It’s Not Fiction: The Race to Host the 1954 Southern Association All-Star Game

This article was written by Ken Fenster

This article was published in Fall 2010 Baseball Research Journal

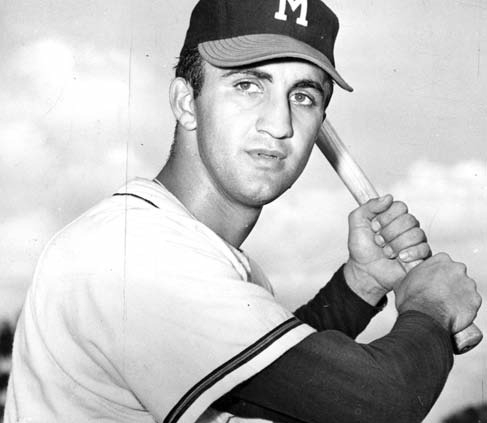

Frank Torre, Crackers first baseman whose mother, sister, and brother Joe traveled from New York to Atlanta to watch his team in a crucial game against the rival Birmingham Barons on July 8, 1954.

For the first eleven days of July 1954, the Atlanta Crackers, the Birmingham Barons, and the New Orleans Pelicans fiercely battled each other on the playing field for the honor of hosting the Southern Association All-Star game. Their intense struggle culminated in a spectacular, tense game that ended in grand storybook fashion in Atlanta on July 11. The race in general and this game in particular were something right out of an epic novel. There was drama, anxiety, excitement, a hero, a villain, a damsel in distress, and catharsis. The All-Star game itself, played on July 15, was decidedly anticlimactic.1

The story of the great race to host the 1954 Southern Association All-Star game began in December 1953. At their annual meeting, league directors changed the rules for determining the site of the game for the upcoming season. In previous years, the team in first place after the completion of games played on July 4 hosted the midseason event on July 15. For 1954, that privilege would go to the team in first place after games played on July 11. League directors made this change to avoid the possible embarrassment of the first-place team on July 5 sliding to third or even fourth place—it had happened in the past—by the time the All-Star game arrived.2

Operation Ticktock Begins

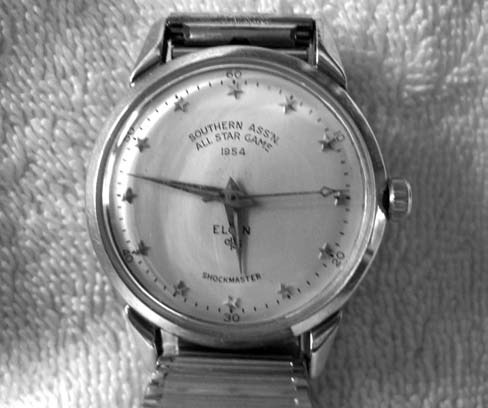

To be sitting atop the league standings on that midseason date predetermined by league officials was tantamount to winning the first-half pennant of a split season. It gave the team and its city bragging rights.3 Moreover, the owner and the players had financial motives for wanting to host the All-Star game. For the owner, hosting the All-Star game meant an extra payday at the gate, and it could be lucrative. Attendance at fifteen previous All-Star games had averaged slightly more than 10,100. Four All-Star games in Atlanta had averaged more than 13,450.4 For Earl Mann, the Crackers’ owner, whose only source of income was his baseball franchise, an extra gate of this magnitude would be a financial bonanza. The players on the team hosting the game received from the league a wristwatch valued at $75, a considerable sum—the average monthly salary in the Southern Association was about $600.5 The Atlanta players nicknamed the race for the 1954 All-Star game Operation Ticktock.6

Operation Ticktock began in earnest on July 2, with the Atlanta Crackers, the Birmingham Barons, and the New Orleans Pelicans all in the chase. Atlanta clung to a slight lead. The top four teams in the standings on that date:

|

Won |

Lost |

Winning Pct. |

Games Behind |

|

|

Atlanta |

47 |

31 |

.603 |

|

|

Birmingham |

48 |

34 |

.585 |

1 |

|

New Orleans |

45 |

36 |

.555 |

3.5 |

|

Chattanooga |

42 |

40 |

.512 |

7 |

Between July 2 and July 11, Atlanta and New Orleans played twelve games, and Birmingham eleven.7 Their schedules were nearly identical. Atlanta had four games with New Orleans, four with Mobile, and four with Birmingham. Birmingham played four against New Orleans, three against Mobile, and four against Atlanta. New Orleans had four with Atlanta, four against Mobile, and four with Birmingham. The schedule put each team’s destiny in its own hands. The Crackers, the Barons, or the Pelicans were all in the same position: The team that took care of business in their games with the other two contenders—regardless of what other teams did on the field—would win the race.

However similar the schedule for the crucial next ten days may have been for the three top teams, it slightly favored New Orleans at the expense of Atlanta and Birmingham. New Orleans and Atlanta had one more game against the weak, sixth-place Mobile Bears than did Birmingham. New Orleans played eight of its next twelve games at home; of its next twelve, Atlanta played only four at home; and the unfortunate Barons played all their next eleven games on the road. Birmingham had only one doubleheader between July 2 and July 11. New Orleans and Atlanta had excruciating back-to-back doubleheaders on July 4 and July 5, a situation that could wreak havoc with their pitching staffs. At least the Pelicans played their doubleheaders on their home field. Atlanta had the extra burden of playing its doubleheaders on the road and in two different cities, New Orleans on July 4 and Mobile on July 5.

The three teams each played .500 ball in their first series in July. Atlanta and New Orleans split their four-game set, and the Barons split a brace of games with the Mobile Bears. The Crackers and the Pelicans caught a huge break when rain cancelled Birmingham’s game with Mobile on July 4. After games played on July 4, Atlanta still led the league by a slim one-game margin over Birmingham. The standings were:

|

Won |

Lost |

Winning Pct. |

Games Behind |

|

|

Atlanta |

49 |

33 |

.598 |

|

|

Birmingham |

49 |

35 |

.583 |

1 |

|

New Orleans |

47 |

38 |

.553 |

3.5 |

|

Chattanooga |

46 |

40 |

.535 |

5 |

On July 5, Atlanta split a doubleheader with Mobile, losing the second game in the eleventh inning on rightfielder Chuck Tanner’s costly error. Meanwhile, in New Orleans, the Pelicans and Barons were rained out, forcing them to play back-to-back doubleheaders on the July 6 and 7. Atlanta wasted a second golden opportunity to pull further ahead of its pursuers when the team lost another game it should have won, 1–0, to the lowly Bears. In the end the Crackers salvaged a split in the series, winning the final game 3–1 behind the stellar hurling of Leo Cristante, the league’s leading pitcher. In New Orleans, the Pelicans beat the Barons three out of four games to move within 2.5 games of league-leading Atlanta. After games played on July 7, with each contending team having four games left to play through July 11, the standings were:

|

Won |

Lost |

Winning Pct. |

Games Behind |

|

|

Atlanta |

51 |

35 |

.593 |

|

|

Birmingham |

50 |

38 |

.568 |

2 |

|

New Orleans |

50 |

39 |

.562 |

2.5 |

|

Chattanooga |

48 |

41 |

.539 |

4.5 |

Although Atlanta had played mediocre ball since July 2, the team had gained a full game over Birmingham. But New Orleans had moved one game closer to first. Any of these three teams could still win the honor, and the upcoming four-game series between the Crackers and the Barons in Atlanta’s Ponce de Leon Park between July 8 and July 11 now loomed crucial. This “All-Star Series” or “All-Star Showdown,” or “July’s own Little Dixie Series,” as the Atlanta sportswriters called it, excited fans in Birmingham and Atlanta and generated hometown boosterism in both cities. The Atlanta sportswriters predicted large crowds for the series, especially for the opener on July 8, which could potentially determine the winner of the race.8

Showdown Series: Birmingham at Atlanta

Of the three teams vying for the All-Star game, Atlanta certainly had the best chance. To bring the game to Atlanta, the Crackers had to win only one of their four games with the Barons while the Pelicans had to lose one of their four games with the Bears. That outcome would give Atlanta first place by .002 points over Birmingham and .008 points over New Orleans. Two Atlanta wins over Birmingham would give the Crackers the All-Star game even if the Pelicans swept four games from Mobile. For Birmingham to win the honor, the Barons would have to sweep their four-game series on the road in Atlanta. For New Orleans to get the game, the Pelicans would have to sweep the Bears while the Barons took three of four from the Crackers.

Conditions were perfect for baseball when the Crackers and the Barons squared off on July 8 in Ponce de Leon Park for the opening contest of their decisive four-game series. The temperature at game time was a comfortable 77 degrees under clear skies. An excited crowd of 6,537, one of the largest of the season to date, came to cheer on the Crackers to, as they hoped, a victory that, combined with a Pelican loss in Mobile, would give Atlanta the All-Star game. The throng included the mother, sister, and fat teenage brother, Joe, of Cracker first baseman Frank Torre—they had traveled from New York to watch the slick-fielding infielder and his teammates take on the Barons.9 The Crackers did not disappoint. They convincingly defeated the Barons 6–3 behind Bill George’s stellar pitching, third baseman Paul Rambone’s sensational defense, which stifled three Baron rallies, and an offense that banged out eleven hits, including eighth-inning home runs by catcher Jack Parks and shortstop Billy Porter that iced the game. Atlanta’s victory dropped Birmingham to third place, eliminated the Barons from contention for the All-Star game, and brought the Crackers one step closer to getting it. All they needed now was a New Orleans loss to Mobile. But the Pelicans beat the Bears 4–1, keeping their slim hopes alive. The race for the midseason extravaganza would continue for at least one more day.

WSB-TV televised the game, and a slight rain had fallen during the day, but still an enthusiastic crowd of 6,770 fans turned out for ladies night on July 9. They watched Birmingham deny Atlanta the victory they needed to clinch. While Cracker batters squandered four opportunities to score, the Barons broke up a deadlocked pitchers’ duel with solo runs in the eighth and ninth innings to defeat Atlanta 2–0. In Mobile the Pelicans won again, downing the Bears 5–1 and keeping their hopes alive. The location of the game was still undecided, with Atlanta and New Orleans each having two games left to play.

On Saturday, July 10, a crowd of 8,293, the second-largest of the season to date, watched the Crackers lose yet another game to the Barons, 6–4. Atlanta scored all its runs on pitcher Dick Donovan’s two-run homer in the fifth inning and second baseman Frank DiPrima’s two-run shot in the ninth. Otherwise, Cracker pitching faltered and the offense sputtered, collecting a measly five hits and striking out ten times, and the infield defense simply collapsed, committing errors and bad judgment. New Orleans pounded Mobile again, 12–7.

Going into games scheduled for the crucial day, July 11, the standings of the top four teams:

|

Won |

Lost |

Winning Pct. |

Games Behind |

|

|

Atlanta |

52 |

37 |

.584 |

|

|

New Orleans |

53 |

39 |

.576 |

0.5 |

|

Birmingham |

52 |

39 |

.571 |

1 |

|

Chattanooga |

50 |

41 |

.549 |

3 |

The race would go down to the wire in a photo finish between Atlanta and New Orleans. Atlanta still had the better chance. A Pelican loss to the Bears or a Cracker victory over the Barons would ensure first place for Atlanta. Despite the Crackers’ poor performance in the last two games, circumstances strongly favored them against Birmingham on July 11. Their scheduled starting pitcher was Leo Cristante, who, at 16-4, easily led the league in wins. Moreover, Cristante had rightly earned the nickname “Baron Killer,” having beaten Birmingham eight straight times in the past two seasons.10 New Orleans could still cop the All-Star game, but the path to it was more demanding. The Pelicans had to win again and had to depend on the Barons to defeat the Crackers one more time. With Cristante on the mound for Atlanta, that seemed a Herculean task.

“Love and Luck to My Brothers”

Earl Mann, the Crackers’ owner, had staged for Ponce de Leon Park a one-hour concert, featuring some of the biggest names in country-western music, to take place before what was now shaping up as the most important game of the season.11 While Hank Snow, the Smith Brothers, Boots Woodall, and other performers created a carnival atmosphere for the fans—the official attendance was 8,385—Atlanta manager Whitlow Wyatt, the former pitching star for the Brooklyn Dodgers, created a sober, solemn atmosphere in the Cracker clubhouse. He read aloud to the players an inspirational and heartwarming letter he had received from a 15-year-old girl, Billye Hinson, an only child from Lawrenceville, Georgia.12 It was dated July 8. Greeting him as “Pop,” the youngster was thrilled that Wyatt, a total stranger and a very busy and famous man, had responded to her first letter. Although she had heard before the advice Whitlow had offered her, “never did it mean so much, or was it said so beautifully as it was in your letter. I guess that’s because this time it came from someone great, who has really had a chance to know.” Billye was especially elated with Whitlow’s permission to adopt him and the players as her brothers. She provided her new “wonderful brothers” with a religious poem, extolling the virtues of Christian labor. The young girl concluded with an appeal for patience and understanding: “I hope you don’t mind hearing all my problems and troubles, and I hope you don’t mind how often I write. All I can say is thanks for everything. Give my love and luck to my brothers. You have my prayers, blessings, luck and best wishes for all.” Whitlow and some of the players choked up during the reading, struggling to hold back tears.13

Just before the start of the game, Whitlow again surprised his players and everybody else. This time he irked Leo Cristante and shocked the sportswriters and fans on hand at the ballpark by giving the starting pitching assignment to left-hander Bill George. Whitlow believed that Birmingham had difficulty against left-handers, and George had already defeated the Barons once this series. When asked about Cristante’s uncanny string of victories against Birmingham, Wyatt tersely responded, “I never beat anybody with a jinx yet. You beat or get beat on the field, not with a jinx.”14 Whitlow’s strategy backfired—badly.

Operation Ticktock is what the Atlanta players nicknamed the race to play host to the Southern Association All-Star game in 1954.

Crunch Time

Working on only two days’ rest, George yielded four hits and four runs in one-third of an inning before Wyatt replaced him with another left-hander, Dick Kelly. The park organist, Johnnie Nutting, played “Say It Isn’t So.”15 But it was. The Crackers were in grave danger of losing again to the Barons and of losing the All-Star game to the Pelicans, who were leading the Bears 1–0 in the third inning.

The Crackers battled back, pushing across two runs in the second inning and two more in the third to tie the score 4–4. And with Cristante finally on the mound, victory seemed hopeful. The “Baron Killer” promptly gave up two runs, giving Birmingham back the lead, 6–4. In the fifth and again in the sixth innings, the Crackers put the tying runners on base, but the offense floundered, stranding them. The score remained 6–4 when news arrived that New Orleans was leading Mobile, 3–1, in the sixth inning.

Jim Solt

With Birmingham still holding its 6–4 lead, the Crackers had a man on first with two out in the bottom of the seventh inning. Atlanta then caught a huge break when three Baron defenders allowed a high fly ball hit by Cracker catcher Jack Parks to fall harmlessly to the ground in foul territory near the right-field line. Parks walked, and for the third inning in a row the Crackers had two runners on base. Whitlow then called on Jim Solt, the other half of the Cracker catching platoon, to pinch-hit for Cristante, a good-hitting pitcher. Once again the Atlanta manager’s strategy surprised the sportswriters in the press box and the fans in the stands.16 With the count two balls and one strike, Solt guessed that Baron pitcher Dave Benedict would throw a curve. Solt guessed right, and he launched the ball over the left-field fence, just beyond the outstretched glove of left-fielder Dick Tettelbach, for a three-run home run that put the Crackers ahead 7–6. The crowd erupted. The Cracker players mobbed their teammate as he crossed home plate. Solt’s electrifying home run thoroughly demoralized the Barons and made the Pelican victory over the Bears irrelevant.17

The hard-fought race to host the Southern Association All-Star game, a race that had begun ten days earlier, was now finally over. Solt’s improbable blast traveled 350 feet in Atlanta and “was clearly heard 373 miles away in Mobile.”18 Among the shouts heard in the Cracker clubhouse, where the players were celebrating and congratulating each other, especially Solt, with hard slaps on the back, was “operation tick tock completed.”19 The standings after the completion of games played on July 11:

|

Won |

Lost |

Winning Pct. |

Games Behind |

|

|

Atlanta |

53 |

37 |

.589 |

|

|

New Orleans |

54 |

39 |

.581 |

0.5 |

|

Birmingham |

52 |

40 |

.565 |

2 |

|

Chattanooga |

50 |

43 |

.538 |

4.5 |

On July 15, one day after Atlanta experienced record-setting 98-degree heat, hail, high winds, heavy rain, and the worst electrical storm in years, a crowd of 16,808 fans, the largest to date for a Southern Association All-Star game, turned out to watch the Crackers take on the league’s best at Ponce de Leon Park. They crammed every nook and cranny of the ballpark, which seated only 14,500.20 They “rocked the joint,” according to one report, “and most of ’em went away hoarse.”21 Fans began shouting and cheering in the second inning, when the Crackers took a 4-0 lead, and did not stop until the game ended. The Crackers trounced a powerful offensive All-Star lineup, 9–1. A trio of Atlanta hurlers yielded only four base hits, giving up a meaningless run in the eighth inning. Cracker left fielder Bob Montag hit two solo home runs. Catcher Jack Parks hit a three-run home run and had four RBIs. League sportswriters voted Parks the game’s most valuable player.

Ironically, Jim Solt, whose home run gave Atlanta the honor of hosting the All-Star game, was not in the lineup. In fact, he was not even in uniform, and he was not at the ballpark. He was at his home in Charleston, South Carolina, tending to his young wife, who was dying of a brain tumor.22 Mae Jeanette Solt died on November 5, 1954, about five weeks after the season ended.23

Jim Solt continued his baseball career for several more years, but never again would he or the Atlanta Crackers experience anything like the first eleven days of July 1954. The great race to host the Southern Association All-Star game ended when Solt, a parttime player and a most unlikely hero, hit the most dramatic home run of his then seven-year career. Furman Bisher, sports editor of the Atlanta Constitution, compared it to Bobby Thomson’s 1951 shot heard ‘round the world. “Solt,” he wrote, “is only a cotton-picking Thomson, for his shot was heard just around the Southern Association, not the world. But the situation had everything it takes for a heart attack.”24 Years and even decades later, Solt, Earl Mann, Whitlow Wyatt, and Furman Bisher vividly remembered the most famous and thrilling home run in more than fifty years of Atlanta Cracker baseball history.25

KEN FENSTER is professor of history at Georgia Perimeter College, Clarkston Campus. His baseball writing has appeared in “Nine”, “The New Georgia Encyclopedia”, “The African American National Biography”, and “The Baseball Research Journal”. He currently is researching the life of Atlanta Cracker executive Earl Mann.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Tony Yoseloff and the Yoseloff Foundation for the Yoseloff/SABR Baseball Research Grant that helped make this article possible.

Notes

1 This article is based primarily on the two Atlanta daily newspapers, the Atlanta Journal and the Atlanta Constitution, July 1–16, 1954.

2 Atlanta Journal, December 3, 1953; The Sporting News, December 9, 1953.

3 The Southern Association had used a split season in 1928, 1933, 1934, 1943, and 1944. From 1935 through 1942 and beginning again in 1945, the Southern used the Shaughnessy Playoff system. See Charles Hurth, Baseball Records: The Southern Association, 1901–1957 (New Orleans: Southern Association, 1957), 7–8.

4 All-Star Game attendance data from Hurth, 130.

5 For reference to the watch and its value, see Atlanta Constitution, July 13, 1954; for Southern Association salaries in 1954, see U.S. Congress, House, Organized Professional Team Sports: Hearings Before the Antitrust Subcommittee of the Committee on the Judiciary. 85th Cong., 1st sess., 1957, 2483–84.

6 Cracker outfielder, team comedian, and team elder statesman Earl “Junior” Wooten came up with the slogan “Operation Ticktock,” and the rest of the players adopted it as their battle cry. See Atlanta Constitution, July 12, 1954; Atlanta Journal, July 13, 1954.

7 For the 1954 Southern Association schedule, I have used The Baseball Blue Book, 1954, 64.

8 Atlanta Constitution, July 7-8, 1954; Atlanta Journal, July 7-8, 1954.

9 Photo of the Torres and caption in Atlanta Constitution, July 9, 1954.

10 Atlanta Journal, July 11, 1954.

11 Atlanta Constitution, July 6 and 9, 1954.

12 This letter is printed in full in Atlanta Journal, July 12, 1954.

13 Atlanta Journal, July 12, 1954.

14 Atlanta Constitution, July 12 -13, 1954.

15 Atlanta Constitution, July 12, 1954.

16 Atlanta Constitution, July 12, 1954.

17 Atlanta Journal, July 12, 1954; Atlanta Constitution, July 12, 1954. In addition to the game reports and commentary, the Journal has a photo sequence of Solt hitting the home run, and the Constitution has a photo of the Crackers greeting Solt at home plate.

18 Atlanta Constitution, July 12, 1954.

19 Atlanta Constitution, July 12, 1954.

20 For seating capacity at Ponce de Leon, I have used The Baseball Blue Book, 1954, 25.

21 Atlanta Constitution, July 16, 1954.

22 Atlanta Journal, July 16, 1954.

23 Atlanta Constitution, November 17, 1954.

24 Atlanta Constitution, July 13, 1954.

25 Clipping, 1956, Jim Solt file, Sporting News Archives; clipping, Atlanta Constitution. July 19, 1958, Charlie Roberts Collection, Atlanta History Center, MS 552, box 12, folder 7; interview with Whitlow Wyatt by Loran Smith (1976), Georgia Sports Hall of Fame Archives; interview with Furman Bisher by the author, February 24, 1999.