Introduction: Can He Play? A Look at Baseball Scouts and Their Profession

This article was written by Jim Sandoval

This article was published in Can He Play? A Look at Baseball Scouts and Their Profession (2011)

Countless hours traveling miles and miles on lonely back roads. They spend way too much time in hotels. Their front office expects them to constantly provide player reports and updates. They must dig through tons of coal to find a single diamond. So much of their time is spent away from family and friends, missing birthdays, anniversaries, and holidays. Their best friend is Rand McNally. Always asking the question, CAN HE PLAY? Such is the life of a professional scout.

The scouting profession evolved as the game of professional baseball grew and flourished. Pre-1900 major-league teams used a network of local people to recommend talent which the manager often scouted and signed personally. Minor-league teams frequently signed players from their local areas. On occasion the minor-league club would sell the contract of one of its players to a major-league team. Major-league clubs did not have minor-league affiliates as is generally the case today. The minor-league clubs were independent. Many relationships between major- and minor-league clubs were built on personal relationships rather than strictly business ones.

Teams in the early 1900s began to hire scouts who would follow up on tips on players provided by their manager’s network of bird dogs, a name given to those who followed players but did not work for a team and had no authority to sign a player. The official scouts, often called “ivory hunters” by the press, were hired by the major- league teams, following the minor leagues most of the time, looking for players whose contracts they would then purchase. Minor-league teams, being independent, often had their own scouts and many a local star from semiprofessional, high school, town teams, and the occasional collegian were first signed by minor-league clubs.

Many major-league scouts and/or their teams began to create informal agreements with a minor-league team or two to “farm” out players to gain experience. This is how they “grew” players. Sometimes a major-league scout recommended a player to his preferred minor-league team with the understanding the big-league scout would have an informal option on the player, the first chance to purchase the player’s contract.

Major-league teams soon began to add scouts to the payroll. In the early 1900s, teams might have one or two full-time scouts. Often they had one scout to cover west of the Mississippi River and another to cover east of the river. In some cases more than one club even shared the same scout. Ted Sullivan, one of the earliest full- time scouts, acted as an early version of the Major League Scouting Bureau, scouting for multiple teams at the same time. Teams were still using the bird-dog system, then sending out their full-time scouts to follow up on intriguing prospects.

The scouting profession became even more important when Branch Rickey of the St. Louis Cardinals began to develop the farm system. Teams began to own outright, or develop formal affiliations or working agreements with, many minor-league clubs. The major- league club began to supply more players directly, thus needing to increase the size of its scouting staff.

During this period, minor-league teams continued to hire their own scouts, as they were still able to sell contracts to a major-league club, but more and more players were now being signed directly by major-league teams and then being farmed out until deemed ready. The minor leagues evolved as well, soon creating levels from Class D to AA that players would pass through as they hoped to make their way to the majors.

Most teams began to create farm systems by the early 1930s, attempting to control or own at least one club at each level. Rickey’s Cardinals came to control multiple clubs at each level. Rickey was a pioneer in player development and his philosophy was “out of quantity comes quality.” The more players his scouts signed and his farm system developed, the more flexibility he would have in improving his major-league club. He could trade prospects for major leaguers and also sell contracts of players he would not need at the major-league level, often for a nice profit.

As more teams followed in Rickey’s footsteps, there was increasing competition for the better prospects. The teams with the better scouts fared well, but so did teams with the fatter bank accounts. Particularly after the end of the Second World War, competitive bidding for services drove up the prices paid in bonuses or incentives to greener and greener prospects. In large part as a measure to keep costs down, Major League Baseball instituted the amateur player draft in 1965. There was no longer a free-for-all bidding war for the best domestic prospects.

The player draft changed scouting tremendously. Scouts could no longer sign players immediately, or directly, and keep them away from other clubs. Clubs drafted players sequentially from a pool. Scouts now had to turn in a list of draft-worthy players to their team’s front office and then hope no other club selected their guy before their own organization had the opportunity.

Much of the scouting was still organized geographically. Area scouts cover a certain territory which varies from club to club. In prospect-heavy areas scouts will have a smaller territory, i.e. Southern California. In most parts of the country area scouts are responsible for three to four states. Current areas that are the strongest for players include California, especially the southern part, Texas, Florida, and – increasingly – Georgia.

While scouting for the current draft, area scouts will also compile a list of players to keep an eye on for future drafts. These will be high-school juniors and four-year-college freshmen and sophomores. They also may utilize the reports from the Major League Scouting Bureau to compile their follow list. Good scouts will network with coaches and coordinators of events such as showcases.

Showcases are a growing phenomenon in the scouting world. Some involve travel teams, often hand-picked teams with the better players from a large area who play in large tournaments throughout the year. These events allow scouts to see many players in one place in a short amount of time. Other showcases, often coordinated by scouts themselves, gather the top-rated prospects from a much larger area or in some cases nationwide. Among the more prominent of these are the East Coast showcase and the Area Code games.

Most organizations now have regional cross-checkers who follow up on the area scouts’ list. With larger and larger signing bonuses involved, front offices have virtually added another level of scouting called cross-checking. Most organizations also have a National Cross Checker, who then follows up on the regional cross checker’s information. (See Gib Bodet’s article in this volume.) In the case of possible high-round draftees, the general manager himself might see the player in person as well.

With the increasing cost of signing these high draft picks, many general managers are becoming much more involved in the process. Some GMs will personally scout potential first- and maybe second- round picks. The director of scouting will do the same. Teams want to get as many looks at the top players as possible. A short time before the draft, clubs will bring their scouting departments together to develop their “board.” (See Ben Jedlovec’s article.) They will discuss, argue, and finally decide on the ranking order of hundreds of possible draft choices. When a player is drafted he is said to “come off the board.”

The area scout is the true backbone of the scouting department. After the first few rounds an area scout will often be the only one in the organization with a report on the player. The area scout also takes the lead in the signing process, making the initial contact with the player and generally handling most if not all of the negotiation. On occasion an area scout will sign a nondrafted free agent; someone he sees can fill a role in the organization. Scouts sometimes hold tryout camps and sign the occasional player from these as well.

An area of some growth in scouting currently is the international arena, which remains outside the player draft. With the likes of Joe Cambria and Howie Haak opening the door, and Epy Guerrero and Bill Clark running through it, international scouting has grown geometrically in recent years. All teams now scout internationally and most maintain an academy in the top talent area, the Dominican Republic. Latin America is scouted heavily, with Venezuela in particular supplying many players. Islands in the Caribbean have provided players and an increasing number are coming from Pacific Rim nations. Australia has produced major leaguers. Europe is increasingly being scouted. Canada has been an excellent source of players. Baseball has truly become worldwide.

A final area where scouting has grown is on the professional scouting side. Teams will scout other organizations for potential trades, players to acquire through the Rule 5 draft, and as minor- league free agents. As in amateur scouting, clubs have different systems in pro scouting. Some scout by organization. The scout will be assigned a certain number of organizations to follow, usually from the major-league club down to High A ball. Others assign scouts to specific leagues while some scout regionally.

How many times have you heard the media report a big trade with words similar to these: “blank for blank and two minor leaguers?” Those minor-league players may be the key to the deal and were scouted and recommended by the club’s pro scouts. Many clubs have scouts with titles such as Special Assignment scout or Special Assistant to the GM who will be sent out to scout specific players, often when a potential trade is in the works.

Pro scouts of course ask the age-old question, CAN HE PLAY? Is he a major leaguer? If so, what role will he have: an everyday player, a utility guy, or just up for a cup of coffee? They will decide if starting pitchers project out as a 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 rotation guy, relievers as a closer, middle relief, or a long man. They will decide how they are developing, to ask regarding each player: Is he close to being major-league ready?

In the offseason clubs look for players to fill holes in their organization. Sometimes situations occur that need to be addressed by acquiring minor-league players. Perhaps a team’s AA club is going to be short on pitching and the AAA team needs a couple of outfielders. Minor-league free agents, scouted by their pro scouts, may be signed in the offseason to fill those gaps or a trade may be made.

Another area of pro scouting is called advance scouting. The advance scout travels ahead of his club, scouting upcoming opponents. He will write reports on tendencies, who is hot or cold, possible injuries, anything that might give his club an edge. Increasingly some teams are turning to technology to supplement or even replace advance scouts. They feel they can acquire enough information from scouting video, rather than needing to send a scout in person. Other clubs disagree with this philosophy, believing you can’t see it all from video and nothing can replace an experienced scout’s judgment on the spot. This is one debate that may never be settled.

Assessing video is a skill in itself, and a legitimate form of scouting. Finding the diamond in the rough, the 15- or 16-year- old kid who may develop the body and attributes of a true athlete remains one of the more exciting challenges for some scouts, but pro scouting is in the here-and-now, dealing with opponents on the field today. Both are essential parts of the successful big-league team today, as is – indeed – the full range of talent assessment and evaluation, that is, of scouting. Whatever the tools that might help, the primary question regarding any prospect remains: Can he play?

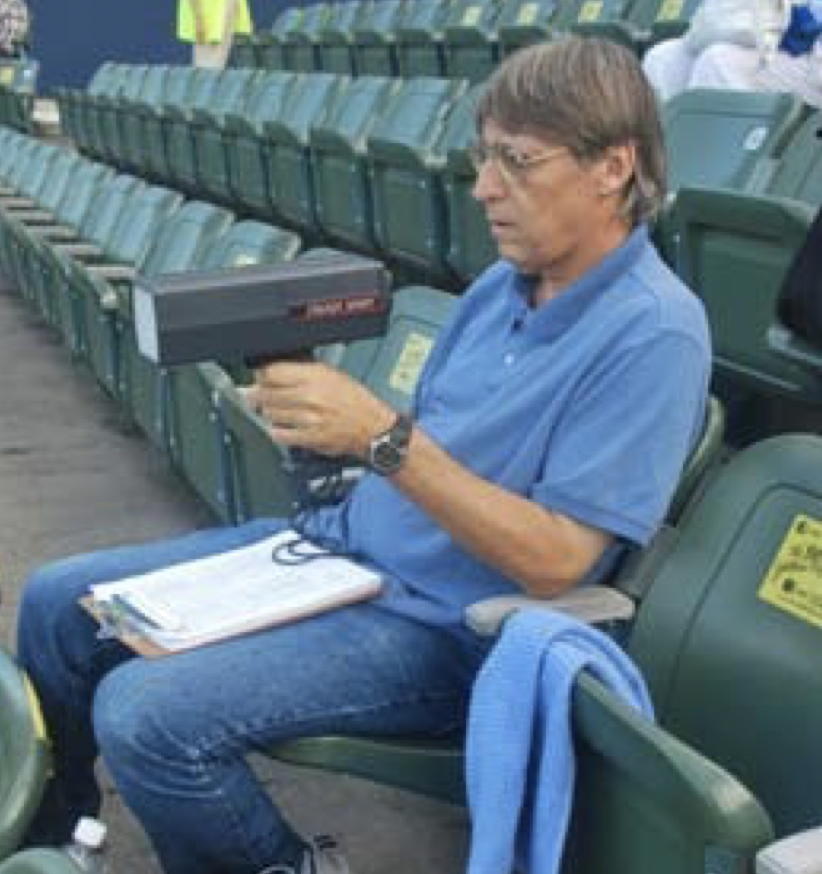

JIM SANDOVAL (1958-2012) was a history teacher and freelance baseball writer who collected ballparks and baseball scout sightings. He contributed to SABR’s NL and AL Deadball Stars books and The Fenway Project. A former small college baseball player, he realized he was more of a prospect writing baseball than playing it. He was the longtime co-chair of SABR’s Scouts Committee.

Jim Sandoval at Joe Davis Stadium, Huntsville, Alabama, August 2011.