The Babe’s Canadian Connections

This article was written by David McDonald

This article was published in The Babe (2019)

“Something about Canada seemed to agree with him … on an intriguing psychological level. He spent years telling people all sorts of odd fibs about his supposed Canadian connections.” — David Giddens, CBC Sports1

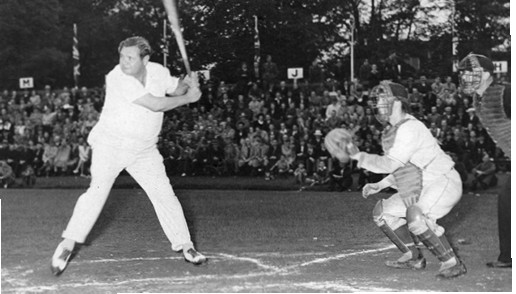

In support of the Canadian war effort, Ruth flew to Halifax, Nova Scotia, in the summer of 1942 to take part in the opening of the Royal Canadian Navy’s Wanderers Grounds recreational facility. (Courtesy of David McDonald.)

Given that he was a notoriously unreliable witness to his own life, the inconsistencies and the discrepancies in the Babe’s telling of it are hardly surprising. While some of the purported connections between Ruth and Canada don’t pan out, the country was a recurring setting and its people enthusiastic supporting players in the Babe Ruth story. Here are some of the highlights:

1902. Dispatched to St. Mary’s Industrial School for Orphans, Delinquent, Incorrigible and Wayward Boys, in his native Baltimore, 7-year-old George Herman Ruth Jr. was taken under the wing of the school’s hulking assistant athletic director and prefect of discipline, the Xaverian layman Brother Matthias.

Matthias’s real name was Martin Boutilier,2 and he had come to Baltimore from the coal-mining town of Lingan, on Nova Scotia’s Cape Breton Island.

Ruth later described Matthias as “the father I needed”3 and “the greatest man I’ve ever known.”4 It was the 6-foot-4, 225-pound Cape Bretoner (some sources list him at 6-feet-6 and up to 300 pounds) who mesmerized the young Ruth with his ability to hit towering fungoes during practices. “I think I was born as a hitter the first day I ever saw him hit a baseball,” Babe said.5

July 9, 1914. Boston Red Sox owner Joe Lannin acquired Ruth, along with fellow pitcher Ernie Shore and catcher Ben Egan, from cash-strapped Baltimore Orioles owner Jack Dunn for a reported $25,000.

Lannin, from Lac-Beauport, Quebec, was a character from the pages of a Horatio Alger novel. Orphaned in his early teens, he set out to seek his fortune in the United States. Arriving in Boston in 1880 – legend has it, on foot – Lannin started out as a bellhop. Eventually he made a small fortune in commodities and real estate. In 1913 he bought a 50 percent share in the Red Sox.

Lannin’s teams won World Series in 1915 and 1916. But the pressures of baseball, even winning baseball, proved overwhelming for the transplanted Quebecker. “I am too much of a fan to be an owner and it was interfering with my health,” he told the New York Times.6 In 1917 he sold his interest in the club to Harry Frazee, later vilified as the man who sold Ruth to the Yankees. Lannin is a member of the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame.

July 11, 1914. Nineteen-year-old Babe Ruth’s first day in Boston was an eventful one. In the morning, by most accounts, he stopped for breakfast at a diner called Landers Coffee Shop and took a fancy to a young waitress, Helen Woodford. In the afternoon, he started his first major-league game, where the first batter he faced was Cleveland Naps left fielder Jack Graney. Graney, from St. Thomas, Ontario, singled but Ruth recovered to pitch seven solid innings in a 4-3 win.

Graney played his entire 14-year career with Cleveland. In 1932 he became the first ex-major leaguer to become a play-by-play announcer, as the radio voice of the Indians. He is a member of the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame.

September 5, 1914. Sent down to the International League Providence Grays, Ruth threw a one-hit shutout and hit his first – and only – minor-league home run. It was a three-run shot and came in the sixth inning of a 9-0 victory over the Maple Leafs at Hanlan’s Point Stadium in Toronto.

October 17, 1914. After a courtship of less than two months, Ruth, 19, married his favorite waitress, Helen Woodford. Press reports variously stated they had married in Providence, Rhode Island, or in Boston. To add to the confusion, Babe would tell some people that Helen (like Brother Matthias) was a Nova Scotian, while, on her marriage-license application, Helen herself claimed to be from Galveston, Texas. By the time of Babe’s first passport application, in 1920, Galveston would morph into El Paso. None of this was true.

The uncertainty about Helen’s origins and the location of their wedding probably began as a subterfuge to obscure the fact she was still a few days shy of her 18th birthday when they got hitched. The facts are these: Helen was born Mary Ellen Woodford in Boston on October 20, 1896. (Why she and Babe wouldn’t have waited another three days to marry legally remains a mystery.) Helen was the third of nine children of Michael and Johanna Woodford, immigrants, not from Nova Scotia as is sometimes stated, but from Newfoundland.7 And Babe and Helen were married in Ellicott City, Maryland – or, as Ruth would later remember on Grantland Rice’s radio show, in a place called “Elkton.”8

October 1923. Ruth and pitcher Herb Pennock celebrated the Yankees’ first World Series win with a hunting trip to “the big-game territory of the Miramichi, New Brunswick, where the moose run wild.”9 Oddly, their choice of a hunting companion was coach Hughie Jennings of the Series-losing Giants.

October 20, 1925. An ailing Babe, still struggling to bounce back from “the bellyache heard ’round the world,”10 returned to New Brunswick on another moose-hunting expedition, this time in the company of fellow ballplayers Bob Shawkey, Eddie Collins, Joe Bush, Muddy Ruel, and Benny Bengough. Their camp, on the Tobique River in the northwest of the province, was located 40 miles deep into the bush. Babe managed the first 15 miles of the trek on foot but finished it on horseback.

Three weeks later, according to Shawkey, a revitalized Ruth hiked the entire 40 miles back to the nearest railway station without a word of complaint. Nevertheless, when Babe reported to a New York gym in early December, he tipped the scales at 254 pounds. His trainer, Artie McGovern, melodramatically pronounced Babe “as near to being a total loss as any patient I have ever had under my care,”11 thereby setting the stage for a demonstration of his own miraculous abilities as a fitness guru.

October 17, 1926. A week after losing the Series to Pete Alexander and the St. Louis Cardinals, Ruth, along with Yankees teammate Urban Shocker, popped up in Montreal on the fourth stop of a postseason barnstorming tour. Babe was guaranteed a minimum of $3,000 for a cold, gray afternoon’s work. He did not disappoint.

Suiting up for Guybourg against Montreal City League rival Beaurivage. Babe belted two home runs. The first came off Shocker, while the second, a game-winning rocket off Chicago White Sox prospect Paddy Galkin, reportedly traveled more than 600 feet. The blow came just five days after another Bunyanesque blast, one estimated by witnesses at Artillery Park in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, to have traveled 650 feet.

When a pregame slugging exhibition was added in, the Montreal moonshot became the Babe’s 36th dinger of the day, and it brought the festivities to a sudden halt “because the management had no more spheres.”12 Ruth, with three innings of hitless relief, was also the winning pitcher.

November 1926. Ruth headlined for a week at the Pantages Theater in Vancouver, British Columbia, on a bill touted as the “The King of Swat and five other big acts.”13 The B.C. appearance was one stop on a highly lucrative vaudeville tour, for which the Babe took in “a cool 100,000 smacks for 12 weeks of cavorting before Alex’s footlights.”14 It was almost twice Ruth’s annual baseball salary and, on a weekly basis, eclipsed the earnings of vaudeville’s biggest stars, including W.C. Fields, Al Jolson, and Fanny Brice.

The 20-minute “act,” repeated four times a day, began with some film clips of the Babe in action, followed by a few jokes, a fictionalized and highly sanitized rendition of his life story, a swing demonstration, and an on-stage autograph session. Later on the tour, teammate Mark Koenig would pronounce Ruth’s set “boring as hell.”15 Vancouver audiences were too spellbound to notice.16

October 1928. Ruth and Lou Gehrig brought their Bustin’ Babes and Larrupin’ Lous postseason tour to Montreal and Ottawa-Hull. (See the accompanying article, “The Babe Comes North.”)

October 19, 1934. Ruth, then 39 and soon to be an ex-Yankee, returned to Vancouver as the star attraction of Connie Mack’s All-Americans. The squad, featuring seven future Hall of Famers and polyglot backup catcher and future spy Moe Berg, was en route to Japan for a 16-game postseason tour.

In Vancouver, they were slated to play against a local semipro club, but with the rain pounding down, the players anticipated a relaxing evening. The Babe was even photographed in his hotel suite wearing striped pajamas and a garish bathrobe, smoking his pipe and digesting a roast-duck dinner. But when word reached the hotel that 3,000 fans were arriving at the ballpark demanding to see their idols in action, Ruth reportedly rallied the troops. “If these people can take the weather, so can we,” he said. “We’re gonna give ’em a ball game.”17

Ruth and company headed to the field, the outfield of which was described as a “rice paddy,”18 the infield “a mud pit.”19Gehrig appeared on field wearing rubber boots and holding an umbrella. But when the umpires tried to call the game after six innings, Ruth insisted on playing it to a soggy conclusion. The teams played to a 2-2 tie. The next day Babe and the All-Americans boarded the Canadian Pacific liner Empress of Japanfor the 12-day voyage to Yokohama.

April 16, 1935. George “Twinkletoes” Selkirk, a native of Huntsville, Ontario, took over the most challenging position in baseball – post-Ruth right field in Yankee Stadium on Opening Day. Adding to the pressure, Selkirk took the field wearing Babe’s iconic number 3 and batting in his old number 3 slot in the Yankees order. Still, he managed one of only two Yankee safeties in a 1-0 loss to Wes Ferrell and the Red Sox.

Over the next eight seasons, Twinkletoes would run up numbers that, while hardly Ruthian, were nevertheless fairly impressive. For his career, he batted .290/.400/.483 with a 127 OPS+ and 108 home runs. He won five World Series and appeared in two All-Star Games. Selkirk is another member of the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame.

July 1936. Ruth, recently inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s inaugural class, visited the coal town of Westville, Nova Scotia, at the invitation of a local doctor he had met in New York. It was one of many post-retirement trips Babe made to the home province of his mentor, Brother Matthias.

Prior to a ballgame featuring the hometown Miners, the Babe took a few cuts and swatted a ball over the center-field fence. He also spent some time salmon fishing in the St. Mary’s River, playing golf in Halifax, Digby, and Pictou, and knocking back a few crustaceans at the Pictou County Lobster Festival.

October 1937. Ruth’s fall hunting trip to Nova Scotia was documented in Outdoor Life magazine: “He is a snapshooter, as quick as lightning, and he can drill a tomato can at 60 yards.”20

Back in New York, Babe rolled off the ship from Yarmouth in his Stutz Bearcat, three deer carcasses strapped to the fenders and a 250-pound black bear slumped in the rumble seat. His next stop was a charity golf match on Long Island before 10,000 spectators.

August 1, 1942. Ruth flew to wartime Nova Scotia and appeared at the opening of a Royal Canadian Navy recreation complex in Halifax. A game between local seamen and personnel stationed in Toronto was interrupted so Babe could put on a hitting display. Local legend had it he homered on every swing. In truth, Ruth, now 47 and wearing street shoes and a cream-colored suit, failed to knock a single ball out of the park. The 5,000 in attendance had to be satisfied with the dozen or so autographed baseballs Babe tossed into the crowd. One is still in the collection of the Nova Scotia Sport Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 David Giddens, “Babe Ruth; Made in Canada?” cbc.ca/sportslongform/entry/babe-ruth-made-in-canada, June 13, 2017.

2 A number of Ruth chroniclers, including Leigh Montville, Marty Appel, Allan Wood, and Wilborn Hampton, give Matthias’s birth name as “Boutlier,” but in his home county, the name is invariably Boutilier. According to Nova Scotia Vital Records, 1763-1957, Martin Boutilier was born in Bridgeport, Nova Scotia, on July 11, 1872.

3 Paul MacDougall, “The Man Who Inspired the Babe,” Cape Breton Post, August 22, 2014.

4 Robert Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (New York: Fireside Books, 1992), 37.

5 Creamer, 35.

6 Quoted by David L. Fleitz, The Irish in Baseball: An Early History. (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland and Company, 2009), 176.

7 Newfoundland didn’t become a province of Canada until 1949. In Michael and Johanna Woodford’s day it was a British colony.

8 Fred Shoken, “Babe Ruth’s Marriage to Helen Woodford,” familysearch.org/photos/artifacts/24940973?p=9153286&returnLabel=Mary%20E%20(Helen)%20Woodford%20(K8TQ-WMX)&returnUrl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.familysearch.org%2Ftree%2Fperson%2Fmemories%2FK8TQ-WMX.

9 “20 Yankees Each Receive $6,160.46,” New York Times, October 17, 1923: 6.

10 A popular take on W.O. McGeehan’s original line: “It is not remarkable that the stomach ache of Babe Ruth was heard around the world.” From “A Demigod Has Indigestion,” New York Herald Tribune, April 11, 1925.

11 Quoted by Leigh Montville, The Big Bam: The Life and Times of Babe Ruth (New York: Doubleday, 2006), 218.

12 “Ruth, By Losing 36 Baseballs, Breaks Up Game in Montreal,” New York Times, October 18, 1926: 27.

13 Advertisement, Vancouver Morning Star, November 30, 1926.

14 Vancouver Sun, November 29, 1926. Quoted by John Mackie, “This Day in History,” Vancouver Sun, November 29, 2012. “Alex” is vaudeville impresario Alexander Pantages.

15 Quoted by Harvey Frommer, Five O’Clock Lightning: Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and the Greatest Baseball Team in History, the 1927 New York Yankees (Lanham, Maryland: Taylor Trade Publishing, 2008), 12.

16 “His every word and action riveted the attention of all and the big fellow, who is baseball’s greatest star, pleased the folks equally as much as his four ply clouts satisfy the fans who throng in thousands to watch him work on the diamond. Babe bats 1.000 in the footlight personality league and his 20-minute act is all too short.” “Babe ‘Scores’ at Pantages,” Vancouver Sun, November 30, 1926.

17 Tom Hawthorn, “The Day Babe Ruth Played in Vancouver’s Rain,” The Tyee, October 21, 2014. thetyee.ca/News/2014/10/21/Babe-Ruth-Played-in-Vancouver/.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Bob Edge, “Babe’s in the Woods,” Outdoor Life, March 1938.