Retrosheet Begins in Baltimore

This article was written by Jay Wigley

This article was published in The National Pastime: A Bird’s-Eye View of Baltimore (2020)

We baseball fans want the truth. Some of us want to know how well Duke Snider hit in 1957. We want to look it up. And some of us, once we’ve answered that question, begin to wonder if the Duke could hit lefties as well as righties, or not. Then we wonder, perhaps, how much of Duke’s difference makes a difference when it comes to winning games. So, a handful of fans — asking such questions and knowing that data would be needed to search for the truth — began work in the 1970s that brought us to where we are today: baseball data heaven.

We baseball fans want the truth. Some of us want to know how well Duke Snider hit in 1957. We want to look it up. And some of us, once we’ve answered that question, begin to wonder if the Duke could hit lefties as well as righties, or not. Then we wonder, perhaps, how much of Duke’s difference makes a difference when it comes to winning games. So, a handful of fans — asking such questions and knowing that data would be needed to search for the truth — began work in the 1970s that brought us to where we are today: baseball data heaven.

We modern fans have trouble imagining how no one had any landscape of baseball data in the 1970s. To provide any answer beyond The Baseball Encyclopedia’s simple totals and averages, we needed play-by-play information. The Elias Sports Bureau had that sort of data, the official data.1 But Elias’s data were certainly not available to satisfy fans’ curiosity. Elias worked for their own pleasure (both personal and financial) and for their patrons, the league offices of the major leagues. In short, Elias did not share with “just anyone,” at least not publicly.

Beginning in the 1970s, SABR’s Statistical Analysis Committee had more than a few members who wanted access to that quality of play-by-play data. Pete Palmer, Dick Cramer, and David Smith (co-chairs of the committee) wanted to know who did what, and when they did it. Not satisfied with the counting stats and career totals provided by The Baseball Encyclopedia, these studious, serious fans needed play-by-play data for their rigorous baseball analysis.

The first effort to gather such data began in 1983 when Bill James organized an army of volunteers in an effort he dubbed “Project Scoresheet.”2 His idea was to gather play-by-play data through volunteers dedicated enough to record every play of every game and send in their scoresheets. “The Project,” as veterans of that effort still call it, generated enough data and made enough money to collapse eventually under the weight of its success. By the early 1990s, the remaining volunteers ended the Project. But some of them, under the leadership of David Smith, saw potential beyond anything James had imagined.

At a late 1978 SABR (Philadelphia chapter) meeting, Smith had met Carl Lundquist, a retired UPI sportswriter who had saved his professional scorebooks from 460 New York games (all three teams) from 1949–56. Lundquist shared copies of all of them with Smith. Working with David Nichols (another Scoresheet volunteer) in 1988, Smith successfully entered a single Lundquist-scored game into a modified version of the Project Scoresheet software, to prove older games could be captured and coded using the same data format as modern seasons. While James’ original vision had not included computerization of the data, Smith correctly reasoned that if he could aggregate as many games as he could find in a common data format already proven useful, the analysis possibilities would be limitless.

Smith’s personal motives went beyond the desire for simply more data. For Smith, capturing the seasons of the past in an organized way, and making them available for both reflection and analysis, was and is “hugely important. To catalog the basic events of the national game [is] something of a moral obligation.”3 As Jayson Stark sees it, Smith’s idea for Retrosheet eventually made today’s “Baseball-Reference.com and their Play Index possible. It fuels the research that literally thousands of us do every week of every year. And it’s an invaluable resource in every way, the gift that never stops giving.”4

But to get his idea off the ground, Smith needed more scoresheets, lots of them.

Bill James’s public approach had alienated both the insular major league teams and their official statisticians (Elias) so Smith began with a more personal appeal. Smith began contacting other SABR members and Project Scoresheet volunteers, hoping to fill file cabinets with scoresheets for eventual translation into computer data, to be shared via floppy disk. One of the first to reply was Pete Palmer, who promptly introduced Smith to Eddie Epstein.5 This moment was a true breakthrough for Retrosheet because Epstein knew about “the stash.” And Eddie soon learned that his new friend Dave Smith wanted it. Specifically, Dave wanted to copy it.

The stash was a collection of scoresheets for every Baltimore Orioles game since 1954. It wasn’t Eddie’s to share, but he knew how to pitch the idea to the Orioles front office. An early believer in the power of analytics, Epstein had come to work for the Orioles as a consultant in the mid-1980s, using his economics training to help the team make smart contract offers during player salary negotiations. So, while not in the public relations department himself, Eddie knew who was in charge of keeping up “the books.” He knew it was the public relations department who cared about that history and used it to create daily game notes for the broadcast teams and more in-depth articles for all kinds of Orioles profiles and pieces.

Eddie began with the assistant public relations director, Rick Vaughn, asking him to open the Orioles’ books to an outsider. Vaughn, who began with Baltimore in 1984, remembers being “extremely excited” when Eddie first told him about Smith’s project, which would soon have a name: Retrosheet. Vaughn remembers that his boss, Bob Brown, head of Orioles public relations, was also excited, as both men loved the historical aspects of the game. Rick was happy to ask Brown for permission to share all his “working copies” of the scoresheets with Smith. Part of Vaughn’s responsibilities in those days was “to make sure we copied the scoresheet after every game and put it in the loose-leaf binder we had for that season. They were kept in a bookshelf in [Vaughn’s Memorial Stadium] office. The loose-leaf notebooks held up much better than the original scorebooks, but we had those as well. [The original scorebooks] were kept in Bob Brown’s office, and eventually moved to a larger research area at Camden Yards.”6

Vaughn cautions that while he was personally enthusiastic, nothing would have been shared between the team and Retrosheet without Bob Brown’s endorsement. Brown was already an Orioles legend, having joined the team in 1958, alternating as traveling secretary and public relations director during his (eventual) 35-year Oriole career. Brown was chosen as the second recipient of the Robert O. Fishel Award for public relations excellence in 1982 (the first winner after Fishel himself), and there were few PR men in the game with more clout.7 Vaughn remembers, “When I started, I was living in Virginia, and I drove 61 miles each way to Memorial Stadium. The primary reason I took the job was to work under Bob Brown. No one worked harder or cared more about baseball than Bob.”8 By 2000, the Camden Yards press box would be renamed after Brown.9

Vaughn remembers that the mechanics of maintaining and collecting Orioles scoresheets went something like this: “The current [season] book was kept in the PR bag that we had with us for home and road games. Before the PR staff started traveling (in 1988 during the 0-21 start), the traveling secretary would maintain the scorebook on the road. I was the primary user because I was responsible for the game notes. I referred to them daily, but Bob and others used them as well, just not as much. We maintained it that way because that is not a project you want to get behind on. It just made sense to make a copy of the scoresheet and file it after every game. That was how thorough Bob was.”10

According to Vaughn, Smith had “someone” come by and borrow all 30 binders during the 1988–89 off-season. Smith recalls, “The person who came by to borrow the binders was me. I drove to Baltimore in a huge rainstorm and collected all 30, brought them back to Delaware and copied them, returning them in about a month. [My wife] Amy still talks about seeing the binders on our coffee table and marveling at them, since she had always been an Orioles fan.”11

And so just like that, for only the asking, Retrosheet had over 4,700 games to begin translating into the computer. Smith recruited volunteers to use a new Retro-version of the software by David Nichols and Tom Tippett, based on what they originally created for Project Scoresheet. The benefit of Retrosheet beginning with Baltimore would be evident for years to come, as Bob Brown proved influential with other major league teams reluctant to open their archives to outsiders. Slowly, many of the same teams who had rebuffed James years before would respond to Retrosheet’s more personal approach, and to Bob Brown’s professional reputation, as he vouched for them directly with the front offices and public relations departments of the Phillies, Padres, Tigers, and Mets.12

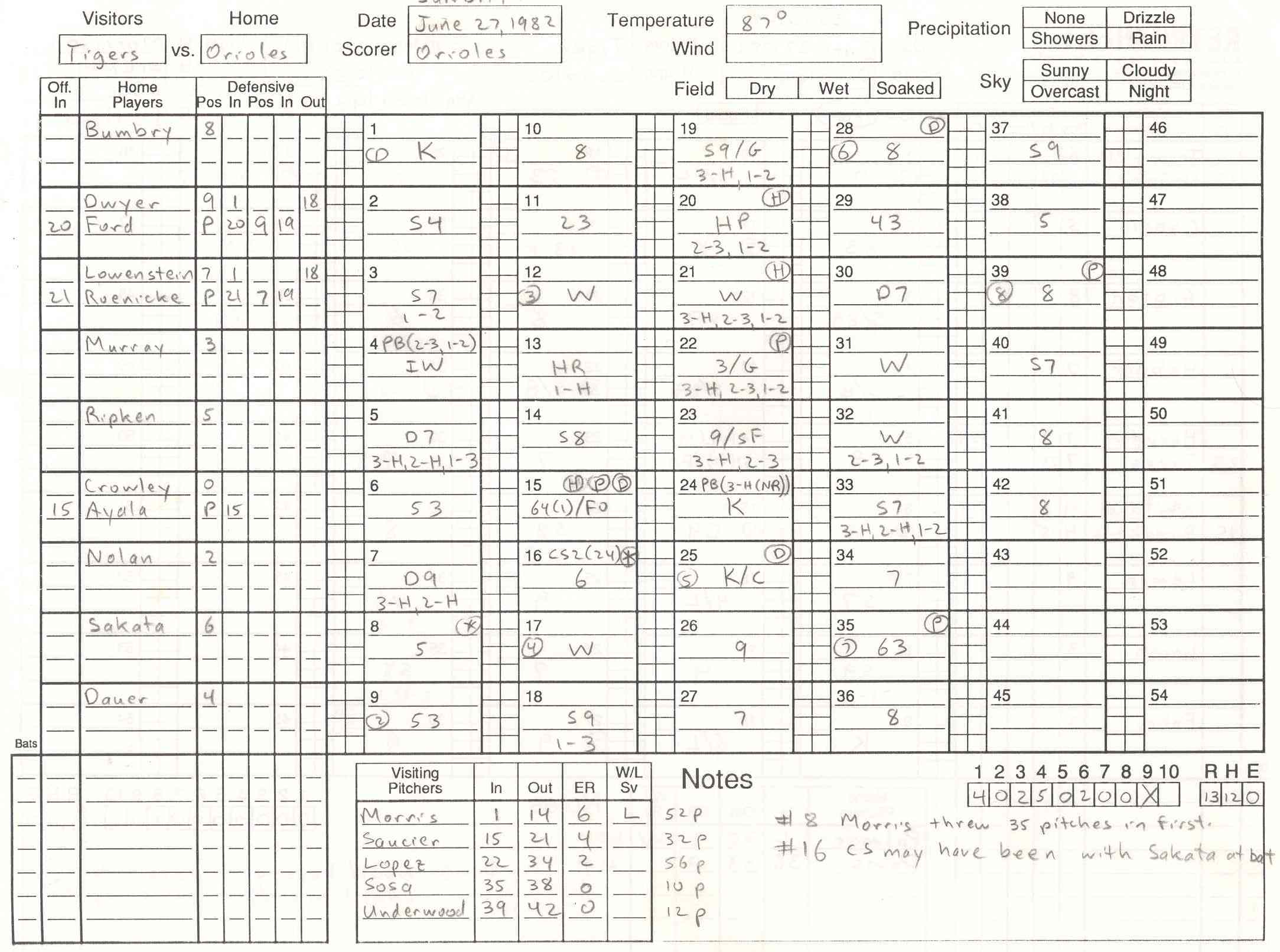

The Orioles data would serve other purposes as well. Retrosheet volunteers over the years became experts on one Orioles game in particular: the June 27, 1982, contest at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium against the Tigers. Smith selected the Baltimore play-by-play in that game to serve as training material for any volunteer wanting to enter data using the Retrosheet format.13

Years later, Bob Brown’s choice to help Retrosheet with data would cost his team a little money. A Retrosheet volunteer discovered a discrepancy in the RBI totals for the 1961 season, resulting eventually in a revision to the official record. Instead of a single winner of the RBI crown that season (Roger Maris of the Yankees), there were in truth two, the other being Oriole Jim Gentile. Gentile remembered his contract negotiations with Orioles GM Lee MacPhail the following season, with MacPhail telling him that if he had won the RBI race, his contract would have been “worth $5000 more.” The Orioles made it right, when then-GM Andy MacPhail (Lee’s son) delivered Gentile the money at a Camden Yards ballgame in the summer of 2010.14

David Smith wouldn’t have an Eddie Epstein in every baseball club’s front office. He would request the support of the president of the National League and even the Commissioner of Baseball in years to come, but ultimately it would be his success with the Orioles, parlayed into introductions to nearly every other team, that enabled Retrosheet to create and deliver the treasure trove of detailed play-by-play baseball data that is available, all for free, at their website today.

JAY WIGLEY first joined SABR in 1999 after discovering Retrosheet in 1996. His earliest baseball memory is of the scoreboard animations at the Astrodome during a game in the early 1970s. Jay lives in Knoxville, Tennessee, where he works in the medical device industry as a Quality professional.

Notes

1 As Leonard Koppett reminded us, official means “of the office”, not necessarily correct. See Koppett’s article, “BACKTALK: Official is a Relative Term, and It Always Will Be” New York Times, April 25, 1993, Section 8, page 9.

2 Bill James, “Introducing Project Scoresheet”, Baseball Analyst, Issue 8 (October 1983): 5-6.

3 David Smith, email to the author, November 2, 2018.

4 Jayson Stark, email to the author, July 11, 2019.

5 Smith, a professor in the University of Delaware’s Biology department, had never met Epstein, though Eddie was a Delaware graduate (with a Master’s degree in Economics), until Pete Palmer introduced them. A friendship began between Smith and Epstein, one further enhanced when Smith realized that Eddie’s Delaware advisor was one of Smith’s faculty friends.

6 Rick Vaughn, email to the author, September 18, 2018.

7 John Steadman, “Brown: Peerless among PR men, pride of O’s”, The Baltimore Sun, April 30, 2000.

8 Vaughn, email.

9 Steadman, “Brown: Peerless. . .”.

10 Vaughn, email.

11 David Smith, email to the author, February 10, 2020.

12 Smith, email.

13 Smith chose a 13-1 Orioles victory, unintentionally but completely appropriately. Visitors to the Retrosheet website today can view the training material for new volunteers at “Example Scoresheet,” Retrosheet.org, https://www.retrosheet.org/ex-sheet.htm.

14 Mike Dodd, “Ex-Oriole Jim Gentile lost $5,000 over error giving Roger Maris RBI crown,” USA Today, July 30, 2010.