In MLBPA’s infancy, Jim Lonborg was in there pitching

This article was written by Saul Wisnia

This article was published in 1967 Boston Red Sox essays

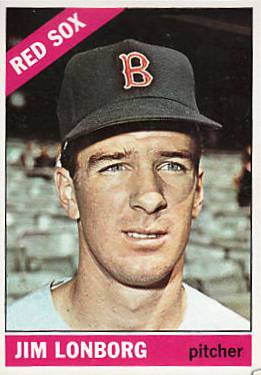

In addition to playing a key role in the rebirth of the Boston Red Sox, ace pitcher Jim Lonborg was also instrumental in helping all major-leaguers make off-the-field gains as the team’s official player representative.

In addition to playing a key role in the rebirth of the Boston Red Sox during the 1966 and ’67 seasons, ace pitcher Jim Lonborg was also instrumental in helping all major-leaguers make off-the-field gains as the team’s official player representative.

In addition to playing a key role in the rebirth of the Boston Red Sox during the 1966 and ’67 seasons, ace pitcher Jim Lonborg was also instrumental in helping all major-leaguers make off-the-field gains as the team’s official player representative.

It was the early days of the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLPBA), and each of the 20 teams had a rep. Jim Bunning of the Phillies, a Hall of Fame hurler and future United States Senator, was then heading up the player’s union, which appointed a labor attorney/economist named Marvin Miller as its executive director in ‘66.

“We would meet at a hotel in New York during the All-Star Game and World Series,” Lonborg remembers. “The major topics were the language in contracts and the minimum player’s salary — which was $6,000 when I started in ’65. We wanted better benefits for the ballplayers; the healthcare was already pretty good. There was discussion about the dispersion of World Series and All-Star money, and how much was given to the players for their pension fund.”

Lonborg recalls that the meetings grew longer and more frequent over the next few years. The MLBPA got the minimum player salary raised from $6,000 to $10,000 by 1968 (the first such raise in two decades), and sought to challenge the reserve clause, which for nearly a century had given team owners complete control over where and when players were traded, signed, or released irregardless of their seniority.

After veteran St. Louis Cardinals outfielder Curt Flood refused to accept a trade to Philadelphia in 1969, and then privately sued the MLB with the union’s support, Miller fought the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Although Flood lost, the action paved the way for free agency to emerge in 1975. “Curt was a very strong individual, and we were lucky to have someone with his conviction to see that through,” says Lonborg, who during this period also gained a close friendship with Miller and invited him to his wedding.

Jim stayed a rep through his 1972 season with the Milwaukee Brewers, a year marred by a 14-day player’s strike in April. The work stoppage earned players the right to salary arbitration and an additional $500,000 in their pension fund, however, and Lonborg looks back with pride on his entire MLBPA experience.

“It was great to be able to have a front-row seat in the development of the Player’s Association,” he says. “We had a bunch of young athletes determined to better their cause. By coming together as a group, we gained the power and strength necessary to succeed.”

SAUL WISNIA was born a Tony C. homer from Fenway Park 10 days before the Impossible Dream began there, and now works 100 yards from Yawkey Way as senior publications editor for Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. A former sports correspondent for the Washington Post and feature writer for the Boston Herald, he has written or coauthored numerous books on baseball and other subjects. A SABR-ite since 1992 and a founding member of the Boston Braves Historical Association, Wisnia lives in Newton with his children, Jason and Rachel, and more memorabilia than his wife, Michelle, knows about.