The Day Babe Ruth Came to Sing Sing

This article was written by Gary Sarnoff

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Big Apple (New York, 2017)

On September 5, 1929, Babe Ruth and the New York Yankees played an exhibition game against the Mutual Welfare League team inside the walls of Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Ossining, New York.

“I hear we’re going to Sing Sing next Thursday,” Yankees catcher Ben Bengough announced in the Yankee Stadium dugout.

“I hear we’re going to Sing Sing next Thursday,” Yankees catcher Ben Bengough announced in the Yankee Stadium dugout.

“Yeh,”said Babe Ruth, “It’s a good thing we ain’t going to play in a bughouse. They may keep some of you birds there.”1

The Yankees are coming! The news spread through the penitentiary like wildfire, and the inmates began counting down the days until the Bambino and his teammates would appear. The exhibition game would be against the penitentiary’s top team, the Ossining Orioles of the Mutual Welfare League. The Yankees wouldn’t be the first major league team to play on the sunbaked skin surface of Sing Sing Stadium. The New York Giants had made six appearances during the 1920s, with their most recent visit occurring nine days before the Yankees were scheduled.

The idea to bring big league teams to Sing Sing evolved from Warden Lewis E. Lawes’s theory of rehabilitating prisoners through building morale rather than hammering discipline. When appointed as warden of Sing Sing by New York governor Alfred Smith in 1919, Lawes arrived with a goal to focus on building the inmates’ morale through recreation, athletics, work, books, and medical treatment. Under his tenure, sports and recreation became a big deal at Sing Sing, with not only inmate baseball but an annual field day consisting of track and field events, handball, bocce, and other recreational games.

On September 5, 1929, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and many of the players on the Yankees roster journeyed to the prison. Tall stone walls that impounded the buildings located on the bank of the Hudson River in the town of Ossining, 28 miles north of Yankee Stadium. Not attending the day’s event were Tony Lazzeri, Bob Meusel, Leo Durocher, some of the pitchers, and manager Miller Huggins, who was said to be very ill and in need of a day off. (Little did anyone realize how sick the New York skipper really was, and that he was within a month of living the final day of his life.)

When the big iron-plated front door was opened, a security guard carefully counted each player passing through the gate. The team was escorted through several barred gates—some plain, some fancy—toward the jail’s cells to begin their tour. From the corridor to the cellblocks, the players got a glimpse of the officers’ mess. Ruth decided to step inside and snatch a slice of gingerbread resting on a plate.

Inmates were star-struck by the sight of the Bambino, who was well-dressed for the occasion in spotless golf togs: white shirt, black tie, white knickers pleated in black, with black stockings and black and white shoes. When the prisoners said hello, Ruth responded with a smile, a salute, or by answering with his familiar “hello, kid.”2 One of the temporary residents, too ill to attend the game that day, asked Ruth to sign his cell wall, which Ruth gladly did.

The Yankees noted that the prisoners were uniformed in dark gray pants, white shirts or sleeveless white undershirts and black shoes, the fashion for jailbirds since striped suits and pillbox hats went out of vogue. The defending American League champs were amazed over how young looking and pleasant-faced the inmates appeared. They seemed happy, content, healthy, and were tan from their daily outdoors jobs and recreational activities, which was also noted by the Giants during their recent tour “These guys look like they’d just come back from a month on the beach,” one of the Giants had said. “Where is that parlor I’ve read about?” another player kidded.3

The next phase of the tour took the players to the new cells built into the hill on the grounds, described as “ritzy,”4 with each new cell furnished with radio headphones. The Yankees also saw the correctional facility’s new auditorium in the process of being equipped with machinery to show motion pictures with sound.At this juncture of the tour, prison life looked as if it may not be so bad. However, the next part of the journey would be “a somewhat gruesome reminder of prison life.”5

Although Warden Lawes had always bitterly opposed the death penalty, the law existed in New York, and in order to comply, Sing Sing had a Death Row. The tour guide conducted the Yankees to the death chamber, furnished with a big wooden electric chair mounted to the floor. Ruth sat in the big chair, which seemed “to sober him for the next half hour,” according to New York Evening Journal sportswriter Ford Frick. 6

While on their way through the prison yard following their exit from the death house, the Yankees came across an elderly blind inmate on his way to a workshop. The tour paused while Ruth assisted the elderly prisoner through the yard and to a workshop entrance. “There’s a nice chap,” Ruth said when he rejoined his teammates. “I wonder what he did? Stole something, I suppose. He’s too gentle to do any rough stuff.”

“Up to a short time ago that old fellow was in the death house awaiting execution,” the tour guide informed Ruth. “He murdered his wife and was sentenced to die. Now that he lost his sight, his sentence has been commuted to life imprisonment.” Surprised to hear this, Ruth looked down as he shook his head. “Gosh,” he said. “Gosh.”7

The Yankees then met the man in charge, Lewis E. Lawes, the distinguished forty-five year-old head official of Sing Sing who had started his career as a prison guard and had earned the utmost respect while working his way to the top. The warden hosted a luncheon for the players, and then it was finally time to play ball.

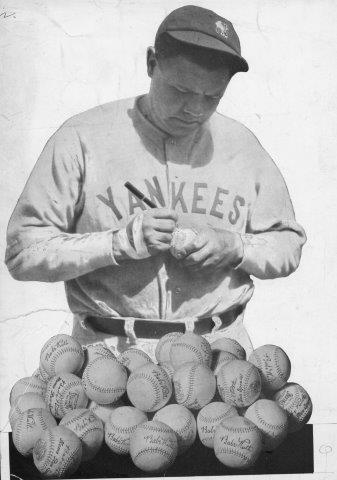

The Yankees were guided to the dressing room where once again they were carefully counted. After putting on their famous pinstriped uniforms with numbers on the jersey backs, they were again counted before being directed to the playing field. The minute the players appeared on the field they were confronted by the inmates for autographs. As one would expect, Ruth received the majority of autograph requests, and as usual, the Bambino obliged by signing and signing. “I didn’t know that there were so many of you here,” Ruth said with a laugh after he had signed the first fifty or sixty baseballs.8 After twenty minutes of autograph-seeking, the guards cleared the field in order to give the Yankees time to warm up before the game.

The high walls that encompassed the entire facility also served as the outfield wall. “Those gray walls are twice as insurmountable when you’re on the inside,” wrote Frick.9 Though the distance from home plate to the outfield walls is unknown, it was said that it didn’t take a wallop to clear the left-field wall. Only once in Sing Sing Stadium history had a ball topped the right field wall, hit by Bill Terry during a Giants’ visit in 1924. Never had a home run traveled beyond the center-field wall, although a drive of Ruthian proportions was thought possible to manage it.

Above the towering walls were six watchmen with machine guns, stationed in three towers, unresponsive and uninterested in the score yet closely monitoring the ballgames. Among the armed watchmen was a former major leaguer, William Leith, who had played for the 1899 Washington Senators and had spent time with the New York Giants after Dan Brouthers had highly recommended him. Now in his tenth year as a guard at Sing Sing and wearing a cap bearing the letters “N.Y.S.P.” Leith insisted that the Giants and Yankees were lucky that they did not have to play the best at Sing Sing. According to Leith the most talented team was the all-colored team of the institution’s Shop League. “The really classy team of the institution, better than the official nine representing the Mutual Welfare League,” insisted Leith. 10

Down the left-field foul line were covered bleachers that the inmates occupied. For the Yankees game, all spots on the benches were taken. Inmates unable to fit in the seating area sat atop the bleacher’s cover, in front of the stands, and on the field along the left-field wall.

The right-field bleachers were reserved for outside spectators. Because this was no average ballpark, there were rules for these fans, one requiring that they arrive prior to game time. When it was time to enter, a gate was opened: the only way to or from these bleachers. These stands were backed by a wall and in front stood a wire screen. All spectators were admitted at the same time and only at that time. Late arrivals were not admitted and nobody was permitted to leave until the game was finished. There were no vendors, no concession or souvenir stands. There were also no tickets or charge for admission. However, during the game an optional donation was taken up among the crowd for funds to buy equipment, mitts, and baseballs for the Mutual Welfare League.

Behind home plate a cozy suite was elevated above the field, used by Warden Lawes and the press. Inside the box were cushioned seats, photos of Abraham Lincoln, Charles Lindbergh, and movie stars, plus a window with a view of the Hudson.

The Mutual Welfare League team entered this game with a season record of 32-6, but it didn’t count for much. They were not in a league, were not battling for a pennant, nor were they motivated to win one for old dear Sing Sing. The team never left the prison. They had no road games. All games were at home, usually played on Saturdays or Sundays against visiting amateur ball teams. There were few privileges in playing for the Mutual Welfare League, other than getting to play the great game of baseball and receiving an extra meal on game day. The players were also entitled to an early leave from their daily jobs at workshops in order to practice from 4:00 to 7:00. They did not get paid for playing. They earned the same 1½ cents per day that the other inmates earned for laboring in the workshops.

The best team in the Mutual Welfare League, decked out in castoff New York Giants gray road uniforms, took the field for the top of the first. Pitching for the inmates was Charlie McCann, who had earned a reputation as a hitter the week before by clouting one out of the yard off of Giants pitcher Joe Genewich. The team’s best pitcher, William Conklin, would appear later in the game. Known by his nickname, “Red,” Conklin had once played semi-pro baseball for $75-85 per week.11 He was paroled in 1922, but by the end of that season he was returned to Sing Sing in handcuffs when charged with disorderly conduct.12 Because Conklin had violated Baumes Law by committing more than three felonies, he was automatically sentenced for life. His only hope for release was a pardon by the state.

The manager of the Mutual Welfare League team was the team’s third baseman, Mike Lawlor, in for ten to twenty and hoping to be pardoned while he still was young enough to play professionally. At first base was another inmate named Mike, a resident for so long that it was said he was almost happy to be there. He had arrived fifteen years ago as a kid and still had ten years to go on his sentence.13 Old and grizzled, he was still counting on a career in professional baseball. “By the time I’m out of here I’ll be able to play first base like nobody’s business.”14 Another Mike was the megaphone announcer, said to be a handsome fellow with a pleasant smile who kept announcing that he would be a free man in twenty-two days, “And when I get out the big gate I won’t ever come back here again. Not even to manage this club.”15

A former dentist now living in Sing Sing called the balls and strikes from behind the plate. “It’s better to have a dentist for an umpire rather than an umpire for a dentist,” quipped a sportswriter. The sportswriter noted that a dentist became an umpire because there were no umpires in Sing Sing, “Although one would think, after listening to the remarks made by baseball fans, the jails would be full of umpires.”16

Ruth smiled as he stepped in for his first at bat in the top of the first. There was a feeling that he would hit a home run—maybe two or more—on this day. He had already energized the prison populace by clearing the right field barrier during batting practice.

After hitting a hard grounder that rolled into the far distance of the outfield for a double in his first at bat, Ruth got hold of one in the top of the second and sent it for a long ride to center. The ball seemed to travel for miles and miles. “Gee! I wish I was riding out on that one,” said Mike, the first baseman of the Mutual Welfare League.17 The ball sailed past a watchtower and landed far beyond the center-field wall for the first home run hit over Sing Sing Stadium’s center-field barrier. Amazed by the power of the Bambino, even the watchmen in the towers put down their machine guns to applaud. From the warden’s box behind home plate, Warden Lawes, just as amazed as everyone else, stood up and cheered. When the ball landed outside the penitentiary, a mad scramble ensued among the children and village’s trustees who had camped outside hoping for such a prize.

Ruth took his familiar short, choppy home run trot, but as he headed toward second base, the Mutual Welfare League’s second baseman interrupted him with a plea to have his baseball signed. Ruth obliged.

One inning later, Ruth hit another one, this one topping the right-field wall to match Bill Terry’s feat. In the top of the fifth, he did it again, his third of the day, another drive to the right field that left the confines.

The game, unsurprisingly a rout in the Yankees’ favor, was said to “chiefly be a Yankees ball-signing exercise”18 rather than a ball game. Throughout the afternoon the inmates interrupted the game’s progress by hounding the Yankees for signatures. In the sixth inning, Yankees catcher Ben Bengough was standing on third base when he was approached for an autograph.

Ruth seemed to enjoy himself as much as anybody else, signing throughout the game and exchanging witticisms with the visiting fans while playing first base, his usual exhibition game position. In the bottom of the eighth, Ruth took the mound to pitch the last two innings. When the first batter stepped in, Ruth asked, “Can he hit a hook?” He threw a curveball, which the batter belted to left, but it curved foul. “He can,” confirmed Ruth. “I’ll try him on a fast one.” Before he went into his windup, an inmate left the bleachers and ran to the pitcher’s mound, where he pushed a baseball and pen toward Ruth. The Bambino removed his glove, tucked it under his arm, and signed. When play resumed, Ruth threw a fastball that the batter tagged for a single to center field. “I should have pitched him a knuckler,” said Ruth.19

In the bottom of the ninth an inmate named Clark tagged a Ruth pitch and sent it over the left-field wall. As Clark rounded the bases, Ruth shouted, “Hey! Are you eligible to sign a contract?”

He’s got one now,” said a voice from the bleachers occupied by the inmates. “He’s a ten year man, Babe.”20

When the game ended, the manual scoreboard operated by two inmates showed that the Yankees had won, 15–3. The scorebook kept by a trustee from a New York newspaper recorded a 17–3 Yankees win, “If that matters,” opted a sportswriter.21 When the last out was made the inmates immediately surrounded Ruth, forcing him to elbow his way to the dressing room.

Before entering the dressing room, the guards counted each Yankees player, and then they recounted when they had emerged. The guests were then escorted toward the exit. On the way, Ruth took one last look at the prisoners who were lined up and about to head back to their cells. “Goodbye, boys!” Ruth shouted. “And good luck!”

“Goodbye, Babe,” said Red Conklin. “Come again, any time. We’re always home.”22

GARY SARNOFF is a historian, a published author and a longtime SABR member. He was written articles for SABR’s BioProject and Games Project, Nats News, Minor League News, “Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game” and SABR’s 2009 edition of “The National Pastime.” In addition, he covered the Silver Spring-Takoma Thunderbolts of the Cal Ripken Sr. League from 2011-13, and has made several presentations about baseball, football, aviation and American History at historical societies and museums throughout the country.

NOTES

1 New York Sun, August 28, 1929.

2 New York Sun, September 6, 1929.

3 New York Herald Tribune, August 28, 1929.

4 Ibid.

5 New York Evening Journal, September 6, 1929.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 New York Herald Tribune, September 6, 1929.

9 New York Evening Journal, September 6, 1929.

10 New York Sun, August 27, 1929.

11 Rud Rennes, “Baseball Behind Bars,” New York Herald Tribune, September 8, 1929.

12 New York Times, March 19, 1923.

13 New York Evening Journal, September 6, 1929.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 New York Herald Tribune, September 8, 1929.

17 New York Evening Journal, September 6, 1929.

18 New York Times, September 6, 1929.

19 New York Sun, September 6, 1929.

20 Ibid.

21 New York Sun, September 6, 1929.

22 New York Evening Journal, September 6, 1929.