Testing the Koufax Curse: How 18 Jewish Pitchers, 18 Jewish Hitters, and Rod Carew Performed on Yom Kippur

This article was written by Howard M. Wasserman

This article was published in Fall 2020 Baseball Research Journal

Yom Kippur — the Day of Atonement on which Jews fast, seek forgiveness from God and other people, and rehearse their deaths1 — occupies an iconic space in the annals of baseball and American Jewry. Jewish-American fans regularly contemplate and debate whether Jewish players will and should play on the holy day.2

Yom Kippur — the Day of Atonement on which Jews fast, seek forgiveness from God and other people, and rehearse their deaths1 — occupies an iconic space in the annals of baseball and American Jewry. Jewish-American fans regularly contemplate and debate whether Jewish players will and should play on the holy day.2

Yom Kippur in the Hebrew Year 5780 (sundown Tuesday, October 8, 2019, through sundown Wednesday, October 9, 2019) offered a unique exhibit in that debate. Three Major League Division Series games began within that 24-hour period. One team in each game featured a Jewish player as star or significant contributor. Each Jewish player appeared in the game. Each team lost.

On Tuesday evening (during Kol Nidre, the beginning of the holy day), the Houston Astros lost Game Four of their best-of-five American League Division Series to the Tampa Bay Rays. Alex Bregman, the Astros star third baseman, played and went 1-for-4. But the Astros allowed three first-inning runs and never were in the game. The loss forced a deciding fifth game, played two days later following an off-day on Yom Kippur.

At 5:02 pm EDT Wednesday (around the start of Neilah, the service that closes the holy day), the Atlanta Braves began a deciding Game Five of their NLDS, surrendering a postseason record 10 first-inning runs in a 13-1 loss. Braves left-hander Max Fried did not start but was pressed into first-inning relief; he surrendered four earned runs in less than two innings of work.

At 5:38 pm PDT Wednesday, before the holy day ended with the blowing of the shofar and breaking of fasts with bagels and kugel, the Los Angeles Dodgers began Game Five of their NLDS against eventual World Series champion Washington Nationals. Dodgers outfielder Joc Pederson started and hit what appeared to be a first-inning homer, although video review showed the ball traveled through a hole in — rather than over — the fence for a ground-rule double. Pederson scored on a subsequent first-inning homer, so no harm/no foul, except for his statistics. The Dodgers surrendered a two-run lead in the eighth inning and allowed four in the 10th to lose the game and the series.

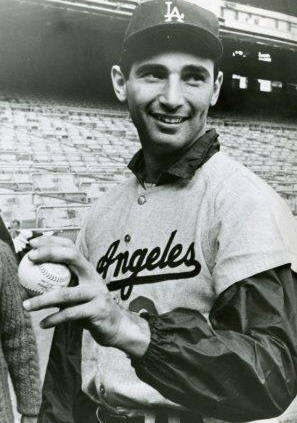

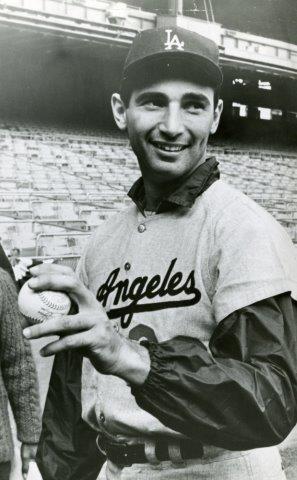

Journalist Armin Rosen labeled this the “Koufax Curse.”3 It is the curse of the Jewish player who plays on Yom Kippur, rather than following in the footsteps of Dodgers Hall of Fame pitcher Sandy Koufax, who did not pitch Game One of the 1965 World Series on Yom Kippur 5726.4 Koufax is not alone in his actions (or inactions) among Jewish players. Hank Greenberg skipped a Yom Kippur game during a pennant race in September 1934.5 Shawn Green and Kevin Youkilis earned praise for skipping multiple Yom Kippur games during their careers. But the practice, and thus the curse, remain wedded to Koufax — whether because of his special greatness, that he missed a World Series game, or recency bias.6

Rosen acknowledges that “it’s a theological stretch to claim that there’s some kind of Koufax curse at work whereby Hashem punishes teams whose star Jewish players don’t sit out on Yom Kippur. That would be an absurd and completely nondisprovable thing to assert. Why would Yom Kippur observance be the determinative factor in a baseball game? Surely Hashem isn’t that petty.”7

But correlation does not require causation. There might be a Koufax Curse in the sense of diminished performance by Jewish players and their teams — whether the cause be divine will, Jewish guilt, regression to the mean, or the nature of baseball as a game of failure.

If there is a Koufax Curse, it finds fertile haunting ground in Jewish baseball’s new gilten alter (golden age).8 Fifteen Jewish players spent all or part of 2019 in the major leagues.9 Their ranks included several regulars who contributed significantly to their teams, and an All-Star and American League MVP runner-up in Alex Bregman. Thirteen spent all or part of the COVID-19-shortened 2020 season in the majors, including five regulars and a star starting pitcher. The last four World Series have featured at least one Jewish player. The 2017 (Bregman and Pederson), 2018 (Pederson and Ian Kinsler of the Red Sox), and 2020 Series (Pederson and Ryan Sherriff of the Rays) featured one Jewish player on each team, including the first game in which each team started a Jewish player and the first Series (2017) in which multiple Jewish players homered.10 Pederson and Bregman have each hit five World Series home runs, most among Jewish players. The two also staged an epic one-on-one contest in the first round of the 2019 Home Run Derby.

This renewal follows a fallow period from the late 1970s to early 1990s, during which the few Jewish players were non-starters.11 Green arguably launched the renaissance when he emerged as a star outfielder for the Toronto Blue Jays in 1995, the best Jewish player since pitcher Ken Holtzman in the 1970s; the attention on Green included invitations to Bar Mitzvahs in the Toronto area.12 Numerous Jewish stars and everyday players have followed in the past three decades.

A legacy Jewish press has always covered Jewish athletes wherever they could be found.13 Jewish-issues publications, such as The Forward and Tablet Magazine, publish stories on Jewish baseball players.14 But new sites such as the online Jewish Baseball News, the Jewish Baseball Museum, and the tongue-in-cheek generalist site Jew or Not Jew, which includes a section on athletes, have arisen to report on this emerging topic.15 The result is a perfect confluence — many Jewish baseball players to talk about and many outlets in which to talk about them. And an annual topic remains what Jewish baseball players do or do not do — and should or should not do — on Yom Kippur.16

Rosen is correct that Hashem is not so petty as to smite Jewish players with poor performance if they play on the holy day.17 But a correlative question remains: How do Jewish players, and the teams that employ them, perform when they play or choose not to play on Yom Kippur?

This article identifies 36 Jewish players — 18 nonpitchers and 18 pitchers — since 1966/5727, the year after Koufax sat during the World Series. Through box scores from Yom Kippur games for each season of their careers, it explores whether they played on any part of the holy day and charts how they and their teams performed. It conducts the same analysis for Rod Carew, the Hall of Famer who is not Jewish but enjoys a unique familial and cultural connection to Judaism-in-baseball. From this, we can draw conclusions about whether players or teams are haunted by the Koufax Curse. And whether Yom Kippur 5780 was an anomaly or reflects a broader historical correlation since 1966.

1. Identifying the Koufax Curse

A. The Players

Koufax’s 1965 non-start stands as the watershed event in Jewish baseball.18 This study thus begins in 1966 (Yom Kippur 5727) — the beginning point for any “curse” upon Jewish players who would fail to follow Koufax’s lead.

Given the importance of the number 18 in Judaism as the numerical representation of life, that number frames the study.19 I identify 18 nonpitchers and 18 pitchers since 1966 with at least one Jewish parent and who self-identified to some degree with their Jewish heritage.20 Players are listed in chronological order from their debuts. (As noted, the 1980s were a fallow period for star Jewish players, leaving a bit of gap between starters of the 1970s and the revival in the 1990s and early 2000s.)

Nonpitchers

- Mike Epstein: 1B: 1966-74 (Bal; Was;21 Oak; Tex; Cal)

- Ron Blomberg: 1B/OF/DH: 1969-78: (NYY, ChW)

- Bob Melvin: C: 1985-94 (Det; SF; Bal; KC; Bos; NYY; ChW)

- Ruben Amaro, Jr.: OF: 1991-98 (Cal; Phi; Cle)

- Brad Ausmus: C: 1993-2010: (SD; Det; Hou; LAD)

- Shawn Green: OF: 1993-2007 (Tor; LAD; Ari; NYM)

- Mike Lieberthal: C: 1994-2007 (Phi; LAD)

- Gabe Kapler: OF: 1998-2010 (Det; Tex; Col; Bos; Mil; Tam)

- Kevin Youkilis: 1B/3B: 2004-13 (Bos; ChW; NYY)

- Ian Kinsler: 2B: 2006-2019 (Tex; Det; LAA; Bos; SD)

- Sam Fuld: OF: 2007-15 (ChC; Tam; Oak; Min)

- Ryan Braun: OF: 2007-Present (Mil)

- Ike Davis: 1B: 2010-16 (NYM; Pit; Oak; NYY)

- Danny Valencia: 3B/1B/OF: 2010-18 (Min; Bos; Bal; KC; Tor; Oak; Sea)

- Kevin Pillar: OF: 2013-Present (Tor; SF; Bos; Col)

- Joc Pederson: OF: 2014-Present (LAD)

- Alex Bregman: 3d: 2016-Present (Hou)

- Rowdy Tellez: 1B/DH: 2018-Present (Tor)

Among nonpitchers, five remain active as everyday players. Most enjoyed at least a few seasons as regular or semi-regular players, appearing in 110 or more games with 400 or more plate appearances. Several enjoyed (or continue to enjoy) lengthy careers.

The best in the group are Green (two-time All Star, third in home runs by a Jewish player); Youkilis (three-time All Star, Gold Glove first baseman, key player on two championship teams); Kinsler (four-time All Star, two-time Gold Glove infielder, played in three World Series); and Braun (six-time All Star, 2007 Rookie of the Year, 2011 MVP, career leader in home runs by a Jewish player with 35222).

None is likely to make the Hall of Fame; Green fell off the ballot after receiving two votes in his first year of eligibility, and Youkilis received no votes in his first year of eligibility in 2019.23 Epstein hit at least 19 home runs in four consecutive seasons, including as the starting first baseman for the 1972 World Series champion A’s. Pederson has topped 24 homers four times, including 36 in 2019, and has hit five World Series home runs. Blomberg claims the historic achievement of being the first designated hitter, drawing a first-inning walk on Opening Day 1973. Bregman could become the best of the group — at 26, he has played five seasons, made two All-Star teams, finished second in the 2019 MVP balloting, and hit five World Series home runs.

Pitchers

- Ken Holtzman: (S) 1965-79 (ChC; Oak; Bal; NYY)

- Dave Roberts (S) 1969-81 (SD; Hou; Det; ChC; SF; Pit; Sea; NYM)

- Steve Stone: (S) 1971-81 (SF; ChW; ChC; Bal)

- Ross Baumgarten (S) 1978-82 (ChW; Pit)

- Jose Bautista (S/R) 1988-97 (Bal; ChC; SF; Det; St.L)

- Steve Rosenberg (S/R) 1988-91 (ChW; SDP)

- Scott Radinsky (R) 1990-2001 (ChW; LA; ST.L; Cle)

- Andrew Lorraine (R/S) 1994-2002 (Cal; ChW; Oak; Sea; ChC; Cle; Mil)

- Al Levine (R) 1996-2005 (ChW; Tex; Ana; Tam; KC; Det; SF)

- Scott Schoeneweis (R) 1999-2010 (Ana; ChW; Tor; Cin; NYM; Ari; Bos)

- Jason Marquis: (S) 2000-15 (Atl; StL; ChC; Col; Was; Ari; Min; SD; Cin)

- Justin Wayne (R/S) 2002-04 (Fla)

- John Grabow (R) 2003-11 (Pit; ChC)

- Craig Breslow: (R): 2005-17: (SD; Bos Cle; Min; Oak; Ari; Mia)

- Scott Feldman: (S/R) 2005-17 (Tex; ChC; Bal; Hou; Tor; Cin)

- Dylan Axelrod (R) 2011-15 (ChW; Cin)

- Richard Bleier (R) 2016-Present (NYY; Bal; Mia)

- Max Fried: (S) 2017-Present (Atl)

The pitchers form a less-elite group. Holtzman, Roberts, Stone, Feldman, Marquis, Baumgarten, and Fried spent the majority of their careers as starters; the first five occupy half the spots on the list of top-10 winningest Jewish pitchers. The remainder were spot- and middle-relievers who started the occasional game, some enjoying lengthy careers in this role for multiple teams.24

Holtzman pitched two no-hitters, made two All-Star teams, and won 174 games (nine more than Koufax) in fifteen seasons; he was the third starter on the three-time World Series champion A’s of the mid-’70s. (He also hit the lone World Series home run by a Jewish player in the long gap between Greenberg in 1945 and Bregman and Pederson in 2017). Stone won the AL Cy Young Award in 1980 (the only Jewish Cy Young winner other than Koufax), going 25-7. Holtzman (1970) and Roberts (1971) had better seasons measured by WAR and other metrics. In addition to a decade-plus career as a middle-reliever (including pitching 61 games for the 2013 World Series champion Red Sox), Breslow attended Yale and considered becoming a doctor before pursuing a life in baseball.25

Two pitchers remain active through the shortened 2020 season. Fried won 17 games with a 4.02 ERA and 173 strikeouts in his first season as a full-time starter in 2019, then went 7–0 with a 2.25 ERA in the COVID-19-shortened 2020. Bleier has been an effective reliever since 2017, sporting a 9-2 lifetime record with four saves.

B. The Jewish Narrative

Many of these players were known among teammates, fans, and media for their Judaism during their careers. Epstein carried the nickname “Super Jew;” one writer described him as “Mickey Mantle bred on blintzes and gefilte fish.” Epstein’s A’s teammate Holtzman became known as “Jew” or “Regular Jew.” Following the murder of 11 Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics in 1972, both sported black fabric strips on their uniforms.26 As mentioned, Green received invitations to Bar Mitzvahs in the Toronto area.27 Other players describe invitations to people’s homes for Shabbat and High Holy Days.28 Bregman’s Judaism is a flashpoint for a segment vested in his continuing development into greatness.29

Using 1966 as the starting point, the story opens with an adjacent game. Yom Kippur fell on Saturday in late September. Koufax pushed his start against the Cubs to Sunday afternoon. His opponent was Holtzman, a rookie left-hander who had pushed his own start back after telling his manager that he observed the holy days. The rookie Jewish pitcher outdueled the greatest Jewish pitcher, pitching a two-hit complete game with eight strikeouts in a 2–1 victory; Koufax gave up four hits and struck out five in his last regular-season loss before retiring following the season.30 Holtzman’s mother had hoped both would earn no-decisions so neither Jewish pitcher would lose.31

There is a generational divide among the players. Holtzman never pitched on Yom Kippur. Blomberg sat out Kol Nidre games in 1971 and 1974 and made clear early in his career that he could not and would not play on the holy day.32 Epstein played following the end of Yom Kippur as a late-season call-up in 1966, and sat out a late-season afternoon game in 1971 as the starting first baseman for a division champion after it had clinched the title.

Green’s emergence in the mid-90s as the first Jewish star in a quarter century reignited the Yom Kippur debate. The play-or-not question gained strength because it focused on a high-profile star, someone central to his team’s success and expected to play every day. Green endured greater scrutiny and criticism on the subject than did his contemporaries; greater pressure to follow earlier stars such as Greenberg, Al Rosen, and Koufax in not playing; and more explicit suggestions that by playing he had failed as a Jew.33 Green picked his spots. He did not play on Kol Nidre 5762 (in 2001), the holy day falling several weeks after 9/11. He split the difference in 2004, playing on Kol Nidre and sitting the following afternoon, while doing the converse in 2007.

Youkilis is most consistent among recent players, sitting multiple Kol Nidre games, as well as a two-game evening/day combination in 2007. Bautista started a game on Kol Nidre during his rookie year but would not attend Yom Kippur games the remainder of his career.34 Lorraine and Breslow attended games, were in uniform, and were available to pitch. Lorraine attended services in the morning before going to the park.35 Breslow fasted.36 Breslow said that appearing at the park “weighed heavily” on him, but he could not shake the belief that as a non-star player he lacked leverage to demand the day off.37

But no current player — in particular no current star player — talks about sitting on the holy day. Kinsler played every Yom Kippur on which his team had a game. No news stories raised the prospect of Bregman, Pederson, or Fried not playing or not being available in those 2019 Division Series games and none made an issue of their playing.38

This narrative must account for the fact that most of these players — current and past — are not religiously observant, especially the several from mixed marriages. Epstein was unique in this respect, announcing “I put on tefillin at different shuls in different cities. I was Bar Mitzvahed. I can read Hebrew. I’m a Jew.”39 Game One of the 1973 ALCS between the A’s and Orioles fell on Yom Kippur 5734; Holtzman, not scheduled to pitch for the A’s, attended synagogue in Baltimore with the Orioles owner.40 Greenberg attended synagogue in 1934 and received a standing ovation; he described it as one of the times in his life he felt like a hero.41 Bautista and Holtzman were observant and maintained kosher homes.42

Among recent players, many had Bar Mitzvahs (among them Bleier, Bregman, Fried, Lorraine, and Youkilis) and most express deep pride in their Jewish heritage. Green’s father said that baseball placed his son in touch with his Judaism.43 Many have played for Israel in the World Baseball Classic or the Olympics, including Kinsler, who relocated to Israel upon his 2020 retirement.44

But not playing on the holy day lacks force for these players, even those raised in the shadow of Koufax and for whom High Holy Day attendance was part of their Jewish upbringing.45 Kinsler described celebrating Passover and Chanukah with his Jewish father’s side of the family and embraced that part of his identity, but did not practice Jewish rituals, including observing the holy days.46 Explaining his decision to play on Kol Nidre in 2004 (a game for which his rookie teammate Youkilis dressed but did not play), Gabe Kapler said it made no sense for him to miss one important game on one day when he was not religiously observant 364 days of the year. While expressing pride in his Jewishness and welcoming the chance to serve as a role model as a Jewish athlete, sitting out the game was not part of that identity.

David Leonard argues that the will-he-play question evolves as Jews gain greater acceptance in US society and anti-Semitism decreases.47 This works in conflicting directions. On one hand, by not playing, Greenberg and Koufax — operating in eras of greater and more explicit anti-Semitism in which Jews occupied a more tenuous space in American society48 — made it safe to express Jewish identity.49 On the other, Greenberg and Koufax rendered it unnecessary for current players to demonstrate that identity by not playing; Judaism is part of them and they can move through baseball and American society without calling attention to it. Even recent upticks in anti-Semitism seem unlikely to manifest in widespread criticism of a Jewish player who chooses not to play on Yom Kippur.50

2. The Koufax Curse by the Numbers

This part turns to the numbers, for teams and players. The sample of players in the study is naturally limited. The number of Jewish major leaguers is small, which is why it is the subject of many books.51 Howard Megdal wrote that, as of 2008, fewer than 160 Jews, broadly defined, have played in the majors, representing less than one percent of players in MLB history. Focusing on a subset of 18 nonpitchers and 18 pitchers — rather than looking at every Jewish-identifying player — further shrinks the sample, while centering it on players more likely to play in a typical game.

The sample of games also is naturally limited. Jewish holy days run from sundown to sundown, so the study focuses on two days and, at most, two games each season. Teams may have no games scheduled on Yom Kippur.

Following the Hebrew calendar, I treat three categories of games as “on” Yom Kippur: 1) evening, when Kol Nidre and the fast have begun; 2) during daylight the following day, which I define as beginning before 6:00 p.m.; and 3) first pitch between 6:00 p.m. and 8:00 p.m. the following evening, beginning as the holy day is ending for some number of Jews but finishing after its conclusion.

A. Team Records

The first consideration is team success when Jewish players play. The events of 2019 were striking less because of the performance of three Jewish players than for the fact that all teams lost, two of them series-deciding games.52

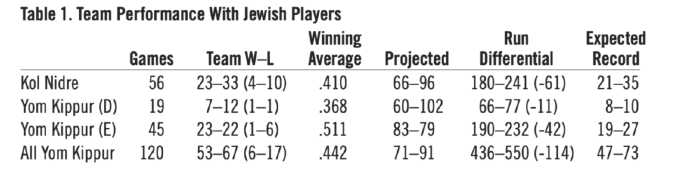

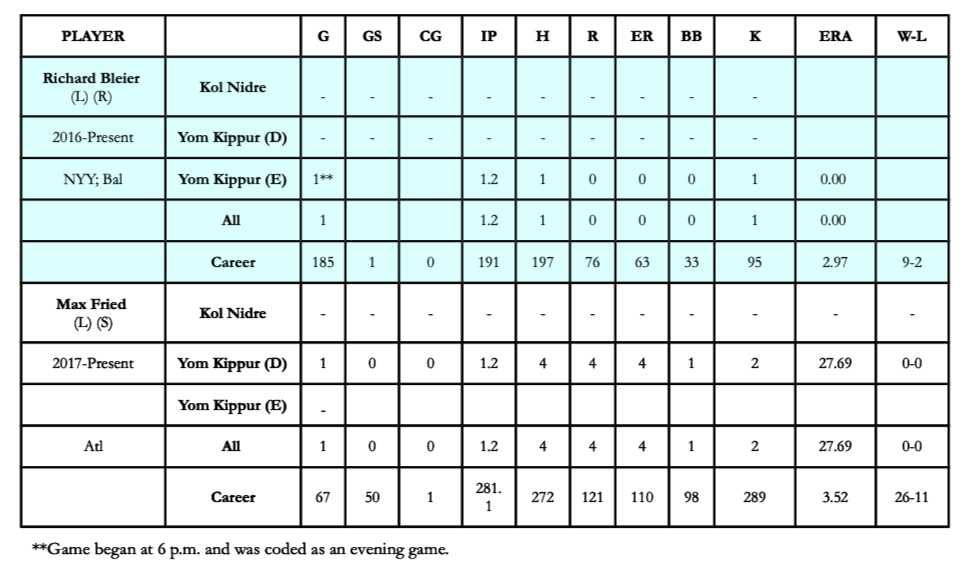

Table 1 shows team performance when Jewish players play, broken by three classes of Yom Kippur games and all holy-day games. In the “Team W-L” column, the larger record is for all players, while parentheses show records when the Jewish player is a pitcher.

Table 1. Team Performance With Jewish Players

In 120 games, teams are 53–67 when a Jewish player plays at any point on Yom Kippur, 14 games below .500 — ten games under on Kol Nidre, five games under before sundown the following day, and one game over in games played as or after the holy day is ending. This is a .442 winning average, projecting to a 71-91 record in a 162-game season. Teams won six of 23 games in which the Jewish player is a pitcher, a .261 winning average.

Teams had a –114 run differential when Jewish players played, including a –61 differential on Kol Nidre and a –40 differential at the end of the holy day. Interestingly, teams outperformed that run differential. A team with those numbers of runs scored and allowed expects to win 47 of 120 games (.392 winning average), six fewer than teams won.

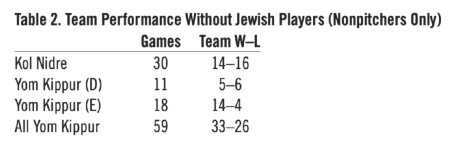

Table 2 shows team records when Jewish nonpitchers (excluding pitchers) do not play on Yom Kippur, whether for religious or other reasons.

Table 2. Team Performance Without Jewish Players (Nonpitchers Only)

Teams remain two games below .500 on Kol Nidre and one game below during Yom Kippur day. But the record jumps to ten games above .500 in after-holy-day evening games. This produces a total of seven games over .500 in about half the number of games.

B. Nonpitchers

1. Total Statistics

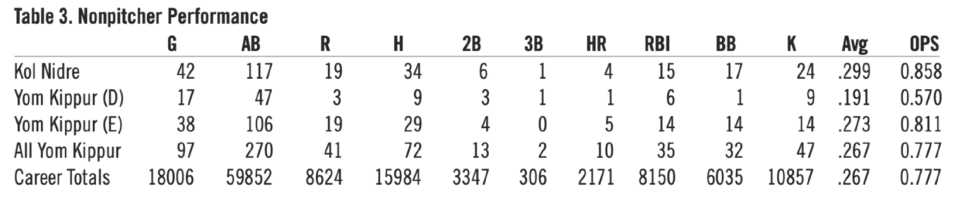

Table 3 shows combined performance for the 18 nonpitchers in the study, again broken by three categories of games, all holy-day games, and careers.

Table 3. Nonpitcher Performance

As a group, nonpitchers match combined career batting average and OPS for all holy-day games. They significantly out-perform on Kol Nidre — surprising, given team records in those games. Only in Yom Kippur day games, the smallest of the three categories, do they under-perform career numbers to a significant degree. Power and run-production numbers are not great, but the sample size is small.

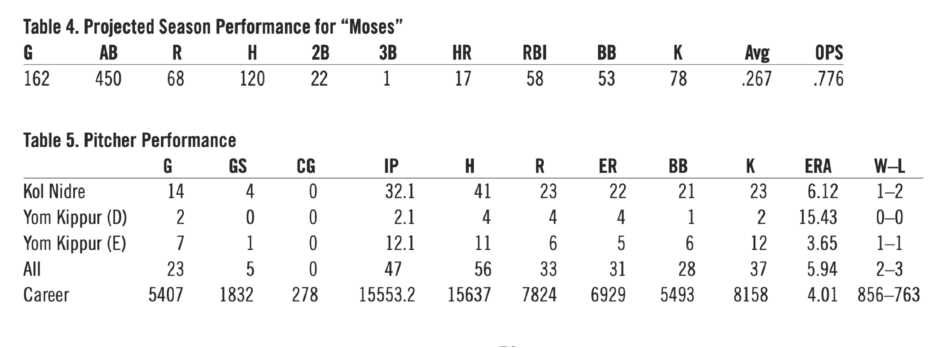

Ninety-seven games represent 59.9 % of one season. Imagining these as the statistics for one Jewish nonpitcher (call him “Moses”), Table 4 projects Yom Kippur performance for a 162-game season.

Table 4. Projected Season Performance for “Moses”

Table 5. Pitcher Performance

Moses finishes a full season with a .267 average, .776 OPS, with 120 hits, a modest 17 home runs, 58 RBI, a slash line of .267/.343/.433, and more strikeouts than walks.

2. Individual Statistics

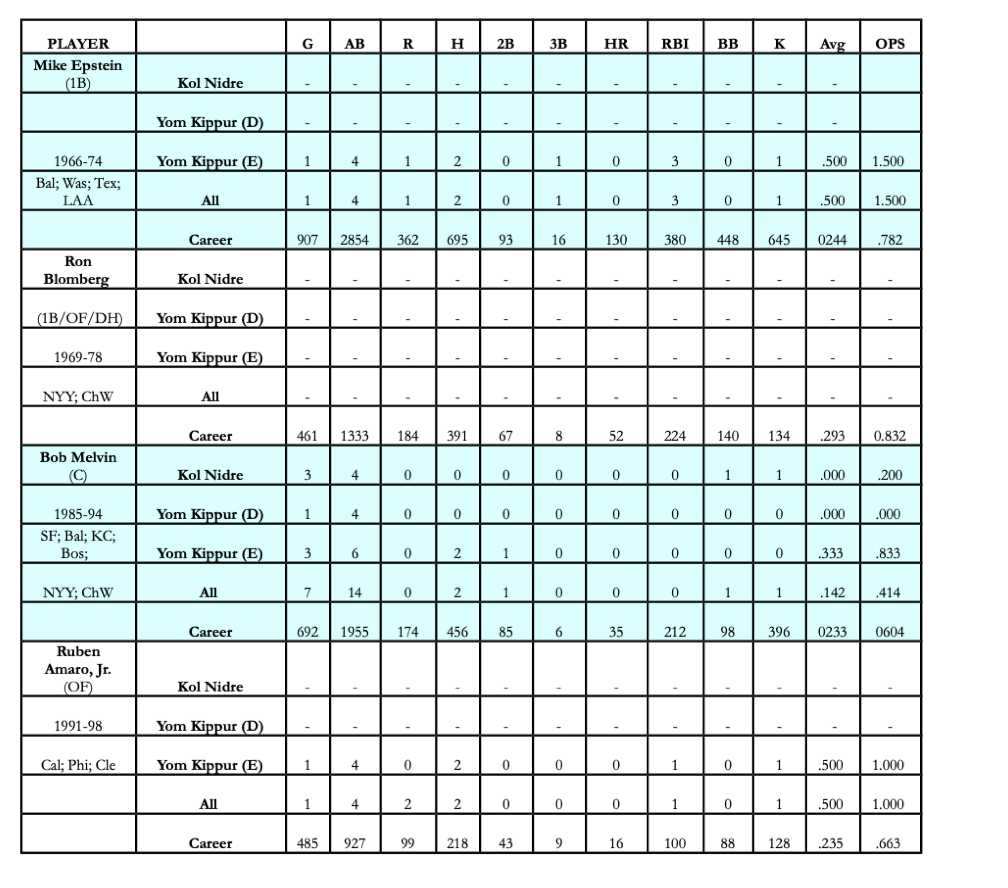

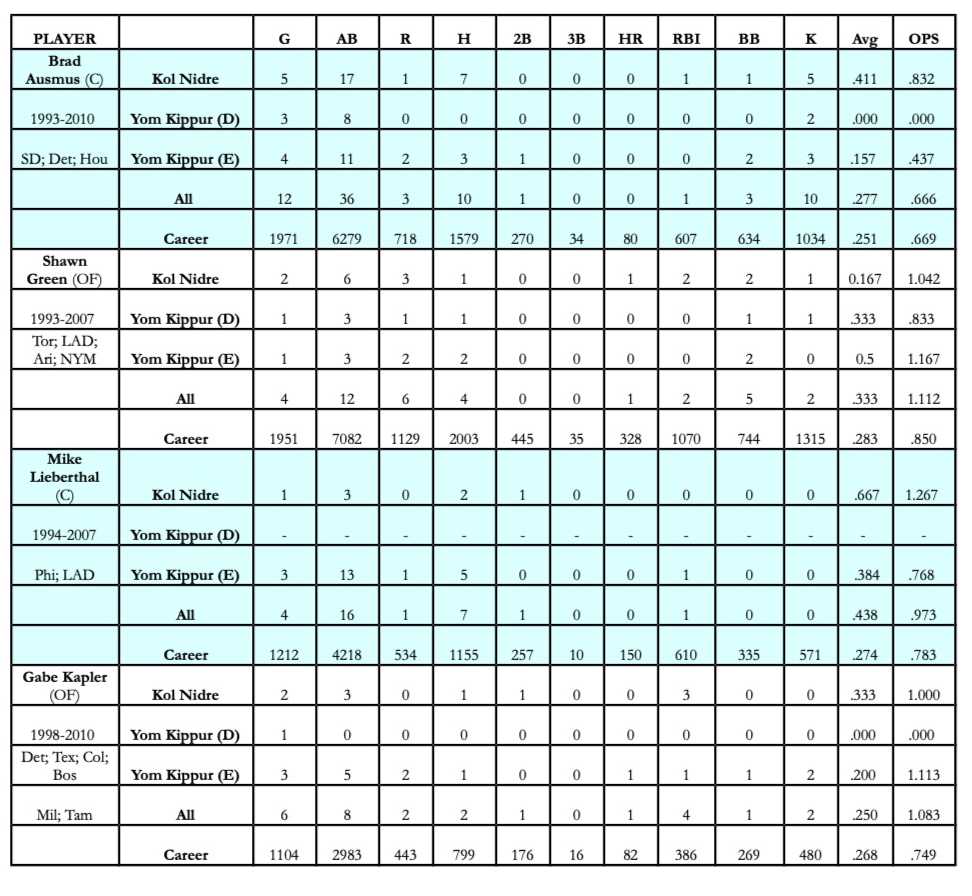

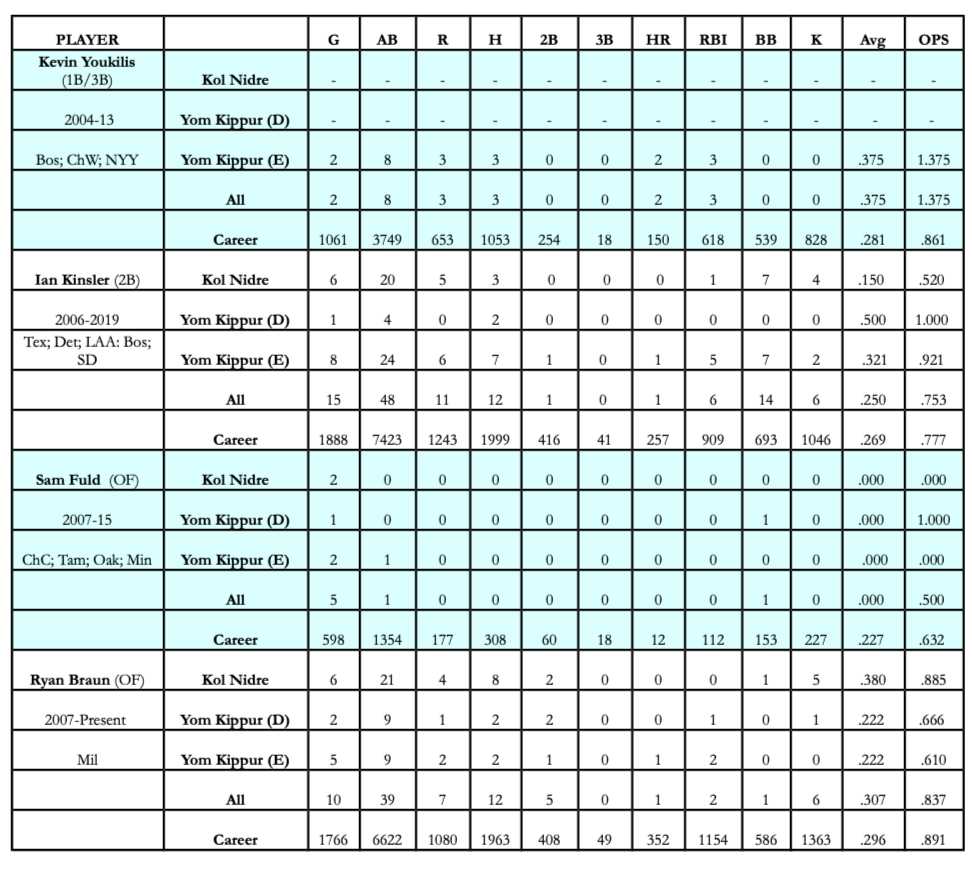

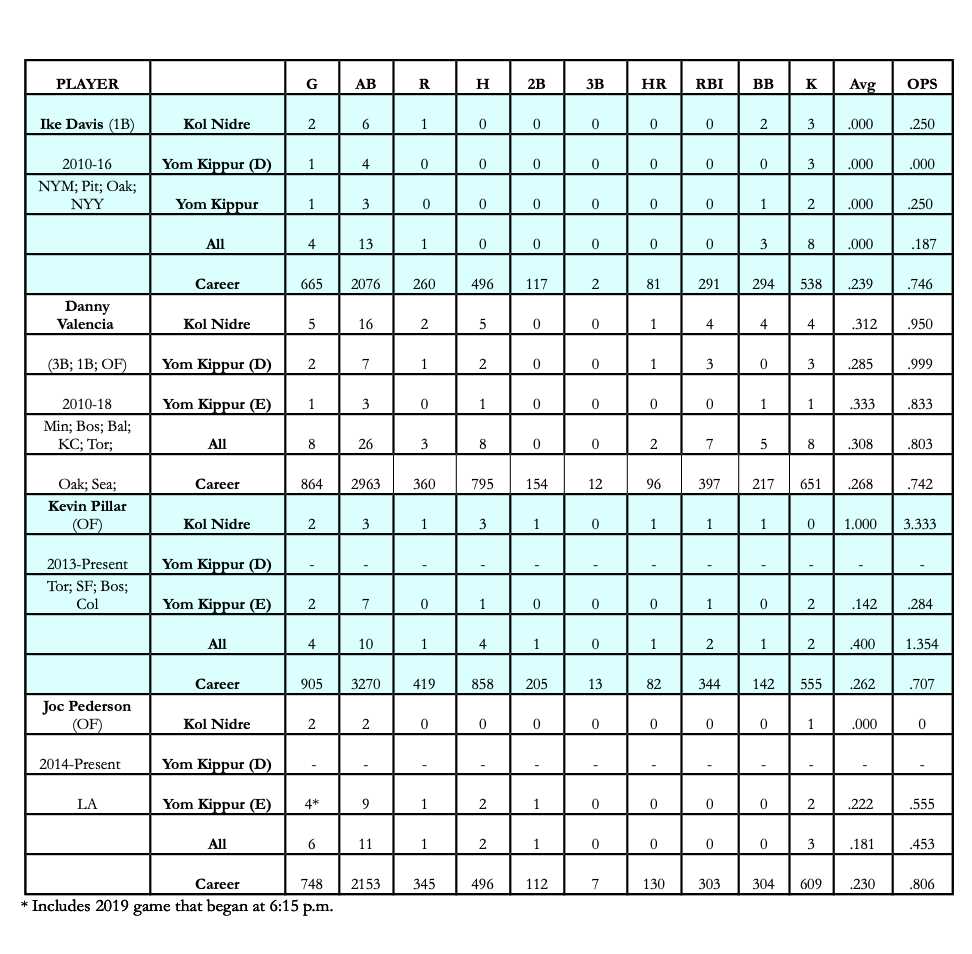

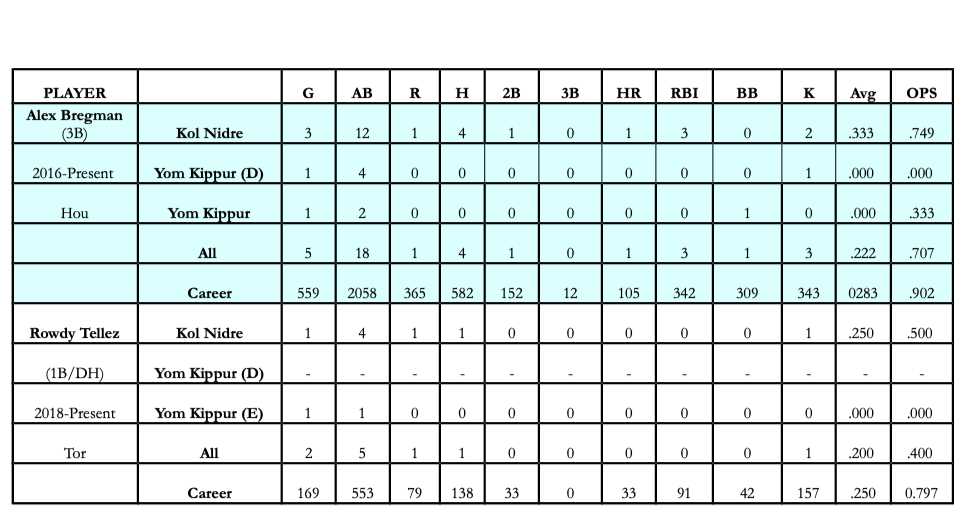

Appendix A shows career performance for the 18 nonpitchers, listed in chronological order of MLB debut.54 For each player, it lists performance in the three categories of games, all holy-day games, and career.

Kinsler (15), Ausmus (12), and Braun (10) have played the most games, a reminder of the small sample size. Ausmus significantly outperformed his career stats on Kol Nidre. Kinsler hit well in eight end-of-holy-day games, but otherwise under-performed his career numbers for the full holy day.

Youkilis never played on Kol Nidre or during the day, but went 2-for-3 with two home runs and 3 RBIs in a 2009 post-fast loss. Pillar provides the standout game, going 3-for-3 with a solo home run in 2015 (Kol Nidre 5776) in a loss. Epstein played at the end of the holy day as a late-season call-up in 1966, going 2-for-4 with a triple and 3 RBIs.

In 2004, Green played on Kol Nidre 5765 so he could sit the following afternoon; he went 1-for-3 with a two-run home run in an important late-season victory. Bregman played two Yom Kippur games in 2017. On Kol Nidre, he went 3-for-4 with a home run and 3 RBIs in a late-season 3-2 win; the following afternoon he went 0-for-4 in a loss.

As a rookie in 2010 (5771), Valencia enjoyed the best overall Yom Kippur. On Kol Nidre, he went 2-for-3 with a solo home run, the lone run for his Twins in a loss. The following afternoon, he went 2-for-4 with a home run, driving in three of the team’s four runs in a victory. Valencia arguably enjoyed the best Yom Kippur career, with eight hits, including two home runs, five walks, and seven runs batted in in eight games.

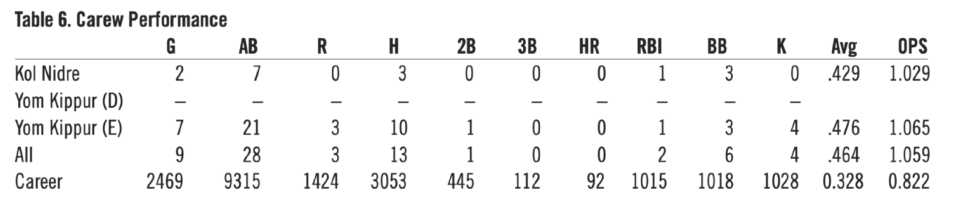

C. Pitchers

1. Total Statistics

Table 5 shows combined performance for the eighteen pitchers in the study.

Pitchers provide a smaller sample than nonpitchers, with fewer games and fewer innings pitched. Eighteen of 23 Yom Kippur appearances were in relief, the average appearance lasting two innings. A Jewish pitcher earned a decision in five games in which any Jewish pitcher appeared, going 2-3; the win or loss was charged to a different, non-Jewish pitcher in 18 games. There was one save earned.

The sample size for pitchers is too small to extrapolate over a full season.

2. Individual Statistics

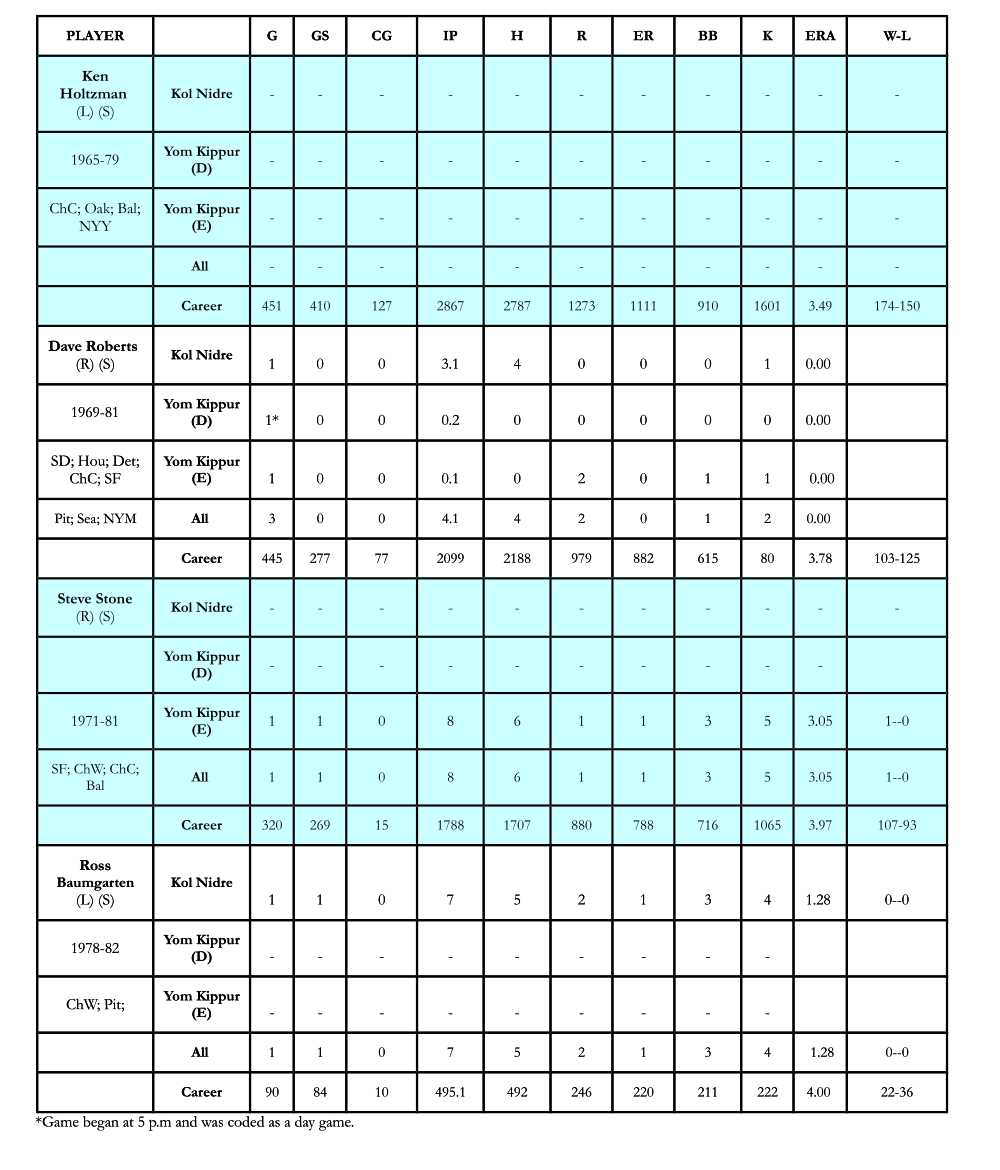

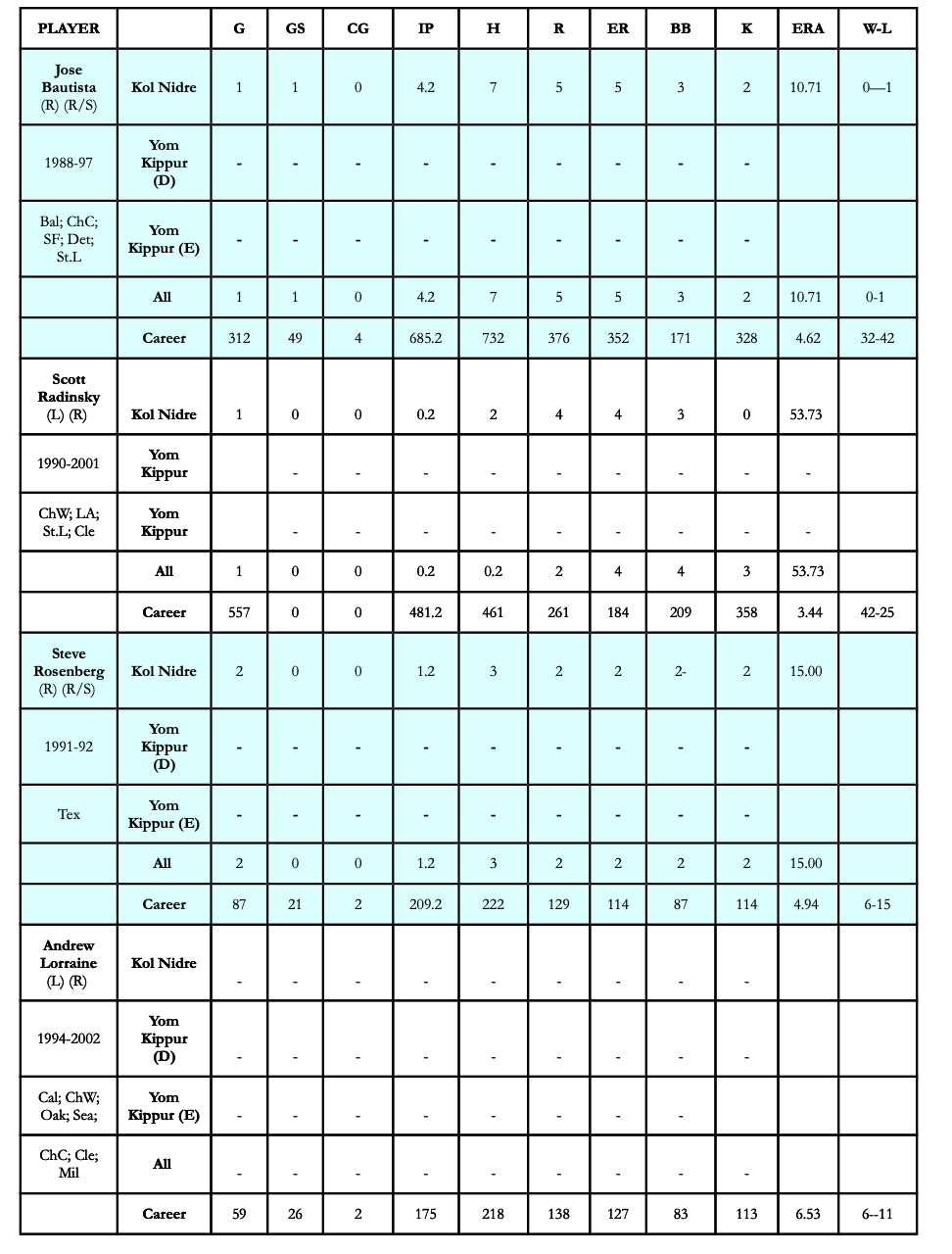

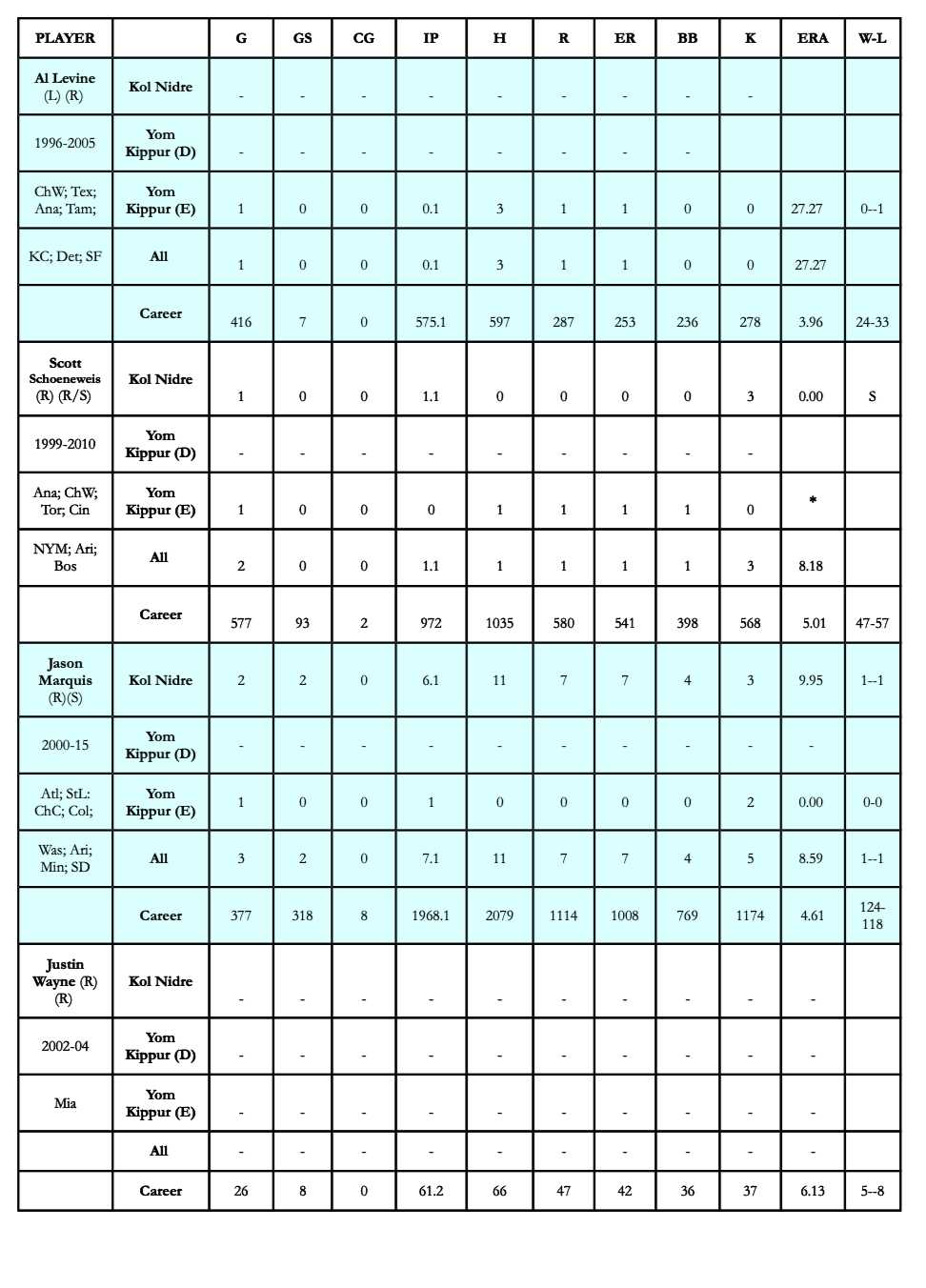

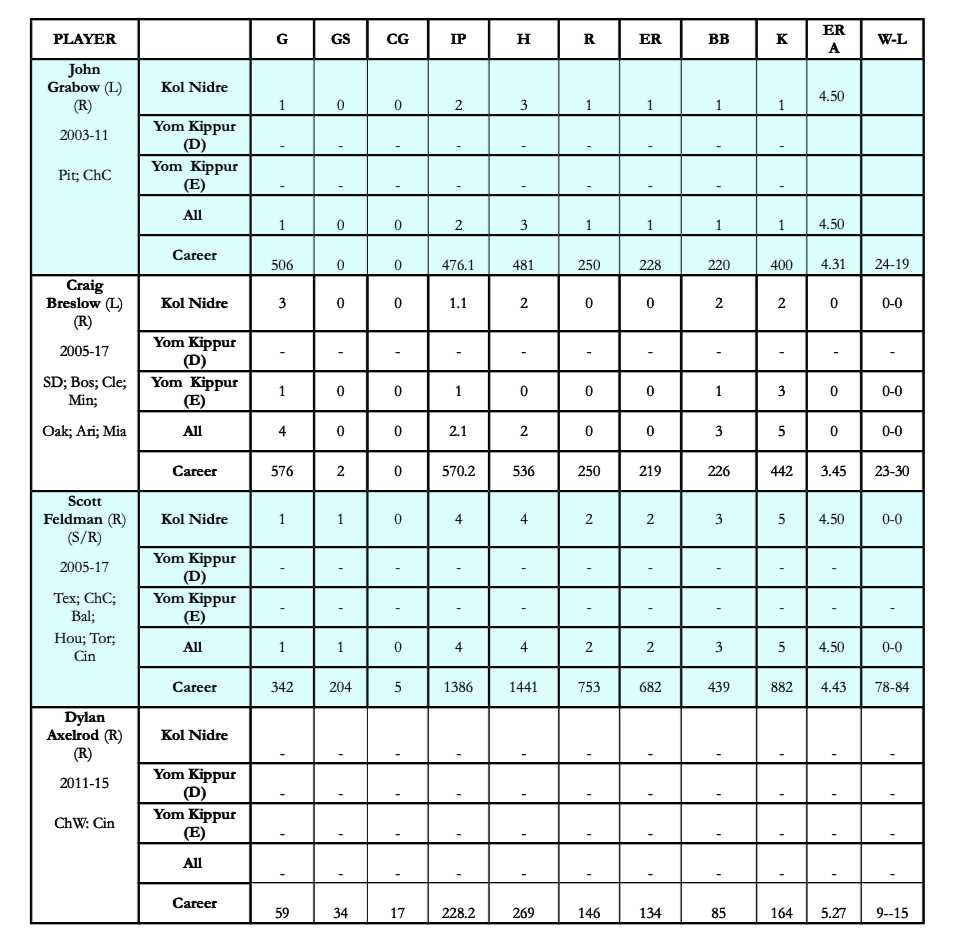

Appendix B (below) shows career performance for the 18 pitchers, listed in chronological order of MLB debut.56 The first parenthetical indicates whether he threw lefty or righty; the second indicates starter, reliever, or both.

Breslow made the most appearances with four, all in relief, followed by three for Marquis (two starts) and for Roberts (all in relief). Four pitchers on the list never appeared on the holy day, although only Holtzman appears to have done so as a religious decision, as opposed to not being needed.

The best combined pitching performance occurred in 1980 (Yom Kippur 5741). On Kol Nidre, Baumgarten surrendered one earned run on five hits with four strikeouts in seven innings and left with a 3-2 lead; he earned no decision when the bullpen surrendered the lead. As the holy day ended 24 hours later, Stone surrendered one run on six hits in eight innings, striking out five in a win, continuing his dream season.

Marquis earned the other win in 2001 (Kol Nidre 5762), allowing one run on five hits in six innings. Schoeneweis earned the lone save in the study, striking out three of the four batters he faced to preserve a 2007 (Kol Nidre 5768) win. Breslow never allowed a run and struck out five of his seven outs — an impressive performance considering he fasted.

The three losses reflect poor outings. Marquis surrendered six runs on six hits in 1/3 of an inning in a 2010 (Kol Nidre 5771) loss. Levine surrendered the winning run on three hits in the bottom of the ninth in relief in a 2002 end-of-holy-day game (Yom Kippur 5763). Bautista lost the only Yom Kippur game he pitched in 1988 (Kol Nidre 5749) — five runs on seven hits in 4 2/3 innings.

Several poor relief performances have come in games that the team trailed, resulting in a team loss but no decision. Fried surrendered four runs on four hits in 1 2/3 innings in his 2019 playoff game, but the Braves trailed 4–0 before Fried entered in the first inning of an eventual 13-1 loss. Radinsky surrendered two hits, three walks, and four earned runs in less than one inning in 1990, but his White Sox trailed 7-4 on the way to a 13-4 loss.

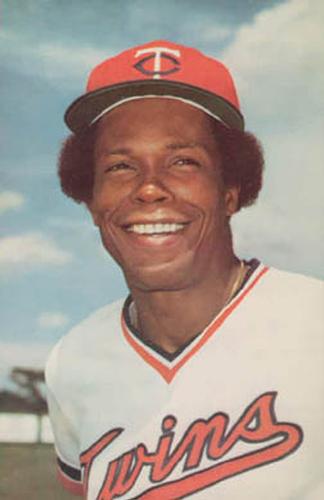

D. The Special Case of Rod Carew

Preliminary discussions with colleagues about this article and the players to include in the study precipitated a miniature debate: What of Rod Carew, the Hall of Fame infielder for the Minnesota Twins and California Angels from 1967–85? Carew occupies a unique space in the conversation about Jews and baseball, earning him a unique space in this study.

Preliminary discussions with colleagues about this article and the players to include in the study precipitated a miniature debate: What of Rod Carew, the Hall of Fame infielder for the Minnesota Twins and California Angels from 1967–85? Carew occupies a unique space in the conversation about Jews and baseball, earning him a unique space in this study.

Were Carew Jewish, he would be on the Mount Rushmore of Jewish players (Mount Sinai?) with Koufax and Greenberg, while perhaps waiting for Bregman to fulfill his potential and form a quartet. Although he lacked power, Carew was among the best hitters of his generation. He had more than 3,000 career hits, ranking ninth all-time in singles; a career batting average of .328; and a career OPS of .822. He was an 18-time All Star; won 1967 American League Rookie of the Year; and won 1977 American League Most Valuable Player, when he batted .388 (second-highest batting average since 1931 by a player not named Ted Williams) with an OPS of 1.019. He was elected to the Hall of Fame on the first ballot in 1991. And MLB placed his name on the AL batting champion award in 2016.57

Carew was born to an African American father and Panamanian mother with West Indian roots. He was married to a Jewish woman during his playing career and raised three Jewish daughters.58 Carew appeared on the covers of Time and Sports Illustrated in 1977 wearing his Twins uniform and a chai (a pendant spelling the Hebrew word “life”) that he wore on the field. He spoke during his playing career about converting to Judaism.59 Baseball writer Thomas Boswell described him in an essay titled The Zen of Rod Carew as a “Jewish convert.”60 Most famously, comedian Adam Sandler included Carew in his first Chanukah Song, including Sandler’s vocal aside: “He converted.”

But Carew never converted, which he explained in a phone call to Sandler.61 Although he took preliminary steps, he never completed the process. Carew’s connection to Judaism made news when his youngest daughter died of a rare form of leukemia in 1996; her mix of African, West Indian, and Panamanian ancestry on her father’s side and Eastern-European Jewish ancestry on her mother’s made finding a bone marrow donor difficult.62 Stories did not mention Carew having converted.

Nevertheless, Carew skipped Yom Kippur games five times.63 In 1980, after missing a Kol Nidre evening game, he did not enter the following evening game until the ninth inning, well after the shofar had sounded and the fast had ended. In 1982, he played in a late-afternoon game prior to Kol Nidre, intending to leave had the game run past eight o’clock.64 In 1977, while Carew’s Twins played in Kansas City on Kol Nidre, Carew was home in Minneapolis; news reports conflicted about whether he went to seek medical attention for an ailing arm or whether he had planned to be home to observe the holy day with his family.65

Non-conversion makes Carew not Jewish for inclusion with the 18 Jewish nonpitchers. But his connection to Judaism and his intentional avoidance of playing on Yom Kippur compel his consideration in the study.

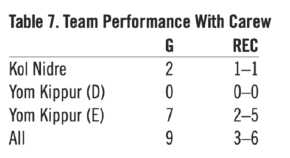

Table 6 shows Carew’s individual performance in nine games — two on Kol Nidre, none during Yom Kippur day, and seven in the late-afternoon or evening following the end of the holy day — while Table 7 shows team records in those ten games.

Carew’s Yom Kippur experience mirrors that of the Jewish players in the study. He performed well, with numbers (in a small sample size of nine games and 34 plate appearances) outstripping even his Hall of Fame career numbers. And his team lost more than it won, although they at least broke even when he played on Kol Nidre.

III. A Koufax Curse?

We conclude with the question that begat this paper: does the Koufax Curse exist, even as a correlative matter?

At the individual level, the answer appears to be no. As a group, Yom Kippur hitting numbers for nonpitchers match their career batting average and OPS, if limited power and run production, with higher numbers on Kol Nidre than in games during the following afternoon or evening. Pitcher performances have been mixed, with several good starts and relief appearances balanced against some poor games.

At the team level, however, something strange happens. Teams are 14 games under .500 in all Yom Kippur games, including ten games under on Kol Nidre. When a Jewish player plays on Yom Kippur, their teams are the equivalent of a 71-91 team. And they project to a worse record.

The events of October 2019 (Yom Kippur 5780), with which the article began, reflect this trend. Neither Bregman nor Pederson played poorly. Bregman had one hit in four at-bats and made some plays in the field, but the Astros surrendered three runs in the first inning. Pederson had two hits, including a double that was initially ruled a home run, scored one run, and made two plays in the outfield, but the bullpen blew a late lead. Fried pitched poorly in surrendering four runs in an inning-plus of work, but the game was lost before he entered.

In other words, any curse appears to target not Jewish players, but their non-Jewish teammates, with consequences befalling the whole team. Perhaps this warrants a new approach to Yom Kippur — teams should welcome and encourage Jewish players to sit these games. The media can retire the historic narrative of a dilemma between team and faith or of a player letting his teammates down by missing one game that could decide the season.66 The story becomes that the Jewish player helps his team and supports his teammates by not playing, at least for one or two games. The player becomes a hero to Jewish fans, offers the team an ironically better chance at victory, and perhaps appeases Hashem.

This revised narrative recalls the biblical story of Jonah, fittingly read and studied on Yom Kippur.67 God’s anger at Jonah causes a storm certain to wreck the boat and kill everyone on board, so Jonah urges his shipmates to throw him overboard. The crew reluctantly does so, after which the “sea ceased from its raging.” Perhaps by casting their Jewish teammates into the sea of a day off, the storm of defeat will cease from raging that day.

On the other hand, overall team record is better than it should be, given performance. While teams won 53 games with a Jewish player, their run differential reflects a team that should have won 47 games. Perhaps winning six more games than expected reflects Hashem smiling upon these teams and their Jewish players.

On a third hand (invoking the oft-repeated phrase “two Jews, three opinions”68), teams do not win when their Jewish players rest on Kol Nidre or during the following day, finishing a combined three games below .500. The foundational events that beget any curse reflect this. With Greenberg sitting during Yom Kippur day in 1934, the Tigers lost — although they had built a lead in the pennant race thanks in part to Greenberg hitting two home runs in a Rosh Hashanah win nine days earlier.69 With Koufax sitting in a Minneapolis hotel room, the Dodgers lost Game One of the 1965 World Series, with future Hall of Famer Don Drysdale surrendering seven hits (two home runs) and seven runs (three earned) in 2 2/3 innings. The story is that when Dodger manager Walter Alston pulled him from the game, Drysdale said, “I bet you wish I was Jewish today, too.”70 Team records without Jewish players improve in evening games, or after the sounding of the shofar and breaking of the fast.

Perhaps the solution is that no one should play on Yom Kippur, at least not teams with Jewish players. Like public schools or the Supreme Court, everyone should benefit from the off day that the Hebrew calendar and a Jewish population provides.71 Jews can recommit to their faith. And everyone can be ready to play the following day.

I make both suggestions with tongue in cheek, of course. MLB should not stop playing on Yom Kippur, nor should it urge Jewish players not to play. But these numbers might relieve Jewish players of the belief, expressed by Breslow, that they lack the leverage to request the day off.

HOWARD M. WASSERMAN is Professor of Law and Associate Dean for Research and Faculty Development at FIU College of Law, where he has taught since 2003. His research focuses on civil rights litigation, freedom of speech, and baseball rules. His baseball writing includes Infield Fly Rule Is in Effect: The History and Strategy of Baseball’s Most (In)Famous Rule (Durham: McFarland Press 2019); “Against Stealing First Base,” NINE: Journal of Baseball History and Culture (forthcoming 2020); “Sport and Expression, Sport as Expression,” FIU Law Review (forthcoming 2020); “When They Were Kings: Greenberg and Koufax Sit on Yom Kippur,” Tablet Magazine (2016); and “If You Build it, They Will Speak: Public Stadiums, Public Forums, and Free Speech,” 14 NINE: Journal of Baseball History and Culture 15 (2006).

Acknowledgments

Thanks to David Fontana, Michael Helfand, Roberta Kwall, David Leonard, Peter Oh, Howard Simon, and Spencer Weber Waller for help and comments. Thanks to Alexis de la Rosa, Jesse Goldblum, Jordan Roth, Carlos San Jose, and Jesse Stolow for research assistance.

Sources

Unless otherwise stated, all game, season, and career statistics were found on player biography pages on Baseball-Reference.com. All scores and details were found on box scores for the relevant games on Baseball-Reference.com.

Appendix A: Nonpitchers

(Click images to enlarge)

Appendix B: Pitchers

(Click images to enlarge)

Notes

1 16 Leviticus 1-34; 58 Isaiah 3-6; Irving Greenberg, The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays (New York: Touchstone, 1993 184-85.

2 Edward Sherman, “L’dor v’dor: The annual re-telling of the Sandy Koufax Yom Kippur story,” Jewish Baseball Museum. Oct. 10, 2016, http://jewishbaseballmuseum.com/spotlight-story/tradition-annual-re-telling-sandy-koufax-yom-kippur-story/.

3 Armin Rosen, “The Koufax Curse,” Tablet, Oct. 10, 2019, https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/sports/articles/the-koufax-curse.

4 Jane Leavy, Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy. (New York: HarperCollins, 2002), 170-71, 183-84; Larry Ruttman, American Jews & America’s Game: Voices of a Growing Legacy in Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2013), 129; David J. Leonard. “To Play or Pray? Shawn Green and His Choice Over Atonement,” Shofar 25, no.4 (2007): 159 & n.25; Matt Rothenberg, “Sandy Koufax Responded to a Higher Calling on Yom Kippur in 1965,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, https://baseballhall.org/discover/sandy-koufax-sits-out-game-one.

5 Mark Kurlansky, Hank Greenberg: The Hero Who Didn’t Want to Be One (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011); Leonard, “To Play or Pray?,” 157-58; Howard M. Wasserman, “When They Were Kings: Greenberg and Koufax Sit on Yom Kippur.” Tablet Magazine, Oct. 11, 2016, https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/when-they-were-kings-greenberg-and-koufax-sit-on-yom-kippur.

6 Leavy, Sandy Koufax, 171.

7 Rosen, “The Koufax Curse.” Hashem (“the name”) is one of the names Jews use to speak of God.

8 David Fontana, “The Return of the Jewish Athlete.” Huffington Post, Dec. 6, 2017, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/the-return-of-the-jewish-_b_4601775.

9 Jewish Baseball News, http://www.jewishbaseballnews.com/.

10 The Oakland A’s starting lineup for Games One and Four of the 1972 World Series included pitcher Ken Holtzman and first baseman Mike Epstein.

11 In Howard Megdal’s ranking of the top Jewish players by position, no top-five player at any starting position played the bulk of his career during the 1980s and the only player on his All-Time Jewish team who played the bulk of his career in the ‘80s is a relief pitcher. Howard Megdal, The Baseball Talmud: The Definitive Position-by-Position Ranking of Baseball’s Chosen Players (New York: HarperCollins, 2009), 287-888.

12 Steve Wulf, “The bat belongs to Shawn Green, the Mitzvah is his breakout for the Blue Jays.” ESPN.com, July 10, 2012, https://www.espn.com/espn/magazine/archives/news/story?page=magazine-19990614-article43.

13 Robert L. Cohen, “How the Jewish Baseball Superstars Have Handled the High Holiday Conflict,” St. Louis Jewish Light, Sept. 26, 1984, 3.

14 Jesse Bernstein, “The Greatest Jewish Baseball Players of All Time, By Position,” Tablet Magazine, July 29, 2016, https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/the-greatest-jewish-baseball-players-of-all-time-by-position; David Hazony, “Why Israel’s Sudden Baseball Prowess Actually Means Something.” The Forward, Mar. 10, 2017, https://forward.com/opinion/365646/why-israels-sudden-baseball-prowess-actually-means-something/.

15 Leonard, “To Play or Pray?”, 151, 160-61; http://www.jewishbaseballnews.com/; http://jewishbaseballmuseum.com/; http://www.jewornotjew.com/category.jsp?CAT=Athletes%20and%20Coaches.

16 Leonard, “To Play or Pray?”, 151; Sherman, “L’dor v’dor.”

17 Rosen, “The Koufax Curse.”

18 No World Series game has been played on Yom Kippur since Game One in 1978 fell on Kol Nidre. No Jewish player has missed a World Series game since Koufax. And none will repeat that feat, as Yom Kippur and the World Series no longer overlap. Under the current (and expanding) post-season format, the World Series never will begin earlier than October 20, while Yom Kippur cannot fall later than October 14. This adds to Koufax’s legend.

19 The Hebrew word for life is chai. It is spelled in Hebrew with two letters, the 8th and 10th in the alphabet. This gives the word a numerical value of 18.

20 Traditional Judaism is matrilineal. Observant Jews would not recognize as Jewish a person with a Jewish father and non-Jewish mother, unless the person converted. Reform and more liberal Judaism recognize patrilineal descent.

21 The second iteration of the Washington Senators, that played from 1961-72 before relocating to Dallas-Fort Worth and becoming the Texas Rangers.

22 Jewish Baseball Museum, http://jewishbaseballmuseum.com/stats.

23 Braun’s early-career numbers might have been Hall-worthy, Megdal, The Baseball Talmud, 130, but he has not maintained the pace. His candidacy also may be hurt by his 65-game suspension in 2013 for using performance-enhancing drugs during that MVP season, including defending himself by impugning the integrity of the lab technician who collected his sample. Bernstein, “The Greatest Jewish Baseball Players.” Hall voters have been unforgiving of PED users, and Braun’s response to being caught may not help. David Sheinin, “The key changes that could finally put PED users into the Baseball Hall of Fame,” Washington Post, Jan. 17, 2017.

24 In his position-by-position rankings, Megdal identified 20 Jewish starting pitchers (7 lefty, 13 righty) and 47 Jewish relief pitchers (21 lefty, 26 righty). Megdal, The Baseball Talmud, 181-285.

25 Megdal, The Baseball Talmud, 225; Ruttman, American Jews, 424-25; “Red Sox Reliever Craig Breslow Brings Brains and Jewish Faith to Mound.” Haaretz, Oct. 23, 2014, https://www.haaretz.com/jewish/red-sox-s-breslow-brings-judaism-to-mound-1.5278574

26 Jason Turbow, Dynastic, Bombastic, Fantastic: Reggie, Rollie, Catfish, and Charlie Finley’s Swingin’ A’s (Boston: Mariner Books, 2017), 48-61.

27 Wulf, “The bat belongs to Shawn Green.”

28 Ira Gewanter, “Seven Questions for a Pair of Jewish Birds,” JMore: Jewish Baltimore Living, May 16, 2018, https://www.jmoreliving.com/2018/05/16/seven-questions-for-a-pair-of-jewish-birds/.

29 Armin Rosen, “Is Alex Bregman Having the Best Season Ever By a Jewish Baseball Player?” Tablet Magazine, Sept. 27, 2019, https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/is-alex-bregman-having-the-best-season-ever-by-a-jewish-baseball-player; Dave Sheinin, “Alex Bregman nears MLB greatness set in motion generations ago in D.C. sandlots and boardrooms,” Washington Post, Oct. 4, 2018.

30 Ruttman, American Jews, 214-15.

31 Ruttman, American Jews, 215.

32 “Yankees Edge Bengals.” New York Daily News, Sept. 27, 1971.

33 Leonard, “To Play or Pray?”, 150-51, 160-61.

34 Horvitz & Horvitz, The Big Book of Jewish Baseball, 25-26.

35 George Castle, “A Jewish Lefty: Lefty Lorraine continues tradition.” Jewish World Review, Sept. 22, 1999. http://www.jewishworldreview.com/0999/lorraine.html.

36 “Red Sox Reliever Craig Breslow.”

37 Ruttman, American Jews, 424.

38 Jonathan S. Tobin, “Did we need another Sandy Koufax?” Jewish News Syndicate, October 11, 2019, https://wwwjns.org/opinion/did-we-need-another-sandy-koufax.

39 Turbow, Dynastic, Bombastic, Fantastic, 49.

40 Ruttman, American Jews, 221-22; “A’s, Orioles Call 1st Playoff Game ‘Vital’,” Sacramento Bee, Oct. 6, 1973.

41 Kurlansky, Hank Greenberg, 10.

42 Horvitz & Horvitz, The Big Book of Jewish Baseball, 26; Ruttman, American Jews, 213.

43 Wulf, “The bat belongs to Shawn Green.”

44 Referred to as “Making Aliyah,” or the “act of going up to Jerusalem.”

45 David R. Cohen, “Max Fried’s Birthright from Israel to SunTrust Park,” Atlanta Jewish Times, Aug. 25, 2017, https://atlantajewishtimes.timesofisrael.com/fried-is-working-to-fill-koufaxs-shoes; Gewanter, “Seven Questions.”

46 Ruttman, American Jews, 488-90; Jackie Headopohl, “Kinsler and Ausmus connect with their family roots,” The Jewish News, June 8, 2017, https://thejewishnews.com/2017/06/08/kinsler-ausmus-connect-family-roots/.

47 Leonard, “To Play or Pray?”, 162.

48 Id. at 159-60; Wasserman, “When They Were Kings.”

49 Leonard, “To Play or Pray?”, 162, 165.

50 Jonathan Weisman, (((Semitism))): Being Jewish in America in the Age of Trump (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2018), 11-14, 31.

51 Horvitz & Horvitz, The Big Book of Jewish Baseball; Megdal, The Baseball Talmud; Ruttman, American Jews.

52 Rosen, “The Koufax Curse.”

53 Snyder, “MLB All Star Game.”

54 Mike Digiovanna, “A Father’s Prayer: ‘Give Her More Time’: Rod Carew’s Daughter Michelle, in a Battle for Life, Waits for a Bone-Marrow Transplant,” Los Angeles Times, Mar. 3, 1996.

55 Steve Lipman, “Carew Heading Home to Judaism,” The Journal News, Sept. 29, 1977,16B

56 Thomas Boswell, “The Zen of Rod Carew,” in How Life Imitates the World Series (New York: Penguin Sports Library, 1982).

57 Carly Mallenbaum, “Adam Sandler’s ‘Chanukah Song’: Are of those celebs in the song actually Jewish?” USA Today, Dec. 23, 2019, https://www.usatoday.com/story/life/music/2018/11/29/adam-sandler-chanukah-lyrics/2133567002/.

58 “Hall of Famer Rod Carew Ruins Adam Sandler’s Hanukkah Song By Admitting He Isn’t Jewish.” NESN. Last modified Aug. 6, 2012. https://nesn.com/2012/08/hall-of-famer-rod-carew-ruins-adam-sandlers-hanukkah-song-by-admitting-he-isnt-jewish.

59 Ron Lesko. “Michelle Carew: ‘She Was the Light of the World.’” Associated Press. Apr. 21, 1996.

60 R. Cohen, “How the Jewish Baseball Superstars,” 3.

61 “Angels,” 13.

62 Lipman, “Carew Heading Home to Judaism,” 16B; “Arm Injury.”

63 Megdal, The Baseball Talmud, 67.

64 Leonard, “To Play or Pray?”, 153-54; R. Cohen, “How the Jewish Baseball Superstars,” 3; Sherman, “L’dor v’dor.”

65 Leonard, “To Play or Pray?,” 158, 163; Tobin, “Did we need another Sandy Koufax?”; Wolpe, “A Rabbi’s Advice for Shawn Green,” BeliefNet, Sept. 24, 2004, https://wwwquestia.com/library/journal/1Ps-1318031171/to-play-or-pray-shawn-green-and-his-choice-over-atonement; Marc Tracy, “Marquis to Pitch on Kol Nidre,” Tablet Magazine, Sept 14, 2010, https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/marquis-to-pitch-on-kol-nidre.

66 Greenberg, The Jewish Way, 213.

67 1 Jonah 12-16.

68 Sandee Brawarsky & Deborah Mark, Two Jews, Three Opinions: A Collection of Twentieth-century Jewish Quotations (New York: Pedigree Books, 1998).

69 Kurlansky, Hank Greenberg; Leonard, “To Play or Pray?,” 157-58; Wasserman, “When They Were Kings.”

70 Leavy, Sandy Koufax, 184-85.

71 Nathaniel Lewin, “When Jewish justices got the Supreme Court to shut down on Yom Kippur,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Sept. 29, 2017, https://www.jta.org/2017/09/29/opinion/when-jewish-justices-got-the-supreme-court-to-shut-down-on-yom-kippur.