New York’s First Base Ball Club

This article was written by John Thorn

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Big Apple (New York, 2017)

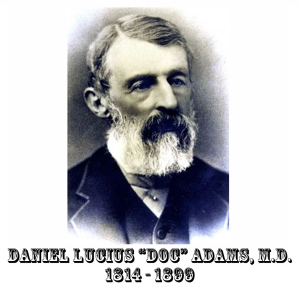

Recent study has revealed the claim of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York to pioneer status, as well as that of Alexander Cartwright to be the game’s inventor, to be suspect if not altogether baseless. I have taken up the latter claim at length in Baseball in the Garden of Eden and will not do so here, except to reiterate my view that baseball was not invented but instead evolved. All the same, however, it had many fathers—prime among them William Rufus Wheaton, Daniel Lucius “Doc” Adams, and Louis F. Wadsworth—each of whom may be credited with specific innovations that were previously credited to Cartwright.1

Adams played ball as early as 1839, the year he came to New York after earning his M.D. at Harvard.2 As he declared to an interviewer in 1896, when he was eighty-one:

Adams played ball as early as 1839, the year he came to New York after earning his M.D. at Harvard.2 As he declared to an interviewer in 1896, when he was eighty-one:

I was always interested in athletics while in college and afterward and soon after going to New York I began to play Base Ball just for exercise, with a number of other young medical men. Before that [i.e., before 1839] there had been a club called the New York Base Ball Club, but it had no very definite organization and did not last long. Some of the younger members of that club got together and formed the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club, September 24, 1845 [actually September 23]…. About a month after the organization of this club, several of us medical fellows joined it, myself among the number.3

Wheaton testified to an interviewer in 1887, when he was seventy-three, that he had written the rules for that New York Base Ball Club in 1837.4 And Wadsworth, who in 1857 gave to baseball the key features of nine innings and nine men to the side, began to play baseball with the Gotham Club, successor to the New Yorks, in 1852 or 1853.5

While the Knickerbocker was the most enduringly influential of the baseball clubs that sprang up prior to the Civil War, it was not the first to play the game, or the first to be organized, or the first to play a “match game” (one contested between two distinct clubs), or the first to play by written rules which we might regard as governing the “New York Game.” This regional variant, in which we may detect the seeds of baseball as we know it today, was distinct from the Massachusetts or New England Game, also called round ball or, with justice, simply “Base Ball,” a descriptive name that applies, in my view, to all games of bat and ball with bases that are run in the round—and thus not only to the New York Game but also to the versions played in Massachusetts, Philadelphia, and elsewhere.

If the Knickerbockers were not the first to play the New York Game, what clubs preceded them? Perhaps it was the Gymnastics and the Sons of Diagoras, clubs associated with Columbia College, who played a game of “Bace” in 1805, which the former won by a score of 41–34.6 Perhaps it was the unnamed clubs that contested at Jones’s Retreat in New York’s Greenwich Village in 1823.7 It may have been the men of the Eagle Ball Club, organized in 1840 to play by rules similar if not identical to those of the KBBC.8 Or it may have been the Magnolia Ball Club or the New York Club, each of which played baseball among themselves at the Elysian Fields of Hoboken in the autumn of 1843 and, like Doc Adams’s medical fellows, had played in New York City before then.

So, it must be said, had many other men who would become Knickerbockers. They were playing ball at Madison Square and Murray Hill in the early 1840s. Charles A. Peverelly, in his Book of American Pastimes (1866), wrote:

At a preliminary meeting, it was suggested that as it was apparent they would soon be driven from Murray Hill, some suitable place should be obtained in New Jersey, where their stay could be permanent; accordingly, a day or two afterwards, enough to make a game assembled at Barclay street ferry, crossed over, marched up the road, prospecting for ground on each side, until they reached the Elysian Fields, where they “settled.” Thus it occurred that a party of gentlemen formed an organization, combining together health, recreation, and social enjoyment, which was the nucleus of the now great American game of Base Ball so popular in all parts of the United States, than which there is none more manly or more health-giving.9

The Knickerbocker party of course did not wander about northern New Jersey looking for a place to play. They had been preceded by other clubs, both baseball and cricket, in selecting the Elysian Fields; proprietor Edwin Augustus Stevens (in conjunction with his brothers) had already donated the use of his grounds to the New York Cricket Club and the New York Yacht Club, and had offered liberal lease terms to the Magnolia and New York baseball clubs.10

In this support of sport, Stevens was of course encouraging traffic to the Elysian Fields: he controlled the ferries as well as the resort, which included the Beacon Course, a horseracing track opened in 1834. By encouraging play (and gambling) on his turf and along his waters, he created a long-standing model for “traction magnates” to own baseball clubs. Of less interest to scholars have been the naming precedents from clubs in sports that captured the public fancy earlier than baseball, but these provide archaeological hints at how baseball developed within pre-established models.

Both the Knickerbocker and New York names were attached to boating clubs in the early years of the century. Rowing was America’s first modern sport, in that competitions were marked by record keeping, prizes, and wagers, yet also provided spectator interest for those with no pecuniary interest. The first boat club to be organized in the United States was named the Knickerbocker, in 1811.11 As reported in the New-York Mirror of July 15, 1837, by boating veteran “Jacob Faithful,” who borrowed his nom de plume from an 1834 novel by Frederick Marryat:

This club suffered a suspension during the war [that of 1812], and for many years subsequently the boat which bore its name was hung up in the New-York Museum, as a model of the finest race-boat ever launched in this port. Subsequent attempts to revive the association fell through; and though many exertions to form new ones were made, yet the first effort that succeeded in establishing the clubs upon their present footing—viz., building their own boats, wearing a regular uniform, and observing rigid navy discipline, was made in the year 1830, by the owners of the barge Sea-drift, a club consisting of one hundred persons, which could boast of one no less distinguished in aquatick and sporting matters than Robert L. Stevens for its first president, with Ogden Hoffman, Charles L. Livingston, Robert Emmet, John Stevens, and other good men and true for his successors. To this club the rudder of the old Knickerbocker was bequeathed, with the archives thereto pertaining: nor was anything spared by the members, during the first years of their existence as a club, to give spirit to its doings.12

Baseball historians take note. Jacob Faithful was attempting to counter a recent assertion in the New York Evening Star that the Wave Club had been the first “to introduce the amusement.” The new organization of 1830 referenced above was named the “New York Boat Club.”13 The Knickerbocker Boat Club—whose very existence had already, by 1837, been cast into oblivion—did not disappear immediately after the War of 1812. It was still conducting boat races and theatrical benefits in 1820. For its celebrated race of November 1820 against the British-born boat builder John Chambers’ American Star, the Knickerbocker Club’s John Baptis built a replacement for his dry-docked Knickerbocker rowboat of 1811 and called it the New York. The New York was characterized in the press as “having the real Knickerbocker [i.e., American] stamp.”14

Boat racing was nothing short of a craze in the 1820s and ’30s, as recalled by Colonel Thomas Picton in Spirit of the Times, July 7, 1883:

After them [the New York and American Star] came the Atalanta, manned by dry-goods clerks; the Seadrift, by bakers; the Neptune, by Fulton Market butchers; the Fairy, by law students; the Columbia and the Halcyon, by city collegians; the Water Witch, by engine runners; the Red Rover, by Ninth Ward firemen, and so on to the end of a miraculous chapter, utterly exhausting the catalogue of sea-gods, nereids and hamadryads deified in pagan mythology. Boat-builders toiled night and day in the production of racing novelties, and one fair of the American Institute, appropriately held at Castle Garden, was almost entirely consecrated to specimens of their art, painted in all the colors of the rainbow, and in others, emanating from overtaxed imaginations, any man inventing a previously-unknown hue being tolerably certain of immediate canonization.

To my eyes, the boating craze, with its attachment of clubs to specific occupations and classes, parallels intriguingly the baseball craze of the 1850s and ’60s.

The New York Cricket Club that has come down in history was organized at McCarty’s Hotel (the Colonnade) in Hoboken on October 11, 1843, as an American-based answer to the St. George Cricket Club, which filled its playing ranks with English nationals. The first twelve members of the NYCC were drawn from the staff of William T. Porter’s Spirit of the Times, with elected members coming from the sporting set that swirled about that weekly journal, including Edward Clark, a lawyer; William Tylee Ranney, a celebrated painter who lived in Hoboken; and James F. Cuppaidge, an accountant who played as “Cuyp the bowler.”15 Some have speculated on a connection between the New York Cricket Club and the New York Base Ball Club, founded in the same year, but firm evidence has not yet emerged. Picton, the NYCC secretary, wrote in the Clipper:

“The New York, with commendable foresight…established their grounds at Hoboken, to the rear of the Elysian Fields. For a couple of years they played upon a section of the domain of Mr. Edwin A. Stevens but subsequently they removed to a more spacious and accessible locality [the Fox Hill Cricket Ground], just beyond the upper end of the old race track [the Beacon, which closed after the 1845 season].”16

The NYCC continued until 1873, but it had stood on the shoulders of earlier cricket clubs bearing the same name. A club of that name had formed in 1837, the same year as the Gotham or New York Base Ball Club, as referenced in the Wheaton reminiscences below. In 1838 it played a match with the Long Island Cricket Club for $500. One year later it played an anniversary match at its grounds on 42nd Street, near the Bloomingdale Road (today’s Broadway). Coexisting with the St. George Cricket Club for a while, ultimately the NYCC merged with it under the latter’s name, a move that inspired Porter to a nationalistic response in 1843.17

According to Chadwick, a “New York Cricket Club” had been founded in 1808 at the Old Shakespeare in Nassau Street; it lasted but one year. But another one predated that by at least six years, meeting at the Bunch of Grapes, at No. 11 Nassau (corner of Cedar and Pine) in 1802.18 A bit of newspaper digging for this essay has revealed an even earlier New York Cricket Club, going back to 1788.19

A New York Sporting Club for the preservation of game within city limits had been created in 1806.20 Members of the Hoboken Turtle Club—New York’s first club, founded at Fraunces Tavern at the corner of Broad and Pearl streets in 1796—were called to order in June 1820 for “Spoon Exercise.” In sum, the notion of a New York Club devoted to baseball did not arise from nothing.

Accordingly, a series of questions confronts us. If baseball was played by organized clubs prior to the Knickerbockers, which of these might lay fair claim to being the true first—that is, first to organize, first to draft rules for play, and first not only to play a match game but also to endure long enough to influence the game’s development? Reflect that the Knickerbockers are credited with playing the first match game, on June 19, 1846…yet history has not accorded an equivalent laurel to their opponents, the New Yorks, who defeated the “pioneers” by a score of 23–1. If the Knicks could not defeat them on the field, however, they were more successful in eradicating them from the historical record, dismissing the victors as unfairly advantaged “cricketers” or, even worse, “disorganized,” a slap at any purposeful aggregation in the rising age of system.

Peverelly offered this capsule portrait of the New York Nine: “It appears that this was not an organized club, but merely a party of gentlemen who played together frequently, and styled themselves the New York Club.”21 Henry Chadwick, who may have fed Peverelly his line, had written in the Beadle Guide in 1860, “We shall not be far wrong if we award to the [Knickerbockers] the honor of being the pioneer of the present game of Base Ball.”22

In fact, the New York Club not only preceded the Knickerbocker in every innovation cited above, but was also its progenitor. The process by which they became two separate clubs may not have been an altogether amicable split. The understanding of veteran baseball players at the turn of the twentieth century was exceedingly hazy as to who had been a Knickerbocker and who a member of the New Yorks. A widely syndicated article by Albert G. Spalding (it appeared in the Akron Beacon Journal on April 1, 1905) announced the formation of an investigative body to examine the origins of baseball; this has come to be known as the Mills Commission. (This article was read by Abner Graves, who responded to the editor of the newspaper and lifted Abner Doubleday to inventor status.) Extracting from the materials he had received from Chadwick, Spalding named eleven men as Knickerbocker Base Ball Club founders, including: “Colonel James Lee, Dr. Ransom, Abraham Tucker, James Fisher, W. Vail, Alexander J. Cartwright, William R. Wheaton, Duncan F. Curry, E. R. Dupignac Jr., William H. Tucker, and Daniel L. Adams.” The first four of these played with the New York or Gotham club, as did Wheaton and Tucker. The last named, Adams, did not join the Knickerbocker until one month after its founding.

Known as the New York or Gotham or Washington from the 1830s through the 1860s, these clubs were lineally the same, and appear to have gone by several names at the same time. The murky relationship between the original Gothams of 1837, the Washingtons, the New Yorks, the Knickerbockers, and the later Gothams may be summarized below.

Because they regarded themselves as the first organized club, the Gotham Club was also called the Washington. A matter of custom, this practice was said to denote that they were, like the father of our country, first. Another explanation, personally alluring but not yet proven, is that the Gotham’s alternative name referred to its origins with the influential merchant class—mostly butchers and produce brokers—of Washington Market, founded in 1812. Some of these men organized in 1818 as New York City’s first target company (for archery and riflery), which they named the Washington Market Chowder Club.23 It survived all the way through the Mexican War into the next decade. The Tribune reported on November 29, 1850:

Washington Market Chowder Club. A company bearing the above name, composed, we understand of the butchers of Washington Market, passed our office yesterday morning on a target excursion, accompanied by Dodsworth’s Band. They were very numerous, and fine looking body of men. And it would be indeed surprising that any company composed of butchers should be anything else than fine looking; that occupation embraces the most robust and hardy men in the city.

Many in the meat trade went on to become political wheeler-dealers and sporting men (not sportsmen), from Bill “the Butcher” Poole—whose father had been a Washington Market butcher before him, with his stand occupying the same place—to James McCloud, the butcher and pool-seller who facilitated the Louisville game-fixing scandal of 1877.

St. George Cricket Club at Hoboken, New Jersey, 1861. Note the child prodigy George Wright, standing at center.

The weekly New York Illustrated offered a colorful capsule of the Washington Market in 1870:

Flour, meal, butter, eggs, cheese, meats, poultry, fish, cram the tall warehouses and rude sheds, teeming at the water’s edge, to their fullest capacity. Fruit-famed, vegetable-renowned Jersey pours four-fifths of its products into this lap of distributive commerce; the river-hugging counties above contribute their share, and car-loads come trundling in from the West to feed this perpetually hungry maw of the Empire City. The concentration of this great and stirring trade is to be met with at Washington Market. This vast wooden structure, with its numerous out-buildings and sheds, is an irregular and unsightly one, but presents a most novel and interesting scene within and without. The sheds are mainly devoted to smaller stands and smaller sales. Women with baskets of fish and tubs of tripe on their heads, lusty butcher-boys lugging halves and quarters of beef or mutton into their carts, pedlars of every description, etc., tend to amuse and bewilder at the same time. Some of the produce dealers and brokers, who occupy the little box-like shanties facing the market from the river, do a business almost as large as any of the neighboring merchants boasting their five-story warehouses.24

This Gotham Base Ball Club pin, the only example known, belonged to Henry Mortimer Platt, who had played a single match game with the club in 1854. The three men in a tub refers to an ancient Mother Goose rhyme: “Three wise men of Gotham went to sea in a bowl,” it went; “if the bowl had been stronger, then my rhyme had been longer.”

At some point in the early 1840s the Gotham club was renamed the New York Ball Club, retaining most if not all of its Gotham members. The New Yorks then spun off the Knickerbockers, as Wheaton relates in the 1887 interview offered verbatim below. The Gotham, meanwhile, continued to play ball among themselves from 1845 to 1849, just as the Knickerbocker and Eagle clubs appear to have done. In 1850 those Gotham and New York members who had not attached to the Knickerbockers in Hoboken reconstituted themselves as, yet again, the Washingtons, playing at the Red House Grounds (“a most comfortable ‘asylum for distressed husbands,’” offered Spirit of the Times) at Second Avenue and 105th Street in New York.

In 1851 this Washington Base Ball Club challenged the Knickerbockers to match games that have been preserved in the historical record. In 1852 the club reverted to its old name of Gothams, “consolidating with” the Washingtons.25

Admittedly, this is a serpentine path. Let me now bring in William Rufus Wheaton to help fill in the story. Born in 1814, Wheaton attended New York’s Union Hall Academy, at the corner of Prince and Oliver streets, near Chatham Square and the racket court and handball alley at Allen Street, which he appears to have frequented. He read law with the notable attorney John Leveridge, passed the bar in 1836, was active in the New York 7th Regiment, and in 1841 was admitted to practice in the Court of Chancery and the Supreme Court of New York. His legal training, more than that of any other original Knick mentioned as a “father of baseball,” equipped him to codify the venerable if still anecdotal playing rules.

Admittedly, this is a serpentine path. Let me now bring in William Rufus Wheaton to help fill in the story. Born in 1814, Wheaton attended New York’s Union Hall Academy, at the corner of Prince and Oliver streets, near Chatham Square and the racket court and handball alley at Allen Street, which he appears to have frequented. He read law with the notable attorney John Leveridge, passed the bar in 1836, was active in the New York 7th Regiment, and in 1841 was admitted to practice in the Court of Chancery and the Supreme Court of New York. His legal training, more than that of any other original Knick mentioned as a “father of baseball,” equipped him to codify the venerable if still anecdotal playing rules.

Wheaton was a solid cricketer as well as a baseballist. He umpired two baseball games played between the New York and Brooklyn clubs on October 21 and 24, 1845, both of which were played eight to the side and reported in the press, with accompanying box scores. He recruited members for the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club, as Peverelly noted. He was the club’s first vice president. Although paired with the tobacconist William H. Tucker as the entirety of the Knickerbocker Committee on By-Laws, Wheaton appears to have been the one who truly wrote the rules that were formalized on September 23, 1845. Before that, by his own account, he drew up the rules for the Gotham club of the 1830s, which the Knickerbockers adopted with little change aside from repealing the Gotham provision for an out to be recorded by a catch on the fly.

By the spring of 1846, however, barely six months after the founding of the Knickerbocker Club, Wheaton resigned. We do not know the circumstances. On June 5 of that year, the Knickerbockers, not yet one year old, elected their first honorary members, forty-nine-year-old James Lee and fifty-three-year-old Abraham Tucker, both of whom had been Gothams. Wheaton was not accorded such an honor.26 He left the Knickerbockers and returned to active play at cricket, going on to win a trophy bat for highest score in a match of the New York Cricket Club in October 1848.27

On January 28, 1849, a month before Alexander Cartwright’s departure from New York, Wheaton embarked for California in a speculative venture called the New York Mining Company, in which he was one of a hundred gold-besotted souls who purchased and outfitted a ship, the Strafford, for what would be a 213-day journey to San Francisco around Cape Horn. Although he returned east upon occasion, he made his substantial business and political career in the West.

On Sunday, November 27, 1887, an “interesting history” appeared on page fourteen of the San Francisco Examiner. It was entitled “How Baseball Began—a Member of the Gotham Club of Fifty Years Ago Tells About It.” This interview with an unnamed “old pioneer,” undoubtedly Wheaton, lay buried in the microfilm archives until 2004, when Randall Brown published extensive excerpts from it in his landmark article, “How Baseball Began,” in SABR’s National Pastime.28 Here is the entirety of the Examiner piece, with variant spellings and styles intact:

HOW BASEBALL BEGAN

A Member of the Gotham Club of Fifty Years Ago Tells About It.

PLAYED FOR FUN THEN.

The Game Was the Outgrowth of Three-Cornered Cat, Which

Had Become Too Tame.

Baseball to-day is not by any means the game from which it sprang. Old men can recollect the time when the only characteristic American ball sport was three-cornered cat, played with a yarn ball and flat paddles.

The game had an humble beginning. An old pioneer, formerly a well-known lawyer and politician, now living in Oakland, related the following interesting history of how it originated to an EXAMINER reporter:

“In the thirties I lived at the corner of Rutgers street and East Broadway in New York. I was admitted to the bar in ’36, and was very fond of physical exercise. In fact we all were in those days, and we sought it wherever it could be found. There were at that time two cricket clubs in New York city, the St. George and the New York, and one in Brooklyn called the ‘Star,’ of which Alexander Campbell, who afterwards became well known as a criminal lawyer in ‘Frisco, was a member. There was a racket club in Allen street with an inclosed court. [A note in the Clipper on October 23, 1880, evokes the period: “In olden times Chatham square used to be an open meadow or common, and was the play-ground of the boys of this city. Baseball was the favorite game played on the square, but it was then a simple pastime, with flat sticks or axe-handles for bats, and yarn balls. Occasionally a boy, more lucky than the rest, would bring on the ground a ball made of a sturgeon’s nose, procured from the racket court in Allen street, where it had been driven over the wall by a rash blow.”]

[“]Myself and intimates, young merchants, lawyers and physicians, found cricket to[o] slow and lazy a game. We couldn’t get enough exercise out of it. Only the bowler and the batter had anything to do, and the rest of the players might stand around all the afternoon without getting a chance to stretch their legs. Racket was lively enough, but it was expensive and not in an open field where we could have full swing and plenty of fresh air with a chance to roll on the grass. Three-cornered cat was a boy’s game, and did well enough for slight youngsters, but it was a dangerous game for powerful men, because the ball was thrown to put out a man between bases, and it had to hit the runner to put him out. The ball was made of a hard rubber center, tightly wrapped with yarn, and in the hands of a strong-armed man it was a terrible missile, and sometimes had fatal results when it came in contact with a delicate part of the player’s anatomy.”

THE GOTHAM BASEBALL CLUB.

“We had to have a good outdoor game, and as the games then in vogue didn’t suit us we decided to remodel three-cornered cat and make a new game. We first organized what we called the Gotham Baseball Club. This was the first ball organization in the United States, and it was completed in 1837. Among the members were Dr. John Miller, a popular physician of that day; John Murphy, a well-known hotel-keeper; and James Lee, President of the New York Chamber of Commerce. To show the difference between times then and now, it is enough to say that you would as soon expect to find a Bishop or Chief Justice playing ball as the present President of the Chamber of Commerce. Yet in old times everybody was fond of outdoor exercise, and sober merchants and practitioners played ball till their joints got so stiff with age they couldn’t run. It is to the oft-repeated and vigorous open-air exercise of my early manhood that I owe my vigor at the age of 73.

“The first step we took in making baseball was to abolish the rule of throwing the ball at the runner and order that it should be thrown to the baseman instead, who had to touch the runner with it before he reached the base. During the regime of three-cornered cat there were no regular bases, but only such permanent objects as a bedded boulder or an old stump, and often the diamond looked strangely like an irregular polygon. We laid out the ground at Madison square in the form of an accurate diamond, with home-plate and sand-bags for bases. You must remember that what is now called Madison square, opposite the Fifth Avenue Hotel, in the thirties was out in the country, far from the city limits. We had no short-stop, and often played with only six or seven men on a side. The scorer kept the game in a book we had made for that purpose, and it was he who decided all disputed points. The modern umpire and his tribulations were unknown to us.”

HOW THEY PLAYED THEN.

“We played for fun and health, and won every time. The pitcher really pitched the ball and underhand throwing was forbidden. Moreover he pitched the ball so the batsman could strike it and give some work to the fielders. The men outside the diamond always placed themselves where they could do the most good and take part in the game. Nowadays the game seems to be played almost entirely by the pitcher and catcher. The pitcher sends his ball purposely in a baffling way, so that the batsman half the time can’t get a strike [meaning “a hit”] or reach a base. After the Gotham club had been in existence a few months it was found necessary to reduce the rules of the new game to writing. This work fell to my hands, and the code I then formulated is substantially that in use to-day. We abandoned the old rule of putting out on the first bound and confined it to fly catching. The Gothams played a game of ball with the Star Cricket Club of Brooklyn and beat the Englishmen out of sight, of course. That game and the return were the only two matches [i.e., games with other clubs] ever played by the first baseball club. [NOTE: These undoubtedly refer to the contests of October 1845.]

“The new game quickly became very popular with New Yorkers, and the numbers of the club soon swelled beyond the fastidious notions of some of us, and we decided to withdraw and found a new organization, which we called the Knickerbocker. For a playground we chose the Elysian fields of Hoboken, just across the Hudson river. And those fields were truly Elysian to us in those days. There was a broad, firm, greensward, fringed with fine shady trees, where we could recline during intervals, when waiting for a strike [i.e., a turn at bat], and take a refreshing rest.”

LOTS OF EXERCISE AND FUN.

“We played no exhibition or match games, but often our families would come over and look on with much enjoyment. Then we used to have dinner in the middle of the day, and twice a week we would spend the whole afternoon in ball play. We were all mature men and in business, but we didn’t have too much of it as they do nowadays. There was none of that hurry and worry so characteristic of the present New York. We enjoyed life and didn’t wear out so fast. In the old game when a man struck out[,] those of his side who happened to be on the bases had to come in and lose that chance of making a run. We changed that and made the rule which holds good now. The difference between cricket and baseball illustrates the difference between our lively people and the phlegmatic English. Before the new game was made we all played cricket, and I was so proficient as to win the prize bat and ball with a score of 60 in a match cricket game in New York of 1848, the year before I came to this Coast. But I never liked cricket as well as our game. When I saw the game between the Unions and the Bohemians the other day, I said to myself if some of my old playmates who have been dead forty years could arise and see this game they would declare it was the same old game we used to play in the Elysian Fields, with the exception of the short-stop, the umpire, and such slight variations as the swift underhand throw, the masked catcher and the uniforms of the players. We started out to make a game simply for safe and healthy recreation. Now, it seems, baseball is played for money and has become a regular business, and, doubtless, the hope of beholding a head or limb broken is no small part of the attraction to many onlookers.”

***

The scorebook that Wheaton referenced, along with the Gotham by-laws and playing rules, was not a figment of his aged imagination. Gotham shortstop Charles C. Commerford wrote to Henry Chadwick in 1905 that the first baseball game he saw (he played in the 1840s and 1850s) was played by the New York Club, which “had its grounds on a field bounded by 23rd and 24th streets and 5th and 6th avenues.” Commerford would have seen this game just prior to the fall of 1843, when the New York Ball Club moved its playing grounds to Hoboken. “There was a roadside resort nearby [the Madison Cottage] and a trotting track in the locality. I remember very well that the constitution and by-laws of the old Gotham club, of which I became a member in 1849, stated that the Gotham Club was the successor of the old New York City Club.”29

Commerford added, in a 1911 letter to the New York World: “There was always some little contention between the Knickerbocker Club and the Gotham Club as to the date of organization. The Knickerbockers claimed that they were the first to organize and the Gothams claimed priority, as the New York Club was merged into the Gotham and the former (New York) always insisted that they were the first to organize as such.”30

To provide additional gloss on Wheaton’s reminiscence, the games cited above, in which the Gothams “beat the Englishmen out of sight,” were the very same games recorded in the press as pitting New York against Brooklyn in late October 1845. These were the last two of three games played between representatives of the two cities in that month, although we cannot say for certain that the first game was played by the same clubs as the latter two, as no box score survives to identify its contestants.

The Knickerbockers played their first recorded game, an intrasquad contest, in that month as well. On October 6, seven Knicks won by a count of 11–8 over seven of their fellows in three innings. Wheaton was the umpire. William H. Tucker scored three of the losing squad’s eight runs.31 Like Wheaton and other Knickerbockers, he had been a player with the New York Base Ball Club and maintained his tie to them, indeed playing in the two formal matches of the New Yorks with the Brooklyn Club on October 21 and 24 of 1845, a month after he had helped to form the Knicks. In The Tented Field: A History of Cricket in America, author Tom Melville pointed to an even earlier contest between Brooklyn and New York clubs, played on October 10 and reported in the New York Morning News.32 Research more than a decade later has revealed a somewhat fuller account in the obscure and short-lived newspaper the True Sun:

The Base Ball match between eight Brooklyn players, and eight players of New York, came off on Friday on the grounds of the Union Star Cricket Club. The Yorkers were singularly unfortunate in scoring but one run in their three innings. Brooklyn scored 22 and of course came off winners.33

Many of the early New York baseballists had cut their teeth on cricket, and this was true of the Brooklyn players as well. In the game of October 21, conducted at the Elysian Fields, the eight players of the New York club won handily. They did so again in the game three days later, played at the grounds of the Union Star Cricket Club, opposite Sharp’s Hotel, at the corner of Myrtle and Portland Avenues near Fort Greene. The scores were, respectively, 24–4 and 37–19. On both these occasions the Brooklyn baseballists included established cricketers John Hines, William Gilmore, John Hardy, William H. Sharp, and Theodore Forman.34 Their lineup appears to have been identical for the two games, as the Ayers in the October 21 box score and the Meyers of October 24 may be alternative renderings of the same individual. The other seven Brooklynites match up.

For me, the New York Base Ball Club second anniversary game of November 10, 1845, reported in the New York Herald on the following day, has much in common with the purported “first match game” of June 19, 1846, while the games of October 1845, particularly the latter two, seem to be true match games between wholly differentiated clubs. It could be argued—I certainly would—that the Knickerbockers played no match games until they met the Washington club on June 3, 1851, a game the Knicks won by a count of 21–11. Look at the cast of characters in the Herald’s account of the anniversary game.

NEW YORK BASE BALL CLUB: The second Anniversary of this Club came off yesterday, on the ground in the Elysian fields. The game was as follows:

| Runs | Runs | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Murphy | 4 | Winslow | 4 |

| Johnson | 4 | Case | 4 |

| Lyon | 3 | Granger | 1 |

| Wheaton | 3 | Lalor | 3 |

| Sweet | 3 | Cone | 1 |

| Seaman | 1 | Sweet | 4 |

| Venn | 2 | Harold | 3 |

| Gilmore | 1 | Clair | 2 |

| Tucker | 3 | Wilson | 1 |

| 24 | 23 |

J.M. Marsh, Esq., Umpire and Scorer

After the match, the parties took dinner at Mr. McCarty’s, Hoboken, as a wind up for the season. The Club were honored by the presence of representatives from the Union Star Cricket Club, the Knickerbocker Clubs, senior and junior, and other gentlemen of note.35

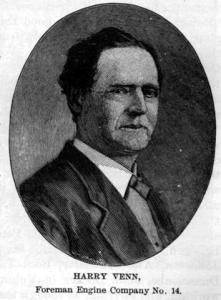

Several interesting things emerge from this notice of the game. Prominent Knickerbocker names are present—Wheaton, Tucker, Cone, Clair (Clare). So too are Gotham players of prominence—Lalor, Murphy, Johnson, Winslow, Case. The Davis who plays here and in the game of June 19, 1846, is not the Knickerbocker James Whyte Davis, who played opposite him in at least one contest after J. W. Davis’s entrance on the scene in 1850. Venn is Harry Venn, celebrated Bowery icon and proprietor of the Gotham Cottage (a billiard and bowling saloon) at 298 Bowery, longtime clubhouse to the Gotham BBC. Gilmore may well be the Union Star cricketer who played baseball with the Brooklyns on October 21 and 24.

The game of November 10 was played nine to the side, clearly to 21 runs or more in equal innings, a rule that may have been invoked only for formalized contests. The two sides were unnamed. While the New Yorks were celebrating their second year as an organized club, on another field in Hoboken that very same day, the Knickerbockers were playing an intramural match all their own, eight to the side.

So who were these mysterious NYBBC players, so important to baseball’s development yet nearly invisible in the shadow of the Knickerbocker Club? Let me supply a brief record with identifications for a few major figures. An addendum to this essay will portray, in a more perfunctory manner than it deserves, the reconstituted Gotham Club from 1852 until it drifted into inconsequence after the professionals formed their league in 1871. Someone ought to write a book.

***

According to Peverelly, the Gotham Base Ball Club of New York was organized early in 1852, with a mysterious Mr. Tuche as its first president. In his Book of American Pastimes he treated the Washington Base Ball Club as a separate entity, supplying slim details of their two matches with the Knickerbockers on June 3 and 17, 1851. For the first, which the Knicks won by a count of 21–11 in eight innings at the Red House Grounds, all that he had was a line score (both games went unreported in the press). For the second game, which the Knicks won 22–20 in ten innings, he listed the Washington players, several of whom we recognize as New York Base Ball Club players from the 1845 anniversary game and the purported match game of June 19, 1846: William. H. Van Cott, Trenchard, Barnes, William Burns, C[harles] Davis, Robert Winslow, Charles L. Case, Jackson, Thomas Van Cott. Peverelly also lists the officers of the Gotham Club since 1856 and describes the club uniform of ten years after as “a blue merino cap, with a white star in the centre; white flannel shirt, with red cord binding; blue flannel pants, red belt, and white buckskin shoes.”

This Gotham Base Ball Club pin, the only example known, belonged to Henry Mortimer Platt, who had played a single match game with the club in 1854. The three men in a tub refers to an ancient Mother Goose rhyme: “Three wise men of Gotham went to sea in a bowl,” it went; “if the bowl had been stronger, then my rhyme had been longer.”

When the Gothams met the Knicks on July 1, 1853, a game interrupted by rain and resumed on the 5th, their players included: (William) Vail, W. H. Van Cott, Thomas Van Cott, (Robert) Winslow Sr., (Robert) Winslow Jr., Jonathan (John) Lalor, Reuben H. Cudlipp, and two highly skilled new players—Joseph C. Pinckney and Louis F. Wadsworth, both of whom would soon leave the club for greener pastures, perhaps lured by emoluments. Another Gotham with a vagabond temperament was second baseman Edward G. Saltzman, who in the spring of 1856 relocated his jewelry trade to Boston. With Brooklynites Augustus P. Margot and Richard Busteed, Saltzman organized the Tri-Mountain Club to play baseball by New York rules.

On November 7, 1857, correspondent “X” wrote of that year’s edition of the club in Porter’s Spirit of the Times:

Their best men are: Messrs. Vail, Van Cott, Cudlipp, [William] Johnson, [John] McCosker, Wadsworth, Sheriden [Phil Sheridan], Turner, and [Charles] Commerford. Mr. Vail, one of the oldest players in this city, and one of the original members, has had great experience; he has filled the position of catcher since Mr. Burns left (the club miss this player very much). He is a strong bat, and plays with good judgment. Mr. Van Cott stands very high as pitcher, combining speed with an even ball. Mr. Wadsworth formerly belonged to the Knickerbocker [which he joined in 1854, coming from the Gotham], and until the last year or so played in all their matches, but left them through some misunderstanding. It is claimed by his friends that he is the best first base man in any club, perfectly fearless—he will stop any ball that may come within reach—is a good player in any position, as his fielding last Friday will show. McCosker and Johnson are both fine catchers, and remarkably strong batsmen; and of the others it may be said, that if not powerful batters, they are what is termed sure ones, and good catchers…. The Gotham formerly played on the grounds of the Red House, and would probably have played there to this day, had there not some difficulty sprung up with the proprietor or lessee. They play at Hoboken, on grounds but slightly inferior to their old locality.36

The Old Gotham Inn and Bowling Saloon, at 298 Bowery, as depicted in 1862.

The Gothams believed they were direct descendants from not only the Washington Club (which they averred to have organized in 1849, not 1850 as Peverelly had it), but also from the primal New York Club. The club limped along through the 1870s as the professionals took hold of the game. In 1871, following the formation of the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, first professional organization, the Gothams joined with thirty-two other clubs, including the venerable Knickerbocker and Eagle clubs, hoping to keep top-level amateur play alive. In a last-gasp member-recruitment circular issued at the opening of the centennial year of 1876, the club’s directors wrote, “The Gotham Base Ball Club dates its existence from the year 1849; it is, therefore, one of the oldest—if not the oldest—organization of its kind in the country.”37

A few weeks later, The New York Times reported on the meeting of old Gotham players that resulted. It was noted that this club had “turned out more professional players than any other,” which oddly may have been true. Buried in the notice was the still, to this day, not fully fathomed heritage of the club—like that of the game itself—in the rough and rowdy crowd that populated Washington Market long before.

The meeting on Monday evening was a large and very harmonious one. Old times were talked over, and a unanimous feeling prevailed in favor of reorganizing and keeping up the old club. Mr. James B. Mingay, a gentleman who has done business in Jefferson Market for over thirty years past, was elected president and Mr. Abraham H. Hummel, of the law firm of Howe & Hummel, at No. 89 Centre street, was made Vice President. [Hummel was the notorious underworld lawyer of his day.] The Secretary is Mr. Melchior B. Mason of No. 32 Chambers Street and the treasurer, Mr. Leonard Cohen, of Washington Market. There were about forty of the old members present; and among those who will take an active part in the new organization are Mr. Seaman Lichtenstein, of No. 83 Barclay street, who has been in business over thirty-five years…Mr. John Drohan, Mr. James Forsyth, and Mr. Richard H. Thorn, all merchants of Washington Market, of between twenty and thirty years’ standing.38

PLAYER PROFILES

Cornelius V. Anderson: President of the Washington Club in the early 1850s after being the Chief Engineer of the Volunteer Firemen from 1837 to 1848. His portrait was prominently displayed at Harry Venn’s Gotham Cottage at 298 Bowery, the ball club’s headquarters after 1845. Born in New York City on April 1, 1809, Anderson was a mason by trade. In 1852 he became the first president of the Lorillard Fire Insurance Company. His health began to fail in 1856 and he died on November 22, 1858. He was revered among the city’s firemen, who erected an elaborate tombstone in his honor at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery.

Charles H. Beadle: First baseman and officer of the Gotham Club during and after the Civil War, into the 1870s. Charles’s brother, Edward Beadle, was also involved in the club and both brothers later moved to Cranford, New Jersey, where Edward served as mayor in 1885.

Edward Bonnell: Edward Bonnell was recalled by George Zettlein as “one of the players” on the Gothams. Born around 1825, Bonnell was a liquor dealer before becoming a member of the New York Board of Fire Commissioners in 1865. Zettlein reported that Bonnell was living in Philadelphia in 1887.39

William F. Burns: A Gotham catcher in 1855–56. According to the Clipper article quoted in the profile of Venn, Burns died in the 1857 sinking of the SS Central America. Contemporary coverage of that tragedy does indeed list among the missing: “William Burns of New York City. Had been in California about a year.”40

C[larence] A. Burtis: The leading Gotham player of 1860, in which his runs per game ratio was the third best in the National Association, behind only Grum of the Eckfords and Leggett of the Excelsiors. In a game against the Mutuals on September 4, 1860, Burtis hit two home runs. After playing for the Gotham Club in 1859 and 1860, Burtis was absent from the lineup in 1861. He was back by the summer of 1862 and played through at least 1865. He also played in an 1888 old-timer’s benefit game for John Zeller, crippled by a gruesome baseball injury. George Zettlein described Burtis [though recalling him as Bustis] as a “boss painter in the Ninth ward,” so he can only be Clarence A. Burtis, a painter who was born around 1835 and died in Manhattan on May 16, 1894. Burtis enlisted in the New York Infantry, Regiment 83, on May 26, 1861, and was a Sergeant-Major by the time of his discharge in June of 1862. Like many of his fellow club members, Burtis was also very active in the fire department.

Charles Ludlow Case: Born in Newburgh, New York, in 1818, he was a NYBBC player in the contest of November 10, 1845, when he resided at 7 Murray and was a merchant at 101 Front. He was at one time a butcher at Washington Market. He also played for the New York Club in the two games against the cricketers from the Union Star of Brooklyn on October 21 and 24, 1845. In the game of June 19, 1846, he played with the club designated as the New Yorks. Case arrived in San Francisco for the Gold Rush on February 27, 1849. At a meeting of January 6, 1851, he became a member of the Finance Committee of the newly formed Knickerbocker Association, composed of New York residents living in San Francisco. He was joined on that committee by Edward A. Ebbets and Frank Turk, who had been members of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York. It is reasonable to think that they were among the unnamed men reported to have played baseball in Portsmouth Square in 1851.41 Case returned east and died in Newburgh on March 25, 1857.

Leonard G. Cohen: Officer of the Gotham Club during and after the Civil War; catcher for the ball club. As of 1869 he was a fruit dealer in Washington Market and living at 144 West Street. Cohen was born around 1839 in New York to a Polish-born father (though one census had Germany). He later moved to Westfield, New Jersey, where he served as the first postmaster and was still living as late as 1910.

Charles C. Commerford: Born in New York City, June 2, 1833; died in Waterbury, Connecticut, February 6, 1920. Played shortstop with Gothams and later the Eagles. Moved from New York to Waterbury, Connecticut, in 1864, where he continued to play ball. After some political successes, he was appointed postmaster there by President Grover Cleveland in 1886. His father, the chair-maker John Commerford of New York City, was an abolitionist prominently identified with labor interests, and was a candidate for Congress on the Republican ticket in 1860.

Charles C. Commerford: Born in New York City, June 2, 1833; died in Waterbury, Connecticut, February 6, 1920. Played shortstop with Gothams and later the Eagles. Moved from New York to Waterbury, Connecticut, in 1864, where he continued to play ball. After some political successes, he was appointed postmaster there by President Grover Cleveland in 1886. His father, the chair-maker John Commerford of New York City, was an abolitionist prominently identified with labor interests, and was a candidate for Congress on the Republican ticket in 1860.

John Connell: George Zettlein described this man as a member of the Gothams and added that he “was on the Herald for some time, and is still [in 1887] a writer.”

Reuben Henry Cudlipp: Reuben Cudlipp was a Nassau Street lawyer who served as vice president of the Gotham Club in 1856 and as one of the vice presidents of the NABBP in 1857. He also played for the first nine until 1858. One of the Gothams’ better players, he was proposed for membership in the Knickerbockers on April 1, 1854, the same date as that of Louis F. Wadsworth’s similar move.42 Still active as a New York attorney in 1894, he resided at that time in Plainfield, New Jersey, as did Wadsworth (as shown in the NYC Directory for 1894, via ancestry.com). Cudlipp was seventy-eight when he died at his daughter’s home in Yonkers on December 5, 1899.

C[harles?] Davis: A frequent entrant in the NYBBC box scores, he has been mistaken in print for the celebrated Knickerbocker James Whyte Davis, against whom he played.

William W. De Milt: Like Harry Venn and Seaman Lichtenstein, he was a member of the Columbian Engine Company, No 14. As a carpenter and machinist for the Union Square, Brougham’s Lyceum (where fellow Gotham George W. Smith worked in 1850) and other New York theatres, he was responsible for producing a wide variety of stage apparatus and special effects. Born 1814, died 1875. Buried at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery.

Patsy Dockney: Born in Ireland ca. 1844, he was a catcher with Gotham in 1864–65. Paid under the table to move to Athletics of Philadelphia in 1866, according to the Philadelphia Times, Dockney “used to play ball every afternoon and fight and drink every night. He was a tough of the toughs.”

Andrew J. Dupignac: Andrew Dupignac, Gotham Club secretary in 1860 and 1861, was born around 1828. He later became the president of the New York Skating Club and in 1903 was described as “the oldest living amateur skater.”43 Dupignac died in Brooklyn on November 27, 1908.

James Fisher: Identity not known for certain but after thorough review of the New York City directories and considering other factors, I tentatively conclude that this early player, according to Peverelly, was James H. Fisher. Roughly the same age as the two other prominent players who were named honorary Knickerbockers in June 1846—Col. James Lee and Abraham Tucker (the former born in 1796, the latter in 1793)—Fisher was born in 1798. Like Lee, he had made his fortune by 1850 and in the census lists his occupation as “gentleman.” Previously he had listed his profession, with subtlety, as “agent.” In 1847, the year of his death, his address was 134 Allen Street, the neighborhood from which Wheaton and his mates had begun their search for lively recreation.

Robert Forsyth: In 1855, the year after the death of the affluent patron of this independent military company, the Herald reported: The Forsyth Cadets, a well drilled company, composed chiefly of butchers belonging to Washington Market, will make their annual parade on the 18th inst.”44 Shortly before his death, the Clipper observed: “This organization is named in honor of Robert Forsyth, Esq., a gentleman whose name is a “Household Word” to all those who have occasion to visit Washington Market, being one of the most extensive dealers connected with that place. He must indeed feel honored at the compliment paid him by the ‘Cadets.’”45 Robert Forsyth’s sons, Joseph and James, were both Gotham Club members. According to the 1887 New York Sun article, Joseph was already dead while James was an oyster dealer.

George H. Franklin: George H. Franklin was one of the club’s representatives at the 1857 NABBP convention.

Andrew Gibney: Starting with Gotham Juniors in 1863, he graduated to senior club the following year and played second base with the Gothams in 1865, then center field with the Nationals of Washington in 1866. He played professionally with Olympics of Washington in 1870. Alfred W. “Count” Gedney played as Gibney with the Keystone club in Philadelphia in his early years, but these two are not the same individual.

John V(an) B(uskirk) Hatfield: Widely regarded as one of the best players of the 1860s, with the Eckford and Mutual clubs, he also played one year with the Gothams, in 1865.

Johnson: Played in the NYBBC anniversary contest of November 10, 1845. Harold Peterson, in his book The Man Who Invented Baseball, names him as a Knickerbocker and calls him F. C. Johnson. However, Francis Upton Johnston was a member of the Knickerbocker and the New-York Academy of Medicine., as were D. L. Adams and Franklin Ransom. One of his sons also practiced medicine for many years at Hyde Park, where he is buried. The NYBBC Johnson may, however, be neither man but instead William Johnson, named in a reminiscence of the Gotham Cottage by Colonel Thomas Picton in 1878, and a player for the club in the 1850s.

John Lalor: This sturdy New York and Gotham player is surely the Jonathan Lalor listed in the box score published in Spirit in the Times on July 9, 1853, detailing a match game between the Knicks and Gothams. He also played in the NYBBC second anniversary game of November 10, 1845. Harold Peterson, in his book The Man Who Invented Baseball, instead identifies the player as Michael Lalor, “Segar Seller.” I think it is constable John Lalor, who umpired the Knickerbocker intramural game of June 26, 1846 and signed his name in full this way. This fellow was an up-and-comer in the Whig party in the Fifteenth Ward in 1845, and later its leader in the Seventh Ward. A lawyer by profession, he served in the Civil War, organizing the 15th Regiment, known as McLeod Murphy’s Engineers. John Lalor was born in 1819 and died on February 21, 1884. His obituary in the Herald noted that he was “a member of the Gotham club.” At his death he was chief clerk at Castle Garden.

Col. James Lee: According to Wheaton, he was one of the original Gotham Club members of 1837. Born December 3, 1796, he was a prominent businessman and sportsman. President of the New York Chamber of Commerce, he claimed to have played baseball in New York City ca. 1800.

John Ward wrote, in How to Become a Base-Ball Player (1888),

Colonel Jas. Lee, elected an honorary member of the Knickerbocker Club in 1846, said that he had often played the same game when a boy, and at that time he was a man of sixty or more years. [In fact he was fifty.] Mr. Wm. F. Ladd, my informant, one of the original members of the Knickerbockers, says that he never in any way doubted Colonel Lee’s declaration, because he was a gentleman eminently worthy of belief.

In 1907 Ward added to his remarks about Lee a sentence that echoes editor Porter’s reason for establishing the New York Cricket Club:

Another interesting tale told me by Mr. Ladd was that the reason they chose the game of Base Ball instead of—and in fact in opposition to—cricket was because they regarded Base Ball as a purely American game; and it appears that there was at that time some considerable prejudice against adopting any game of foreign invention.46

Lee died June 16, 1874.

Seaman Lichtenstein: A candidate for the first Jewish player, Lichtenstein began to run with Columbian Engine No. 14 at the age of fifteen, becoming a member of the company in 1849, at age twenty-four. He began his business career salvaging scraps from the butchers at Washington Market, selling the meat to the Native Americans who lived in Hoboken and the bones to a manufacturer of glue (Peter Cooper). In the 1880s, he owned a trotter named for Gotham Cottage proprietor and archetypal Bowery B’hoy Harry Venn. He died at age seventy-seven on December 24, 1902.47

John McCosker: A third baseman, he began play with the Gothams in 1856 and played in Fashion Race Course Game 3 and in many games for the Gothams of the 1850s. Tom Shieber reported in the 1997 National Pastime: “In a match game played between the Gotham and Empire clubs in September of 1857, McCosker hit a home run with the bases full. While he was most probably not the first to accomplish the feat, the description in the New York Clipper is the earliest known recounting of what would later be termed a grand slam: ‘The Gothamites…scored 4 beautifully in their last innings, chiefly owing to a tremendous ground strike by Mr. McCosker, bringing each man home as well as himself.’”

George Zettlein described McCosker (“McClosky”) as an engineer of the Fire Department, so there can be no question that the ballplayer was John A. McCosker, who was born around 1829 and was a fire department engineer prior to the war. When the war started, McCosker was one of the organizers of the 73rd Infantry—the Second Fire Zouaves—in which he served as a quartermaster until being discharged on August 4, 1862. His whereabouts become much harder to trace after that, but he may have died in 1881.

Dr. John Miller: According to Wheaton, he was one of the original Gotham BBC members of 1837. In 1842 John Miller, physician, is at 74 James Street. In 1845 he is at 186 East Broadway.

James B. Mingay: Mingay entered the poultry business in Jefferson Market in his youth and remained in it until age seventy-two. For 14 years he was a member of the Volunteer Fire Department with Hose Company 40, the Empire. He was a member of the Jefferson Market Guard and a judge of its target excursion on Christmas Day, 1857, an officer of the Gotham club 1861–64, and in 1876 a director of the North River Insurance Company. Born January 6, 1818, he died April 27, 1893, at his 19 Christopher Street residence.

John M. Murphy: According to Wheaton, he was a “hotel-keeper” and one of the original Gotham BBC members of 1837. He played in NYBBC anniversary contest of November 10, 1845, in Hoboken. Murphy’s establishment is the Fulton Hotel at 164 East Broadway.

Joseph Conselyea Pinckney: In a celebrated early instance of revolving, or seeming professionalism, Pinckney played a game with the Gothams in 1856 while still nominally a member of the Union of Morrisania. Both the Unions and the Knickerbockers objected publicly. Along with Knickerbocker defector Louis F. Wadsworth, he played with the Gotham in 1857. The next year, back with the Unions, he was one of only three New York players selected for the Fashion Race Course match to play in all three games. Enlisting at the outbreak of the Civil War, he was Colonel of the Sixth New York Militia. In 1863 he was brevetted brigadier general of volunteers for war service. Afterward he served in New York City politics as an alderman. Born and died in New York City (November 5, 1821–March 11, 1881).

Henry Mortimer Platt: Born July 7, 1822, Platt died December 8, 1898. He played a match game in 1854 but otherwise served Gotham Club as scorekeeper. He merits mention because in 1939 his daughter donated the sole surviving badge of the Gotham Base Ball Club, featuring three men at sea in a tub, to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Dr. Franklin Ransom: In the game of June 19, 1846, Dr. Ransom played with the club designated as the New Yorks. In 1838 Dr. Ransom resided at 44 Wall. He was in a medical partnership with Dr. Lucius Comstock but also found time to invent a fire engine with a modified hydraulic system. Dr. Ransom exhibited his fire engine to the City Council in 1841 but came to believe that the city had stolen his design. In 1858 he took a patent infringement lawsuit against the Mayor of New York all the way to the United States Supreme Court, but did not prevail. Ransom was born near Buffalo in 1805 and earned his medical degree in 1832 from what was then known simply as the University of New York. He eventually returned to Buffalo, where he continued to file new patents but slipped into obscurity. He died there on March 25, 1873.

Edward G. Saltzman (Salzman, Salzmann, Saltzmann): Born about 1830 in Jefferson County, New York, he was schooled in Hoboken, New Jersey. Saltzman played second base for the Gotham club of New York for five seasons, from 1852–56 and helped to bring the New York Game to Massachusetts via the Tri-Mountain Club. He brought baseball to Savannah, Georgia, in 1865, forming the Pioneer Club, then returned to Boston two years later and resided there until his final year. He died August 14, 1883, in Brooklyn.48

T. Seaman(s): Playing in NYBBC anniversary match of November 10, 1845, he may be a billiard room proprietor of that name or, more likely, he is one and the same as the later Gotham player and treasurer Seaman Lichtenstein, discussed earlier.

James Shepard: After playing with Gotham, then Alpine BBC in 1860, he was a pioneer in establishing baseball in San Francisco, beginning in 1861.

William Shepard: Brother of James, he also played with Gotham, then Alpine BBC in 1860. Pioneer in establishing baseball in San Francisco, beginning in 1861.

Philip Sheridan: Sheridan Joined the Gothams in 1854 and frequently umpired. Said by Peter Nash in Baseball Legends of Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery to have been buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, but that interred Philip Sheridan is not the Gotham player.

George Washington Smith: A member of the Gotham Club after 1845, he was born and raised in Philadelphia. Smith was considered the only male American ballet star of the 19th century. He went on to become ballet master at Fox’s American Theater. He also served in this capacity at the Hippodrome, where the costume of a dancer under his instruction caught aflame with fatal consequence. In his later years he opened a dancing school in Philadelphia. Born ca. 1820, he died February 18, 1899.

Oscar Teed: Oscar Teed, a celebrated ship’s fastener and oarsman as well as a Gotham player, was born in 1828 and died November 4, 1866. A boat named in his honor ca. 1860 continued to race.

Austin D. Thompson: Born in 1820, Austin Thompson was described in his obituary as “a Connecticut Yankee, who came to New York when a youth and opened a coffee house in Pine street, near the old Custom House. … The coffee house, which was called the Phoenix, was frequented by the notabilities of the neighborhood, politicians as well as business men, particularly Democratic politicians, for Mr. Thompson was a Jeffersonian Democrat of the old school.” As its proprietor, Thompson was the successor to the famed Edward Windust, 149 Water Street (Wall, corner Water). In 1851 his coffee rooms and restaurant relocated from 13 Pine to 25 Pine. It moved again in 1860, this time to 292 Broadway, where it remained until Thompson’s death on June 7, 1892. By then Thompson was “probably the oldest eating-house keeper in the city,” which made him “a man who knew nearly everybody and nearly everybody knew him.”49

Richard H. (“Dick”) Thorn: He played with Empire Base Ball Club in 1856, yet was a representative of the Enterprise Base Ball Club at the convention of January 22, 1857. With Gotham in 1858, he pitched for New York in Game 3 of Fashion Race Course Match that September. He returned to Empire 1859–61, then was with Gotham again in 1862, and the Mutual 1865–68. Since about 1850, a prominent member and revenue collector of the Washington Market Association, Thorn partnered with Lathrop and then Marcley in his produce business in the 1860s. In the 1870s he wholly owned Thorn & Co., 11–13 DeVoe Avenue, west of Washington St. On January 26, 1889 rode on horseback, with Seaman Lichtenstein, in a parade to mark the opening of the West Washington Market. In that year he lived at 233 West 13th Street, but does not appear in New York City directories thereafter, though he did testify at a hearing in 1890.

Tooker: He played outfield in Fashion Race Course Game 3, and later with the Henry Eckford Club. In 1871 he was a director of the Athletic Base Ball Club of Brooklyn. Possibly this is Theodore, son of William Tooker, ship’s carpenter, who joined his brother-in-law George Steers in the shipyards that built the America.

Trenchard: This could be Samuel Trenchard, constable or marshal in various years from 1835 until 1861. In 1846 he resided at 86 Ludlow, and played with the club designated as the New Yorks on June 19, 1846. He also played with Washingtons against the Knickerbockers in match game of June 17, 1851. Born in 1791, he died February 15, 1865 in his seventy-fifth year. This would make him a bit of a graybeard for active play in the 1840s and 1850s, so perhaps he is billiard-hall proprietor Alexander H. Trenchard, at 139 Crosby Street in 1855.

Tuche: After the 1856 season, Porter’s Spirit of the Times reported that the Gotham Club had been organized in the early summer of 1852 with “old ballplayer Mr. Tuche” at its head.50 Other accounts also name Tuche as one of the principals, but his name soon disappeared from the club’s annals and nothing more is known about him.

Abraham W. Tucker: Born in 1793, he was named an honorary member of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club in June 1846, along with another New York Ball Club player, Col. James Lee. In 1822 he operated a “segarstore” at 205 Bowery. In 1837 he resided at 48 Delancey Street. Tucker is believed to have died in 1853–54.

William H. Tucker was a tobacconist in business with his father, Abraham, who was also a player with the New Yorks. They operated at 8 Peck Slip and lived at 56 E. Broadway. In 1849–50 he lived in San Francisco. In Alexander Cartwright’s journal/address book he is listed as: “Wm. H. Tucker 271 Montgomery st. upstairs, San Francisco, Cal.” Tucker appears to have died in Brooklyn, at the home of his son-in-law, on December 5, 1894, in his seventy-sixth year, which would conform to a birth year of 1819 recorded in the 1850 census.

Nicholas “Nick” Turner: He played left field in Fashion Race Course Game 2. A shoemaker, he resided in the Tenth Ward in 1860. He was born in Bavaria, 1831. His first name was supplied by Waller Wallace and Henry Chadwick in Sporting Life in 1889.51

William Vail: He was the tobacconist at 179 Prince Street in 1849. Born in 1817–18, his wife Mary was born in 1822–23, and their children as of 1850 were all sons: William, Francis, Martin, Daniel, George, in descending order of age. He was known affectionately as “Stay where you am, Wail,” for his often disastrous derring-do on the base paths. In later years he played with Knickerbocker.52

Gabriel Van Cott: Gabriel acted as umpire for Gothams rather than player. There were a few Gabriels in the Van Cott family, but it appears most likely that this one was a cousin of Thomas and William. Another member of the family, Cornelius C. Van Cott (1838–1904), was the owner of the New York Giants of the National League from 1893 through 1895.

Theodore S. Van Cott :The son of Thomas, Teddy Van Cott later served in the Civil War and died in a home for old soldiers on August 23, 1905.

Thomas Van Cott: Thomas G. (1817–94), who married Harriet Murphy, was the Gothams’ best player in the 1850s, and the great pitcher of all New York ball clubs. The Elmira Gazette obituary of December 19, 1894, called him “The Father of Baseball” and the first man to pitch a curved ball. He was a bookmaker in later years, at the Saratoga Track.

William H(athaway) Van Cott: This brother of Thomas was born September 26, 1821, in New York City, and died June 30, 1908 in Mt. Vernon, New York. He played in Fashion Race Course Games 1 and 2. Elected first president of the National Association of Base Ball Players when it formally organized in 1858, Van Cott was a lawyer and justice by profession. He continued his family’s interest in trotters and began in the stabling business before entering the law. As Justice Van Cott he served sixteen years on the bench. His New York Times obituary reported that his efforts to rid New York of gangs led to two attempts to burn down his house.53

Harry B. Venn: Venn played in NYBBC anniversary match of November 10, 1845, and was a noted fireman with Columbian 14 and the proprietor of the venerable (1778) Gotham Saloon beginning in 1830, when he left his porterhouse at 13 Ann Street and took his first lease at the property. His successor in the lease, S.W. Bryham, transformed the cottage in 1836 to become the Bowery Steam Confectionary and Saloon. By 1842, under new ownership, it was renamed the “Bowery Cottage,” and was the headquarters for firemen, sporting types, and Bowery B’Hoys. Venn resumed his proprietorship sometime before 1845. Behind the bar at the Gotham was a case with the gilded trophy balls from victorious Gotham Base Ball Club matches. (These survived, amazingly, and were sold to collectors in the 1980s; it would be pleasant to think that the Gotham rules survived too!) The back-bar also featured a big gilt “6” taken from the Americus engine (the inspiration for Christy Mathewson’s nickname, “Big Six”). Boss Tweed was a regular patron at the bar. The Gotham Cottage was demolished in 1878, and Venn died a year later, on March 15, 1879. A contemporary wrote that his memorial might be inscribed: “Here lies one whose name was writ in whisky.” Much more could be written about Venn and the Gotham Cottage, but suffice for now this snippet from a long paean to the demolished house by Col. Thomas Picton in the Clipper on June 1, 1878:

Harry B. Venn: Venn played in NYBBC anniversary match of November 10, 1845, and was a noted fireman with Columbian 14 and the proprietor of the venerable (1778) Gotham Saloon beginning in 1830, when he left his porterhouse at 13 Ann Street and took his first lease at the property. His successor in the lease, S.W. Bryham, transformed the cottage in 1836 to become the Bowery Steam Confectionary and Saloon. By 1842, under new ownership, it was renamed the “Bowery Cottage,” and was the headquarters for firemen, sporting types, and Bowery B’Hoys. Venn resumed his proprietorship sometime before 1845. Behind the bar at the Gotham was a case with the gilded trophy balls from victorious Gotham Base Ball Club matches. (These survived, amazingly, and were sold to collectors in the 1980s; it would be pleasant to think that the Gotham rules survived too!) The back-bar also featured a big gilt “6” taken from the Americus engine (the inspiration for Christy Mathewson’s nickname, “Big Six”). Boss Tweed was a regular patron at the bar. The Gotham Cottage was demolished in 1878, and Venn died a year later, on March 15, 1879. A contemporary wrote that his memorial might be inscribed: “Here lies one whose name was writ in whisky.” Much more could be written about Venn and the Gotham Cottage, but suffice for now this snippet from a long paean to the demolished house by Col. Thomas Picton in the Clipper on June 1, 1878:

“The Gotham” became, moreover, extensively known in connection with our national pastime, as beneath its roof was held the first general convention of baseball players, one of the earliest clubs in existence deriving its significant title from this snuggery in the Bowery. “The Gotham” Club [as re-formed in 1852] was a large association from the hour of its inception, organized through the election of Judge William H. Van Cott as president, and Gabriel Van Cott as secretary, with a roll of influential members, principally business men, embracing Harry B. Venn, Seaman Senchenstein [sic], James Forsyth, Joseph Foss, John Baum, George Montjoy, William Johnson, Edward Turner, E. Bonnell, Bates, Tooker, and a host of other notables. Its first playing members distinguishing themselves were Tom Van Cott, Sheridan, McCluskey [McClosky, “an engineer of the Fire Department,” as George Zettlein recalled, in fact John McCosker, who played catcher with the Gothams in 1858], Cudliffe [Cudlipp], and William Burns, its pitcher [catcher?], afterwards lost at sea upon the Central America, wrecked in the Pacific [sic].

Louis F. Wadsworth: Born in Connecticut in 1825, he commenced to play baseball with the Washingtons/Gothams in 1852. After a few years with the Knickerbockers (1854–57) he returned to the Gothams, whom he represented in Fashion Race Course Games 1 and 3. One of the veteran Knicks, in recalling some of his old teammates for the New York Sun in 1887, said:

had almost forgotten the most important man on the team and that is Lew Wadsworth. He was the life of the club. Part of his club suit consisted of a white shirt on the back of which was stamped a black devil. It makes me laugh still when I recall how he used to go after a ball. His hands were very large and when he went for a ball they looked like the tongs of an oyster rake. He got there all the same and but few balls passed him.54

His time with the Knickerbockers, and his crucial role in affixing nine innings and nine men to the rules of baseball, are covered at length in Baseball in the Garden of Eden. Dissipating riches and fame, he died a pauper in the Plainfield Industrial Home in 1908.

William Rufus Wheaton: discussed amply above.

Robert F. Winslow: Robert F. Winslow, a lawyer, played in NYBBC anniversary game of November 10, 1845, Hoboken. In the game of June 19, 1846, Winslow played with the club designated as the New Yorks, and played center field for Gothams in mid-1850s. He and his son Robert Jr. played for the Gotham in the match against the Knickerbockers that commenced on July 1, 1853 and, after a rain interruption, concluded on July 5. In 1854, an Albert Winslow played with the Knickerbockers. Some evidence points to Robert Jr.’s earlier demise, but the Robert Winslows are the only father-son pairing of that surname in New York at the time.

George Wright: He joined the Gotham juniors when he was sixteen, in 1863. One year later he graduated to the senior team and was the club’s regular catcher. He also caught for the club in 1866 under the name of “George” before transferring his allegiance to the Union of Morrisania, where he converted to left field and then shortstop. Born in 1847, George Wright was perhaps the greatest player of the nineteenth century and certainly its first national hero. He died in 1937, four months before his election to the nascent Baseball Hall of Fame.

Harry Wright: The Civil War so decimated the Knickerbockers’ schedule that Wright (1835–95) decided to leave them and join the Gothams in 1863–64. But by the next year he had tired of baseball and resumed his 1850s career, as a cricketer, in Cincinnati, Ohio. He had to wait longer than brother George to enter the Baseball Hall of Fame (1953). Leaving his post as the Cincinnati Cricket Club professional in 1867, he was persuaded to take the helm of the Cincinnati Base Ball Club. The rest is history.

William P. Wright: With Gothams in 1865, played in five games. Not related to Harry and George. Appears to have gone to Cincinnati with Harry Wright at year’s end. With that city’s Buckeye club in 1868–69, Live Oak in 1870.

Other Club Members: John Drohan, Joseph E. Ebling, Hackett, J.A.P. Hopkins, N.W. Redmond, Charles S. Riblet, Peter Roe, Albert Squires, Cornelius Stokem, Andrew Whiteside.

JOHN THORN is the Official Historian for Major League Baseball. He is the author of too many books.

NOTES

1 For a full discussion of these three individuals, see the present writer’s Baseball in the Garden of Eden (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011).

2 His degree from Yale is reported in an untitled article in the Connecticut Courant, August 24, 1835, 3. His medical degree is reported in “Harvard University,” The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, September 26, 1838, 127. His work as an attending physician in New York is reported in “New York Dispensary,” The New-York Spectator, February 27, 1840, 1.

3 “Dr. D. L. Adams; Memoirs of the Father of Base Ball; He Resides in New Haven and Retains an Interest in the Game,” The Sporting News, February 29, 1896, 3.

4 “How Baseball Began: A Member of the Gotham Club of Fifty Years Ago Tells About It,” anonymous journalist interviews William Rufus Wheaton, San Francisco Examiner, November 27, 1887, 14.

5 “City Intelligence,” New York Herald, March 2, 1857, 8. Eden, 51–53.

6 New-York Evening Post, April 13, 1805, 3.

7 National Advocate, April 25, 1823, 2.

8 Eden, 80–81.

9 Peverelly, Book of American Pastimes, 340.

10 Col. Thomas Picton, “Among the Cricketers,” in Fun and Fancy in Old New York: Reminiscences of a Man About Town (William L. Slout, editor; Borgo Press, 2007) 140.

11 New-York Mirror, July 15, 1837, 23.

12 Ibid.

13 New-York Mirror, July 15, 1837, 23.

14 Commercial Advertiser [from New-York Gazette of that morning], November 13, 1820, 2.

15 Cuyp Obituary, New York Herald, July 13, 1871. Also, Picton, “The New York Cricket Club,” in Fun and Fancy in Old New York, 133–43.

16 Picton, “Among the Cricketers,” in Fun and Fancy in Old New York, 140.

17 Spirit of the Times, March 16, 1844, 37.

18 New-York Gazette, March 3, 1803.

19 New-York Morning Post, September 19, 1788. Also, New-York Daily Gazette, April 20, 1789.

20 American Citizen, March 7, 1806.

21 Peverelly, Pastimes, 342–43.

22 Henry Chadwick, Beadle’s Dime Base-Ball Player: A Compendium of the Game, etc. (New York: Irwin P. Beadle and Co., 1860), 6.

23 “The Military Spirit in New York…The Target Companies on Thanksgiving Day,” New York Weekly Herald, December 14, 1850, 397; also, The Subterranean, October 25, 1845, 2

24 New York Illustrated (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1870), 40–41.

25 Peverelly, Pastimes, 346.

26 Albert Spalding Baseball Collections, Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York, Club Books 1854–1868 at the New York Public Library.

27 Spirit of the Times, October 21, 1848, 414.

28 Randall Brown, “How Baseball Began,” The National Pastime 24 [Cleveland: SABR, 2004], 51-54.

29 “The Old Atlantics of Fifty Years Ago,” 1905 clipped article, perhaps from Brooklyn Eagle, otherwise undated. Albert Spalding Baseball Collections. Chadwick Scrapbooks, Volume 5. Chadwick quotes from a letter he received from Commerford. Also, Auburn Citizen, September 22, 1911, reprinted from New York World.

30 Auburn Citizen, September 22, 1911.

31 Albert Spalding Baseball Collections, Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York, Game Books 1845–1856 at the New York Public Library.