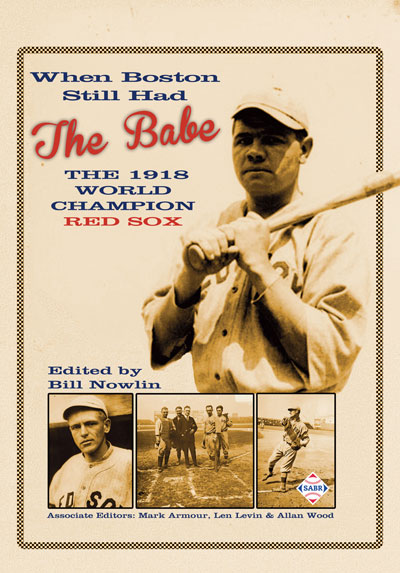

Introduction: When Boston Still Had the Babe: The 1918 World Champion Red Sox

This article was written by Allan Wood

This article was published in 1918 Boston Red Sox essays

Late into the infamous 86-year championship drought of the Boston Red Sox – from 1918 to 2004 – it became nearly taboo to talk seriously about the 1918 team.

Late into the infamous 86-year championship drought of the Boston Red Sox – from 1918 to 2004 – it became nearly taboo to talk seriously about the 1918 team.

One reason for that reluctance was the sullied reputation of the team’s then-owner, Harry Frazee – the man who sold Boston’s beloved superstar, Babe Ruth, to the New York Yankees. Then there were the four World Series losses – 1946, 1967, 1975, and 1986 – each loss coming in the seventh and final game, reinforcing the image of the Red Sox as a team unable to win when it truly counted.

Over the last decade, the national sports media became obsessed with the idea that this chronic futility was caused by a beyond-the-grave curse. Indeed, media often reported with a straight face that the Boston franchise was cursed. The very year “1918” became a taunt at Yankee Stadium.

Taken together, one can well understand why many Red Sox fans wanted to forget the year 1918 altogether.

But winning a World Series championship is nothing to be ashamed of, and nothing to be brushed under history’s rug. 1918 was a fascinating season – not only for the Red Sox, but for major league baseball in general.

The United States had entered Europe’s Great War in April 1917, but few players enlisted that summer and the war had very little direct impact on the national sport. During the winter of 1917-18, however, dozens of major league players left their teams. They either enlisted in the military or accepted jobs in war-related industries, such as shipyards or munitions factories.

Some of the players the Red Sox lost were: manager/second baseman Jack Barry, left fielder Duffy Lewis (who led the team in batting and slugging in 1917), pitcher Ernie Shore, and utility infielders Hal Janvrin, Mike McNally, Del Gainer, and Chick Shorten.

As 1918’s spring training loomed, most owners bided their time, deciding to wait until the beginning of the season was closer and their needs became more certain. The one owner who was the most pro-active, who took the biggest and quickest steps to rebuild his team’s roster, was Red Sox president Harry Frazee. In December 1917 and January 1918, Frazee made two headline-grabbing deals with Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics, sending a handful of players and the sizeable sum of $60,000 to Mack for pitcher Joe Bush, catcher Wally Schang, infielder Stuffy McInnis, and outfielder Amos Strunk.

In the wake of this wheeling-and-dealing, a January editorial in the New York Times expressed disgust at the “disorganizing effect” that Frazee and Chicago Cubs president Charlie Weeghman were having on the national game by “offering all sorts of money for star ballplayers”. (Weeghman had spent a small fortune to acquire the superb battery of pitcher Grover Alexander and catcher Bill Killefer from the Philadelphia Phillies.) The Times wrote: “The club owners are not content to wait for a few seasons while their managers develop a pennant winner, but have undertaken to accomplish in one year what other clubs have waited years to achieve.”

In other words, the Times was accusing Harry Frazee of trying to buy the American League pennant.

This view of Frazee as a free-spending, win-at-all-costs magnate clashes with his modern-day image. If baseball fans know Frazee’s name at all, it’s because he was the man responsible for selling Babe Ruth to the Yankees after the 1919 season. But in 1918, Frazee was intent on bringing another World Series title to Boston. The Red Sox won the championship in 1912, their first year at Fenway Park, then won back-to-back titles in 1915 and 1916. (The cross-town Boston Braves had swept the 1914 series.) After a second-place showing in 1917 – Boston won 90 games, but finished 10 games behind the eventual World Series champion Chicago White Sox – Frazee was determined to put the Red Sox back on top.

Boston was also fortunate in that most of its war-related personnel losses came well before spring training. Many other clubs started 1918 strong, but saw their lineups decimated as the summer went on.

In addition to the two deals with the Athletics, Frazee hired former International League president Ed Barrow to manage the team. Barrow had previously managed the Detroit Tigers in 1903 and part of 1904 (for a combined record of 97-117). Next, Frazee signed George Whiteman, a 35-year-old outfielder, to replace Lewis. Whiteman was a career minor-leaguer, though he did have cups of coffee with both the Red Sox (1907) and Yankees (1913). And a few weeks before Opening Day, Frazee traded for Cincinnati’s 34-year-old second baseman Dave Shean. Whiteman and Shean were both out of the draft’s age range (21-31).

Of the eight regulars in Boston’s Opening Day lineup, only two were holdovers from the previous year: right fielder Harry Hooper and shortstop Everett Scott.

The great Red Sox teams of the 1910s were built around excellent pitching and air-tight fielding. The team’s offense had been below league average in 1916 and 1917 (and would be again in 1918), so it was fortunate that the 1918 pitching staff remained largely intact. Anchoring the rotation were Babe Ruth and Carl Mays, a left-right tandem that had combined for 41 wins in 1916 and 46 wins in 1917. Dutch Leonard was another lefty and newcomer Joe Bush would take Shore’s spot as the fourth starter. After Leonard took a shipyard job in mid-season, right-hander Sam Jones took over. Those five pitchers – Mays, Ruth, Bush, Leonard, and Jones – would start all but six of Boston’s 126 games.

The roster upheaval caused by the war also gave plenty of marginal players the opportunity, however brief, to play in the major leagues. In Boston, a handful of players counted their time with the 1918 Red Sox as their only big league experience: Eusebio Gonzalez (seven plate appearances over three games) Red Bluhm (one at-bat as a pinch-hitter), George Cochran (.117 average), and Jack Stansbury (who slugged .149 in 20 games).

In 1918, a summer-long soap opera played out over whether the remaining players would receive a blanket exemption from the draft, as other entertainers such as stage actors enjoyed. At first, the National Commission – the sport’s ruling body, comprised of American League president Ban Johnson, National League president John Tener, and Cincinnati Reds owner August Herrmann – simply assumed that an exemption would be granted. When baseball was deemed “not essential”, the Commission scrambled to file requests for extensions, desperately hoping to finish the regular season.

The Commission bumbled its way through the summer, insisting to sportswriters that it would be happy to cancel the season because winning the war was the highest priority, then begging the War Department for a further extension, so owners wouldn’t lose as much money. The government finally set September 1, 1918 as the absolute deadline. The owners decided against continuing the season past that point with players either under or over draft age.

Not only did the regular season come to an early close, the World Series almost did, too. The 1918 World Series, played in early September, was nearly derailed by a furious off-field battle between the Red Sox and Chicago Cubs players, on one side, and the National Commission on the other, over what percentage of the gate receipts would be awarded to the winners and losers of the series.

In the three previous years, 1915-17, the shares were almost $4,000 for each player on the winning team and $2,500 for each player on the losing side. In some cases, those amounts were as much as a player’s annual salary.

Ticket prices for the 1918 World Series were reduced with the hope of boosting attendance. In 1917, box seats were $5.00, grandstand seats were $3.00, pavilions were $2.00, and bleachers were $1.00. For the 1918 series, box seats were reduced to $3.00 and the other ticket prices were cut in half.

The plan did not work. The crowds for the first three games at Comiskey Park were 19,274, 20,040 and 27,054 (the third game was on a Saturday afternoon thanks only to the rainout of Game One). The first two games of the 1917 World Series, also played at Comiskey, drew over 32,000 each.

The National Commission had also decided, for the first time, that players on the second-, third- and fourth-place teams in each league would get a cut of the World Series dough. The Commission also “volunteered” to donate some of the players’ shares to charity – without consulting the players. The players learned about all of this as the Series began. It looked like the shares could be cut by as much as 75%.

The Commission refused to meet with the players. The two teams, led by Red Sox captain Harry Hooper, decided to not take the field at Fenway Park for Game Five until the matter was resolved.

When Ban Johnson arrived at the park drunk, and with no intentions – or ability – to seriously discuss finances, and with nearly 25,000 fans waiting for the start of the game, the players reluctantly agreed to play that afternoon, and to finish the Series. A teary-eyed Johnson assured Hooper the players would not be punished for their one-hour delay of Game Five. One month later, Johnson broke his promise, as the Commission refused to award championship emblems, the equivalent of World Series rings, to the Red Sox. (The individual shares ended up being $1,100 for the Red Sox and $670 for the Cubs.)

1918 was also the summer that a young man from Baltimore, Maryland, began his unprecedented transition from ace pitcher to the greatest hitter in baseball history.

Babe Ruth had been one of baseball’s best pitchers in 1916 and 1917, but three weeks into the 1918 season, faced with a depleted roster, no reinforcements, and a need for more offense, Ed Barrow moved Ruth into the regular lineup, eventually playing him at first base and in left field.

Although Ruth’s potential as an everyday player had been an occasional topic in the sports pages since his rookie season of 1915, when he was actually out there, there was plenty of debate. Would Ruth’s weaknesses at the plate be quickly discovered and exploited by opposing pitchers? Would he ruin his arm making long throws from the outfield? Could he play every day and continuing pitching?

On May 6, 1918, in a game against the Yankees at the Polo Grounds, Ruth debuted at first base and batted sixth. He went 2-for-4, including a two-run home run. The next day, in Washington, Ruth was moved up to the #4 spot in the lineup – and celebrated the promotion with another home run, off Senators ace Walter Johnson. In the final game of the Senators series, on May 9, Ruth lost a 10-inning complete game on the mound, but also went 5-for-5 with three doubles, a triple, and a single. (That is still the major league record for extra-base hits by a pitcher in an extra-inning game.)

Oddly enough, Boston lost their first six games with Ruth in the field and slipped out of first place. Melville Webb Jr. of the Boston Globe was not impressed: “Putting a pitcher in as an everyday man, no matter how he likes it or how he may hit, is not the sign of strength for a club that aspires to be a real contender.”

As Ruth’s hitting began drawing more attention, his desire to pitch dwindled. This didn’t sit well with Barrow, especially after Dutch Leonard’s departure left the team without a left-handed starter. Ruth insisted his left wrist was sore; he and Barrow argued throughout June. After a dugout confrontation in Washington on July 2, Ruth quit the team, fleeing to his father’s house in Baltimore.

Babe considered joining a shipyard and playing for the company team, but quickly learned that the shipyard would also want him to pitch. He’d also be taking a huge cut in pay. Ruth returned to the Red Sox a couple of days later, patching up his differences with Barrow. As the Red Sox got hot in the month of July, Ruth turned in what was arguably the greatest nine- or ten-week stretch of play the game has ever seen.

In one 10-game period (July 6-22) during a Fenway homestand, Ruth batted .469 (15-for-32) with four singles, six doubles, and five triples. Although he did not hit any home runs in July or August, Ruth was feared as a batter all year long. He was walked intentionally in the first inning as often as he was in the ninth inning. In mid-June, the St. Louis Browns gave him a free pass in five consecutive plate appearances over two games. As far as can be determined, that remains a major league record (Barry Bonds was also walked intentionally five straight times on September 22-23, 2004).

After returning from his Fourth of July defection, Babe took his turn on the mound every fourth day and proved that he was still one of the game’s top pitchers. Ruth made 11 starts and won nine of them (all complete games), including the pennant-clincher against Philadelphia. In his last 10 starts of the season, he allowed more than two runs only once.

Of the many nicknames Ruth earned during his Red Sox career — the Big Fellow, Tarzan, the Caveman, the Colossus — one was particularly apt. As the Colossus of Rhodes was believed to have straddled the entrance to the harbor of ancient Greece, his New England namesake towered over the national sport in 1918, one huge foot planted on either side of baseball’s pitching and hitting camps.

Imagine Johan Santana playing first base or DH-ing in every game he didn’t pitch. Then imagine Santana remaining a dominant pitcher while putting up a batting line to rival Barry Bonds or Albert Pujols. That was Babe Ruth in 1918.

Ruth wasn’t the first major leaguer to pull double duty, but almost all of the players who pitched and played the field in the early 1900s either had very short careers or their performances were unexceptional.

In contrast, Babe led both leagues in slugging average by a wide margin in 1918 – his .555 topped Ty Cobb’s second place finish of .515 in the AL and Edd Roush’s NL-best .455. His 11 home runs were more than the totals of five other AL teams. Ruth finished second in doubles, third in RBI, fifth in triples, and eighth in walks — all accomplished in 100 to 175 fewer plate appearances than his American League peers.

Ruth’s 2.22 ERA was eighth best in the AL. He allowed an average of only 9.52 hits and walks per nine innings, second only to the Senators’ Walter Johnson. Ruth had the third lowest opponents’ on-base average and fourth lowest opponents’ batting average.

In the World Series, Ruth beat the Cubs in Games One and Four, setting a new World Series record of 29.2 consecutive scoreless innings, a streak he began in 1916. Ruth set many records during his career, but that accomplishment was the one of which he was most proud. It would stand until the Yankees’ Whitey Ford broke it in 1961.

When lists are made of baseball’s top dynasties, the Red Sox teams of the 1910s are rarely mentioned. While they are not in the upper echelon of the 1906-12 Chicago Cubs (713-356, .667) or the 1936-42 New York Yankees (701-371, .654), their seven-year winning percentage from 1912-18 (632-406, .609) is better than the seven-year run of the 1996-2002 Yankees (685-445, .606).

In this book, 28 members of the Society for American Baseball Research have compiled the most in-depth look at the 1918 Red Sox. They have unearthed a wealth of information – much of it never seen before – about every one of the 32 players who suited up that year, from Harry Hooper and Everett Scott, who played in all 126 games, to Red Bluhm, who had one pinch-hitting opportunity.

For Red Sox fans, the life-changing events of October 2004 should forever remove any stigma attached to the 1918 club. And for all baseball fans, it will be a chance to travel back to a time when the Boston Red Sox were the kings of the diamond.

ALLAN WOOD is the author of Babe Ruth and the 1918 Red Sox. He also writes the blog “The Joy of Sox.” Allan has been writing professionally since age 16, first as a sportswriter for the Burlington (Vt.) Free Press, then as a freelance music critic in New York City for eight years. His writing has appeared in numerous publications, including Baseball America, Rolling Stone, and Newsday. He has contributed to two SABR books: Deadball Stars of the American League and Deadball Stars of the National League. He currently lives in Ontario, Canada.

Related links: