get a medal for fifteen years of thankless diligence quest to bring a major-league franchise to the area.”2 Major League Baseball rebuffed seven different attempts from various groups during those 15 years before finally awarding a franchise in 1995 to begin play in 1998.

Although the quest to bring a major-league franchise to the Tampa Bay area intensified in the early 1980s, it is not an exaggeration to say that it started at the turn of the twentieth century. Tampa Bay is a large harbor on the Florida Gulf Coast a little more than halfway down the length of the state. There is no city named Tampa Bay; the “Tampa Bay” in the names of sports franchises like the Rays, Buccaneers (football), and Lightning (hockey), mean they represent the geographic area and municipalities surrounding the Bay.

The two largest cities are Tampa, at the northeast extreme end of the bay, and St. Petersburg, on the southeast corner, bordered on the west by the Gulf of Mexico and on the south and east by Tampa Bay. Tampa is in Hillsborough County, and St. Petersburg is in Pinellas County. The municipalities in the area do cooperate on several projects, but in the case of the Devil Rays, the local effort to bring major-league baseball to the area started in St. Petersburg in the early twentieth century. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, St. Petersburg city officials, managers, and St. Petersburg Times publisher Jack Lang kept the dream of a major-league franchise alive. This leadership is one of the main reasons why Tampa Bay’s major-league baseball franchise had its stadium in St. Petersburg.

St. Petersburg supported semipro baseball since its founding in the late nineteenth century. The semipro St. Petersburg Saints started regular play in 1902, and major-league teams began to play exhibition games in the area a few years later. In 1914 the St. Louis Browns, managed by Branch Rickey, became the first team to hold spring training in St. Petersburg. The Browns and Cubs played the first game between two major-league teams in the city. (The Cubs won, 3-2.) Either the financial arrangements or the competition wasn’t to the Browns’ liking, because they decided to train elsewhere in 1914.3

That might have been all for spring training in the area but for the efforts of one of the city’s most prominent citizens, Al Lang. Lang had moved to St. Petersburg from Pittsburgh in 1910. His networking skills enabled him to rise through the city’s political structure so quickly that by 1916 Lang was elected mayor. One of his endearing qualities for his fellow citizens was his effort to attract major-league teams to town. Once the Browns left, Lang persuaded the Phillies to train in St. Petersburg for the 1915 season. After the Phillies, led by Grover Cleveland Alexander and Gavvy Cravath, won the 1915 National League pennant, they trained in the city for the next three years.

For the next 70 years St. Petersburg was seldom without one, and sometimes two, baseball teams during spring training. During the 1940s one of the spring-training ballparks was named Al Lang Field in his honor. Games are still played there today.4

While Lang pushed to keep spring training in St. Petersburg, the dream of a major-league franchise seemed impossible. There had only been 16 major-league franchises since the turn of the twentieth century. When the leagues expanded in 1961 and 1962, they awarded franchises in the Northeast and Southwest and on the West Coast. Florida’s growing population supported spring training, but other cities got the prize.

In 1976 the NFL awarded the city of Tampa the expansion franchise that became the Buccaneers. The Bucs won the Super Bowl in January 2003, bringing the Tampa area its first major sports championship. The NHL Tampa Bay Lightning won the Stanley Cup in 2004. After the Bucs began playing, St. Petersburg Times publisher Jack Lake became a strong booster in editorials for a major-league-baseball franchise. Partly due to Lake’s efforts, in 1983 a group of local businessmen formed the Tampa Bay Baseball Group (TBBG) to coordinate efforts to bring a major-league franchise to the area.5

One of the first teams the group approached was the Minnesota Twins. Calvin Griffith, whose family had owned the franchise since it was the Washington Senators, made his living from the team’s profits. The Twins moved to the indoor Metrodome in 1982 but had an escape clause in their lease that they could trigger if the team failed to draw 800,000 fans in two of three seasons between 1982 and 1984. Twins attendance was over 900,000 in 1982 and over 800,000 in 1983. Nothing came of the discussions.

A pattern would soon emerge: A club that needed a new ballpark would dangle the fat wallets of the TBBG in front of city councils and state legislatures reluctant to approve new funding, in the hope that the competition would lead to more funding.

In 1985 TBBG approached the Oakland A’s, only to find the team’s interest wane as soon as the city provided upgrades to the Oakland Coliseum. Some cities would not commit to funding a ballpark until they had a team, but the St. Petersburg City Council thought it would help land a team if the city built the ballpark first. In 1985 the City Council appropriated $85 million to build a domed stadium. Its projected cost soon rose to $138 million. Commissioner Peter Ueberroth advised against building a ballpark on speculation, but the City Council decided to proceed.6

To demonstrate that local commitment went beyond the City Council, 20,000 fans pledged $50 each for seat licenses in the still-unbuilt ballpark. The city broke ground for the ballpark in 1986. As soon as it started to take shape, baseball owners and executives toured it.

In 1988 the Tampa Bay Baseball Group tried to buy the Chicago White Sox, who had failed to receive funding for a new ballpark. The threat of a move to Tampa Bay led Illinois’ governor, Big Jim Thompson, to literally stop the clocks in the Illinois State Assembly to keep the legislature in session until it approved a stadium funding bill.

In 1988 the Tampa Bay Baseball Group tried to buy the Chicago White Sox, who had failed to receive funding for a new ballpark. The threat of a move to Tampa Bay led Illinois’ governor, Big Jim Thompson, to literally stop the clocks in the Illinois State Assembly to keep the legislature in session until it approved a stadium funding bill.

The new Florida Suncoast Dome opened for business in 1990. The building soon got the nickname The Thunderdome, because its first major tenant was the NHL Tampa Bay Lightning. A baseball team remained elusive, but not for lack of trying. In 1990 the TBBG made a bid to buy the Kansas City Royals, but in the end the Royals received more support from Kansas City and decided to stay. The TBBG also made a strong bid to receive one of the new baseball expansion franchises awarded in 1991 to start play in 1993, but Major League Baseball awarded a franchise instead to a group from Miami led by Wayne Huizenga.

In 1992, local businessman and turnaround artist Vince Naimoli became the leader of the the Tampa Bay Baseball Group. Naimoli made his fortune buying money-losing companies, restructuring them, and turning them into profitable enterprises. If he couldn’t make them profitable, he would sell the assets for as much as he could get. He was used to pushing hard to get what he wanted and persuading people to go along with his plans. After the city of San Francisco turned down the Giants’ request for a new ballpark to replace cold, windy Candlestick Park, Naimoli agreed to buy the Giants for $115 million and move them to Tampa. It appeared that Tampa Bay’s long quest for a franchise was finally over.

With the loss of the Giants staring them in the face, San Francisco city leaders pledged to fund a new ballpark to keep the team. National League President Bill White joined the last-minute effort to keep the Giants and found a San Francisco group led by Peter Magowan to buy the team for $100 million, or $15 million less than Naimoli offered. The Giants and the National League accepted the lower bid, the team stayed in San Francisco, and plays in the privately financed ballpark now known as AT&T Park.

Naimoli and other local leaders sued the major leagues for interfering in this transaction. In a move that was perhaps even more threatening to baseball’s business, Florida Senator Connie Mack III, grandson of the legendary baseball manager and owner, and St. Petersburg Congressman C.W. Bill Young, started congressional investigations into whether it remained in the public interest for baseball to retain its antitrust exemption.

In March 1995, baseball owners approved two new franchises, one in Arizona and one, finally, in the Tampa Bay area to the group headed by Naimoli. Soon after the announcement was made, Mack and Young ended their investigations. Naimoli wanted to call the team the Sting Rays, but found there was a winter-league team in Hawaii that owned the name. Rather than purchase the name from that team, Naimoli decided to call the team the Devil Rays. That caused so much controversy that the team commissioned a poll to prove that the fans accepted the name change.7 The team did not have a winning season until it dropped “Devil” to become the Rays in 2008.

In July 1995 Naimoli named Chuck LaMar the Devil Rays’ first general manager. He worked for several successful organizations during the 1980s and 1990s, including the Reds, Pirates, and Braves in scouting and player development. LaMar had never worked as a general manager, and he was now starting one of the most difficult jobs a general manager could have.

LaMar planned to build the team through young players and the draft, with a plan to contend in five to seven years. Naimoli, who made his fortune quickly turning around companies, did not have the same patience. When it came to conflicts between the owner and his first-time general manager, the owner would usually get his way.

On September 26 LaMar signed the team’s first player, Adam Sisk, a 6-foot-4 right-handed pitcher from Edison Community College in Fort Myers, Florida. Sisk would never pitch in the majors, but it was a start. In November the Devil Rays unveiled their new uniforms.

In 1996 Paul Wilder, an outfielder and first baseman, became the team’s first draft pick during the amateur draft held on June 4. The Rays stocked their farm system with 97 players, which was the fifth-highest total in draft history to that time. The Gulf Coast Rays began to play that summer when right-hander Pablo Ortega threw the first pitch in club history — a ball.

On October 3, 1996, the Rays announced the sale of ballpark naming rights to Tropicana, a relationship that still existed in 2018. In January of 1997, the major-league owners voted to put the new franchise into the American League, adding it to what was arguably the most competitive division in baseball, the American League East. The Devil Rays would struggle for years to compete with the deep-pocketed New York, Boston, Toronto, and Baltimore franchises.

Throughout 1997 Naimoli and LaMar continued to add minor-league teams, players, and staff. The player evaluation team scouted major-league players likely to be available in the November 18 expansion draft. On November 7, the Devil Rays hired Larry Rothschild to be their first manager. Rothschild, the Florida Marlins’ pitching coach, had never managed before, and returned to coaching after his turn at the Rays’ helm.

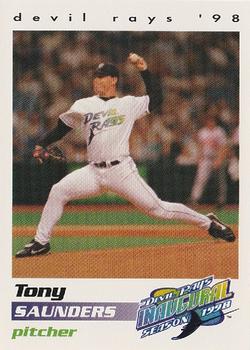

The Devil Rays’ inexperienced leadership continued to learn on the job throughout the expansion draft. On draft day, the National League expansion Diamondbacks picked first. LaMar’s first draft pick was left-handed pitcher Tony Saunders from the Florida Marlins. The 24-year-old started regularly for the team during its freshman year, finished with a won-lost record of 6-15, and led the league in walks with 111. As of 2018, Saunders still held the team record for most walks allowed in a season.

They picked Quinton McCracken second. He had a decent year in 1998, earning 2.1 WAR, and played in the majors for another eight years. The Devil Rays’ third pick was a gem: They plucked Bobby Abreu from the Houston system. Abreu earned 60 bWAR for his career and in 1998 hit .312/.409/.497 and slugged 17 home runs — for the Phillies.8

Chuck LaMar had arranged with the Phillies to trade Abreu for shortstop Kevin Stocker after the draft. Stocker was 28 in 1998 and had been solid if unspectacular for the Phillies for the previous five years. LaMar said the Rays needed a shortstop to help his pitchers, so he traded a player with a lifetime bWAR of 60 for one (Stocker) with a lifetime bWAR of 6, over half of which he had already earned. This trade was so lopsided that Rob Neyer wrote about it in his Big Book of Baseball Blunders.9

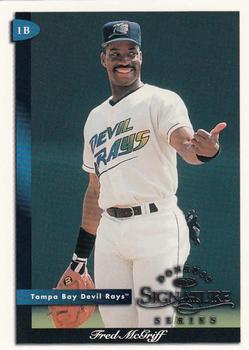

Vince Naimoli told his young general manager that it was imperative for the first-year team to lose fewer than 100 games. Consequently, after the Stocker trade, LaMar purchased the contract of slugger Fred McGriff from Atlanta, while trading shortstop Andy Sheets and pitcher Brian Boehringer to San Diego for backup catcher John Flaherty. LaMar also signed free-agent closer Roberto Hernandez, and gave up another solid pro when he traded the eighth pick, Dmitri Young, to the Reds to complete a deal for Mike Kelly.

Vince Naimoli told his young general manager that it was imperative for the first-year team to lose fewer than 100 games. Consequently, after the Stocker trade, LaMar purchased the contract of slugger Fred McGriff from Atlanta, while trading shortstop Andy Sheets and pitcher Brian Boehringer to San Diego for backup catcher John Flaherty. LaMar also signed free-agent closer Roberto Hernandez, and gave up another solid pro when he traded the eighth pick, Dmitri Young, to the Reds to complete a deal for Mike Kelly.

LaMar told USA Today Baseball Weekly after the draft, “We think we have a great combination of young players and experienced players. We’re going to try to be as competitive as we can, as quick as we can, and never lose sight of our long-term goals.”10

Other free agents the Rays signed before the start of the season included starter Rolando Arrojo ($170,000 plus $45,000 performance bonus), 40-year-old Wade Boggs (for $1.1 million and a $650,000 performance bonus), starter Wilson Alvarez (5 years, $35 million), and Dave Martinez (3 years, $4.5 million). None of these players were signed because they were building blocks for the future. In a pattern that would repeat throughout the Naimoli era, they were signed to make a bad team a little less awful. At least Martinez would contribute to the Rays as a bench coach after his playing career ended. These players were long gone when the Rays won their first pennant in 2008. As of 2018, Roberto Hernandez still held the franchise record for career saves, with 101.

Fans were still excited to have major-league baseball, and Opening Day tickets sold out in just 17 minutes. More than 2.4 million tickets were sold during the season. Perhaps the team’s veteran leadership helped the Devil Rays get off to a fast start. They opened their inaugural season on March 31, 1998, against the Detroit Tigers at Tropicana Field.

Four Hall of Famers with ties to the Tampa Bay area — Ted Williams, Stan Musial, Monte Irvin, and Al Lopez — each threw out a first ball on March 31. The Devil Rays Opening Day lineup was Quinton McCracken, CF, Miguel Cairo, 2B, Wade Boggs, 3B, Fred McGriff, 1B, Mike Kelly, LF, Paul Sorrento, DH, John Flaherty, C, Dave Martinez, RF, Kevin Stocker, SS. Wilson Alvarez was the starting pitcher. That lineup contained one future Hall of Famer (Boggs), one player whose career could be considered “Hall of Fame caliber” (McGriff), and several solid major leaguers.

In the first game the Tigers scored six runs and knocked out Alvarez in the second inning, going on to win, 11-6. Martinez got the first hit in Devil Rays history, a single in the third inning, and Wade Boggs hit the first home run, in the sixth inning. Boggs in 1999 became the first Ray to reach 3,000 hits. (Most of his hits came in a Boston Red Sox uniform.)

The next day, April 1, the Devil Rays recorded their first win, 11-8. Rolando Arrojo started, holding the Tigers to four runs through six innings to earn the win. He was aided by an 18-hit attack that included a home run by Rich Butler and a triple from Kevin Stocker. The expansion team took the series from the Tigers with a 7-1 win on April 2. Tony Saunders allowed a run in the first but held the Tigers scoreless for the next five innings. Esteban Yan replaced him at the start of the seventh inning, and got the win when the Devil Rays broke through with six runs in the bottom of the inning.

Tigers manager Buddy Bell said, “I don’t think they’re even close to being your typical expansion team. With the talent they have they are certainly better than expansion teams from the past.” Baseball pundits wrote articles saying the Devil Rays might break the win record for expansion teams, which was held by the 1961 Los Angeles Angels with 70.11

The Devil Rays got the first shutout in team history on April 5. Wilson Alvarez earned his first win, blanking the White Sox for 6⅔ innings, followed by Esteban Yan and Jim Mecir. Quinton McCracken and Miguel Cairo each got two hits. Cairo drove in two runs with a bases-loaded single. McGriff doubled in a run with two outs in the bottom of the fifth.

The Devil Rays continued their winning ways for the next couple of weeks. Roberto Hernandez earned the first of his 101 saves for the franchise on April 12. After beating the Angels on April 19, the team had a 10-6 record. No other expansion team in history reached four games over .500 at any time during its first year.12 On April 23 the team sported an 11-8 record. It’s a testament to the strength of the American League East in 1998 that this fine early performance put the Rays in fourth place in the division. The Yankees, at the top of the pack, were on their way to a 114-win season.

It looked as if the club’s investment in free agents was paying off. If all the veterans could find one more good year from somewhere, maybe the team could go all the way. Unfortunately for the fans, April 23 was the high point of the season. After their win that day, they lost 10 of their next 12 games.

Twenty years after their inaugural season the Rays brought several players to back Tropicana Field for a celebration, and several of them said they remembered 1998 as a year they became a family that competed hard to win every game.

Closer Roberto Hernandez said, “It was exciting … lots of emotions. Fans that came were outstanding. We tried to play hard, play to win, and leave everything out on the field. We gave it all.”13

Backup catcher Mike DeFelice said, “The Rays were one of the tightest knit teams I ever played on. At the end of the year we didn’t want to leave each other.”14

The Devil Rays did have some impressive wins amid all those losses. On May 12, 1998, in a day game at Tropicana Field, they beat the defending American League champion Cleveland Indians, 6-5 in 14 innings. The Rays took advantage of some Indians fielding mistakes to get out to a four-run lead in the bottom of the first. The Indians scored four during the middle innings to tie it up, and it looked over when Kenny Lofton tripled in the top of the 14th and came home on a fly ball by Manny Ramirez.

In the bottom of the 14th, Aaron Ledesma singled to right, and after an out, Kevin Stocker justified the team’s faith in him by hitting a walk-off, two-run homer.

The Devil Rays followed that win with two losses and then a four-game win streak that took them to third place, behind the Red Sox in second and the Yankees in first. That was as high as the team rose in 1998; the bottom was about to fall out.

The team lost steadily in June, July, and August. The Rays suffered a 10-game losing streak from late June to early July. At least on July 5 they contributed to baseball history when Randy Winn became Roger Clemens’ 3,000th strikeout victim in a 2-1 loss to the Toronto Blue Jays.

After they broke the streak with a 5-4 win against the Red Sox on July 14, the Devil Rays lost the next day, won on July 16, and dropped four more. They won only nine games in July, the fewest of any month that season. In August they won 10, against 20 losses. The team bounced back slightly in September with 10 wins against 16 losses.

The team’s most common batting order in 1998 was Randy Winn, CF, Wade Boggs, 3B, Quinton McCracken, LF, Fred McGriff, 1B, Bubba Trammell, RF, Paul Sorrento, DH, Miguel Cairo, 2B, John Flaherty, C, Kevin Stocker, SS. McGriff had the best offensive season on the team, slashing .284/.371/.443 and leading the team in home runs (19) and RBIs (81). respectively. He earned 2.9 bWAR. Miguel Cairo earned 3.2 bWAR due to his fielding contributions and his .268/.307/.367 slash line, 19 stolen bases, 49 runs scored and 46 RBIs. Quinton McCracken became a fan favorite by leading the team in runs scored with 77 and leading the regulars in batting average with .292. He slashed .292/.355/.410 with 7 home runs and 59 RBIs.

The team’s most common batting order in 1998 was Randy Winn, CF, Wade Boggs, 3B, Quinton McCracken, LF, Fred McGriff, 1B, Bubba Trammell, RF, Paul Sorrento, DH, Miguel Cairo, 2B, John Flaherty, C, Kevin Stocker, SS. McGriff had the best offensive season on the team, slashing .284/.371/.443 and leading the team in home runs (19) and RBIs (81). respectively. He earned 2.9 bWAR. Miguel Cairo earned 3.2 bWAR due to his fielding contributions and his .268/.307/.367 slash line, 19 stolen bases, 49 runs scored and 46 RBIs. Quinton McCracken became a fan favorite by leading the team in runs scored with 77 and leading the regulars in batting average with .292. He slashed .292/.355/.410 with 7 home runs and 59 RBIs.

Closer Roberto Hernandez had a good year, saving 26 games, or half the team’s wins. He earned 0.8 bWAR. The two top starters in wins above replacement value were Rolando Arrojo with 4.1 and the team’s first draft pick, Tony Saunders, with 3.1. Saunders was only 24 and might have become an even better pitcher as he gained experience. But he ruptured a tendon in his arm during a game in 1999, and never pitched again.

The Devil Rays did achieve Naimoli’s goal of not losing 100 games. All of their free-agent signings and draft picks combined to produce a record of 63 wins and 99 losses. They finished last in the American League East, 51 games behind the first-place Yankees, and 16 games behind the fourth-place Orioles. As one would expect for a first-year expansion team, the Devil Rays had the worst won-lost record in the league.

In 1999 the Devil Rays’ record would improve to 69-93, close to the worst record in the league. The 1999 draft yielded one of the best players in the team’s history, Carl Crawford, in round two. Their first-round pick, Josh Hamilton, also went on to star in major-league baseball — for other teams.

By this time the road to landing a franchise had already cost millions of dollars and was about to cost even more. During the offseason Naimoli ended the honeymoon for the team in Tampa Bay when he told the St. Petersburg City Council that if they didn’t pay for multimillion-dollar renovations to Tropicana Field, the club might move. Naimoli continued to micromanage the team, while feuding with advertisers, city and county officials, players, and, worst of all, fans. After the team set its all-time attendance record of 2,506,293 in 1998, attendance at Tropicana Field dropped every year until 2006, when Naimoli sold the Devil Rays to a group headed by hedge-fund manager Stuart Sternberg. That group celebrated the Devil Rays’ 10th-anniversary season in 2008 by improving 31 games over their 2007 season, going from worst to first in the A.L. East, winning the American League pennant, and making the team’s only World Series appearance to date. The Rays lost to the Philadelphia Phillies.

Chuck LaMar remained general manager from 1998 through 2007. The Devil Rays never achieved a winning record, and won as many as 70 games only once, in 2004, with Lou Piniella at the helm. LaMar summed up his time as general manager under Naimoli this way: “The only thing that kept this organization from being recognized as one of the finest in baseball is wins and losses at the major-league level.”15

PETER M. GORDON has over 35 years’ experience creating and curating content for platforms ranging from live theater to digital video. He is a long-time member of SABR whose articles and player bios have appeared in more than 14 SABR publications and on SABR.org. Peter is also an award-winning poet whose most recent collection is Let’s Play Two: Poems about Baseball. He lives in Orlando, Florida, and teaches in Full Sail University›s Film Production MFA program.

Tampa Bay Devil Rays

1998 Expansion Draft

ROUND 1

| PICK | PLAYER | POSITION | FORMER TEAM |

| 1 | Tony Saunders | p | Florida Marlins |

| 2 | Quinton McCracken | of | Colorado Rockies |

| 3 | Bobby Abreu | of | Houston Astros |

| 4 | Miguel Cairo | 2b | Chicago Cubs |

| 5 | Rich Butler | of | Toronto Blue Jays |

| 6 | Bobby Smith | 3b | Atlanta Braves |

| 7 | Jason Johnson | p | Pittsburgh Pirates |

| 8 | Dmitri Young | 1b | Cincinnati Reds |

| 9 | Esteban Yan | p | Baltimore Orioles |

| 10 | Mike DiFelice | c | St. Louis Cardinals |

| 11 | Bubba Trammell | of | Detroit Tigers |

| 12 | Andy Sheets | ss | Seattle Mariners |

| 13 | Dennis Springer | p | Anaheim Angels |

| 14 | Dan Carlson | p | San Francisco Giants |

ROUND 2

| PICK | PLAYER | POSITION | FORMER TEAM |

| 15 | Brian Boehringer | p | New York Yankees |

| 16 | Mike Duvall | p | Florida Marlins |

| 17 | John LeRoy | ss | Atlanta Braves |

| 18 | Jim Mecir | c | Boston Red Sox |

| 19 | Bryan Rekar | p | Colorado Rockies |

| 20 | Rick Gorecki | p | Los Angeles Dodgers |

| 21 | Ramon Tatis | p | Chicago Cubs |

| 22 | Kerry Robinson | of | St. Louis Cardinals |

| 23 | Steve Cox | 1b | Oakland A’s |

| 24 | Albie Lopez | p | Cleveland Indians |

| 25 | Jose Paniagua | p | Montreal Expos |

| 26 | Carlos Mendoza | of | New York Mets |

| 27 | Ryan Karp | p | Philadelphia Phillies |

| 28 | Santos Hernandez | p | San Francisco Giants |

ROUND 3

| PICK | PLAYER | POSITION | FORMER TEAM |

| 29 | Randy Winn | c | Florida Marlins |

| 30 | Terrell Wade | of | Atlanta Braves |

| 31 | Aaron Ledesma | of | Baltimore Orioles |

| 32 | Brooks Kieschnick | p | Chicago Cubs |

| 33 | Luke Wilcox | p | New York Yankees |

| 34 | Herbert Perry | 3b | Cleveland Indians |

| 35 | Vaughn Eshelman | of | Oakland A’s |

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and SABR.org, as well as Jonah Keri, The Extra 2%: How Wall Street Strategies Took a Major League Baseball Team from Worst to First (New York: Ballantine Books, 2011).

Thanks to the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library and the Orange County (Florida) Library.

Photos: Tampa Bay Rays, Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 Associated Press, Oneonta Star, March 10, 1995, from National Baseball Hall of Fame files.

2 Editorial page, St. Petersburg Times, March 10, 1995, from National Baseball Hall of Fame files.

3 Will Michaels, The Making of St. Petersburg (Charleston, South Carolina: History Press, 2012), 101-103.

4 Michaels, 104. The Making of St. Petersburg provides a detailed history of the city’s love of baseball.

5 Kevin M. McCarthy, Baseball in Florida (Sarasota: Pineapple Press, 1996), 175-176.

6 McCarthy, 176-177.

7 Marc Topkin, “Twenty Things We’ve Hated Over the Years.” Tampa Bay Times, March 25, 2018. Topkin, a longtime Rays beat reporter, produced a series of articles commemorating the team’s 20th anniversary.

8 Mel Antonen, “Devil Rays Lean to Pitching Youth,” USA Today, November 19, 1997.

9 Rob Neyer, Rob Neyer’s Big Book of Baseball Blunders (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), 258-260.

10 Bill Koenig, “Deals Help Devil Rays Grow Up,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, November 20, 1997: 22.

11 Pete Williams, “Rays Fans Juiced Over the Trop,” USA Baseball Weekly, April 14, 1998: 14.

12 Adam Sanford, “20 Years of Rays Baseball: 1998,” draysbay.com. draysbay.com/2017/10/16/16431104/tampa-bay-rays-20-years-remembering-inaugural-season (accessed July 4, 2018).

13 Interview with Roberto Hernandez on Rays telecast, March 31, 2018.

14 Interview with Mike DeFelice on Rays telecast, March 31, 2018.

15 Neyer, 260.