Teenage Umpires of the Nineteenth Century

This article was written by Larry DeFillipo

This article was published in Spring 2024 Baseball Research Journal

Baseball tradition before the Civil War favored the selection of respected, senior members of the community as umpires, to interpret rules and resolve disputes between opponents typically grateful for their help. Interjecting themselves only now and then into the conduct of games, umpires were pampered; “given easy chairs, placed near home plate [and] provided with fans on hot days … their absolute comfort … uppermost in the minds of the players.”1 By the late-1860s, deference gave way to disrespect in the treatment of many umpires, as their role had evolved to passing judgment on nearly every pitch, often leaving one side or the other feeling wronged. The rise of professional baseball, and the subsequent popularity of gambling on the outcome of games, brought about more virulent reaction to umpiring decisions. With that, arbiters became younger. They needed to be athletic enough to move about the diamond during the action and better suited to handling physical confrontation.

Youth was clearly favored in the selection of National League umpires in its inaugural season, 1876. Based on Retrosheet’s game logs and biographical databases, the median age of the 61 umpires that officiated games that year was 25.2

At least three, and as many as four of those umpires were just 19 years old. Over the next two decades, another seven umpires under the age of 20 officiated major league games, as listed in Table 1. All toiled in either the NL or American Association. Neither the Players’ League nor the Union Association played a regular season game with a teenage umpire.

TEENS IN THE AMERICAN WORKPLACE

By present-day definition, 18- and 19-year-olds are “teenagers,” a term rarely used before the 1940s. But in the late 1800s, their place in society was vastly different than it is today. Secondary education was compulsory in few communities before 1900, so many children began working full time while in their early teens or younger. According to the 1870 US census, one in eight American children between the ages of 10 and 15 were members of the workforce. In 1880, 43% of white males between the ages of 10 and 19 were members of the workforce.3 Many nineteenth-century teenagers worked to help sustain family households and had done so since an early age.4

With fewer than one in 40 Americans aged 18–24 enrolled in institutions of higher learning by 1900, it was commonplace in many walks of life to see teenagers working alongside adults.5 Many luminaries of that age got their start as teens, like inventor Thomas Edison, who began working at age 12 and was a telegraph operator at 19; lawman Wyatt Earp, who transported cargo as an 18-year-old teamster; and author Mark Twain, who started his working life around age 12 and at 16 was a typesetter. The advent of professional baseball in the 1860s inspired many teenagers, but only a handful were lucky enough to be direct participants.

Roughly 7% of the ballplayers who played in the inaugural season of the National Association in 1871 were under the age of 20 (eight of 115). Even fewer of that age served as umpires during the NA’s five-year existence; seven or eight according to the Retrosheet database. So while the idea of a teenage major league umpire may seem ill-advised in the present day, to fans and ballplayers in the 1870s, their presence was infrequent but not unheard of.6

UMPIRE SELECTION AND DEMOGRAPHICS

During its inaugural seasons, the NL delegated responsibility to home teams for the selection of umpires, subject to approval of the visiting nine. Clubs relied heavily on umpires with no previous experience at the highest levels of the sport (e.g. in the defunct National Association), presumably because not enough experienced umpires or ballplayers were available. That opened the door for the NL’s three known teen umpires in 1876: John Morris, a Louisville amateur ballplayer; John Cross, a Rhode Island collegian; and Norman Fenno, a Boston Reds non-playing employee.

As was typical for NL umpires that year, Morris, Cross, and Fenno worked few games; four, one, and one, respectively. With teams cobbling together umpiring coverage from inexperienced hands, former NA ballplayers, and active ballplayers, two-thirds of 1876 NL umpires (41 of 61) worked no more than twice. All labored alone, as NL rules called for only one umpire to oversee games. Except for a few isolated trials with two-man crews, NL umpires worked solo until the 1898 season.7

The NL continued to allow home teams to select umpires for regular-season games in the 1877 and 1878 seasons, tweaking the process with regard to visiting team rights of refusal so as to reduce the likelihood of a biased umpire. During that time, only one umpire under the age of 20 worked an NL game, 18-year-old Bill Gleason, a member of a lower-level local professional team selected by the St. Louis Brown Stockings to work one of their games.

In 1879, NL President William Hulbert defined a pool of prospective umpires from which home teams, with concurrence of their opponents, could select arbiters for games. The average age of NL umpires rose to 27, with none under the age of 22. Not until 1881 did another umpire under the age of 20 work an NL game. In 1881, the Buffalo Bisons engaged a young player they’d released earlier that season, 19-year-old Dan Stearns, to umpire a three-game series for them.

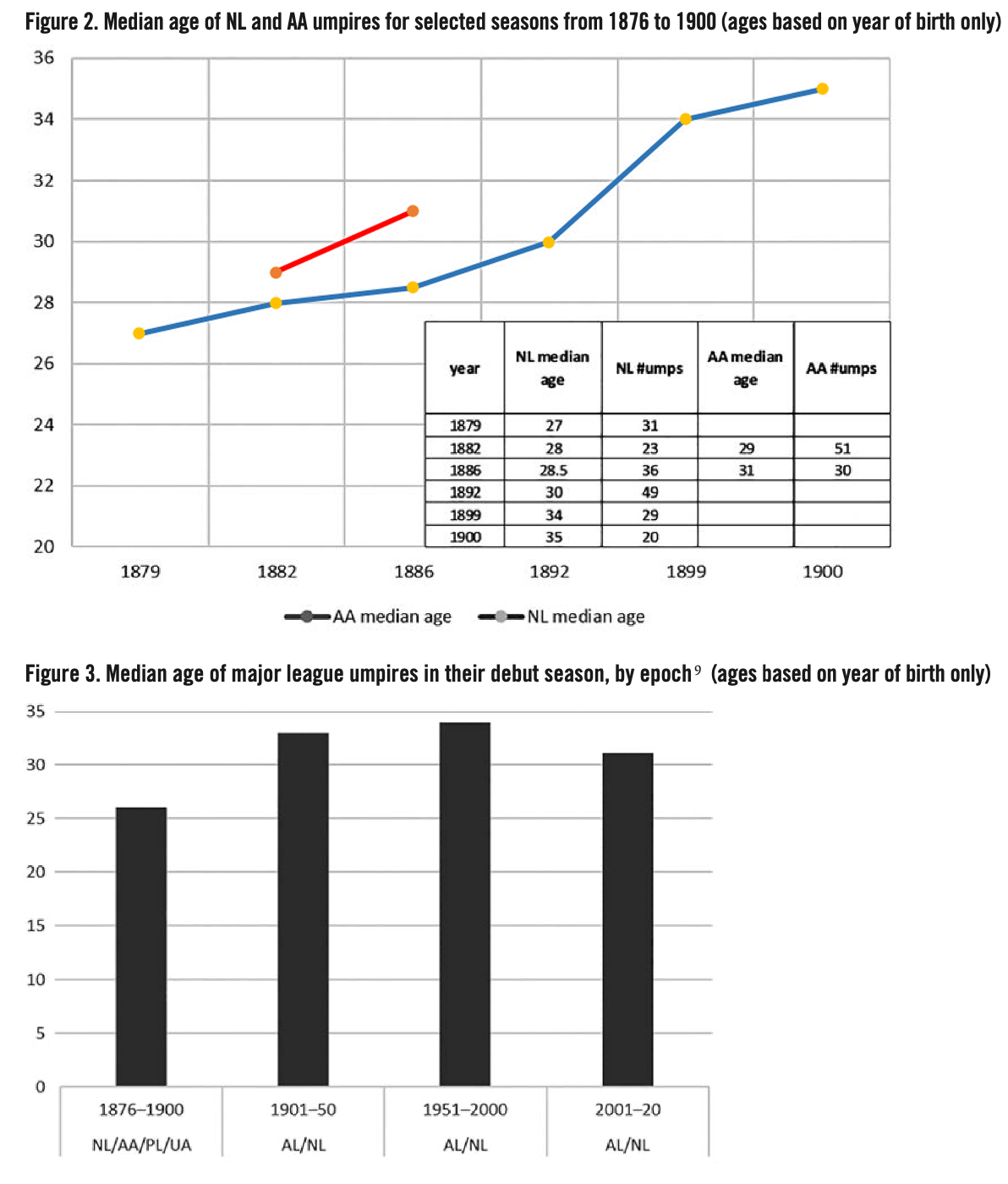

Shortly after the American Association opened for business in 1882, it went a step further than the NL had in centralizing league umpires. It maintained a cadre of umpires “hired, paid, and assigned to games by the league itself.”8 The NL followed suit in 1883. With their umpiring corps now league-controlled, the median age of major league umpires topped 28.

The median age of major league umpires continued to rise throughout the nineteenth century, reaching 35 in 1900. Yet across the four major leagues that were in operation between 1876 and 1900, the median age of new umpires was only 25, as shown in Figure 3. During the twentieth century, the NL and AL collectively favored new umpires who were more mature. From 1900 to 1950, median new umpire age across the two leagues was 33, rising to 34 in 1950–2000. In the first two decades of the twenty-first century that trend reversed, with the median umpire age over that period falling to 31.

Going back to 1879, when the NL first centralized the umpiring pool, when an umpire selected from Hulbert’s list became suddenly unavailable (due to illness or other circumstance), the home team bore the burden of finding a replacement. Otherwise it faced canceling scheduled games and losing gate receipts. In those situations, teams turned to players on their rosters who they could afford to have out of the lineup (typically pitchers unavailable that day or fielders nursing an injury), local amateurs (including college players), or club employees who worked behind the scenes (scorekeepers, ticket takers, etc).

Exactly how many replacement umpires were needed for major league games in the nineteenth century is unknown. Using the number of umpires who worked only one or two games in a season as approximating the number of replacement umpires, approximately 6% of major league games in 1879 were officiated by a replacement umpire. That number fell to as low as 1% in 1899, a year in which 95% of the league’s games were worked by two-man umpiring crews.

It was as a replacement that the next few teenage major league umpires came on the scene. In 1884, 19-year-old Brooklyn Grays pitcher Adonis Terry became the American Association’s first teenage umpire when he was inserted as an emergency replacement for an assigned umpire who’d taken ill. Two years later, Morgan Murphy was a local ballplayer inserted as an emergency replacement for an NL arbiter who’d come up sick. In 1887, 19-year-old Louisville pitcher Elton “Ice Box” Chamberlain worked an AA game, presumably as a replacement umpire. The next-to-last teenage major league umpire of the 1800s, 18-year-old Washington Nationals hurler Wilfred “Kid” Carsey, who also proved to be the youngest, subbed for an AWOL umpire in the AA’s final season, 1891.

Five years later, the last teenage major league umpire of the nineteenth century made his debut, but not as a replacement. Edward Conahan, a 19-year-old ump in a New Jersey semipro league, was hired into the umpiring corps by NL President Nick Young. Though he was heralded in his first few games, scathing newspaper critiques of his subsequent work triggered his dismissal after just 10 games. More than 80 years went by before the NL had another umpire under the age of 20, once again a temporary replacement. Conahan remains the one and only teenage umpire known to have been in the employ of a major league.

THEIR STORIES

In this section, the circumstances surrounding each teenage umpire’s first assignment are described, including what is known about how they came to be selected, game results, reviews from the press, and highlights from the balance of their days. Players are listed in the order in which they first appeared as major league umpires.

KNOWN TO BE TEENAGE UMPIRES

John Morris, 19 years exactly

Debuted 7/8/1876 (NL)

The first teenage major league umpire of the nineteenth century was Kentucky native John Stuart Morris. The son of a prominent Louisville businessman, Morris was a player with Fall City’s first organized baseball club, the amateur Louisville Base Ball Club.10 During the same summer that the United States celebrated its centennial, Morris umpired a quartet of games for Louisville of the newly formed National League. The first took place at Louisville Base Ball Park, on Morris’s 19th birthday, July 8, 1876. For reasons that the Louisville Courier-Journal called “inexplicable,” the Louisvilles and their opponents, the visiting Mutuals of Brooklyn, found experienced umpire Mike Walsh an unacceptable choice to umpire their contest and settled on Morris as an alternative.11 Louisville erased a four-run deficit in the bottom of the ninth to send the hard-fought game into extra innings, and Morris had to halt the action after 15 innings on account of darkness. The Courier-Journal called the game “unparalleled in the history of professional baseball-playing,” and singled out Morris for his hand in it. “We venture to say that no umpire ever gave more satisfaction to both sides in a long fifteen-inning game as he gave yesterday,” adding that Morris’s “judgment on balls and strikes was excellent, and also in points of base running. His decisions were quickly made and adhered to, and if his umpiring failed to satisfy the Mutuals we can only say that we have given them as good as we’ve got in the shop.”12

Morris umpired three more Louisville matches during the summer of 1876, each opposite the Chicago White Stockings. On August 5, he filled in for Charlie Hautz, who was upset that the NL office had reversed his decision to award the White Stockings a win over Louisville in a game Hautz had stopped two days earlier.13 Once again, Morris’s work drew raves. “Mr. Morris umpired the game intelligently and impartially. His decisions were correct in every instance, and, on the whole, he is as fine an umpire as there is in the West at the present day.”14 Later in life, Morris took his prowess as a baseball arbiter and applied it to the worlds of business and civic affairs. He served as the director of Louisville’s Commercial Club, a businessman’s society, and built a career working for the city of Louisville as an auditor for various municipal departments.15

John Cross, 19 years, 6 months, 3 days

Debuted 8/5/1876 (NL)

Shortly after completing their first homestand of the 1876 season, the Boston Red Stockings lost a match in Providence against the independent New Havens.16 The umpire for that late April game was John Alexander Cross, a Providence native and the regular catcher for Brown University’s nine.17 Two months later, the Red Stockings had Cross umpire an NL game with the Athletics of Philadelphia at Boston’s South End Grounds.The Athletics also invited a Boston amateur to help that day, John Bergh, a local catcher who filled in for their regular and backup catchers, who were both out with injuries. Struggling early, Bergh switched positions with the Athletics’ banged-up backup, Whitey Ritterson, who was playing center field. After Ritterson was struck in the wind pipe by a foul tip, Bergh returned behind the plate for the balance of the game, which Boston won.18

Two years later, Cross, who’d left Brown to help his father run the family textile mill, returned as an NL umpire. In the first of nine games he worked that year, on May 8, 1878, he called what may have been the first unassisted triple play in NL history. After catching a low line drive on a dead run, Providence center fielder Paul Hines raced to third base, where he put out two Boston Red Stockings baserunners; or possibly just one.19 Differing accounts of the play make it impossible to know for sure whether Hines retired all three himself, but without question it was Cross who rung them all up.20

Norman Fenno, 19 years, 4 months, 29 days

Debuted 8/7/1876 (NL)

The growth of professional baseball’s popularity in the late 1860s and early 1870s was accompanied by a voracious public appetite for statistics. Numbers allowed fans to compare the teams and players they might not be able to see with those they could, or imagined they could. For fans of the Boston Red Stockings, it was Norman Fenno, who compiled team statistics for public consumption.21 On August 7, 1876, Fenno, the heretofore “efficient and obliging official scorer of the Reds,” was drafted to umpire a contest between Boston and the visiting Athletics.22 The Red Stockings had employed several different umpires in recent home games, suggesting that with Fenno they were simply trying another. The Boston Globe mentioned that Fenno had made a few wrong calls in the game, won by Boston, 6–5. Referring to Beadle’s Dime Base-Ball Player, the bible of baseball rules edited by Henry Chadwick, the Globe went on to suggest, “A brief study of Chadwick would help matters amazingly with him.”23

Over the next few years, Fenno turned his facility with numbers into N.F. Fenno & Company, a banking and brokerage firm.24 In February 1879, Fenno went over to the dark side, disappearing with $16,000 in cash and securities borrowed from his customers.25 Newspaper reports presumed he had fled to Europe, but three years later, he turned up as an agent of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, living in Little Rock, Arkansas. Typhus took Fenno’s life at the age of 27.

Bill Gleason, 18 years, 10 months, 20 days

Debuted 10/1/1877 (NL)

Before he became a strong-armed, aggressive shortstop for the St. Louis Browns team that dominated the American Association in the 1880s, Bill Gleason played for the Minneapolis Browns of the League Alliance. A few weeks after the Browns had completed their 1877 season, Gleason umpired an October 1 NL contest between the Brown Stockings of St. Louis and Louisville.26 Gleason’s performance didn’t draw any comments from newspapers that covered that game, but multiple box scores misidentified him as a member of the St. Paul Red Caps, the rival of his Minneapolis squad.27 Before the month was out, two Grays who appeared in the game that Gleason umpired, left fielder George Hall and pitcher Jim Devlin, were expelled from the NL for their involvement in a scheme to fix games that came to be known as the Louisville Scandal.28 Fourteen years later, after Gleason had completed a major league career in which he collected over 900 hits, he umpired his second and last major league game, on Opening Day of what turned out to be the American Association’s final season.29

Dan Stearns, 19 years, 8 months, 12 days

Debuted 6/29/1881 (NL)

In 1880, Daniel Eckford Stearns became the first major league ballplayer born during the Civil War. A weak-hitting reserve with the Buffalo Bisons, he went unsigned until the first week of the 1881 season, when the Detroit Wolverines gave him a chance.30 Released a week later, Stearns joined the Buffalo fire department.31

At the end of June, Stearns took a break from wrestling a horse-drawn steam pumper to umpire a three-game series between the Bisons and the Boston Red Stockings. Buffalo downed Harry Wright’s squad in the opener, behind a 19-hit attack and the pitching of Pud Galvin. The Buffalo Commercial called the match “a roaring, red-hot game,” but chided Stearns for failing to reign in excessive kicking from both sides. “Never before have we seen such outrageous conduct towards a man chosen to act as referee in a game of ball,” claimed the Commercial, adding “Stearns was weak in not appreciating the dignity of the position he occupied.”32 After the next game, the Buffalo Morning Express gave Stearns a D for expertise but an A for effort. Stearns “tried hard to treat one side as justly as the other,” the Express reported, suggesting “the only blame that Buffalonians could offer to his work yesterday was that he did not increase the League treasury” by fining a pair of ill-mannered Red Stockings.33 For reasons unexplained, Boston objected to Stearns umpiring the finale, but relented.34 In a major league career spent with five teams over parts of seven seasons in the NL and the American Association, Stearns was perhaps best known for making the final out for the Cincinnati Red Stockings in Louisville hurler Tony Mullane’s no-hitter on September 11, 1882, the first in Association history.35

Adonis Terry, 19 years, 11 months, 26 days

Debuted 8/2/1884 (AA)

William H. Terry, later known as Adonis, was the American Association’s first teenage umpire. An 18-year-old pitching prodigy for the 1883 Brooklyns of the Interstate Association (16–9 with a 1.38 ERA) Terry had a dismal 10–16 record on August 1 of the following year, having lost six of his last seven starts for Brooklyn.36 The next day, Brooklyn manager George Taylor tabbed Terry to fill in for scheduled umpire John Valentine, who’d taken ill before Brooklyn’s home game with the Baltimore Orioles at Washington Park. The Brooklyn Eagle reported that Terry, five days away from his 20th birthday, umpired the game, won by Brooklyn in front of 3,000 “gratified spectators,” “with thorough impartiality.”37 The day after his 20th birthday, Terry umpired for a second and final time that season. He umpired 10 times during a 14-year major league career in which he won 197 regular season games and three World Series games.38 Hired as an NL umpire in 1900, Terry worked 39 games that year, including a July 12 no-hitter thrown by Cincinnati’s Noodles Hahn against the Philadelphia Phillies.39

Morgan Murphy, 19 years, 7 months, 1 day

Debuted 9/15/1886 (NL)

Morgan Murphy burst onto the Boston baseball scene in the spring of 1886 as a catcher for the Boston Blues of the New England League. In late-August, the Boston Globe called Murphy “the pluckiest catcher in the New England League,” describing his work behind the plate as “beautiful,” “unsurpassed,” and “magnificent, and at times simply superb.”40 Two weeks after that assessment, Murphy umpired an NL tilt at Boston’s South End Grounds between the Red Stockings and the visiting Philadelphia Phillies, subbing for Chick Fulmer, a member of the league’s umpiring corps too sick to officiate. Boston won the game, 5–3, with pitcher Bill Stemmyer holding off a Phillies rally in the bottom of the ninth. The game ended as would Ernest Thayer’s as-yet-unwritten classic; with Casey (in this case Stemmyer’s opposite number, Dan Casey) at the bat.

Unlike the nameless ump that eternally draws the ire of Thayer’s imaginary patrons, no threats on Murphy’s life nor claims of trickery were reported during the real Casey’s final at the bat, which ended of course with a strikeout. According to the Globe, Murphy did well throughout the contest. “His judgment on balls and strikes was good, and of the two questionable decisions he made … neither affected the score.”41 Four years later, Murphy reached the major leagues as a player, backstopping for the Boston Brotherhood Club of the Players League.42 Over an 11-year major league career, Murphy umpired five more games and became one of only six ballplayers to play in the Players League, National League, American Association, and American League.

Ice Box Chamberlain, 19 years, 10 months, 20 days

Debuted 9/25/1887 (AA)

Nicknamed “Ice Box” for his ability to stay calm under pressure, Elton Chamberlain was one of a small group of nineteenth-century hurlers known to have pitched with either hand.43 In 1887, the 19-year-old Chamberlain, along with 22-year-old southpaw Toad Ramsey and veteran Guy Hecker, gave the American Association Louisvilles a formidable pitching staff expected to challenge the two-time defending pennant winner and reigning World Series champion, the St. Louis Browns.

As Louisville dropped out of the pennant race in late August, they fell into turmoil. Ramsey was suspended for thuggish conduct and Chamberlain accused the widely unpopular Hecker of threatening “to freeze him out of the club.”44 The Louisville Courier-Journal reported a “mutiny brewing,” with everyone on the team wanting Hecker gone.45 In Ramsey’s second start back after cooling his heels for a week, he faced the last-place Cleveland club at Louisville’s Eclipse Park, with Hecker at first and Chamberlain doing the umpiring.46 Three thousand “heartily disgusted” fans saw Louisville “succumb to the Cleveland tailenders” by a 14–4 score. Ed, as the Courier-Journal called him, “umpired satisfactorily.”47 By all accounts, Hecker and Chamberlain had no altercations in the game nor during the rest of their time playing for Louisville. A winner of 157 major league games in 10 seasons, Chamberlain found his way into NL record books for two pitching performances at the tail end of his career. On September 23, 1893, he authored a darkness-shortened no-hitter against the Boston Beaneaters. Eight months later, Boston second baseman Bobby Lowe clubbed four home runs off Chamberlain, becoming the first major leaguer to do so in a game.

Kid Carsey, 18 years, 10 months, 17 days

Debuted 9/7/1891 (AA)

The youngest nineteenth-century major league umpire was Wilfred “Kid” Carsey, a rookie pitcher for the 1891 Washington Nationals. No American Association pitcher lost more games or threw more wild pitches that season than Carsey did. His 37 defeats for the last-place Nationals were 10 more than the second-place finisher, Phil Knell of the Columbus Buckeyes.

On Labor Day 1891, the Nationals and Buckeyes squared off at Washington’s Boundary Field for a doubleheader. At game time for the morning opener, scheduled umpire John Kerins was absent, his whereabouts unknown. Washington manager Dan Shannon agreed with his Columbus counterpart, Gus Schmelz, to form a two-man replacement umpiring crew with one player from each team.48 Carsey, six weeks shy of his 19th birthday, was chosen to umpire from behind the plate, with Knell selected to umpire from the field. The responsibility for calling balls and strikes rested not with Carsey, but instead alternated between the two; Carsey handled that duty when his teammates came to bat, and Knell did the same when Columbus was on offense.

Washington elected to bat first, as Association rules then allowed home teams to do, with Carsey overseeing the offerings of hurler Hank Gastright. When Nationals pitcher Martin Duke first took the field, Knell “waltzed up to the rubber and essayed to call balls and strikes.”49 In the bottom of the second, Columbus put together an 11-run rally, during which Kerins, the day’s scheduled umpire, finally appeared. After the third out, he relieved the two substitute umpires of their responsibilities.

According to a play-by-play in the Washington Evening Star, Carsey entered the game in the eighth inning, grounding out as a pinch-hitter.50 Thus, he both officiated and played in the same game; a feat rare and maybe even one of a kind. Over the next ten years, Carsey appeared in 268 major leagues games as a player and four as an umpire. Never again did he do both in the same contest.

Ed Conahan, 19 years, 3 months, 3 days

Debuted 8/8/1896 (NL)

Conahan took to umpiring early, working amateur baseball games in his hometown of Chester, Pennsylvania at the tender age of 14.51 By 1896, the 19-year-old had moved up to umpiring in the independent South Jersey League.52 In early August of that year, he earned an umpiring appointment from NL president Nick Young.53 Conahan debuted on August 8, officiating a contest at Philadelphia’s Ball Park (later known as Baker Bowl) between the hometown Phillies and the Boston Beaneaters.54 In its retelling of the Phillies win in the midst of an oppressive heat wave, the Philadelphia Inquirer dubbed Conahan’s efforts “the bright particular feature of the game,55 adding that “he’s got a great voice and renders his decisions promptly and intelligibly—a boon which will be readily appreciated by the great army of ball goers.”56 After Conahan’s next umpiring assignment six days later, the Inquirer said, “The new umpire, Conahan, unearthed by Nick Young in the wilds of Jersey,” was “a peach.” “He’s a nice accommodating lad too. He runs around and picks up the catchers’ masks for them and with deferential bow delivers himself: ‘Illustrious Sir, allow me.’”57

Glowing with praise for Conahan’s first four games as an umpire, reviews soon turned sharply negative. Multiple accounts describe Conahan’s performance in his fifth game, on August 19, as subpar.58 Things snowballed from there. Following a doubleheader split the next day between the Phillies and the Louisville Colonels, the Philadelphia Times called Conahan’s umpiring “of the rankest kind,” adding that his decisions were so confounding they “would make an angel forget his vows.”59 The Times continued its condemnations the next day, calling Conahan’s efforts in a Phillies win “yellow work.”60 The Inquirer called for Conahan’s dismissal.61 A twin bill on August 22 between the Phillies and St. Louis Browns proved Conahan’s last games as a major league umpire. Once again, the Times brutalized Conahan, calling his work “slovenly,” and the “the worst ever seen on local grounds.” The Inquirer reported that Conahan “gave a weird exhibition all through,” with one call so rotten it triggered an argument that got St. Louis’s umpire-baiting shortstop Monte Cross unfairly ejected.62

Three days later, Conahan was fired.63 He went back to umpiring amateur games in Chester and eight years later was umpiring professional baseball in the independent Pennsylvania League, New York State League, and Eastern League. He signed on as an American League umpire for the 1906 season, but was let go before the start of the regular season.64 Conahan later umpired in the Western League, the minor league American Association, the International League, the Southern Association, and the Tri-State League.65

MIGHT-HAVE-BEEN TEENS

Two umpires in the National League’s inaugural season are identified by Retrosheet as born in Cincinnati on an unknown date in 1856; William E. Walker and Enoch Clifford Megrue. Research suggests they were on either side of 20 when they first umpired major league games in the summer of 1876.

The 1900 US Census lists Walker, at that time still a Cincinnati resident, as born in January 1856. Age data in census rolls of that era can be faulty, but Walker’s entry suggests that he turned 20 months before umpiring his first NL game. A newspaper account of Megrue’s death in September of 1893 claimed he was 35-years-old, implying he might have been as young as 17 when he first officiated.66 Walker and Megrue crossed paths on a baseball diamond, both as players and as umpires, with Walker’s early success at umpiring opening a door for Megrue. In 1876, William E. Walker was both manager and substitute for the amateur Ludlow Base Ball Club of Ludlow, Kentucky.67 Located across the Ohio River from Cincinnati, Ludlow frequently played other amateur teams in the Queen City. One of those was the Cincinnati Junior Reds, whose left fielder was Enoch Clifford Megrue, a son of Cincinnati’s fire chief.68 Walker debuted as an NL arbiter in a match between the Boston Red Stockings and the Reds on June 24. Apparently pleased with his work, the Reds called Walker back to umpire a mid-July contest, and five of the Reds next six home games as well. But on August 10, Walker wasn’t available; he was working a game in Louisville. Replacing Walker for the contest at Cincinnati’s Avenue Grounds was Megrue. Accounts of the game with the Chicago White Stockings, in which Al Spalding shut out Cincinnati, were silent on Megrue’s performance.69 Walker went on to umpire a total of 29 NL games across three seasons, and after his baseball days, became a theatrical publicist.70

Megrue’s future exploits were decidedly less entertaining. He inherited a substantial sum of money after his father’s death in 1881, but squandered it over the next decade. Reduced to living on the charity of relatives, he died of alcoholism while in his 30s.71

A CASE OF MISTAKEN IDENTITY

In addition to the youngsters described above, Retro-sheet’s database identifies one other teenage major league arbiter in the nineteenth century: Michael Joseph Sullivan, a pitcher with the NL Washington Nationals, is listed as having umpired a game on October 2, 1889, several weeks before his 19th birthday. That game, held at Chicago’s West Side Park between the Nationals and the White Stockings, was in fact umpired by another Sullivan: 33-year-old Chicago-native David Sullivan. An umpire for the Union Association in 1884 and the National League in 1885, David was filling in for league umpire Pat Powers that day, according to the Chicago Tribune.72 A summary published in the Chicago Inter-Ocean also names David as the umpire for that game.73

POSTSCRIPT

Of the hundreds of major league umpires who’ve worked a regular season game since the turn of the twentieth century, only one is known to have been a teenager: 19-year-old Roger Dierking, an emergency replacement during the one-day umpires strike in 1978.74 An airline employee and part-time college umpire in Chula Vista, California, he was two months shy of his 20th birthday when he umpired at first base for a game between the San Diego Padres and the visiting New York Mets on August 25, 1978, at Jack Murphy Stadium.

In 2018, the average major league umpire was 46 years old, with 13 years of professional experience. In reporting the results of a Boston University study on the correlation between umpire age and accuracy in calling balls and strikes during that season, Fanbuzz noted that the 10 most accurate umpires were over a decade younger than average, with a decade less experience.75 Eye-opening as that finding may be, the inevitable switch to “robo umps” will make that particular distinction irrelevant in the not-too-distant future.

LARRY DeFILLIPO is a retired aerospace engineer who lives in Kennewick, Washington with his wife Kelly. A SABR member since the late 1990s, his work has been published in The National Pastime and “Yankee Stadium 1923-2008: America’s First Modern Ballpark,” and presented at the 2023 Fred Ivor-Campbell 19th Century Baseball Conference. He’s also authored biographies of several prominent baseball figures and stories about a variety of important nineteenth-century games, for SABR’s Biography and Games Projects, respectively.

Notes

1 Peter Morris, A Game of Inches (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006), 22.

2 Median age value excludes a half-dozen umpires whose dates of birth are unknown. Retrosheet’s database includes 549 individuals who debuted as umpires in one of the four major leagues that were in operation during the nineteenth century (National League, American Association, Union Association and Players’ League). Of that group, 7% (36) have unknown dates of birth, with only the year of birth known for another 15% (80). https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/index.html#Umpires

3 Robert Whaples, “Child Labor in the United States,” Economic History, https://eh.net/encyclopedia/child-labor-in-the-united-states/, accessed December 22, 2023.

4 Lauren Bauer, Patrick Liu, Emily Moss, Ryan Nunn and Jay Shambaugh, “All School and No Work Becoming the Norm for American Teens,” the Hamilton Project, July 2, 2019, All School and No Work Becoming the Norm for American Teens.

5 Thomas D. Snyder, ed., 120 Years of American Education: A Statistical Portrait (Washington: U.S. Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics, 1993), 76, https://nces.ed.gov/pubs93/93442.pdf

6 Richard J. Bonnie, Clare Stroud, and Heather Breiner, eds., Investing in the Health and Well-Being of Young Adults (Washington: National Academies Press, 2015), 36, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/ NBK284782/, accessed August 25, 2023. As a result of facing profound physical, cognitive, and emotional changes in an ever-changing world, adolescents, according to the National Institute of Health, “tend to be strongly oriented toward and sensitive to peers, responsive to their immediate environments, limited in self-control, and disinclined to focus on long term consequences, all of which can lead to compromised decision-making skills in emotionally charged situations.” Behaviors that are the very opposite of those desirable in a professional umpire.

7 Morris, A Game of Inches, 254.

8 Larry R. Gerlach and Bill Nowlin, The SABR Book of Umpires and Umpiring (Phoenix: SABR, 2017), 161.

9. The number of umpires debuting in each epoch for whom their year of birth is known was 513 in 1876–1900; 246 in 1901–50; 354 in 1951–2000; and 92 in 2001–20.

10 “Louisville Base Ball Club,” Protoball, https://protoball.org/Louisville_Base_Ball_Club, accessed August 28, 2023.

11 “Pull, Duck; Pull, Devil!” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 9, 1876, 1. Walsh, who had worked a half-dozen National Association games the year before and nearly 20 to that point of the 1876 NL season, had umpired two games between the Grays and Mutuals earlier that week.

12 “Pull, Duck; Pull, Devil!”

13 “Who Says We’re Pie?” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 6, 1876, 1; Brian Flaspohler, “Charlie Hautz,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Charlie-Hautz/; “Base Ball,” Evansville (Indiana) Journal, August 4, 1876, 1.

14 “Who Says We’re Pie?”

15 “Water Company Auditor, 63, Dies.” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 27, 1921, 3.

16 “New Haven vs. Boston,” New York Clipper, May 6, 1876, 45.

17 See, for example, “Brown vs. Amherst,” New York Clipper, June 26, 1875, 101; and “Yale vs. Brown,” New York Clipper, June 3, 1876, 75.

18 Two days later, when Ritterson’s hands gave out late in a contest with the Hartford Dark Blues, there was nobody willing or able to catch, forcing Lon Knight of the Athletics to pitch the last inning without a catcher. Larry DeFillipo, “August 10, 1876: Short-handed Athletics borrow substitute from Mutuals, as both teams careen toward expulsion,” SABR Games Project; “The Bostons Vanquish the Athletics Again,” Boston Globe, August 7, 1876, 2c.

19 “Ball Games,” Boston Globe, May 9, 1878, 1; Kathy Torres, “May 8, 1878: Three in one? Paul Hines’ unassisted triple play,” SABR Games Project.

20 Cross’s officiating performance earned him an invitation to become a regular NL umpire for the 1879 and 1880 seasons, but he declined, preferring to run the family mill instead. “Resignation of a League Umpire,” Providence Evening Bulletin, March 14, 1881, 1; “1878-NON,” Providence Journal, May 18, 1942, 8.

21 Following the 1873 National Association season, Fenno provided the Boston Globe with 28 “interesting” rows that described each player’s contributions to the two-time defending champions’ 43–16 season. “Interesting Items—The Bostons’ Record for 1873,” Boston Globe, November 10, 1873, 5.

22 “Record of the Champions,” Boston Post, November 16, 1874, 3.

23 “Base Ball,” Boston Globe, August 8, 1876, 1.

24 “N.F. Fenno & Co,” Boston Golden Rule, December 11, 1878, 3.

25 “Eastern Massachusetts,” Springfield Republican, February 6, 1879, 7.

26 “Base Ball,” Minneapolis Tribune, September 5, 1877, 2.

27 “The Game,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 2, 1877, 7; “Base Ball,” Louisville Courier-Journal, October 2, 1877, 1.

28 “Why the Men Were Expelled,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 31, 1877, 3. For more information on the fixing scandal, see Daniel E. Ginsburg, “The Louisville Scandal” in Road Trips: A Trunkload of Great Articles From Two Decades of Convention Journals (Cleveland: SABR, 2004), 71–72.

29 “The Base-Ball Season Opened,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 9, 1891, 9. The contest featured the St. Louis Browns hosting Cincinnati, a short-lived team that would soon be dubbed Kelly’s Killers. In that game, the team’s namesake, captain and catcher Mike “King” Kelly, grew infuriated over four walks Gleason granted to Browns batters. Kelly tore off his glove and stormed off the field. Gleason allowed the petulant Kelly to bat in the next half-inning but barred him from returning to the field.

30 “Today’s Game,” Buffalo News, May 5, 1881, 9.

31 “Sporting Notes,” Buffalo Commercial, June 9, 1881, 3.

32 “Sporting News,” Buffalo Commercial, June 30, 1881, 3.

33 “Ill-Mannered Bostons,” Buffalo Express, July 1, 1881, 4. The Boston players thought deserving of fines were Jack Burdock and Pat Deasley.

34 “Sporting News,” Buffalo News, July 4, 1881, 1.

35 Charles F. Faber, “Dan Stearns,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/dan-stearns/

36 Based on a game log of Terry’s pitching appearances compiled by the author.

37 “The Home Nine Wins,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 3, 1884, 2.

38 Larry DeFillipo, “Adonis Terry,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/adonis-terry/

39 “Hahn,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 13, 1900, 4.

40 “Bunched Hits,” Boston Globe, August 31, 1886, 2; “If ‘Murph’ Had Been Well?” Boston Globe, August 27, 1886, 3; “The Lynns Get Left,” Boston Globe, August 25, 1886, 5.

41 “Willie is a Daisy,” Boston Globe, September 16, 1886, 5.

42 The others were Bill Hallman, Billy Hoy, Gus Weyhing, Hugh Duffy, and Lave Cross.

43 Other ambidextrous pitchers of the nineteenth century included Larry Corcoran and George Wheeler, and possibly Tod Brynan. Charles F. Faber, “Ice Box Chamberlain,” SABR, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/ice-box-chamberlain/

44 “Ramsey Suspended,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 28, 1887, 5; “Hecker Must Go,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 19, 1887, 3.

45 “Hecker Must Go.”

46 “Six to Four,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 23, 1887, 3.

47 “King Tom No More,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 26, 1887, 2.

48 “Lost By Poor Fielding,” Washington Evening Star, September 7, 1891, 3.

49 “Lost By Poor Fielding.”

50 “Lost By Poor Fielding.” Carsey was hitting for pitcher Ed Cassian, who’d relieved Duke in the disastrous second inning. The accompanying box score doesn’t show Carsey batting, but it was common for box scores of that era to omit statistics for pinch-hitters.

51 “Houston Wins from Upland,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 2, 1891, 3.

52 See, for example, “Millville, 7; Bridgeton 6,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 24, 1896, 5.

53 “The Beaneaters Downed with Much Trouble,” Wilkes-Barre Sunday News, August 9, 1896, 1.

54 “More Like It,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 9, 1896, 8.

55 “More Like It”

56 “More Like It.” The front page of the next day’s Philadelphia Times listed nine heat-related deaths. The heat wave, which affected the eastern half of the US, lasted 10 days and took the lives of an estimated 1,500 people. “Heat Kills Nine More,” Philadelphia Times, August 9, 1896, 1.

57 “Couldn’t Hit Gumbert,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 15, 1896, 5.

58 “More Like the Real Stuff,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 20, 1896, 5; “Between the Innings,” Philadelphia Times, August 20, 1896, 8.

59 “We Won and Lost to the Colonels,” Philadelphia Times, August 21, 1896, 8.

60 “Louisville Was Again a Victim,” Philadelphia Times, August 22, 1896, 8.

61 “Passed Balls,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 22, 1896, 5.

62 “Passed Balls,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 23, 1896, 8.

63 “Conahan Gets the Dinky-Dink,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 26, 1896, 5.

64 “Gossip for the Fans,” Plainfield (New Jersey) Courier-News, November 20, 1905, 5; “Conahan Released,” Scranton Times-Tribune, March 5, 1906, 3.

65 “Conahan, Veteran Umpire, Dies After Operation,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 14, 1929, 3.

66 “In Bed,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 12, 1893: 4.

67 “Reorganization of the Ludlows,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 17, 1876, 1.

68 See, for example, “Junior Reds vs. Ludlow,” New York Clipper, June 10, 1876, 85; “In Bed,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 12, 1893, 4.

69 “Six to Nothing,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 11, 1876, 5; “The Chicagos at Cincinnati,” Chicago Tribune, August 11, 1876: 5.

70 “’Smiley’ Walker Stricken,” Cincinnati Enquirer, February 8, 1909, 8. Going by the name of “Smiley,” Walker’s most renowned client was Fanny Davenport, an actress who favored roles created for future silent film star Sarah Bernhardt.

71 “Dizzy from Drink,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 29, 1891, 4; “In Bed,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 12, 1893, 4.

72 Powers had worked the two previous games of the series. “Their Last Encounter,” Chicago Tribune, October 3, 1889, 6.

73 Box scores in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat and Cincinnati Enquirer further support that it was David handling the umpiring chores. Each listed the game’s umpire as “D. Sullivan.” “Hard Knocks for Krock,” Chicago Inter-Ocean, October 3, 1889, 6; “Chicagos, 9; Washingtons, 7,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 3, 1889, 8; “Very Poor Game,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 3, 1889, 2.

74 Chula Vista (California) Star-News, May 5, 1974, B-1; Dave Distel, “Umpires Missing, So Is Hitting by Padres,” Los Angeles Times, August 26, 1978, III-1.

75 John Duffley, “Study Finds that Old Men with Experience are Actually the Worst MLB Umpires,” Fanbuzz, July 7, 2022, https://fanbuzz.com/mlb/worst-mlb-umpires-study/