Los Cubanos in New York’s October: An Overview of Cubans in the Postseason for New York-based Clubs

This article was written by Reynaldo Cruz Díaz

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Big Apple (New York, 2017)

Playing in the postseason is high stress and tension-packed, bringing ballplayers to the edge, making them play harder and sometimes better, sometimes making mistakes along the way. The idea of reaching the postseason in New York City—the Capital of Baseball—brings an extra burden for players, even more with the hard-core rivalries like the New York Giants versus the Brooklyn Dodgers or the New York Yankees, or the Yankees versus the Dodgers. When the players come from small towns in the long-isolated island of Cuba and find themselves in crucial baseball games played in the Big Apple, the pressure is further magnified. Every move in New York is scrutinized by the media. And now we will scrutinize some of those players ourselves. from Adolfo Luque (known to fans stateside as Dolf Luque), the first ever Cuban to see postseason action in a New York uniform, to Yoenis Céspedes, the most recent. Whether in the spotlight with classy demeanor, appearing with one brilliant intervention, or withering their performance to oblivion, guys from the Greater of the Antilles have honored the Yankees, Mets, Dodgers, and Giants with postseason appearances.

Playing for Troy and the Mutuals of the National Association, Esteban Bellán was the first Latino to sign a contract for professional baseball in 1871. That also made him the first Cuban to play baseball for a New York-based club, even though the major leagues were not in existence yet, nor were playoffs/postseason as we know them today.

In 1917, in the twilight of an injury-plagued career that included a .317 batting average for the Cincinnati Reds in 1912 and a couple of adventures in the Federal League with the St. Louis Terriers, Armando Marsáns—one of the two first Cubans to don major league uniforms, along with Rafael Almeida—was traded by the St. Louis Browns to the New York Yankees. With that trade, the talented outfielder earned the distinction of being the first Cuban to play for the Yankees, although he was preceded to the city by Emilio Palmero and José Rodríguez (who debuted for the New York Giants in 1915 and 1916, respectively). Marsáns’s biggest distinction is that of being the top holder in hits among Cubans who have worn the pinstripes with 49.

But none of these three players made it to the playoffs while in New York. Marsáns played two seasons in which the American League pennant was won by the White Sox (1917) and the Red Sox (1918), both eventual World Series champions; Palmero’s Giants finished last in 1915. Joined by Rodríguez in 1916, they finished 7 games behind the pennant-winning Dodgers. Rodríguez didn’t see any Fall Classic action when his Giants lost to the White Sox in 1917, before finishing second—10½ games from the Cubs—in 1918.

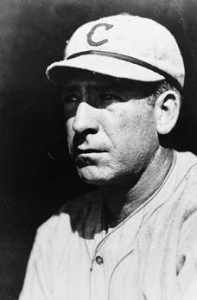

Therefore, the first postseason appearance by a Cuban in the Big Apple was by none other than the aforementioned Adolfo Luque. Luque had been a successful pitcher for the Cincinnati Reds, and he was with them when they won the infamous 1919 World Series against the Chicago White Sox when eight (or fewer) players threw the World Series and became known as the Black Sox. While roaming the bullpen of the Polo Grounds for the Giants in the 1933 World Series against the Washington Senators, he was in the decline of a rather successful 20-year career in which he amassed 194 wins, including 27 in 1923 alone.

Therefore, the first postseason appearance by a Cuban in the Big Apple was by none other than the aforementioned Adolfo Luque. Luque had been a successful pitcher for the Cincinnati Reds, and he was with them when they won the infamous 1919 World Series against the Chicago White Sox when eight (or fewer) players threw the World Series and became known as the Black Sox. While roaming the bullpen of the Polo Grounds for the Giants in the 1933 World Series against the Washington Senators, he was in the decline of a rather successful 20-year career in which he amassed 194 wins, including 27 in 1923 alone.

In the deciding game five, played on October 7 in Griffith Stadium, Luque came in to relieve Hal Schumacher in the sixth inning with two outs, after the Giants’ starter had yielded a three-run shot to Fred Schulte, and two more singles that put runners on first and second. The Pride of Havana retired Luke Sewell on a grounder to second to end the inning, and allowed two hits (both to Joe Cronin in the eighth and the tenth) and two walks while striking out five Senators—three of them in the seventh frame. At the plate, he singled in his lone at bat, off Jack Russell in the top of the ninth. The run that decided it all came on a home run by Mel Ott off Russell in the top of the tenth inning. Luque’s 4.1 innings of work made him the winning pitcher in the game.

Nineteen years would pass before another Cuban made the postseason, and it was with the other New York franchise that would soon relocate to the West Coast. The year was 1952, and outfielder Edmundo Amorós (known in the States as Sandy) was wearing Dodger blue, playing for Brooklyn against the Yankees, appearing in just one game with no plate appearance.

On October 4, 1955, however, Sandy played a pivotal role in the Fall Classic when the Dodgers were taking on the Yankees. Writes SABR researcher Rory Costello, “His racing catch off Yogi Berra near the left-field line at Yankee Stadium saved the Bums’ 2–0 lead in Game Seven of the World Series. Johnny Podres held on for the remaining three innings to bring Brooklyn its only title. The grab by Amorós still stands as one of the greatest in Series history, and it was the defining moment of the Cuban’s career.”1

On October 4, 1955, however, Sandy played a pivotal role in the Fall Classic when the Dodgers were taking on the Yankees. Writes SABR researcher Rory Costello, “His racing catch off Yogi Berra near the left-field line at Yankee Stadium saved the Bums’ 2–0 lead in Game Seven of the World Series. Johnny Podres held on for the remaining three innings to bring Brooklyn its only title. The grab by Amorós still stands as one of the greatest in Series history, and it was the defining moment of the Cuban’s career.”1

The catch was indeed crucial for Brooklyn, but it was not Amorós’s only feat that postseason. He went 4-for-12 at the plate, with three runs scored, a home run, three RBIs and four walks, for a 1.113 OPS. His plate prowess during that World Series was slightly overlooked because of the game-saving grab. Amorós was celebrated as a hero in Cuba, and over half a century later his crucial fielding is still remembered, even long after the Dodgers moved westward to Los Angeles.

Amorós was honored by a Day in his name in Brooklyn on June 20, 1992. Sadly, he never made that trip because he was hit by pneumonia on June 16 and died eleven days later. Amorós also holds the distinction in Cuba of being one of the first Afro-Cubans to gain “international exposure.” As Costello writes about the sixth Central American and Caribbean Games in 1950 in Guatemala City, “Cuba won all seven of its games in the eight-team baseball tournament—led by Amorós, who hit .370 with six homers and 14 RBIs.”2

The move to the Pacific Coast by the Giants (to San Francisco) and the Dodgers (to Los Angeles) caused a drought of Cubans in the big city, as only the Yankees were left, and when the Mets came along in 1962 they were far from competitive. Their first Cuban player turned out to be Humberto “Chico” Fernández, who came mid-season from the Detroit Tigers in only the franchise’s second season.

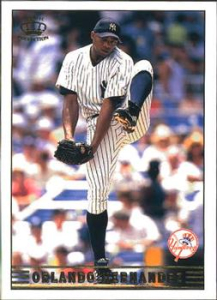

In 1998, long after Amorós had passed away, another player from the island nation made his way to the playoffs wearing a New York uniform, this time with the Yankees. Orlando Hernández, known to Cubans (and New Yorkers) as “El Duque,” defected from the island following his brother Livan’s defection and his own subsequent falling into disfavor with the Cuban authorities. One year earlier, Liván had won World Series Most Valuable Player plaudits while bringing the first title to the Florida Marlins as a rookie.

Without no appearance in the American League Division Series, El Duque started game four of the AL Championship Series on October 10 against the Cleveland Indians and went seven shutout innings, allowing only three hits, striking out six and walking only two. Then, in game two of the World Series against the San Diego Padres, the 32-year-old rookie threw seven frames with six hits, one earned run, seven strikeouts, and three walks, helping the pinstripes sweep the Fall Classic in four games.

Those turned out to be golden years for the Joe Torre-managed and Derek Jeter-led Yankees, as they won the World Series three consecutive seasons, from 1998 through 2000, and El Duque took part in all of them. He also went scoreless in his first ALDS game. Following his great success during the 1999 regular season, he was given the call in game one on October 5 and he went eight shutout frames, with only two hits, six walks, and four strikeouts against the Texas Rangers. In the ALCS he again got the game one nod against the Red Sox on October 13, but despite going eight strong innings of three runs (one unearned), seven hits, two walks, and four strikeouts, received a no-decision when the Yankees won, 4–3. In game five, played in Fenway Park five days later, Hernández threw seven-plus innings of one-run ball, allowing just five hits (including a round-tripper by Jason Varitek in the eighth) with four walks and nine batters fanned. Thanks to that performance, he was voted the ALCS most Valuable Player.

In the Fall Classic, on October 23 as the game one starter, he checked the box again, winning his lone game against the Atlanta Braves and eventual Hall of Famer Greg Maddux. As a starter, he had arguably his best postseason outing, pitching seven frames with one hit (Chipper Jones’s home run in the fourth inning), one run, two walks and ten strikeouts.

Hernández had yet another convincing outing in the 2000 Division Series against the Oakland A’s. He won game three by throwing seven strong frames with four hits, five walks, and four strikeouts, allowing two runs; and then got a hold on game five allowing one hit and getting one out. In the League Championship Series, he was not so dominant, as his ERA was 4.20 (seven earned runs in 15 innings), but he won both his starts against the Seattle Mariners, 7–1 and 9–7.

In the first Subway Series played in New York since the 1950s, El Duque had his last Fall Classic decision, losing his lone start against the Mets on October 24. In 7.1 innings of work, he gave up nine hits and four earned runs while walking three and striking out 12.

In each playoff series the following season, El Duque (having his worst regular season with the pinstripes, with a 4–7 record and 4.85 ERA) got a start and went 1–1, beating the A’s in the ALDS, falling to the Mariners in the ALCS, and getting a no-decision in his last World Series start, in game four against the Arizona Diamondbacks, throwing 6.1 innings while yielding four hits, four walks, and one run (on a home run by Mark Grace), while plunking two batters. The Yankees would tie the game in the ninth inning thanks to a home run by Tino Martínez, and would walk the game off in the tenth frame with Derek Jeter’s blast. However, the team all of America was rooting for—following the terrorist attacks against the World Trade Center on 9/11—lost the series in seven games on a ninth inning blown save by Mariano Rivera and a bases-loaded walk-off bloop single by Luis González, an outfielder with Cuban ancestry. That World Series also marked the end of the almost invincible Bronx Bombers, who ruled all of baseball under the helm of Joe Torre.

The crafty Cuban would make it to the postseason again in a Yankee uniform in 2002, but his performance was well past his best: he entered in the fourth inning of game two of the ALDS trailing by three runs against the Anaheim Angels and pitched four innings, but allowed two solo home runs and was charged with the loss, 8–6. In game four he threw 2.1 frames in relief, entering in the fifth with two outs, when New York was down by seven tallies.

After missing 2003 due to a rotator cuff injury in his shoulder that required surgery—he had been traded to the Montreal Expos in the offseason but returned to New York prior to Opening Day in 2004—El Duque had yet another postseason start, his last playoff game as a Yankee. This time he faced the Boston Red Sox in game four of the ALCS, played on October 17 at Fenway Park. He left the game after five innings, allowing three runs and three hits, while walking five and striking out six. The Red Sox would tie the game in the ninth, avoid the sweep (the Yankees were ahead in the Series 3–0 at the time) and eventually put up the greatest comeback in postseason history, going on to win three more games as well as sweeping the St. Louis Cardinals in the Fall Classic.

Perhaps, what is most remarkable about Orlando Hernández was the fact that his major league debut came when he was already 32, and he managed to win nine postseason games and lose only three, all decisions as a Yankee. In 102 innings of postseason work, he struck out 101 opponents, gave 51 free passes and had an ERA of 2.65, whereas his WHIP was 1.245 in 17 games—14 starts. It is also important to note that he had a 2–1 record in four World Series, of which New York won three. Perhaps his ability of working well under pressure is explained in Peter C. Bjarkman’s words about him and his half-brother, Liván Hernández: “One colorful rookie-season incident that has become legend has Hernández questioned by New York media about the pressures of first facing the Red Sox and Pedro Martínez in ‘The House That Ruth Built.’ [It would have been the game of September 14, in which Duque tossed a three-hit shutout.] El Duque is reported to have laughed off the question by responding that no pressure could compare to what he had already known pitching against rival Santiago de Cuba with 50,000 fanatics crammed into Havana’s Latin American Stadium.”3

Perhaps, what is most remarkable about Orlando Hernández was the fact that his major league debut came when he was already 32, and he managed to win nine postseason games and lose only three, all decisions as a Yankee. In 102 innings of postseason work, he struck out 101 opponents, gave 51 free passes and had an ERA of 2.65, whereas his WHIP was 1.245 in 17 games—14 starts. It is also important to note that he had a 2–1 record in four World Series, of which New York won three. Perhaps his ability of working well under pressure is explained in Peter C. Bjarkman’s words about him and his half-brother, Liván Hernández: “One colorful rookie-season incident that has become legend has Hernández questioned by New York media about the pressures of first facing the Red Sox and Pedro Martínez in ‘The House That Ruth Built.’ [It would have been the game of September 14, in which Duque tossed a three-hit shutout.] El Duque is reported to have laughed off the question by responding that no pressure could compare to what he had already known pitching against rival Santiago de Cuba with 50,000 fanatics crammed into Havana’s Latin American Stadium.”3

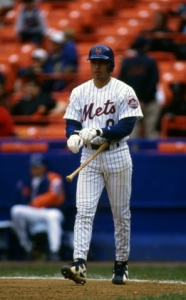

While the former Industriales star—the Cuban League’s all-time record holder in winning percentage—was shining in the Bronx, another Cuban was making his way in Queens, wowing the crowds with his glove, and reaching the postseason in 1999. It was no other than defensive-whiz shortstop Rey Ordóñez, who had the opportunity of becoming the first Cuban to play in the postseason for the New York Mets.

Ordóñez, who had defected from the Cuban College Squad in Buffalo in 1993, came up as a weak-hitting, highly regarded defensive shortstop. He would be a three-time Gold Glove recipient with the Mets, and made his postseason debut on October 5. He would go on to play all games of the National League Division Series against Arizona and the National League Championship Series against the Atlanta Braves.

Ordóñez, who had defected from the Cuban College Squad in Buffalo in 1993, came up as a weak-hitting, highly regarded defensive shortstop. He would be a three-time Gold Glove recipient with the Mets, and made his postseason debut on October 5. He would go on to play all games of the National League Division Series against Arizona and the National League Championship Series against the Atlanta Braves.

The Havana-born infielder participated in ten games, four in the NLDS and the other six in the NLCS, with five hits in 38 at bats, for a .132 batting average. He hit a double (his only postseason extra-base hit) and stole one base in game two against the D’Backs. He scored a run and had an RBI in game one of that series and drove in another one in game three. Against the Braves, he got only a single in 24 at bats, and his OPS for the entire postseason was a weak .289. But not much more can be expected from a guy who batted .246 for life with 12 career dingers in 973 games. He would miss the 2000 postseason, including the Subway Series, after a left arm fracture on May 29, which hampered his fielding for the rest of his career. There was another Cuban on that roster, who never saw action in the postseason: first baseman Jorge Luis Toca.

The Yankees would soon have another Cuban on the mound. Unlike El Duque, who relied on his crafty deliveries and wit, José Ariel Contreras—who defected at age 30 following the 2002 National Series season in Cuba—was considered the island’s top pitcher at the time. Having achieved a status of nearly invincible in Cuba, the tall, black righty from Pinar del Río was usually given the ball by Team Cuba managers for do-or-die games, and he came through.

With the hope that success both in Cuba and the international arena—basically against pros—would translate into big-league success, the New York front office signed him and Contreras responded by going 7–2 with a 3.30 ERA in 71 innings of work that season. But management did not have enough confidence in him to let him start in the postseason, and he would pitch four relief games in the ALCS against the Boston Red Sox, losing one. In the World Series against the Florida Marlins, he also pitched four games out of the bullpen and also lost his only decision.

Contreras would not last long with the Yankees and parted ways with the team midseason in 2004. He wound up with the Chicago White Sox, and helped them—teaming up with El Duque—conquer the World Series in 2005, winning his lone start.

Then along came Yoenis Céspedes, the Granma outfielder who caught scouts’ eyes while playing in the 2009 World Baseball Classic and then went on to set a single-season home run record in the Cuban National Series prior to his defection. Céspedes signed with the Oakland A’s, making his major league debut in 2012. After being traded to the Boston Red Sox midseason in 2014, and then to the Detroit Tigers in that very offseason, the talented Cuban player moved to the New York Mets before the 2015 trade deadline. He instantly exploded and became a sensation, hitting 17 dingers in just 57 games, helping the club reach the postseason with his .942 OPS after the transaction.

With ten previous postseason games under his belt (all with Oakland), Céspedes had a lackluster start with the Mets in Dodger Stadium. His first game in the NLDS could not be more disastrous, as he went 0-for-4 with three strikeouts (two of them against Dodgers ace Clayton Kershaw). But he would hit a blast in the next game, and on October 12, his playoff home debut in Citi Field, he would prove to the Mets he was worth his money, going 3-for-5 with three runs and a three-run home run off reliever Alex Wood.

After getting a single in four at bats on October 13, Céspedes would have exactly the same outcome he had had in game one (zero hits in four at bats with three strikeouts), this time victimized by Zack Greinke, who in three times up fanned him twice. Two days later, the Mets took the series.

Against the Chicago Cubs in the NLCS, Céspedes had a particularly good performance in game three, getting three hits in five at bats, with a double, a run and two RBIs. He batted in the first Mets run in the top of the first inning, with a double off Kyle Hendricks that drove in David Wright. With the game tied, 2–2, he singled in the sixth frame, moved to second on a sacrifice bunt by Lucas Duda, stole third, and scored on a third-strike wild pitch by Trevor Cahill to Michael Conforto. Yoenis would then drive in the first of two insurance runs in the seventh, with a single that sent Wright to the plate.

He would get only three hits and an RBI in the five World Series games against the eventual champions, the Kansas City Royals. Céspedes’s fielding doubts also helped Alcides Escobar get an inside-the-park home run in the first game—a game that would go to extra innings and would be won by the Royals.

In 2016, Céspedes had only one playoff game, this time the Wild Card game against the San Francisco Giants, who had Madison Bumgarner on the mound. The superior lefty would go the distance, blanking the Mets with only four hits and six strikeouts (two of them by the Cuban).

Yoenis has shown, the same as he did in Cuba, incredible performance deficits in the postseason.4 His October numbers for the Mets are well below his proven quality: a .207/.217/.328 line with a meager .544 OPS, 19 strikeouts, 12 hits, and two home runs with eight RBIs are numbers he can actually improve in the near future. If the Mets starting rotation can stay impressive, the team could reach many postseasons in the coming years; Céspedes is under contract until 2020.

Another Cuban who is under contract for a New York-based club currently is Aroldis Chapman. The big lefty, whose fastball has been clocked at over 105 miles per hour, was credited with the win in the last game of the 2016 World Series for the Chicago Cubs, and then returned to the Yankees, this time on a deal that goes as far as 2021—although he may opt out after the 2019 campaign. The Bronx Bombers, out of the postseason since losing in the 2015 Wild Card game to Dallas Keuchel and the Houston Astros, have a young team and have been rebuilding the franchise, so the future looks bright for them and for Chapman.

Only the Mets have won a World Series among New York teams without a Cuban in their roster. The Giants and the Dodgers had indeed important interventions from Cubans in deciding games, and the Yankees had in Orlando Hernández arguably the best Cuban performer in the Big Apple. With his bat and his arm, Céspedes might reverse the trend that has haunted him and become the first Cuban to win the World Series with the Mets.

REYNALDO CRUZ DIAZ is the founder and head editor of the Cuban-based magazine “Universo Béisbol,” which is hosted in MLBlogs. He is a language graduate of the University of Holguin, in his hometown, and has been leading the aforementioned magazine since March 2010. A SABR member since the summer of 2014, he writes, translates, and photographs baseball and was in the first row of the Barack Obama game in Havana, shooting from the Tampa Bay Rays dugout. In spite of the rich history of Cuban baseball, his favorite player happens to be no other than Ichiro Suzuki, whom he hopes to meet and interview. A retro-ballpark lover, he envisions Fenway Park, Wrigley Field, Koshien Stadium, and Estadio Palmar de Junco as the can’t-miss places in baseball.

SOURCES

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author also consulted:

Baseball-encyclopedia

Baseball-Reference.com

NOTES

1 Biography of Sandy Amorós: Rory Costello, edited by Len Levin, Bill Nowlin and Peter C. Bjarkman, Cuban Baseball Legends: Baseball’s Alternative Universe (Society for American Baseball Research, 2016).

2 Idem.

3 Biography of Orlando Hernández and Liván Hernández: Peter C. Bjarkman, edited by Len Levin, Bill Nowlin and Peter C. Bjarkman, Cuban Baseball Legends: Baseball’s Alternative Universe (Society for American Baseball Research, 2016).

4 The very same year in which he broke the single season home run record in Cuba’s National Series, Yoenis Céspedes was completely silenced in the playoffs, which led to his team’s eventual elimination before the finals (Author’s note).