Professional Baseball Comes To Toronto To Stay: The Toronto Baseball Club In The Eastern League, 1895

This article was written by David Siegel

This article was published in Our Game, Too: Influential Figures and Milestones in Canadian Baseball (2022)

The first game played by the Toronto-based professional baseball team that ultimately became the Maple Leafs took place on April 29, 1895, and marked the beginning of a proud franchise that would play in the International League (and its predecessor) continually for 72 years.

The first game played by the Toronto-based professional baseball team that ultimately became the Maple Leafs took place on April 29, 1895, and marked the beginning of a proud franchise that would play in the International League (and its predecessor) continually for 72 years.

TORONTO OF THE 1890S

During the nineteenth century, Toronto went from being an unincorporated frontier settlement on the harbor between two semi-navigable rivers to attaining full-fledged metropolitan status. At the beginning of this period, it would have been optimistic to say that it had roughly the same status as Newark (later Niagara on the Lake), Kingston, and London (the aspiring capital located on the Thames River). By 1900 Toronto was eclipsed by only Montréal, a rivalry that would continue through the twentieth century.

How did Toronto achieve this metropolitan status? Metropolitan status has been defined as “the dominance of an urban centre over an adjacent area or hinterland.”1 This dominance is economic, political, cultural, and social.

By 1890, Toronto had become the second largest city in Canada. With a population of 181,000, it ranked second to Montréal,2 and it was continuing to grow rapidly. It had doubled in area in the seven years between 1883 and 1890 by spreading its tentacles north and taking in the outlying suburb of Yorkville and beyond.3 Its population more than tripled between 1871 and 1895. Some of this came from the added territory, but it was also a product of in-migration from other countries and from within Canada, as well as natural increase.4

The city was large enough to develop specialized sectors – the transportation sector on the lakeshore; the financial sector around King and Bay; an emerging but thriving retail sector centered on the new Eaton’s and Simpson’s stores at Yonge and Queen; and factories located in the east end near the harbor at the mouth of the Don River, and in the west end near the railway lines. The factories provided steady employment to large numbers of men who formed unions, which led to improved wages, better working conditions, and shorter hours of work.5 This produced an emerging middle class that had the time and money to spend on entertainment like sports.

It was large enough to support several newspapers. They came and went fairly quickly, but some of the names are recognizable today – Evening Telegram, Evening Star, the Globe, and the Daily Mail and Empire.6

Electric lighting was replacing gaslights, and telephones and telegraph were the modern means of communication. As of 1894, all the previous horse-drawn streetcars were replaced by electric streetcars,7 making getting around the city much easier and quicker.

Even the blemish on this pristine landscape had a metropolitan tone. Toronto was large enough to attract diverse groups of people who did not always agree on important issues. It became the scene of bitter division based on language, religion, and race. (Race at this point referred to the English and French races.) These fights played out not only in the legislature in clashes over issues like education, but they also found their way onto the streets in the form of bitter confrontation.8

SPORT IN THE METROPOLITAN CITY

Looking back at this time, it is difficult to determine the role that sport played in society. There was some interest in baseball, as illustrated by the oft-told story of the 11-year-old boy who was offered the option of paying a fine or going to jail for the grave offense of playing ball in the street.9 Linda Shapiro suggests that “[b]aseball began in Toronto about 1875 with two semi-professional clubs known as the Dauntless and the Clippers.”10 Louis Cauz argued that cricket was popular because it was a British import, whereas baseball was an interloper from the United States. This meant that “for many years the game was not highly regarded by the better class of Toronto citizens.”11

There was clearly an emerging interest in sport generally and baseball particularly. This might have been a reflection of the changing work world, as the hardscrabble earlier times were giving way to the luxury of regular, fairly well paid factory employment, while improvements in the streetcar system made it easier to attend games.

As Toronto developed into a metropolitan city with dominance over the hinterland, it was not surprising that this dominance was also exhibited in baseball. Toronto had joined the nearby Canadian cities of Guelph, Hamilton, and London to form a Canadian League in 1885, but this lasted only one year.12 As the metropolitan city, Toronto needed higher status, so it placed a team in the International League in 1886 (not the same as the later International League), but this team folded part way through the 1890 season – not an unusual circumstance at the time. Toronto was without a professional team from 1890 until it joined the Eastern League in 1895. This franchise played in that league (and its successor International League) until 1967, when the team was moved to Louisville, Kentucky. It was not the major leagues, but it was the highest minor-league level, which put Toronto above most other Canadian cities that flirted with teams in the lower minors, and on the same level as its rival, Montréal, which had a team in the same league from 1928 to 1960.

This was the environment in 1895 when Toronto’s new professional team entered the Eastern League.

THE MINOR LEAGUES OF THE 1890S

Chronicling the early years of minor-league baseball is not easy. Neil J. Sullivan summarized the situation well: “During the 1880s and 1890s, minor leagues came and went at a dizzying pace. A few survive to the present day, but most collapsed in futility.”13 William Humber provides an idea of how complicated the terrain looked for Canadian teams.14 It seems that new teams and leagues emerged and disappeared each season, providing virtually no continuity. It must have been difficult for fans who might develop loyalty to a local team that would disappear after one year.

The Eastern League had functioned since 1884.15 The hierarchy of minor leagues was not as well defined then as it came to be in later years, but the Eastern League seems to have been the top tier of the minor leagues. It drew players on the way up from the New England and New York State Leagues, and it sometimes lost its better players to the National League. It changed its name to the International League in 1912 and existed under that title until 2020, when Major League Baseball demolished the existing minor-league system.

THE FIGHT FOR THE FRANCHISE

The size and growing population of Toronto made it ripe for a professional baseball franchise. The city had had a franchise before starting in 1885, but it failed in 1890. In 1894 there was discussion of Toronto having a National League franchise, even though the 12-team league was then working toward contraction rather than expansion.

When the Eastern League held its annual meeting in New York City on December 5, 1894, it had some important decisions to make. Several teams had dropped out of the league at the end of the previous season, so there would need to be new teams in the league for the 1895 season.16

It seemed a foregone conclusion that Toronto would be awarded a franchise,17 but it was such an attractive location that there were at least four contenders at the league meeting jockeying for the franchise. All four contenders were represented by experienced managers, but three had no real ties to Toronto. The Toronto proposal was from a group of local capitalists fronted by W.J. Smith, identified as “owner of the grounds,” and Chas. Maddock, identified as “keeper of the grounds,” with no explanation of that cryptic title.18 The newspaper stories of the time did not provide much information, but two of the capitalists were identified as Al. De Roy and Peter Ryan (with no further identification). W.J. Smith was from a family that had significant business operations in the city’s east end.19 Charlie Maddock was well-known in Toronto baseball circles.

The bids were identified with the manager who was fronting the bid. The newspaper descriptions were worded to suggest that the league was deciding among the four managers, without much regard to the financial backing. There was no indication in the newspapers that the suitors presented a business plan or any financial information. The leagues were in heavy competition with one another to attract teams, so it is possible that they did not want to discourage potential new teams by asking too many questions. This could explain why so many teams lasted for only part of a season before folding.

No details of the discussion are available, but the newspaper stories indicate that the three contenders without Toronto ties accepted the inevitable and stepped aside.20 Toronto had its Eastern League franchise.

For the first three years of its existence, the team played at Riverside Park, just east of the Don River, close to the corner of Queen and Broadview at a small street called Baseball Place which remains as the site of the Riverside Square Condos. The team played here until 1897, when it moved to Hanlan’s Point on Toronto Islands.21

With the business side of the franchise in place, the next step was to assemble a team.

THE TORONTO BASEBALL CLUB

It was clear that Toronto’s 1895 entry in the Eastern League was a brand-new team that did not build on any previously existing team in Toronto. The manager, Charlie Maddock, had a strong connection with baseball in Toronto, but he conducted his search for players in New England and the state of New York. A few Canadian players were given trials with the team, but only one was from Toronto.22

The newspapers usually described the Toronto team as the “Toronto Baseball Club” or just “baseball team” in the absence of a clearly defined nickname. Sometimes the newspapers referred to the “Torontos,” but it was unclear if this was a nickname that the club espoused or merely journalistic license. For example, there were also references to one of the Boston teams as the “Bostons.” Marshall Wright’s The International League23 and the Baseball-Reference.com website refer to the 1895 team as the Toronto Canucks, which was a nickname used by an earlier Toronto team. Eventually, the team became known as the Maple Leafs; some sources say this occurred in 1896,24 1902, or some other date. Baseball-Reference.com begins using the Maple Leafs appellation with 1899.25 The research undertaken for this article related to the 1895 team included extensive review of several newspapers, and found that the usual reference to the team was “Toronto Baseball Club,” with infrequent use of “Torontos.” No newspaper story in 1894 or 1895 was located that used the nickname “Maple Leafs” or “Canucks” to refer to the Toronto team. At the time the Guelph Maple Leafs were being feted as the champions of Canada; having another Maple Leafs would have been confusing.

There was nothing like an expansion draft in those days, so Maddock was on his own to find players. There was never any mention of a coaching staff or any other assistance. Maddock was aided in his search by the fact that the lower minor leagues did not seem to have any equivalent of a proper reserve clause, so he was free to recruit players from the lower minor leagues like the New York State League and the New England League. Of course, elevating all his players from a lower minor league guaranteed that his lineup would be weaker than the mixture of experienced and newer players found on the other teams.

The newspapers carried stories of Maddock traveling around New York and the New England states signing individual players here and there. Supposedly the owners of the club had given him free rein to spend what he needed,26 but even then he lost some players. However, Maddock was an experienced manager, and by March he had assembled a team.

He described his players as having “first-class reputations in the past, and whose habits for sobriety will compare favourably with any other club in the league.” His on-field aspirations seem a bit restrained: “[The] sole aim of my managerial ability [is] to keep Buffalo in the rear, as we have always done in the past.”27

The league held a meeting in New York City on March 14-16, 1895, to finalize the schedule and handle other league business.28 Teams would play 112 games. Toronto’s first game would be on April 29 at Springfield, Massachusetts, its home opener would be on May 13 against Scranton, and its final game was scheduled for September 14 in Buffalo.29 At this point, it was made clear that “[t] he Toronto Club will under no circumstances play Sunday games.”30 Of course, if they had played on Sunday it would have been difficult to get to the games with no street cars operating.31

Spring training was quite different then. Major-league teams went off to exotic spots like Hot Springs, Arkansas, or Birmingham, Alabama.32 In the absence of a farm system, the minor leagues were on their own for spring training, and most teams did not have much money. For the Toronto team, spring training consisted of arriving in Elmira, New York, two days before the team’s first exhibition game against the local team.33 There were some hiccups along the way. Maddock picked up the team uniforms in Toronto and headed off to Elmira with some players. However, he was surprised when he was assessed $18 in duty on the uniforms that he carried with him.34 After two days of practice in Elmira, the team traveled around New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts playing games. There was a semi-established schedule; sometimes scheduled games disappeared because the team disbanded, but other teams were found.

The team gradually worked its way to Springfield, where it played its first league game on Monday, April 29, 1895.

OPENING DAY LINEUP

TORONTO AT SPRINGFIELD, APRIL 29, 1895

Charlie Maddock, manager, was well known in Toronto baseball circles. He had managed the city’s 1890 entry in the International League which ceased operating in the middle of the season.35 He was described as having a “modest exterior,” but being a “stern disciplinarian.”36 He “had been a member of the famous Maple Leafs of Guelph when it claimed the world championship. Maddock had gnarled, twisted fingers as catchers in those days didn’t wear gloves.”37

It is worthwhile to think about Maddock’s role as manager. First of all, there is no mention of coaches, trainers, traveling secretaries, or clubhouse attendants. Presumably these duties fell to the manager. As mentioned earlier, Maddock played the role of promoter in making the case for having the franchise awarded to Toronto, then he took on the role of scout when he was beating the bushes to find players, general manager when it was time to sign players, and publicist when he sent telegrams to the local newspapers about his activities. Then there was the earlier cryptic comment about his being “keeper of the grounds.” Clearly, the role of manager was different in 1895 from how we think of it today.

Ed or Ned Crane, pitcher. Sad story. Ed “Cannonball” Crane was revered early in his career as an incredibly hard thrower. “He was a key factor in three consecutive pennant winners (1887-1889) in Toronto and New York.” By the time he found his way back to Toronto in 1895, he had discovered hard liquor, sedatives, and high living, and the “cannonball” sobriquet had been replaced by “fat boy.” “He appeared in 29 games, went 7-18, and was released in July.” The next year, he was found dead in a hotel room in Rochester, New York, victim of a drug overdose.38

Fred Lake, catcher, was born in Nova Scotia, but his family moved to Boston when he was 2 years old. He spent most of his lengthy career in the minor leagues, but he did accumulate 125 at-bats in the majors to get a .232 batting average.39 He did better than this in Toronto, where he played 96 games and hit 343.40 He also managed Boston teams in the National and American Leagues.41

Charles William “Luke” Lutenberg, first base, was born in Quincy, Illinois, in 1864, turned pro in 1886, and was much traveled, having played in Quincy; Oakland, California; London, Ontario; Macon, Georgia; Mobile, Alabama; Memphis, Tennessee; and Evansville, Indiana.42 He was in the majors for one year with Louisville in 1894, batting .192.43 In 1895 he appeared in 105 games for Toronto, batting .312 and hitting 4 home runs.44 He continued his playing career in the minors for a few more seasons after 1895, but there is some evidence that he was distracted by the fact that his billiard parlor in Quincy was doing so well.45

Arthur Sippi, second base, was the manager of the London Alert team when he was recruited to come to Toronto. He was one of the few Canadians on the team. He played in 38 games for Toronto, hitting .235.46 His name is found in some baseball statistics websites, but there is no evidence that he played professional baseball before or after his short stint in Toronto.

Judson Smith, third base, was born in Green Oak, Michigan, and was well traveled before he arrived in Toronto.47 In 1895 he was the best hitter on the team, although his precise average is in dispute.48 However, it is clear that he led the league with 14 home runs.49 “Smith fashioned a 20-year career in professional baseball that took him to all corners of the continent from Toronto to Los Angeles and seemingly everywhere in between. … Smith played in well over 2,000 professional games, but only 103 of them were at the major-league level. Smith’s career reflected a pattern: He showed enough promise to get separate trials with four different National League teams, but each time was found wanting and returned to the minors.” While playing, he studied dentistry at The Ohio State University, and he set up a successful dental practice in Los Angeles when he retired.50

Gene DeMontreville, shortstop. His name was also rendered as Demontreville, Demont, or Dermont. He had played 29 games in the Eastern League in 1894, and led all shortstops with a fielding average of .898.51 In 1895 he played 112 games in Toronto, batting .316 and stealing 40 bases,52 before moving on to play 12 games for the Washington Senators in the National League. He went on to play parts of eight seasons in the National League, compiling a .303 batting average and stealing 228 bases before finishing his career in the minors. He also managed for three seasons in the minor leagues.53

Jack Meara, left field, had a reasonably good year for Toronto in 1895. He played in 70 games and hit .256 with 26 stolen bases.54 There is no further information about him in the standard baseball databases.

William Millar “Bunk” Congalton, center field, was born in Guelph, Ontario, but was a much-traveled journeyman player. Toronto was his first stop, and it did not go well, as he was released after 13 games with a .186 average.55 He played in the majors for four years and hit a respectable .292, but he could not stick anywhere because he was so inconsistent.56 After he retired from baseball, he lived in Cleveland, where he suffered a heart attack while attending a game at Cleveland Stadium, and died several days later.57

James Patrick “Doc” Casey, right field. At 5-feet-6 and 157 pounds, he was described as “almost a midget,” but a good ballplayer.58 In 1895 he played in 95 games for Toronto and hit .274.59 He played in Toronto for four years, before going on to a 10-year major-league career in which he hit .258.60 He also served as a player-manager and manager in the minor leagues.

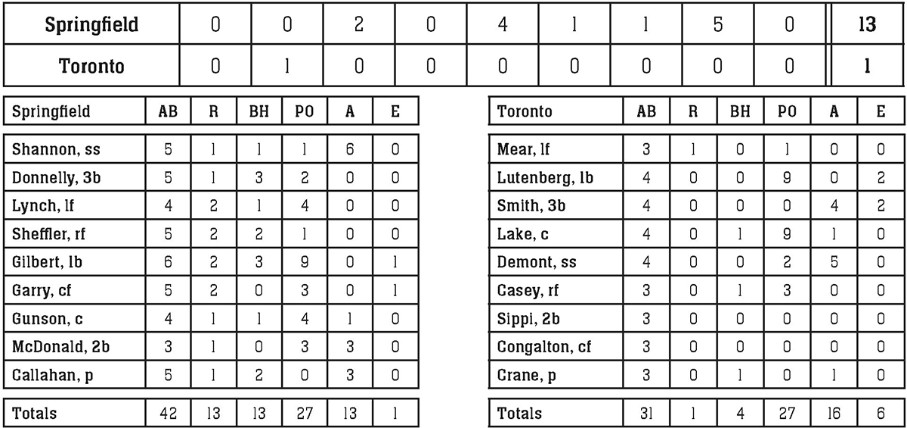

THE GAME

There was some question whether the game would be played because Springfield had experienced a spring flood, but the water receded enough to allow the game to proceed, although there was reference to the field being slippery.

The story in the Globe reads like a foretaste of something that Damon Runyon would write 30 years later:

Eighteen hundred people saw the Eastern League championship season opened with a rush in this city to-day by the Torontos, the newest members of the league, and the same number of people went home happy at the end of the game after seeing the visitors easily defeated by a score of 13 to 1.61

The box score of the game was reported in several newspapers,62 but there seems to be nothing like a scorecard or detailed list of all plays. The Globe provided some narrative of the major plays. Understandably, there is a precise description of how Toronto scored its lone run, but much less detail about the 13 scored by the Springfield Ponies.63

Toronto scored its only run in the bottom of the third inning. (The home team could choose if it wanted to bat first or last, and in the Dead Ball Era, there was an advantage to batting first when the ball was still fresh.)

Ed Crane, the Toronto pitcher, opened the inning with a hit over shortstop, but was forced out on a bunt by Meara. Lutenberg then hit a double that scored Meara. The side was retired without further scoring. There were two additional Toronto hits in the game, including a single by Crane, but no other Toronto player got beyond first base. The Springfield pitcher, Callahan, was obviously effective in giving up only four hits and one walk, but he struck out only two. Callahan also helped himself by hitting a home run.

The Ponies scored their 13 runs on 13 hits, which seems quite economical. However, they were aided by five Toronto errors, which explains the fact that only five of the 13 runs were earned. The Globe’s correspondent was pretty ruthless about the fielding prowess of certain Toronto players: “Lutenburg made a couple of inexcusable errors at first, which counted high in the score, but the weakest spot in the team is evidently at centre field where Congalton proved slow in judging flies and showed poor judgment in throwing to bases.” Crane did not help his own effort by giving up five bases on balls, hitting two batters, and throwing a wild pitch. He struck out only two batters.

Several things stand out about this game from the perspective of a present-day viewer. There were four strikeouts out of 54 total outs. Crane pitched a complete game while giving up 13 runs on 13 hits. There was no such thing as a relief pitcher, so Crane had the honor of pitching a complete game while losing 13-1. Both pitchers started the season with a good batting average. Callahan was 2-for-5 with a home run. Crane was 1-for-3. The time for this 14-run game was 1:55.

WHAT FOLLOWED

The team continued its 12-game road trip, finishing 3-9. It played its first home game on May 13, 1895. Alas, its fortunes were not changed by home cooking. The team lost 2-1 to Scranton before 1,500 fans, “including a large number of ladies.” However, attendance was held down by the wintry weather.64 Attendance could also have been held down by the fact that there did not appear to be any paid advertising in the local newspapers, even though other leagues, even amateur ones, advertised in the papers.

The Toronto Baseball Club finished the season in seventh place in an eight-team league with a record of 43-76.65 This put the team five games ahead of the other expansion team, Rochester.66 Maddock was replaced during the season when the team had a record of 14-34. He was succeeded by Jack Chapman, who led the team to a 29-42 record. Chapman was not at the helm for the next season.67

The team had an inauspicious start, which is not surprising for an expansion team. However, it was the start of a 72-year run in the Eastern/ International League. In an era when leagues seemed to have a revolving door for entering and exiting teams, this was quite an achievement.

DAVID SIEGEL has been a member of SABR since 2006. After 40 years as a professor of political science and an administrator at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario, he has now turned his attention to doing research on baseball.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank staff at the Brock University library for their assistance in locating newspapers and other material.

Box score

Earned runs: Springfield 5; Toronto—1.

Total bases: Springfield, 20; Toronto—5.

Sacrifice hits: Donnelly, Sheffler.

Stolen bases: Shannon 2; Lynch 2; Sheffler, Gunson.

Two-base hits: Donnelly, Callahan, Lutenberg. Three-base hit: Gunson; Home run: Callahan.

First base on balls: Off Crane 5; off Callahan 1. First base on errors: Springfield 4; Toronto 1.

Left on bases: Springfield 9; Toronto 3.

Struck out: by Crane 2; by Callahan 2. Hit by pitcher: By Crane 2. Wild pitch: Crane.

Time—1:55. Umpires—Snyder and Swartwood.

Notes

1 D. C. Masters, The Rise of Toronto: 1850-1890 (Toronto: The University of Toronto Press, 1947), vii.

2 Census of Canada, 1890-91. Volume I. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1893.

3 C.S. Clark, Of Toronto the Good: The Queen City of Canada as It Is (Montréal: The Toronto Publishing Company, 1898), 2.

4 J.M.S. Careless, Toronto to 1918 (Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, Publishers, 1984), 120.

5 Masters, 175-8.

6 Masters, 167-8

7 G.B. deT. Glazebrook, The History of Toronto (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1971), 178.

8 Glazebrook, 161-8.

9 Clark, 5.

10 Linda Shapiro, ed., Yesterday’s Toronto: 1870-1910 (Toronto: Coles Publishing Company Limited, 1978), 102.

11 Louis Cauz, Baseball’s Back in Town (Toronto: A Controlled Media Corporation Publication, 1977), 11.

12 Shapiro, 102.

13 Neil J. Sullivan, The Minors (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990), 20.

14 William Humber, Diamonds of the North: A Concise History of Baseball in Canada (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1995), 201-2, 208-9.

15 Sullivan, 20-21.

16 https://www.basebalI-reference.com/bullpen/Eastern_League#Ontario (Accessed October 16, 2021).

17 “After Toronto’s Franchise,” Toronto Daily Mail, November

18 “Toronto in the Eastern,” Toronto Daily News, December 7, 1894: 2.

19 Leslieville Historical Society, “Smith’s Grounds: A Lost Riverside Athletic Field,” https://leslievillehistory.com/2018/02/01/smiths-grounds-a-lost-riverside-athleticfield/ (Accessed October 17, 2021).

20 “Local Parties Want It,” Toronto Daily Mail, November 20, 1894: 2; Toronto Daily Mail, November 21, 1894: 2; “Toronto in the Eastern,” Toronto Daily News, December 7, 1894: 2.

21 This came to be known as Sunlight Park, but probably not until after the Toronto Baseball Club had departed. Leslieville Historical Society, “Smith’s Grounds: A Lost Riverside Athletic Field,” https://leslievillehistory.com/2018/02/01/smiths-grounds-a-lost-riverside-athletic-field/ (Accessed October 17, 2021).

22 Daily Mail and Empire, February 14, 1895: 2; Daily Mail and Empire, March 29, 1895: 2; Daily Mail and Empire, April 1, 1895: 2.

23 Marshall D. Wright, The International League: Year-by-Year Statistics, 1884-1953 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 1998), 74.

24 Wright, 78.

25 https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=ba731cc5 (Accessed October 16, 2021).

26 Daily Mail and Empire, February 25, 1895: 4; Daily Mail and Empire, April 15, 1895: 2.

27 Daily Mail and Empire, April 11, 1895: 4, 18.

28 Daily Mail and Empire, March 14, 1895: 4; Daily Mail and Empire, March 15, 1895: 2; Daily Mail and Empire, March 16, 1895:4.

29 Daily Mail and Empire, March 15, 1895: 2.

30 Daily Mail and Empire, February 28, 1895: 4.

31 Careless, 183.

32 “SABR Spring Training Database.” https://sabr.org/spring-training-database (Accessed, October 15, 2021).

33 Daily Mail and Empire, March 21, 1895: 4; Daily Mail and Empire, April 15, 1895: 2.

34 Daily Mail and Empire, April 18, 1895: 2; Daily Mail and Empire, April 23, 1895: 5.

35 Cauz, 25.

36 Daily Mail and Empire, April 15, 1895: 2.

37 Cauz, 23. See also Humber, 28-32.

38 Brian McKenna, “Ed Crane,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/ed-crane/ (Accessed October 7, 2021).

39 Don Hyslop, “Fred Lake,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/fred-lake/ (Accessed October 7, 2021); https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=lake–001fre (Accessed October 7, 2021).

40 https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=106d86ad (Accessed October 7, 2021).

41 https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Fred_Lake (Accessed October 7, 2021).

42 Daily Mail and Empire, February 22, 1895: 2.

43 https://www.baseball-reference.com/buIIpen/Luke_Lutenberg (Accessed October 7, 2021).

44 https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=106d86ad (Accessed October 7, 2021).

45 https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Luke_Lutenberg (Accessed October 7, 2021).

46https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=106d86ad (Accessed October 7, 2021).

47 Terry Bohn, “Jud Smith,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/jud-smith/ (Accessed October 24, 2021).

48 Wright, 70.

49 Wright, 70.

50 Bohn, “Jud Smith.” It is clear that Smith had a lengthy career. Whether the precise number of seasons was 19, 20, or 21 is not clear. https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=smith-001jud (Accessed October 27, 2021).

51 Daily Mail and Empire, March 14, 1895: 4. The microfilm was unclear with regard to the fielding average.

52 https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=106d86ad (Accessed October 7, 2021).

53 https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=demont001eug (Accessed October 7, 2021).

54 Daily Mail and Empire, February 14, 1895: 2; https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=-106d86ad (Accessed October 7, 2021).

55 https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=106d86ad (Accessed October 7, 2021).

56 https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Bunk_Congalton (Accessed October 7, 2021).

57 Bill Nowlin, “Bunk Congalton,” https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bunk-congalton/ (Accessed October 7, 2021).

58 Daily Mail and Empire, February 14, 1895: 2.

59 https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=106d86ad (Accessed October 7, 2021).

60 https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Doc_Casey (Accessed October 7, 2021).

61 Globe (Toronto), March 30, 1895: 8. The box score and the description in the following paragraphs come from this article.

62 Daily Mail and Empire, April 30, 1895: 2.

63 Newspaper stories referred to the team as the Ponies. Baseball-Reference indicates that the team was called the Maroons in 1895, but it was called the Ponies both before and after 1895. https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Eastern_League#Ontario (Accessed October 16, 2021.)

64 Daily Mail and Empire, May 14, 1895: 4

65 It was reported earlier that the league had a 112-game schedule. There is no explanation of why the Toronto team apparently played 119 games. All the teams in the League played more than 112 games, but the number varied. Toronto played some exhibition games, and it is possible that those games are included in the total. https://www.statscrew.com/minorbaseball/l-IL/y-1895 (Accessed October 18, 2021).

66 https://www.statscrew.com/minorbasebalI/standings/l-IL/y-1895 (Accessed October 16, 2021).

67 Cauz, 144.