Quicker Than Quick: A 31-Minute Professional Game

This article was written by Wynn Montgomery

This article was published in Fall 2011 Baseball Research Journal

BACKGROUND: The 2010 SABR convention publication, The National Pastime: Baseball in the Peach State, included an article entitled “That Was Quick” describing a professional baseball game that lasted a mere 32 minutes. Based on information in “The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball”1 and a Google-based search for any quicker game (as unlikely as that seemed), the article indicated that this 1910 game remained what a local sportswriter called it at the time—“the fastest nine innings ever played in the organized baseball world.”22 Shortly after The National Pastime was published, SABR member Jim Baker informed the author that a faster game had been played in his hometown of Asheville, North Carolina. He provided supporting documentation, and the following article ensued. The Atlanta Crackers and Mobile Sea Gulls were plenty quick in 1910, but the Asheville Tourists and the Winston-Salem Twins were even quicker six years later.

Baseball history was made at Oates Park in Asheville, North Carolina, on August 30, 1916, but nobody noticed. In fact, nobody noticed until some 50 years later—and even then the discovery was accidental and did not receive the lasting attention it deserved. On that day, two baseball teams in the Class D North Carolina State League played a nine-inning game in only 31 minutes—one minute faster than the 1910 Southern League game that has long been touted as the fastest game in professional baseball history.3

The game in Asheville pitted the local Tourists against the Twins from nearby Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The local newspaper account the following day understated the game’s historical significance calling it merely “the fastest bit of pastime ever played on [the] local diamond”4 [emphasis added]. The headline labeled the game “farcical,” and the article itself provided little information on the game itself, but enough to substantiate that description. No box score accompanied the story, only a line score by innings documenting a 2–1 victory by the visiting team and identifying the teams’ batterymates. The two Winston-Salem papers added no game details, and one said that “no official score was kept.”5

The game in Asheville pitted the local Tourists against the Twins from nearby Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The local newspaper account the following day understated the game’s historical significance calling it merely “the fastest bit of pastime ever played on [the] local diamond”4 [emphasis added]. The headline labeled the game “farcical,” and the article itself provided little information on the game itself, but enough to substantiate that description. No box score accompanied the story, only a line score by innings documenting a 2–1 victory by the visiting team and identifying the teams’ batterymates. The two Winston-Salem papers added no game details, and one said that “no official score was kept.”5

Only some 200 fans witnessed this historic event—perhaps because it ended before it was scheduled to start. The season was almost over, and both teams were out of the second-half pennant race. Both teams also had trains to catch; Asheville was headed to Raleigh to face the Capitals, and the Twins were going home. Therefore, when Winston-Salem manager Charley Clancy asked his Asheville counterpart to begin the game early, Jack Corbett readily agreed. The game started at 1:28 instead of 2:00, the final out was recorded at 1:59, and the Tourists were on a 2:30 train to Raleigh.6 The first three innings were played without an umpire because Red Rowe, who had that role, arrived only 20 minutes before the announced starting time.7

The limited description of game action makes it clear that this was no ordinary game. The Asheville paper noted that “it is usually the custom after the pennant has been clinched…for [some] other team… to make merry at the last game. The same stunt was pulled here at the end of last season.”8 The Atlanta Crackers had taken a similar approach six years earlier, and the result of their effort received more publicity.

The Crackers, the Tourists, and their opponents showed that the way to play a game at maximum speed involved racing on and off the field to minimize the time taken to change sides between innings. The North Carolina teams seem to have added several fillips that allowed them to set the new speed record. Players sometimes ventured on and off the diamond before the final out was recorded. Pitchers did not always wait for all their teammates to be in position before delivering their first pitch, and both moundsmen “lobbed” their tosses. All batters swung at the first pitch they saw, and after hitting the ball simply kept running until they were tagged out.9 Hence, all three runs resulted from home runs that cleared the outfield walls,10 and no baserunners were stranded.

Although both teams obviously collaborated to minimize playing time, the game’s result must not have been prearranged. The visiting team won, 2–1—as did its counterpart in the earlier fastest game. Had the teams’ sole purpose been to play the games as quickly as possible, they could have arranged for the home team to win, thus avoiding the need to play the bottom of the ninth. Apparently, there are limits to collusion.11

One play personifies the farcical approach to the game: when a Winston-Salem hitter led off an inning with a single to center field and continued running, he drew an errant throw that was heading toward the visitors’ dugout until Frank Nesser, the Twins’ on-deck batter, scooped up the ball and threw his teammate out at second base.12

The description of this play in the local newspaper also illustrates the limited coverage the game received. The attending sportswriter described the action as

having occurred “along about one of the innings,” identified the hitter only as “some Twins player,” and called the on-deck batter “Nerwer.”13 This writer was much more interested in describing certain fans than identifying game participants, reporting that the ladies in attendance were especially disappointed that the game was so short. His eloquent description: “Buxom blondes and brunette belles, fraulines and fraus, all pouted in the same breath that it was ‘perfectly horrid.’”14

Another spectator who was displeased with the record-setting game was L.L. Jenkins, owner of the Tourists. Like the umpire, Jenkins thought he had arrived ahead of game time, only to find that the game was well under way. Unlike most owners, Jenkins chose to pay for his own ticket. He definitely wanted to get good value for his money and thought other fans deserved the same. He didn’t consider a 31-minute game to be an adequate return on investment, so he quickly “assured the fans, in his best oratorical style,”15 that the club would refund their money. Thus, fans who requested and received that rebate saw a once-in-a-lifetime event for free!

What these fans apparently did not see was future major league stars. The absence of a box score and the local sportswriters’ limited attention to detail make it impossible to identify with certainty all the participants in this game. Besides the batterymates and Frank Nesser (aka Nerwer), only two players—Osteen and Adams—are named. Partial (and understandably sketchy) rosters16 for both teams available through Baseball-Reference.com give insight into who might have been on the field that day.

While these rosters included a number of players who had been or would become major leaguers, neither team was blessed with players who would earn lasting fame on the diamond. Two Asheville pitchers—George “Doc” Lowe, the loser of the record-setting game, and Eddie Bacon—eventually had “cups of coffee” in the majors, as did Asheville second baseman Dallas Bradshaw and Winston-Salem infielder Harvey “Hob” Hiller. The Twins’ Ray Rolling, who was playing the last of his 11 seasons in the minor leagues, had played five games for the St. Louis Cardinals four years earlier. Another former major leaguer was behind the plate for Asheville in this historic game; Earle Mack, son of the legendary owner/manager Connie Mack, had played in five games over three seasons for his father’s Philadelphia Athletics. He would not play another major league game, but continued to play in the minors until 1923—a total of 11 seasons.

Two players from these teams made more indelible (albeit brief) marks in the majors. Asheville’s star outfielder in 1916 was Jimmy Hickman, whose .350 batting average led the league and convinced the Brooklyn Robins to bring him up at the end of the season. He already had some major league experience, having played 20 games for the Federal League’s Baltimore Terrapins in 1915, but initially did little to distinguish himself in nine games with the NL Champion Robins. The following year, however, his six home runs tied him with teammate Casey Stengel for the team lead and ranked forth in the National League. His batting average that year was only .219, and he ranked forth in the league in strikeouts (66) and outfield errors (15). His productivity quickly diminished (he hit only one more home run in the majors), and his major league career ended in 1919 after three full seasons.

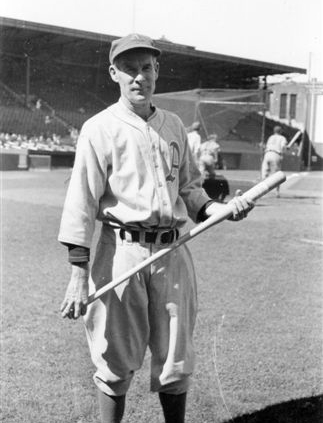

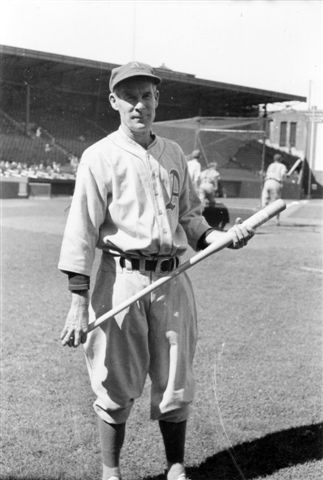

Charles “Whitey” Glazner was the ace of Winston-Salem’s 1916 pitching staff; his victory in the 31-minute game gave him a 21–7 record, but it took a 24–10 record for Birmingham in the Class A Southern Association in 1920 to earn a trip to the major leagues.

He joined the Pittsburgh Pirates late that season and appeared in only two games. His first full major league season (1921) was his best by far. He compiled a 14–5 record for a league-leading .737 winning percentage; his 2.77 ERA was 3rd best in the National League; and his 1.162 WHIP ranked second behind teammate Babe Adams. Glazner never had another winning season, and by 1925 he was back in the minors, where he spent seven more seasons before finally hanging up his glove.

Two individuals involved with this historic game gained more lasting fame. Jack Corbett, who managed the Tourists and who agreed to speed up the game, was a career minor leaguer (mainly at the Class D level) as a player and manager, but he made it to the majors as an inventor. Corbett managed for only one year after the 1916 season, and he eventually moved to California, where he designed and patented a new style of base with a tapered lip on the bottom to grip the infield dirt and a six-inch anchoring stanchion.17 In 1939, these bases, which bear his name (“Jack Corbett Hollywood Base Sets”), became Major League Baseball’s “official bases,” and Jack Corbett had his place in every Big League stadium. He also earned a place in literature (although under a different name) thanks to the later efforts of the 15-year-old youngster who served as Asheville’s batboy during the 1916 season. That young man became a writer, and two of his novels included a fictional baseball player named Nebraska Crane. The batboy and future author was Thomas Wolfe, and his model for Crane probably was Jack Corbett, who had lived for a time in the boarding house operated by Julia Wolfe, Thomas’s mother.18

Despite the record-setting pace and the related historical tidbits, this game went unnoticed for “more than half a century”19—until Dick Kaplan, a writer for the Asheville Citizen, stumbled across the story while searching the newspaper’s microfilm on a different and unrelated topic. Bob Terrell, longtime sports editor and columnist for that same newspaper, told the long-lost story in The Sporting News (April 5, 1969), but some accepted reference works still list the 1910 Atlanta game as the fastest ever played. It is time to give the Asheville and Winston-Salem teams the credit they deserve even though we cannot honor all the players by name. The anonymous writer who chronicled that game was correct when his opening paragraph warned that he could not enlighten us much. We will just have to take him at his word that “it was a good game, what there was of it.”20

WYNN MONTGOMERY, a recent transplant from Georgia to Colorado, is a retired bureaucrat and educator and a recovering workaholic. He has been a SABR member since 1983 and was co-editor of (and contributor to) the 2010 SABR Atlanta convention publication, “Baseball in the Peach State“. His article “Georgia’s 1948 Phenoms and the Bonus Rule” appears in the Summer 2010 issue of the Baseball Research Journal. His baseball interests include the art and the history of the game (especially the 1950s and the Negro Leagues). He has attended games in 55 minor league parks in 22 states and in every major league city except Arlington, Texas.

Notes

1 Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolfe (Eds.), The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Durham, NC, 1993.

2 Tom Akers, Atlanta Journal, September 18, 1910.

3 Wynn Montgomery, “That Was Quick”, The National Pastime: Baseball in the Peach State, SABR 40 (2010).

4 Asheville Citizen, August 31, 1916.

5 Twin City [Winston-Salem, NC] Sentinel, August 31, 1916.

6 Ibid.

7 Bill Ballew, A History of Professional Baseball in Asheville. (Charleston, SC, The History Press, 2007).

8 Asheville Citizen, August 31, 1916.

9 Ibid. and Winston-Salem Journal, August 31, 1916, and Twin City Sentinel, August 31, 1916.

10 Bob Terrell, “Watch It Fly,” Our State (June 2003).

11 E-mail (October 15, 2010) from James G. Baker, the former Asheville sportswriter who called this historic game to the author’s attention and who was a valuable resource throughout the development of this article.

12 Ballew.

13 Asheville Citizen, August 31, 1916.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Asheville’s roster includes Osteen (with no first name) but lists no one named Adams.

17 Ron Schuler, “The Fastest Game,” Ron Schuler’s Parlour Tricks, May 23, 2007 (rsparlourtricks.blogspot.com).

18 Crane appears in The Web and the Rock (1939) and You Can’t Go Home Again (1940) and in an eponymous short story published in Harper’s Magazine (August, 1940). All were posthumous publications. In “Watch It Fly,” Terrell asserts that “Wolfe used his memory of Corbett to embody the player.” Ballew reiterates this relationship in his History of Professional Baseball in Asheville, citing Corbett as “the only player Wolfe wrote about directly.” Wolfe biographer Joanne Marshall Mauldin questions this theory in Thomas Wolfe: When Do the Atrocities Begin? (Knoxville, University of Tennessee Press, 2007), citing information from Edward C. Aswell, Wolfe’s editor, that Wolfe’s relatives told him that “no one among Tom’s childhood acquaintances … could have sat for the portrait of Nebraska” and suggesting that Crane “is a composite of …” three people, none of whom are Jack Corbett. Unfortunately, neither they nor we can ask the only person who can resolve this debate. The answer rests in Riverside Cemetery in Asheville, North Carolina, beneath a homeward-looking angel.

19 Terrell.

20 Asheville Citizen, August 31, 1916.