The 1966 Orioles: More than Frank Robinson

This article was written by David W. Smith

This article was published in The National Pastime: A Bird’s-Eye View of Baltimore (2020)

The 1966 season was the culmination of several good seasons for the Orioles, a pattern that began with the 1960 team and the famous “Kiddie Corps” that made an unexpected great run at the AL pennant. From 1961 through 1965, they finished 3rd, 7th, 4th, 3rd, and 3rd — a solid run after the first dismal seasons following the 1954 transfer from their previous reality as the St. Louis Browns. During this six-year stretch they won over 90 games 3 times and 89 on another occasion for a total of 538 wins and a winning average of .558. Only the White Sox and Yankees had higher winning averages over that period. In addition to the surprising second-place finish in 1960, they were only two games out (but in third place) in 1964, a pennant race that was very close all season.

The 1966 season was the culmination of several good seasons for the Orioles, a pattern that began with the 1960 team and the famous “Kiddie Corps” that made an unexpected great run at the AL pennant. From 1961 through 1965, they finished 3rd, 7th, 4th, 3rd, and 3rd — a solid run after the first dismal seasons following the 1954 transfer from their previous reality as the St. Louis Browns. During this six-year stretch they won over 90 games 3 times and 89 on another occasion for a total of 538 wins and a winning average of .558. Only the White Sox and Yankees had higher winning averages over that period. In addition to the surprising second-place finish in 1960, they were only two games out (but in third place) in 1964, a pennant race that was very close all season.

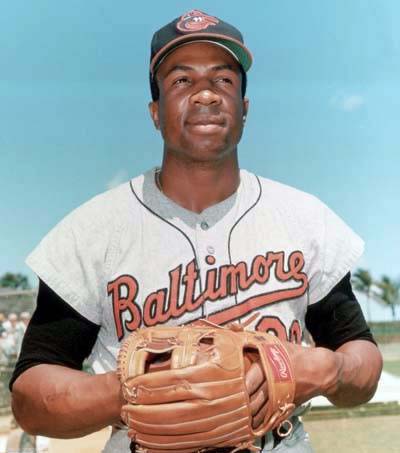

The player who probably comes to mind first in discussions of the 1966 Orioles is Frank Robinson. He was acquired from Cincinnati in December 1965 for Milt Pappas and two others. Despite Reds owner Bill DeWitt describing him as “not a young 30,” Robinson had an exceptional first year in the American League, winning the 1966 Triple Crown (.316, 49 home runs, 122 RBIs), the first to complete the feat since Mickey Mantle in 1956. At season’s end he was voted the Most Valuable Player in the American League, the first — and still the only — player to win the MVP in both leagues. He would also be named the Most Valuable Player in the 1966 World Series.1 But it takes a complete roster to have the success that the 1966 Orioles did, and the other 33 Birds were much more than mere bit players. This article will discuss many players’ contributions and the collective accomplishments of the team.

The team was largely built from within, augmented by a few key acquisitions over several years. Eighteen members of the 1966 team started their major-league careers with Baltimore, including Steve Barber, Sam Bowens, Wally Bunker, Andy Etchebarren, Davey Johnson, Dave McNally, Jim Palmer, Boog Powell, Brooks Robinson, and Eddie Watt. Other stalwarts arrived in Charm City from other teams 1961–63: Luis Aparicio from the White Sox in a 1963 trade; Paul Blair from the Mets in the 1962 first-year player draft, Curt Blefary from the Yankees as a 1963 first-year waiver choice, and Stu Miller and Russ Snyder in trades with the Giants (1962) and Athletics (1961).

There were minimal changes to the team from 1965 to 1966 with only two significant modifications. In addition to the advent of Frank Robinson, 20-year old Jim Palmer became a regular part of the rotation with 30 starts after six in his rookie season the year before, taking up most of the work done in 1965 by the departed Pappas. Very few other players who had significant playing time in 1965 left after that season, all veterans: outfielder Jackie Brandt, first baseman Norm Siebern, and pitcher Robin Roberts.

Upon becoming a regular in 1960, Brooks Robinson was the first major Orioles fan favorite, and is arguably the greatest third baseman of all time.2 He played over 140 games at third base for each of the next 16 years, winning the Gold Glove all 16 seasons. He was on the AL All-Star team 15 of those years, winning the AL Most Valuable Player award in 1964, the All-Star game MVP in 1966, and the World Series MVP in 1970 when he dazzled the nation with his extraordinary fielding (ask Lee May!), batting .429 with two doubles and two home runs among his nine hits. In his first World Series at bat in 1966, in the first inning of game one in Los Angeles he homered off Don Drysdale of the Dodgers. The Orioles scored three times and set a definitive tone for the dramatic four-game sweep. He was the anchor of the franchise before Frank Robinson arrived and after Frank departed.

Boog Powell was the second home-grown player to become a fixture for the team. Signed when he was 17, Boog progressed quickly through the Orioles minor league system, becoming the team’s regular left fielder in 1962 at the age of 20. Although he is best remembered as a first baseman, in his first three seasons after his 1961 cup of coffee, Powell appeared in 356 games in left field and only 29 at first. The presence of Frank Robinson stabilized the outfield composition, enabling Boog’s permanent move to first base in 1966.3 This was a significant step for the Orioles as they established their core lineup for years to come. Powell’s 34 home runs in 1966 were third in the AL, trailing only Frank Robinson’s 49 and the 39 mashed by Harmon Killebrew of the Twins.

Luis Aparicio became the regular shortstop immediately upon his arrival in Baltimore in 1963, playing over 140 games there each season through 1965. The win-win trade which brought him from Chicago involved six players, with Aparicio and fellow future Hall-of Famer Hoyt Wilhelm the marquee names.4 Before he took over the position, time at shortstop had been split between serviceable infielders Jerry Adair and Ron Hansen. With Brooks Robinson to Aparicio’s right, the Orioles had a Hall-of-Fame left side of the infield from 1963 through 1967 as Luis won a pair of Gold Gloves along with Brooks. He also provided most of the speed for the Orioles, with over 50% of the team’s stolen bases 1963–65 (123 of 242), including 40 of the team’s 97 in 1963 when he made the AL All-Star team. His 57 steals in 1964 are still the single season record for the current Orioles.

Davey Johnson played briefly for the Orioles in the early part of 1965 before returning to the minors for more seasoning. Upon his return in 1966, he became the regular second baseman for seven seasons, playing in two All-Star games and winning three Gold Gloves. With Powell and Johnson in place, the Baltimore infield was anchored for many years. Johnson has the interesting distinction of being the last man to have a base hit against Sandy Koufax, collecting a single in the sixth inning of Game Two of the 1966 World Series. Following his playing career, Johnson became a very successful major league manager, compiling a winning average of .562 while at the helm of five different teams, including a two-year stretch with the Orioles in 1996 and 1997, when he guided them to second and first place finishes, the latter earning him the first of his two Manager of the Year awards.

As mentioned above, the arrival of Frank Robinson stabilized the outfield with Robinson playing 151 games and three others, Paul Blair, Curt Blefary (AL rookie of the year in 1965) and Russ Snyder each playing over 100 games. Blefary (23 home runs) and Snyder (batting average .306) made significant offensive contributions as well. Sam Bowens appeared in 68 games, playing all three outfield positions.

The Orioles were a very stable team in terms of starting lineups with only 44 different lineups of 8 position players. (By comparison, the average for the 1966 AL was 66 different “Starting 8’s” — the most being 87 by the White Sox.) Seven Orioles each started more than 100 games at the same position: Luis Aparicio, Curt Blefary, Andy Etchebarren, Davey Johnson, Boog Powell, Brooks Robinson, and Frank Robinson. The only other AL team that had seven men start 100 games each in one spot was the Red Sox. The team with the fewest was the Yankees, who had only two. Frank Robinson’s arrival stabilized positions throughout the field. Not only did he start 132 games in right field (19 in left), but the other outfield positions were much less variable, with the most dramatic change being the Boog Powell move as mentioned above.

After two brief stints in 1962 and 1965, Andy Etchebarren became the Orioles regular catcher in 1966, starting 118 games. His offensive production was modest, but he did hit 11 home runs with 50 RBIs. On the defensive side, he was effective at throwing out would-be base stealers, doing so at a 39% rate both for 1966 and for his career. He played for the Orioles through mid-1975 when he was sold to the Angels. During those years, 1967 was the only other time that he caught 100 games in a single season. After his playing career ended, Etchebarren was a coach for the Angels, Brewers, and Orioles.

The pitching for the 1966 team was good, but not spectacular, finishing fourth in ERA with a team value of 3.32; the league average was 3.44. Manager Hank Bauer used 11 different starting pitchers, with two having 30 or more starts, two others with more than 20 or and two with more than 10. These six men had 138 starts in the Orioles’ 160 games with 20 of their 23 complete games. That complete game total was next to last in the league, surpassing only the Kansas City Athletics. Their great pitching strength was the bullpen. The starters had a collective ERA of 3.50, but relievers combined for 2.98, a close third to Minnesota (2.93) and Chicago (2.55). Stu Miller led the way with an ERA of 2.25 in 51 appearances. Eddie Fisher relieved in 44 games with an ERA of 2.64. The other two main figures from the bullpen were Moe Drabowsky (41 relief games with 2.71 ERA, ,plus three starts) and Eddie Watt (30 relief appearances with 3.56 ERA, and 13 starts).

The starters were a combined 58-47 while the bullpen compiled a record of 39-16 with 51 saves. This is somewhat startling given the tremendous and highly visible accomplishments of the starters in the World Series in which they had three consecutive complete game shutouts in games two through four. Jim Palmer led the starters with 15 wins, Dave McNally had 13, Steve Barber 10, and Wally Bunker 10. The Orioles had 14 different pitchers with at least one win, showing a very diverse and balanced staff working under the tutelage of pitching coach Harry Brecheen.

The offense led the way for the 1966 Orioles as shown by WAR (Wins Above Replacement). The team led the AL with 13.6 WAR, well ahead of the Twins with 8.3. Within that 13.6 WAR, the Baltimore lineup accumulated 11.5, easily leading the AL over next-best Detroit (6.4) and trailing only the Pirates (15.2). Baltimore pitchers had a collective WAR of 2.1, fourth in the AL and well behind the major league-leading Dodgers (14.6). The offense of the Orioles was outstanding in every way, leading the AL in runs scored, batting average, on-base average and slugging average. They were the only AL team to lead in all these categories between 1954 (Yankees) and 1975 (Red Sox). Their 179 home runs were second to Detroit by four.

This production translated to success throughout the season, as they were in first place for 130 of 170 days. Their low point came on May 28 when they trailed Cleveland by 4.5 games. They then won 12 of their next 16, moving back into first place on June 7 and not relinquishing the top spot for the rest of the year, eventually winning by nine games over the Twins.

Overall, the 1966 Orioles were a young team. Five of their nine Opening Day starters were under 25 and only Aparicio and Frank Robinson were older than 29, at 31 and 30, respectively. This youth likely contributed to their very low number of injuries during that championship season, without any long stints on the disabled list — although pitchers Barber, Bunker, and Palmer did miss a few starts due to arm problems.

No discussion of the 1966 Orioles would be complete without mentioning the manager, Hank Bauer. Hank had a solid career with the Yankees, appearing in nine World Series in his 11 full years with the Bombers. He was widely regarded as tough as nails, based in part on record as a Marine in WWII, during which he won two Bronze Stars and two Purple Hearts. It is perhaps surprising that someone with such a rugged background was not an unfeeling tyrant with his players. He was relaxed with his young team and they respected him for it. Bauer praised Frank Robinson for having a positive effect on the “young players just by talking to them…”

Even as Frank Robinson was exciting Baltimore fans and becoming hugely popular, he and his family had some rough times off the field as they encountered the starkly segregated housing market in Baltimore. He had not been active in civil rights issues before this, but became more outspoken when the Orioles did not support his efforts to overcome the bigotry of the city’s real estate business.5 This was a turbulent time in American society as the Civil Rights Act (1964) and Voting Rights Act (1965) were still new and both engendered stiff opposition. The Vietnam War was also escalating rapidly with the authorized troop level in the Southeast Asian conflict rising to just under 400,000 in 1966.

The 1966 season was also a significant transitional year for baseball as the institution underwent profound changes at the same time as the social upheaval in the country at large. The two most dominant teams since the end of World War II were the Yankees and the Dodgers. The Yankees’ incredible run of 15 pennants in 18 seasons ended in 1964 and they hit rock bottom in 1966, finishing last, and they languished for most of the next decade. The gap left by the Yankees was filled by a several teams, but the most successful was the Orioles, who won over 100 games in three straight seasons (1969–71).6

In retrospect it is clear that the Orioles had been building and improving for several years, positioning them ideally to fill the vacuum left by the Yankees. The addition of Frank Robinson was the deciding action that put them over the top to become champions, but it was not a one-man effort; the rest of the team was much more than a supporting cast. The team had four men elected to the Hall of Fame: Brooks and Frank Robinson, Palmer, and Aparicio. Their unexpected World Series sweep of the Dodgers in four games showed how solid they were. It was the most dominating World Series performance in history: The Dodgers scored a total of two runs in the four games and none at all in the last 33 innings, as they were shut out the last three games. The 1966 Orioles had established themselves dramatically for all the baseball world to see.

DAVID W. SMITH joined SABR in 1977 and in 2005 he received SABR’s highest honor, the Bob Davids Award. In 2012 he was honored with the Henry Chadwick Award. He is a past co-chair of the Statistical Analysis Committee and the recipient of the first SABR Special Achievement award. He is also the founder and president of Retrosheet, a non-profit organization dedicated to the collection, computerization, and free distribution of play-by-play accounts of major league games. He is an Emeritus Professor of Biology at the University of Delaware.

Sources

The SABR biographies of Frank Robinson (by Maxwell Kates) and Hank Bauer (by Warren Corbett) were extremely valuable.

The WAR values are from Baseball-Reference.com..

All other statistical data are from Retrosheet (https://www.retrosheet.org/).

Notes

1 Frank Robinson was also rookie of the year in 1956. He became manager of four different teams including the Orioles and won the 1989 Manager of the Year Award for leading the Birds to an exciting second-place finish, an unexpected comeback from the 1988 season in which the team began the season 0-21. As a player-manager of the Indians in 1975, he became the first African-American to hold a major-league managerial post.

2 Brooks Robinson was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1983, his first year of eligibility.

3 Jim Gentile had been firmly entrenched at first base 1960–63 after arriving from Los Angeles. Gentile was traded after the 1963 season to Kansas City for Norm Siebern who was the regular first baseman for the Orioles in 1964 (149 games). The 1965 season began with Siebern at first until mid-June when Powell moved in from the outfield. Boog would play much more at first than the outfield for the rest of the year.

4 Aparicio was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1984.

5 “Frank Robinson,” Black History in America website. Accessed July 6, 2020: http://www.myblackhistory.net/Frank_Robinson.htm.

6 In the NL, a similar pattern occurred with the Dodgers. Although they won the 1966 NL pennant, it was the end of the Brooklyn influence, as only Koufax, Drysdale, Jim Gilliam, and John Roseboro remained from their East coast incarnation. They were a weak team for nearly a decade after.