Lester B. Pearson: Canada’s Ballplayer Prime Minister

This article was written by Stephen Dame

This article was published in Spring 2020 Baseball Research Journal

The first real job I had after university was working in politics on Ottawa’s Parliament Hill. The job title was “legislative assistant to a Member of Parliament,” but really, I was a grunt. I answered the mail, prepared the propaganda, and greeted visitors to the office. The best part of the gig was the location. As a political history nerd, I was thrilled to be working in and around the century-old Centre Block, the massive gothic-revival home to Canada’s bicameral legislature.

The first real job I had after university was working in politics on Ottawa’s Parliament Hill. The job title was “legislative assistant to a Member of Parliament,” but really, I was a grunt. I answered the mail, prepared the propaganda, and greeted visitors to the office. The best part of the gig was the location. As a political history nerd, I was thrilled to be working in and around the century-old Centre Block, the massive gothic-revival home to Canada’s bicameral legislature.

Touring visiting constituents around that space quickly became one of my favorite duties. A certain visit, on each tour I gave, was to the statue of a fellow baseball fan, Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson. Lester B. sits just outside the House of Commons. Unlike his other immortalized contemporaries, Pearson is depicted seated in his office chair. His statue is angled ever so slightly to stage left. There he sits, overlooking the vast lawns of Parliament Hill. His monument was constructed this way (according to tour guide lore) so that he could watch over the softball and baseball games played on the greenery in front of Centre Block.

Indeed, that spot hosted more than a century of bat and ball games. Members of the press played Members of Parliament in an annual softball affair there. Teams composed of security staffers, federal police, mail clerks, Parliamentary assistants, and even M.P.s skipping out on votes, have all shuffled around the bases in the shadow of the Peace Tower. Pearson was such a baseball nut that those who honored him thought it appropriate his statue be able to observe these baseball games forever. Today Lester B. patiently waits for a game to break out on the very spot where he himself, both as Leader of the Opposition and later as Prime Minister of Canada, played ball. His middle initial stands for “Bowles,” but it may as well have stood for “baseball.” No other prime minister in Canadian history so loved the game or made it such a resonant part of his political brand.

The connections between Pearson and Canada’s original national game are myriad. Just five pages into Pearson’s three volume autobiography, the man himself details an early baseball memory. It is an anecdote in the vein of W.P. Kinsella, wherein grown men link their affection for baseball to the men they loved:

Grandfather Pearson had a particular passion for baseball, a passion inherited by his son, my father, and his grandsons. My last outing with him was on Dominion Day in 1913. He had retired from the ministry; he was frail, aging, and his eyesight had almost gone. The Toronto baseball team, in the old International League, was to play two games, morning and afternoon, on that holiday at the Ball Park at Hanlan’s Point, across Toronto Bay. Grandfather was determined to go, and his son, my uncle Harold, with whom he was then living, agreed. I was happy and excited to escort. I remember we had good seats. It was a good game and my grandfather, who could hardly see the players, let alone the ball, enjoyed it as much as I did.1

The following year, Pearson was playing second base in Hamilton’s City Baseball League while he was working for the municipality. Then, as he put it, his world ended when the world went to war. Pearson enlisted first as a medical orderly with the University of Toronto medical unit. While stationed in Salonika, Greece, he played baseball with his fellow soldiers there. “He was a natural leader, good at baseball,” said his roommate William Dafoe.2 As the war went on, and especially after the arrival of the American troops, baseball became a more and more prominent part of a soldier’s daily life. Teams were organized by battalions, military hospitals, groups of officers, and even prisoners of war. Baseball was played regularly by Canadian soldiers at more than 90 known locations throughout Europe.3 Canadians played on their rest and reserve rotations, sometimes within meters of exploding German shells.4

Games between Canadian and American troops took on a naturally competitive nature. At soccer stadiums and cricket pitches, thousands of locals and servicepeople paid money to watch military men play baseball.5 When asked during an interview for an External Affairs position what his greatest contribution to the war had been, Pearson deadpanned, “my home run at Bramshott [base]” which helped defeat a team of Americans.6

While on leave in London, Pearson looked the wrong way crossing the street and was hit by a bus. He survived the double-decker hit and run, and as a result may have survived the war. He was invalided home. Healed up by the summer of 1919, Pearson was at a loss in terms of direction. “What then, to do? I was restless, unsettled, and had no answers. But it was early summer and I loved baseball. I went to Guelph, the home of not only my parents, but also of a team in the Inter-County League, a very good semi-professional organization.”7 Pearson knew two players on the team from his days playing ball in Hamilton. He walked into the ballpark and walked onto the team. He was given a job at the Partridge Tire and Rubber Company where he “punched the clock and did odd jobs when not playing baseball.”8

When Pearson determined that his path through baseball would not take him to the majors, he began to study for entry into the foreign service. By 1943, he was working for the Canadian government in Washington, DC. In his memoirs, Pearson wrote of the serious nature of baseball games played between the Canadians and Americans in the U.S. capital:

The baseball games which really mattered—apart from those of the Washington Senators in the American League, which I loved to watch whenever I could—were those between the Canadian Embassy and the State Department. We had a reasonably good team, thanks to a few experts from the Canadian military mission. Our diplomatic worry was that we might prejudice our good relations with the [US] State Department by beating them too easily. At the same time national pride would permit no defeat by the foreigner. So we worked out a unique and ingenious way of handicapping. We placed a jug of martinis and a glass at each base and agreed that whenever a player reached a base, he had to drink a martini. This ensured a record number of men stranded on third base and, if anyone did try to make home plate, he could easily be tagged.9

Pearson distinguished himself in the foreign service and at the United Nations. While in New York, he had a “life pass to Ebbet’s Field” to watch the Brooklyn Dodgers play ball.10 In 1957, after leading the peace process to diffuse a potential nuclear war over the Suez Canal, he received the Nobel Peace Prize. While breaking the news to the country, The Globe and Mail referred to him not as a professor, diplomat, or potential Liberal Leader, but as “a 60-year-old baseball fan.”11 Baseball, from the very beginning, was a large part of Pearson’s political identity.

Pearson won the Liberal leadership in January 1958. That spring, he mixed politics with baseball for the first time as Leader of the Opposition. He and Prime Minister John Diefenbaker took part in the Parliamentary Security Service vs. Members of Parliament game on The Hill, as detailed in the preceding article (“First Base Among Equals: Prime Ministers and Canada’s National Game”).

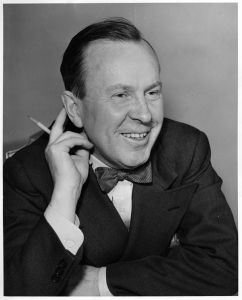

When the election came later in 1958, Pearson barnstormed the country like all politicians, but made a few more stops along the way. His handlers were well aware that his baseball skill could make the bowtie-wearing policy wonk seem more leaderlike. He stopped his campaign caravan in Kingston when he spotted a group of boys playing a game in the yard at St. Patrick’s Catholic School. “Once a semi-pro baseball player, the Liberal leader showed some of the old diamond ability as he got ahold of a pitch. It proved to be one of the most heart-warming receptions of his election tour. When he turned to leave he was given a burst of applause by the children.”12

When the election came later in 1958, Pearson barnstormed the country like all politicians, but made a few more stops along the way. His handlers were well aware that his baseball skill could make the bowtie-wearing policy wonk seem more leaderlike. He stopped his campaign caravan in Kingston when he spotted a group of boys playing a game in the yard at St. Patrick’s Catholic School. “Once a semi-pro baseball player, the Liberal leader showed some of the old diamond ability as he got ahold of a pitch. It proved to be one of the most heart-warming receptions of his election tour. When he turned to leave he was given a burst of applause by the children.”12

In Winnipeg, a reporter noted how Pearson’s speeches were peppered with references to his baseball past. “All through his tour so far, Mr. Pearson has been dogged by snide references to his party’s record during its 23 years as the government. Mr. Pearson’s experience in handling difficult questions at international councils and his youthful experience as a baseball player (to which he frequently refers) stands him well in these instances.”13 Pearson lost the election, but it was only his first strike.

The Toronto Star ran a photo puzzle game shortly after the election whereby the word “Pearson” appeared as a possible answer below a photo of boys playing baseball.14 While praising Canada’s democracy post-election (turnout was 80%), Robert Turnbull wrote in the Globe and Mail that “dictators simply aren’t sportsmen,” before praising Dwight Eisenhower, Harold MacMillan, and Lester Pearson for their athletic pasts. Incorrectly assuming Lester B was done after his 1958 loss, Turnbull wrote, “Lester Pearson’s thrills will now come primarily from watching baseball.”15

The 1962 campaign saw the continued baseball branding of Lester Pearson. At Barry’s Bay, the talk of baseball turned to action on the local diamond. Pearson “missed his first pitch at bat with a Little League baseball team, but blasted the second ball into centre field, over the heads of the 400 district residents, striking the window of a parked car. The window remained in one piece.”16

One of Pearson’s star candidates in 1962 was hockey star Red Kelly. At Coronation Park in Oakville, Ontario, Pearson and Kelly staged a photo-op on the baseball diamond. A stage-managed moment for the cameras occurred when Kelly and Pearson just happened to drop in on the St. Dominic’s junior team as they began a practice. “Terry Houghton, 10, pitched three balls, Mr. Pearson hit one fly, which was dropped, bunted once into a crowd of photographers and was caught by the pitcher on the third ball.”17 The campaign stop was a success. A photo of Pearson up to bat, while Kelly played catcher behind him (both men in full suits) was picked up by newspapers across the country. It became clear during the Oakville stop that Pearson would not be able to make it back to Maple Leaf Stadium in time for his scheduled ceremonial first pitch. “I am not throwing out the first ball in Toronto,” he said. “But it’s not who throws out the first ball, but who hits the last one that really counts.”18 A staffer was asked by a reporter if the opposition leader could afford to miss an appearance before such a crowd. “Mr. Pearson was disappointed. It’s not that he minds so much missing the political opportunity,” said a Liberal spokesperson, “but he is mad about baseball.”19

Pearson made yet another stop at a baseball diamond during the ’62 campaign, this time in Kingston, Ontario. He pitched to Little Leaguers and again succeeded in getting his picture in the papers—what political types call “earned media” today. When he was asked there about his close relationship with US President John Kennedy, Pearson relayed that he had just returned from Washington where he met the President. The meeting was an undeniable political favor from Kennedy. A reporter then asked if the Canadian election was of any importance to Washington. Pearson replied, “the election is of as much consequence as the fact that the Washington Senators have just suffered their 13th straight loss.”20 The baseball-branded Pearson succeeded in dismantling John Diefenbaker’s historic majority in 1962, but did not win enough seats to become prime minister. A year later, another election was called. 1963 also marked the most significant year for baseball and Canadian prime ministers. Baseball would prove to strengthen the relationship between Canada and its largest trading partner, the game factored into an election again, a certifiable baseball nut finally became prime minister and a film of the PM watching a World Series game was deemed too politically damaging to show on television.

The 1963 campaign began, of course, with more baseball messaging from Lester Pearson. On Prince Edward Island he broke out the ballgame metaphors while criticizing Diefenbaker: “Mr. Pearson accused the government of avoiding decisions in an effort to avoid making mistakes. ‘I don’t like a baseball game with no hits, no runs and no errors.’”21 Later in the campaign, a Globe and Mail endorsement noted Pearson’s athletic past: “a man who once played semi-professional baseball, and still retains a lively interest in all competitive sport, doesn’t fit the picture of a scholar loaded down with honours, a Nobel Prize winner.” The editorial went on to note how Pearson grabbed a handful of snow the previous day, packed it tightly, “reared back and pitched it over the heads of the photographers.”22 The Toronto Star endorsement from the ’63 campaign did not shy away from portraying Pearson as a baseball man:

Pearson’s love of baseball, as a fan long after he ceased to play, is the basis of song and story in the External Affairs department. As head of the department, Mr. Pearson had to make frequent trips to Europe. If these journeys happened to coincide with the World Series, he would somehow manage to arrive at a certain capital in Europe where the Canadian ambassador could always be relied upon to have short wave reception of the games.23

All of the baseball ballyhoo finally paid off. Pearson’s Liberals won the 1963 election. A few weeks after taking office, Pearson was invited to join President Kennedy at his family’s summer estate in Hyannis Port, Cape Cod. The two men, acquainted with each other thanks to a White House dinner held for Nobel Prize winners in 1962, “got along like schoolboys.”24 “The President had been told by the American Ambassador, Walton Butterworth, that baseball was a great hobby of mine,” Pearson wrote in his memoirs. “The President may have treated this information sceptically.” What followed was a command performance by Pearson. “The White House Press Corps said they’d never seen anything like it,” wrote the Vancouver Sun. “Pearson talked baseball and radiated confidence and good humour.”25 Pearson himself wrote:

[Kennedy’s aide Dave] Powers was famous for his statistical infallibility on baseball. We discussed batting and earned run averages back and forth with Powers throwing a few curves at me. My answers showed that I knew something about the sport.26

One key exchange in particular led Pearson to bring up the name of Mets reliever Ken MacKenzie. Pearson later explained to reporters that his knowledge of seemingly obscure relief pitchers was augmented by the fact that MacKenzie, “was a Canadian who lived in my constituency. Indeed, I had helped to get him into professional baseball.”27 Pearson wasn’t sure if the Americans and their President had been impressed by his grasp on North American or International Affairs, but he was certain they were impressed by his knowledge of baseball.28 Kennedy and Pearson went on to have—although tragically brief—the best camaraderie between any President and prime minister of the twentieth century.

Pearson not only impressed Kennedy and Powers, he thoroughly won over the American media during his visit. The AP thought Pearson had stolen the show.29 When reporters asked Pearson about his baseball fandom, apparently unaware that he shared a love of the Red Sox with Kennedy, Pearson quipped about his newfound position of power. “I was in the opposition for a long, long time and I developed a certain sympathy for the underdog,” recorded journalist Bill Galt. “Then he flashed a wide grin and added: ‘now I’m a Yankee fan.’ The press corps roared with laughter.”30 Canada’s ambassador to the United States, Charles Ritchie, thought Pearson’s trip south was “tinged with euphoria.”31

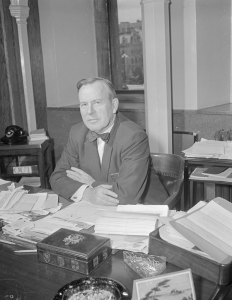

The Indiana Gazette, of all papers, ran a small blurb about the Hyannis Port Summit. They may have taken Pearson’s baseball joke literally. “Canada’s Prime Minister Lester Pearson is, it turns out, quite a baseball fan. He is a fan of the New York Yankees, but the prime minister confided that a generation ago, he liked the Boston Red Sox—Kennedy’s favourite.”32 Back in Ottawa, the prime minister was happy to compete in the press gallery vs. M.P.s softball game. Pearson batted leadoff, connecting for “a solid smash,” and helped the Members of Parliament defeat the press by a score of 9–7.33

Halfway through his term in office, Pearson was asked by Maclean’s Magazine what he would be doing had politics not panned out, “his ambition had been to become a major league baseball manager.”34 During this time, the Liberal Party also agreed to allow a film crew to document the life of the prime minister. The CBC agreed to air the documentary in prime time. The project was conceived as a way to promote the PM ahead of the next election. Instead it turned into a public relations disaster, with baseball playing a very prominent role. “A shoulder camera and microphone followed the prime minister for days producing some intimate shots of Mr. Pearson’s unguarded moments.”35 One of these moments included Pearson intently watching a midday baseball game. The film showed Pearson with his feet up on a chair, eating lunch and watching a World Series game on October 7, 1963. The Yankees were playing the Dodgers. The sounds of the Star Spangled Banner, and later Vin Scully’s voice, could be heard echoing through the prime minister’s office. When cabinet minister Allan J MacEachen entered to speak with the PM, Pearson was clearly distracted by the game, even apologizing for such. According to the producer of the film, the CBC broadcast was scuttled by disapproving Liberal staffers, a charge Pearson had to vigorously deny in the House. The national broadcaster stated that the film did not meet its standards for quality.36 The film didn’t air on television until after Pearson had left office.

When it came time to retire, Pearson provided us a link between Canada’s baseball prime minister, and Shoeless Joe, Canada’s baseball book:

When Prime Minister Lester Pearson announced he would retire, one of the first telegrams came from New York Times columnist James Reston, who cabled: ‘say it isn’t so, Mike.’ Pearson met Reston here last night and the writer asked if the Prime Minister had gotten the allusion. Reston said it was the lament of a little boy to Babe Ruth, when the home-run king announced he was hanging up his spikes. Pearson, an old baseball fan, corrected Reston: ‘It’s what a little boy said to Shoeless Joe Jackson in 1919.’37

“Politics isn’t always sporting,” Pearson said in an exit interview to the Globe and Mail. “You know the man who said ‘nice guys finish last?’” he asked reporter Dick Beddoes. “Leo Durocher?” responded the scribe. “Yes, Durocher,” continued the outgoing PM, “well two years after that he finished last, and he was gone from the Dodgers.”38

John McHale, general manager and vice president of the new Montreal team in the National League, was the first to offer Pearson a retirement gift. The Toronto Star reported that the former Prime Minister was to be named honorary president of the Montreal Voyagers.39 While they had the name of the team wrong, they were correct on the position. Amid rumours in 1968 that he would be taking over the World Bank, Lester Pearson was named honorary president of the Montreal Expos instead. He did in fact take a role with the bank later that year, but it was the baseball job which he mentioned to journalist Frank Jones. “As a boy, I wanted to get into big league baseball, and now I’m honourary president of the Montreal baseball club.”40 On April 14, 1969, it was Pearson, before 29,000 fans at Jarry Park, who went to the mound to toss the first ceremonial pitch in Expos history.41

Nearer the end of his life, Pearson was still attending baseball games:

The Pearsonian sense of humour would be on display in 1970, after he had an eye removed because of a malignant tumor. Pearson went to a Montreal Expos game and met umpire Al Barlick before the contest. “How are you?” asked the ump. “I’m fine,” Pearson replied. “But I’ve recently had an operation that qualifies me for your business… I had my eye out.”42

More than fifty years since Pearson left office, Canada is down to one major league club, but sandlots, gravel infields, and beautifully manicured diamonds continue to fill each summer with young ballplayers eager to hit, throw, and catch. On the lawn in front of Centre Block, Frisbee and soccer kick-arounds are more common now, but the occasional game of catch can still be observed. Remaining among us, from sea to sea to sea, are those who share Lester Pearson’s passion for the game of baseball. And if, by chance, you ever find yourself in Ottawa, walking across the old baseball grounds known as Parliament Hill, be sure to stop by and tip your cap to the statue of Lester B. Pearson, Canada’s ballplayer prime minister.

STEPHEN DAME is a teacher of Humanities in Toronto. He is a member of the Hanlan’s Point chapter of SABR and has presented research papers at three of the four Canadian Baseball History Conferences which take place each November in London, Ontario, Canada.

Sources

Baseball Obscura Blog. Accessed via: medium.com. Available at: https://medium.com/@BaseballObscura/that-time-toronto-almost-joined-the-national-league-in-1886-30c4fd46c306

Borins, Sara, ed. Trudeau Albums. Penguin. Toronto, 2000.

Boyko, John. Cold Fire: Kennedy’s Northern Front. Knopf Canada. Toronto, 2016.

Canada, Government of. Media Advisory. Prime Minister to Meet Canadian Little League

Champions. November 2, 2004. Accessed via Canada.ca. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/news/archive/2004/11/prime-minister-meet-canadian-little-league-baseball-champions.html

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Accessed via cbc.ca. Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/

Calgary Herald. Accessed via newspapers.com. Available at: https://www.newspapers.com/

Chicago Tribune. Accessed via newspapers.com. Available at: https://www.newspapers.com/

Chrétien, Jean. Jean Chrétien; My Stories My Times. Random House. Toronto, 2018.

Chrétien, Jean. Reflections on my Years as Prime Minister. January 30, 2008. Accessed via mystfx.ca. Available at: https://www2.mystfx.ca/political-science/reflections-my-years-prime-minister

Cohen, Andrew. Extraordinary Canadians: Lester B. Pearson. Penguin. Toronto, 2008.

Columbia Broadcasting System Sports. Accessed via cbssports.com. Available at: https://www.cbssports.com

Dame, Stephen. Batted Balls and Bayonets: Baseball and the Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914-1918. Available at: http://baseballresearch.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Dame17.pdf

Diefenbaker, John. One Canada: Memoirs of The Right Honourable John G. Diefenbaker, Volume 1: The Crusading Years. Macmillan. Toronto, 1975.

Donaldson, Gordon. Breaking The Mould in Maclean’s Magazine. April 6, 1998.

Eastern Morning News. Accessed via newspapers.com. Available at: https://www.newspapers.com/

The Evening Standard. Accessed via newspapers.com. Available at: https://www.newspapers.com/

Finkel, Alvin and Conrad, Margaret, eds. History of the Canadian Peoples – 1867 to the Present.

Cultural Currents in the industrial Age. Addison, Wesley, Longman, Toronto, 2002.

Finkel, Alvin and Conrad, Margaret, eds. History of the Canadian Peoples – 1867 to the Present. Interwar Culture. Addison, Wesley, Longman, Toronto, 2002.

Francis, R. Douglas and Smith, Donald B, eds. Readings in Canadian History – Post Confederation. Idealized Middle Class Sport For a Young Nation. Nelson. Calgary, 2002.

The Globe and Mail. Accessed via Toronto Public Library Archive. Available at: https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDMEDB0057&R=EDB0057

Gwyn, Richard. John A. : The Man Who Made Us. The Life and Time of John A. Macdonald. Random House. Toronto, 2007.

The Indiana Gazette. Accessed via newspapers.com. Available at: https://www.newspapers.com/

The Iodine Chronicle. Play Ball. June 15, 1916.

Levine, Allan. King: A Life Guided by the Hand of Destiny. Dundurn Press. Toronto, 2012

Levine, Allan. Scrum Wars: The Prime Ministers and the Media. Dundurn Press. Toronto, 1996.

London Advertiser. Accessed via the British Newspaper Archive. Available at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/

Long Branch Daily Record. Accessed via newspapers.com. Available at: https://www.newspapers.com/

Martin, Lawrence. Chrétien. Lester Publishing. Toronto, 1995.

Martin, Paul. Quoted on Power and Politics on the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. June 6, 2018.

Montreal Gazette. Accessed via newspapers.com. Available at: https://www.newspapers.com/

New York Tribune. Accessed via newspapers.com. Available at: https://www.newspapers.com/

Ottawa Citizen. Accessed via newspapers.com. Available at: https://www.newspapers.com/

The Ottawa Journal. Accessed via newspapers.com. Available at: https://www.newspapers.com/

Paikin, Steve. Fifty Years Ago This Week, Lester Pearson Became Prime Minister. April 10, 2013. Accessed via tvo.org. Available at: https://www.tvo.org/article/fifty-years-ago-this-week-lester-pearson-became-prime-minister-part-i

Pearson, Lester B. Mike: The Memoirs of the Rt. Hon. Lester B. Pearson, Volume One 1897-1948. University of Toronto Press. Toronto, 1973.

Pearson, Lester B. Mike: The Memoirs of the Rt. Hon. Lester B. Pearson, Volume Three 1957-1968. University of Toronto Press. Toronto, 1973.

Prince George Citizen. Accessed via newspapers.com. Available at: https://www.newspapers.com/

Province of Canada. Accessed via provinceofcanada.com. Available at: https://provinceofcanada.com

Sportsnet. Accessed via sportsnet.ca. Available at: https://www.sportsnet.ca

Stewart, J.D.M. Being Prime Minister. Dundurn Press. Toronto, 2018.

Toronto Life Magazine. Accessed via torontolife.com. Available at: https://torontolife.com/city/toronto-politics/harper-ignatieff-baseball-moments/

Toronto Star. Accessed via Toronto Public Library Archive. Available at: https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDMEDB0111&R=EDB0111

Total Pro Sports. Accessed via totalprosports.com. Available at: https://www.totalprosports.com

United States of America, Government of. Media Release. Remarks by President Obama and Prime Minister Trudeau of Canada. Mar 10, 2016. Accessed via ca.usembassy.gov. Available at: https://ca.usembassy.gov/remarks-by-president-obama-and-prime-minister-trudeau-of-canada-at-arrival-ceremony/

Vancouver Sun. Accessed via newspapers.com. Available at: https://www.newspapers.com/

The Windsor Star. Accessed via newspapers.com. Available at: https://www.newspapers.com/

Notes

1 Lester B. Pearson, Memoirs of the Right Honourable Lester Pearson. Vol 1. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1972: 5.

2 Peter C. Newman, “Pearson: A Good Man In a Wicked Time,” Toronto Daily Star, December 16, 1967, B7.

3 Stephen Dame, “Batted Balls and Bayonets: Baseball and the Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914-1918.” Centre for Canadian Baseball Research. Last modified November, 2017. http://baseballresearch.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Dame17.pdf

4 Dame, “Batted Balls and Bayonets.”

5 Dame, “Batted Balls and Bayonets.”

6 Dame, “Batted Balls and Bayonets.”

7 Lester B. Pearson, Memoirs of the Right Honourable Lester Pearson. Vol 1. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1972: 40.

8 Pearson, Memoirs.

9 Pearson, Memoirs.

10 Ken McKee, “Pearson the fan, Player,” Toronto Daily Star, December 15, 1967, 16.

11 Canadian Press, “Pearson Says Award Tribute To Canada,” The Globe and Mail, October 15, 1957, 10.

12 “Pearson Demonstrates Baseball Skill, Thrills Children,” The Toronto Daily Star, March 29, 1958, 3.

13 William Kinmond, “Transition,” The Globe and Mail, March 6, 1958, 23.

14 “Sample Puzzle No. 3,” Toronto Daily Star, May 14, 1959, 19.

15 Robert Turnbull. “Political Gamesmanship,” The Globe and Mail, January 3, 1959, A11.

16 Walter Gray, “Hundreds Cheer Pearson in PC Stronghold,” The Globe and Mail, May 26, 1962, 9.

17 Stanley Westall, “Kelly Outdraws Fastest Liberal Gun,” The Globe and Mail, May 10, 1962, 10.

18 Westall, “Kelly Outdraws Fastest Liberal Gun.”

19 “Maple Leafs Fan Pearson,” The Globe and Mail, May 9, 1962, 1.

20 “Caroline Puzzled,” The Globe and Mail, May 1, 1962, 9.

21 Bruce Macdonald, “Pearson or Paralysis, Liberals Note,” The Globe and Mail. March 21, 1963, 1.

22 Ralph Hyman, “Still a Reasonable Man,” The Globe and Mail, April 10, 1963, 7.

23 John Bird, “The Bird View,” Toronto Daily Star, April 22, 1963, 7.

24 John Boyko. Cold Fire: Kennedy’s Northern Front. Toronto: Knopf Canada, 2016, 156.

25 Bill Galt, “Pearson Scores a Homer,” The Vancouver Sun, May 11, 1963, 1.

26 Lester B. Pearson, Memoirs of the Right Honourable Lester Pearson. Vol 1. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1972: 101.

27 Pearson, Memoirs, 101. Pearson’s memoirs contain a much-repeated anecdote that he, Kennedy, and Powers discussed a game “in Detroit” in which Canadian Ken MacKenzie pitched in relief. Since MacKenzie was with the Mets, Detroit seems an unlikely location for the game. The anecdote is repeated often without questioning this erroneous detail.

28 Pearson, Memoirs, 101.

29 Bill Galt, “Pearson Scores a Homer,” The Vancouver Sun, May 11, 1963, 1.

30 Galt, “Pearson Scores a Homer,”

31 John Boyko. Cold Fire: Kennedy’s Northern Front. Toronto: Knopf Canada, 2016, 156.

32 Newspaper Enterprise Association, “Baseball’s Lure Beyond U.S. Borders,” The Hagerstown Daily Mail, May 25, 1963, 14.

33 United Press International, “A Hit!” Long Branch Daily Record, August 5, 1963, 8.

34 Peter C. Newman, “The Unhappy Warrior,” The Ottawa Journal, March 23, 1965, 7.

35 Canadian Press, “Lester Pearson, his Life and Times,” The Windsor Star, December 28, 1972, 18.

36 “Lester Pearson, his Life and Times.”

37 Robert Reguly, “It Wasn’t So: Pearson Puts Record Straight,” Toronto Daily Star, December 29, 1967, 2.

38 Dick Beddoes, “Pearson Outdistances His Rivals,” The Globe and Mail, April 6, 1968, 41. Pearson engaged in a bit of political hyperbole there: The Dodgers never finished last under Durocher.

39 “Montreal Voyages Into Baseball,” Toronto Daily Star. August 14, 1968, 16.

40 Frank Jones, “Pearson letter to bank’s chief led to new job,” Toronto Daily Star. August 20, 1968, B1.

41 Elizabeth Swinton, “This Day In Sports History: First MLB Game Played Outside Of The U.S.,” Sports Illustrated, last modified April 14, 2020, https://www.si.com/mlb/2020/04/14/this-day-sports-history-first-mlb-game-played-outside-us-montreal

42 J.D.M. Stewart. Being Prime Minister. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2018, 159.