Larry Twitchell’s Big Day

This article was written by Brian Marshall

This article was published in Fall 2015 Baseball Research Journal

Larry Twitchell’s greatest day in baseball came on August 15, 1889 — but for many years, it was unclear whether he should share the record for most total bases in a single nine-inning game. This article clears up the mystery. I was researching information related to an afternoon game held on May 30, 1894. Bobby Lowe had four home runs in that game. I came across this line in the Washington Post: “Lowe’s work with the stick was unparalleled, his four home runs making a League record and his total bases equaling Larry Twitchell’s famous record.”

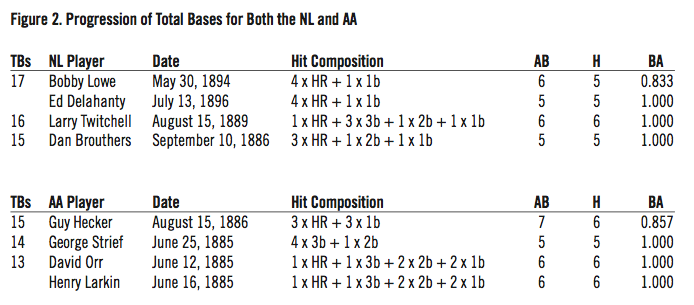

I had been under the impression that Lowe’s 17 total bases was the record for an individual in a single nine-inning game, later equaled by Ed Delahanty, and wasn’t aware that someone had established the mark prior to Lowe. This led me to research the matter and upon further review, it became clear that Twitchell only had 16 bases and not 17. This explains why the major-league record for total bases in a single nine-inning game was listed for many years as being shared by Bobby Lowe and Ed Delahanty, and not by Larry Twitchell.

Larry Twitchell’s big day came on August 15, 1889, in a game between the Cleveland Spiders and the Boston Beaneaters, played at League Park in Cleveland, Ohio.1 The Cleveland Leader described Cleveland native Twitchell as a “good natured and affable young man who rakes flies out of left field” and also “the same Larry who played in every vacant lot in Cleveland in his boyhood days.”

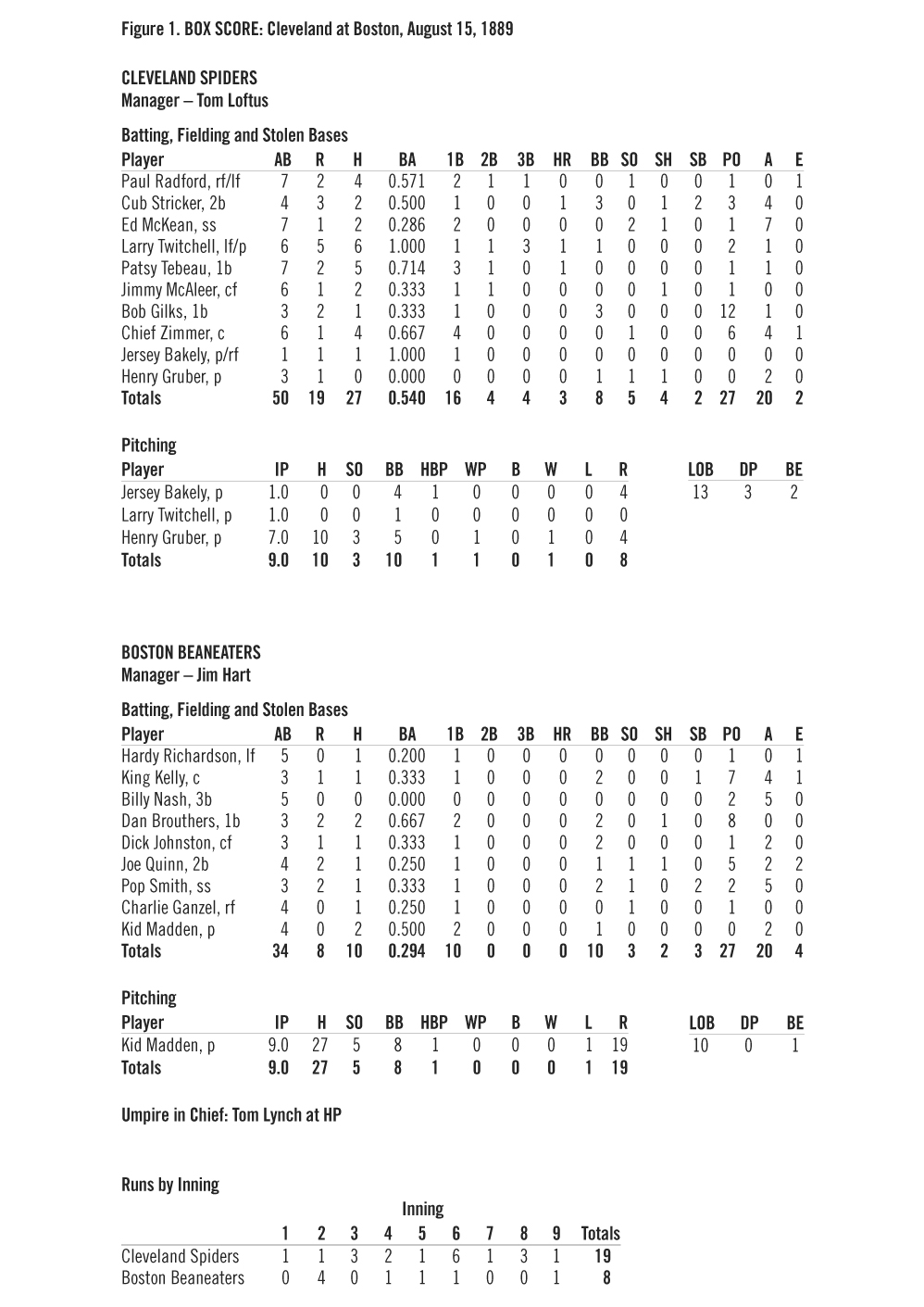

The boxscore in Figure 1 indicates that Larry Twitchell was perfect on the day with a batting average of 1.000 based on his six hits in six at bats with one base on balls for a total of seven plate appearances:

- First Inning – single to left field scoring Stricker, left on base

- Third Inning (led off) – triple up against the left field fence, Twitchell scored on Tebeau’s single

- Fourth Inning – triple to center field scoring Stricker, Twitchell scored on Tebeau’s double

- Sixth Inning (led off) – double to right-center field, Twitchell scored on Tebeau’s single

- Seventh Inning (led off) – home run to left-center field

- Eighth Inning – base on balls, Twitchell scored on Tebeau’s home run

- Ninth Inning – triple to center field, left on base

Figure 1. Click image to enlarge.

When it was all said and done, Twitchell’s six hits were comprised of one single, one double, three triples and a home run for a total of 16 total bases and included hitting for the cycle.

From a team perspective, Cleveland scored in every inning, amassed 27 hits, including 11 extra base hits, and 48 total bases, none of which was an NL record at the time.2 Regarding the Cleveland team effort, The Cleveland Leader said, “Cleveland broke the League batting record for the season and made one of the best records ever made in the history of the organization. Twenty-seven hits for a total of forty-eight bases doesn’t grow on every tree and never grew in Cleveland before, that’s sure.”

The Leader further commented as follows:

“Kid” Madden, the energetic young gum-chewing pitcher of the Bean Eaters, was in the box and was kindly kept there for nine long and enthusiastic innings while the infants fattened up their batting averages, the base hit column was swollen until its own mother wouldn’t recognize it, and the total base column looks like the fat man of the dime museum.

The Twitchell performance on August 15 wasn’t simply limited to his batting and fielding exploits, he also pitched in the game. Twitchell started the game in left field but was called in to pitch in the second inning. Jersey Bakely was the starting pitcher for Cleveland but he walked the first four Boston batters in the bottom of the second and hit the next batter.3 Bakely went to right field, Radford went from right to left, and Twitchell went from left field to pitcher. The first batter that Twitchell faced was Kid Madden, the Boston pitcher, and Twitchell walked him, forcing in another run. Then a hit was muffed by Radford in left field which scored another run, Boston’s fourth in the inning. Ganzel was thrown out at the plate on Kelly’s hit to McKean and Madden was thrown out at the plate on Nash’s hit to Twitchell, who threw to Zimmer, who was also able to throw out Nash at first for a double play. Gruber started the third inning in the box for Cleveland which presumably sent Twitchell back to left field and Radford to right field.

An interesting sideline regarding Twitchell’s big day has to do with the topic of individual total bases. There was misleading information in the published accounts at the time and those after the fact. The 16 total bases registered by Twitchell surpassed the previous NL mark of 15, which was held by Dan Brouthers. In a game played on Friday September 10, 1886, Brouthers, playing for the Detroit Wolverines, had five hits against the Chicago White Stockings: three home runs, one double, and one single. The Twitchell total bases mark also surpassed the record in the American Association (AA), which was also 15, and was also established in 1886.

The AA mark was set by Guy Hecker, a pitcher for the Louisville Colonels, in the second game of a doubleheader played on Sunday August 15, 1886, against the Baltimore Orioles. The Louisville Courier-Journal reported, “Hecker broke all previous batting records for a single game, making three home runs and three singles, a total of six hits which yielded altogether fifteen bases. He was at the bat seven times and made seven scores.”

The Baltimore Sun stated, “The feature of the game was Hecker’s tremendous and unparalleled batting. He made three home runs and three singles, with a total of fifteen bases, which has never been equaled in the history of the national game. Hecker also made seven scores out of seven times at bat.” The Baltimore American agreed: “Hecker made a remarkable record out of seven times at bat. He secured seven runs and five hits, three of them being home runs, and yielding him a total of fourteen bases.”

The American coverage was very misleading because the boxscore listed Hecker with six hits, not five, as they had mentioned in their writeup, and to make matters worse they listed Hecker as having a double in the breakdown below the boxscore. Some simple math based on Hecker having had five hits, as the American stated, comprised of three home runs, a double and a single, would yield a minimum of 15 bases, not 14 as the article had stated. The Baltimore American statistical portion of their coverage is so contradictory, as it related to some of the metrics for Hecker, that it becomes hard to identify what really happened and causes one to wonder what they were basing their information on.

The game write-up in Sporting Life ran as follows: “The afternoon game was remarkable for the wonderful and unprecedented batting of Hecker, who broke the individual batting record for a single game. He was seven times at bat and made three home runs, two doubles and a single. An error gave him a base once, and he scored seven runs, thus beating the record in three different ways—home runs, total bases and number of runs.”

In the breakdown below the boxscore, Sporting Life contradicted themselves by not listing Hecker as having a single double, let alone two doubles.

Regarding Brouthers’s performance of September 10, 1886, the Sporting Life write-up read, “Both clubs hit very hard and Brouthers made a remarkable display, in five times at bat getting five hits for a total of fifteen bases, three of the hits being home runs. This leads the League record and almost equals Hecker’s record of sixteen bases.”

The mention of Hecker’s record being 16 bases is not correct as, apparently, he only had 15 bases in the August 15, 1886, game. It should be pointed out that the Hecker marks for runs scored and home runs in a game by a pitcher are also long-standing major-league records, whereas the total bases mark, while an AA record, was short lived from a major-league perspective.

The story of the total bases doesn’t end with the Hecker AA game in 1886. It actually revealed the omission of a performance by George Strief, in addition to an error in the number of total bases. The Louisville Courier-Journal stated the following:

No Association player ever before made three home runs in a championship game, or reached a total of fifteen bases. The best records were made by Orr, the big batter of the Metropolitans, and Larkin, the heavy slugger of the Athletics. These players tied for the honor, each having made a total of eleven bases last year, Orr against Caruthers, of the St. Louis Browns, and Larkin against Morris, of the Pittsburghs. Hecker’s performance is thus four points better than that of either Orr or Larkin. In the National League, Anson, of Chicago, once made three home runs in a single game, but his total number of bases did not equal Hecker’s record yesterday.

The issue with the preceding, as reported in the Louisville Courier-Journal, is threefold.

- The total bases mark that Hecker surpassed was stated incorrectly as 11 when it was 13.

- The 11 total bases was incorrectly implied as the previous mark. George Strief had established a mark of 14 bases in a single game after both of the Orr and Larkin performances.

- It was incorrectly implied that Anson had the only previous three-home-run performance in a single game. There were at least two others, being Williamson and Manning, both in 1884 along with Anson.

The Orr performance was on June 12, 1885, against the St. Louis Browns at the Polo Grounds. The New York Times reported the game as follows:

The 1,500 persons who attended the Metropolitan-St. Louis game on the Polo Grounds yesterday witnessed a most remarkable feat in batting. It was performed by David Orr, the first baseman of the Mets. He went to the bat six times, and hit the ball safely on each occasion. One of his hits, a line ball to the left field, yielded him a home run; another to the centre field gave him three bases. Besides these he made two doubles and two singles—in all a total of thirteen bases.

The Larkin performance was on June 16, 1885, against the Pittsburgh Alleghenys in Philadelphia. The Philadelphia Record reported it this way:

The Pittsburgh club was beaten to the tune of 14 to 1 by the Athletic nine at the Jefferson Street ground yesterday. Morris, the visiting club’s crack left-handed pitcher was batted for a total of thirtyfour bases, and Larkin, the Athletic Club’s centre fielder, equaled Orr’s great batting record. He was six times at bat and made six safe hits, with a total of thirteen. The first hit was a home run, the second a three-bagger, the third a double, and the fourth a single. Then came another double, and he completed the great record by a clean single in the ninth inning.

Figure 2. Click image to enlarge.

Both David Orr of the Metropolitans and Henry Larkin of the Athletics hit for the cycle, and had the exact same batting statistics which consequently yielded the exact same total bases.

The performance that was completely omitted from the the Louisville Courier-Journal newspaper article covering the Hecker game, and at least one subsequent publication, was that of George Strief of the Athletics on June 25, 1885, in a game against the Brooklyn club in Brooklyn. The importance of the Strief game was that it superseded, from a total bases and date perspective, both the Orr and Larkin performances since Strief registered 14 bases on four triples and a double in five hits and five at bats. Not to mention the fact that the four triples was not only an AA record for the most triples in a single game by an individual, it was also a majorleague record at the time. The game write-up in Sporting Life read, “Strief and Pinckney [sic] hit safely every time they went to the bat. The former made four three baggers and a two bagger, a total of 14 hits [sic], which beats Orr’s and Larkin’s record.”

The New York Times reported as follows: “The contest at Washington Park, in Brooklyn, yesterday, between the Brooklyn and Athletic Clubs, was marked by very heavy batting. Strief, of the Athletics, led in the heavy work. He made four three-base hits and a double.”

In conclusion, the most appropriate way to emphasize the impact of the Twitchell performance on August 15, 1889, is to let the records that he set and/or equaled speak for themselves.

- Set the NL record for most total bases by an individual in a single game with 16. (Previous NL record was 15 total bases by Dan Brouthers on September 10, 1886, with three home runs, one double, and one single in five hits.)

- Equaled the NL record for most extra base hits by an individual in a single game with five. (George Gore, of the NL Chicago White Stockings, had five extra base hits with three doubles and two triples in five hits on July 9, 1885.)

- Equaled the NL record for the most hits by an individual in a single game with six. (NL record was broken by Wilbert Robinson with 7 hits on June 10, 1892 {1}.)

- At the very least equaled, if not set, the NL record for the most triples by an individual in a single game with three. (NL record was broken by Bill Joyce with four triples on May 18, 1897.)4

Honorable mention: Twitchell scored five runs which was one shy of the NL record.

BRIAN MARSHALL is an Electrical Engineering Technologist living in Barrie, Ontario, Canada, and a longtime researcher in various fields including entomology, power electronic engineering, NFL, Canadian Football, and recently MLB. Brian has written many articles, winning awards for two of them, with two baseball books on the way, one on the 1927 New York Yankees and the other on the 1897 Baltimore Orioles. Brian is a long time member of the PFRA. While growing up, Brian played many sports including foot- ball, rugby, hockey, and baseball, and participated in power lifting and arm wrestling events. He aspired to be a professional football player, but when that didn’t materialize he focused on Rugby Union and played off and on for 17 seasons in the “front row.”

Author’s notes

A progression of total bases leaders for both the NL and AA is listed in Figure 2. Team names and the spelling of player names was based on that as listed on Baseball-Reference.com.

Sources

“BOSTON VS CINCINNATI: Home Run Record Broken,” Washington Post, Thursday, May 31, 1894, 6.

“THEY HIT THE BALL: The Giant Killers Give a Wonderful Exhibition of Heavy Batting,” Cleveland Leader, Friday, August 16, 1889, page unknown.

“THEY HIT THE BALL: The Spiders Play Havoc With Kid Madden’s Curves,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, Friday, August 16, 1889, 4.

“ENOUGH FOR ONE DAY: The Louisvilles Win a Game From Kilroy and Another Off Conway: Hecker Breaks the Batting Record With Three Home Runs and Three Singles: Doubling the Dose,” Louisville Courier-Journal, Monday Morning, August 16, 1886, page unknown.

“BASEBALL: The Baltimores Lose Two Games at Louisville on Sunday,” Baltimore Sun, Monday, August 16, 1886, page unknown.

“NOW WITHOUT A CATCHER: The Baltimores Lose on Sunday as Well as Any Other Day: Afternoon Game,” Baltimore American, Monday, August 16, 1886, 4.

“BASE BALL: American Association: Games Played Sunday, Aug. 18,” Sporting Life, Volume 7, Number 20, August 25, 1886, 2.

“BASE BALL: The National League: Games Played Friday, Sept. 10,” Sporting Life, Volume 7, Number 23, September 15, 1886, 4.

“A GREAT FEAT IN BATTING: Orr Hits Caruthers for Thirteen Bases,” The New York Times, Saturday, Jun 13, 1885, 2.

“PITTSBURGH OVERWHELMED: A One-Sided Slugging Game—Larkin Equals Orr’s Great Batting Record,” Philadelphia Record, Wednesday Morning, June 17, 1885, 4.

“THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION: Games Played June 25,” Sporting Life, Volume 5, Number 12, July 1, 1885, 6.

“ON THE DIAMOND FIELD,” The New York Times, Friday, Jun 26, 1885, page 2.

“BASE-BALL: Chicago 31, Buffalo 7,” Chicago Tribune, Wednesday, July 4, 1883, 7.

Bill Felber, Editor. Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century. Phoenix, AZ: Society for American Baseball Research, Inc., 2013.

John B. Foster, Editor (Compiled by Charles D. White). Spalding’s Official Base Ball Record, part of the Spalding “Red Cover” Series of Athletic Handbooks, No. 59R. New York, NY: American Sports Publishing Company, 1924.

John B. Foster, Editor (Compiled by Charles D. White). The Little Red Book: Spalding’s Official Base Ball Record, part of the Spalding’s Athletic Library, No. 59B. New York, NY: American Sports Publishing Company, 1928.

Notes

1 The day was a little cool, given the time of year, with a temperature of about 64°F, the skies were partly cloudy and there was a light breeze from the southwest.

2 There was a game played on July 3, 1883, between the Chicago White Stockings and the Buffalo Bisons in which Chicago registered 32 hits, including 16 extra base hits, 14 of which were doubles, and 50 total bases.

3 The four consecutive batters that were walked by Bakely were Brouthers, Johnston, Quinn, and Smith which forced in a run and the batter that was hit by Bakely was Ganzel which forced in another run.

4 Regarding the three triples, it may have been the NL record at the time. I was unable to find a reference that categorically stated when the single game record for triples by an individual was established prior to the Joyce performance.