The Eastern Championship Association of 1881: An Early Minor Organization in Major League Cities

This article was written by Woody Eckard

This article was published in The National Pastime: Major Research on the Minor Leagues (2022)

The Athletic club of the Eastern Championship Association was not a direct antecedent to today’s Oakland Athletics. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

In 1881 several baseball clubs in major northeastern cities joined together to create the Eastern Championship Association (ECA). It did not claim major league status nor did it attempt to challenge the National League by locating in NL cities. The organizational model was unstable, however, with multiple club failures and mid-season entries, and one relocation. In fact, the ECA did not complete its only season, and apparently failed even to officially determine a champion. Nevertheless, it is interesting for two reasons. First, the ECA failed despite having an average city size more than twice that of the National League. Second, three ECA clubs joined the new major league American Association in 1882 and 1883.

An article by Robert Warrington in the Spring 2019 Baseball Research Journal also addresses the ECA. As he states, his article “briefly describes the formation of the Association, but focuses on the members from Philadelphia—in particular, the Phillies [emphasis added].”1 The present article instead focuses on the ECA itself. This article summarizes the brief history of the ECA, from its formation and chaotic membership to its somewhat mysterious demise, and compiles “final” standings based on game results reported in the contemporary media. Some implications can be drawn from the ECA’s experience regarding the efficient design of sports leagues.

FORMATION

The Eastern Championship Association was founded on April 11, 1881, at a meeting of several baseball clubs in New York City, with the National Club of Washington, DC, reportedly taking the lead.2 The other clubs represented were the Atlantics of Brooklyn, the New York Club, the Metropolitan Club also of New York, the Jersey City Club, and “a new Boston nine” (unspecified). Reports also mentioned that probable entrants included the Athletic Club of Philadelphia, the Albany Club of Albany, New York, and the Baltimore Club.3

As detailed in the New York Clipper, clubs could join the ECA by submitting applications by May 15, although several were admitted later.4 Any professional club—joint stock or cooperative—could enter, and there was no mention of an entry fee. Applications were to include a statement about “the club’s ability to fulfill its agreement,” without further explanation.5 The championship season was to run from April 20 to October 1, and National League playing rules were adopted. Clubs were required to play 12 games against each other during the season to qualify for the championship. Not completing this requirement meant exclusion from the championship reckoning. A judiciary committee was created to arrange the schedule of championship games and resolve other issues, but an ensuing membership tumult would dominate organization concerns and centralized scheduling likely fell by the wayside. A uniform 25 cent admission fee was specified, in contrast to the National League’s 50 cent fee.

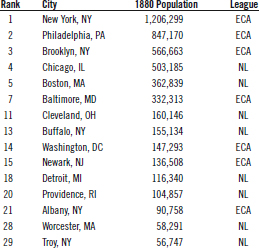

Table 1 lists ECA and National League cities ranked by population according to the 1880 US Census. No cities were shared between the two organizations.

Table 1. Top 30 1880 City Population and League Membership

The ECA claimed the three largest cities and four of the top ten: New York, Philadelphia, Brooklyn, and Baltimore. In contrast, the National League claimed only two of the top ten: Chicago and Boston. The seven ECA cities had an average population of about 475,000, well over twice the NL average of about 190,000. Even without the small cities of Worcester and Troy, the NL average was only about 234,000, still less than half of the ECA average.

MEMBERSHIP

Newspaper reports around the May 15 application “deadline” indicate that the initial ECA membership consisted of the Athletics, Atlantics, Metropolitans, New Yorks, and the Washington Club—the Nationals having changed their name.6 The Albany and Baltimore clubs joined later; the Jersey Citys did not join; and the “new Boston nine” mentioned above apparently never materialized.

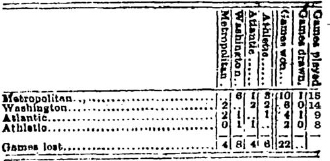

The membership picture, however, quickly became muddled. First, a June 3 report of ECA standings in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle includes only the Athletics, Atlantics, Metropolitans, and Washingtons, excluding the New York Club without explanation (See Table 2).7

Table 2. Standings of the Eastern Championship Association as Reported in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on June 3, 1881

Newspaper searches indicate that the New Yorks played no games between May 9 and June 14, an entire month. This suggests the club may have disbanded. However, on June 11 the Eagle reported standings that included the New Yorks, stating that “The New York Club has re-entered the arena.”8 A June 25 New York Clipper game report confirms this, stating that on “June 15…the reorganized team of the New York Club put in a first appearance,” losing to the Metropolitans.9 But the reorganization was apparently short-lived: after July 5 no more games could be found for the New Yorks and they are excluded from ECA standings thereafter. A July 28 newspaper report indicated that they had disbanded.

The Washington Club also disbanded. On June 18 the National Republican newspaper (Washington, DC) ran an article entitled “The Death of the National [i.e., Washington] Base-Ball Club.”10 After this date no games are reported and they no longer appear in ECA standings.

During June and July, four new clubs joined the ECA: the Albanys, the Philadelphia Club (the “Phillies”), the Quicksteps of New York City, and the Domestic Club of Newark, New Jersey. A June 5 report in The Times (Philadelphia) indicated that “To-morrow…the new Philadelphia Base Ball Club will play their first match game” against the Washingtons.11 A June 19 article also in The Times stated that “the new Philadelphia Club will join the Eastern League [sic].”12 ECA membership is corroborated by a Brooklyn Daily Eagle article of June 23 stating that the Philadelphias had just joined.13 This same article also stated that the Quicksteps were now members, and they are included as members in reported standings through July 31.

A July 28 article in the Philadelphia Inquirer summarizes ECA membership as of that date: “.the Eastern Championship League [sic ]…now has seven members, as follows: Athletics, of this city; Albany, Atlantic, Quickstep and Metropolitan Clubs.; Domestics, of Newark, N.J.; and the newly-organized Baltimore Club. The New York, Philadelphia and National [i.e., Washington] clubs…have disbanded. The Philadelphia Club is now playing in Baltimore, under the management of H.C. Myers..”14

The last sentence indicates that the Philadelphia Club had in fact relocated to Baltimore as the Baltimore Club. The Evening Star (Washington, DC) of July 13 reports that “The ‘New Baltimore Base Ball Club’ has lately been organized under the management of Mr. H.C. Myers.”15

THE ECA FADES AWAY

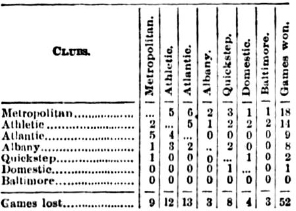

The next published standings for the Eastern Championship Association that we could find appeared in the Times (Philadelphia) on July 31, shown in Table 3.16 It includes the same seven clubs identified as members in the above-mentioned July 28 Philadelphia Inquirer article.

Table 3. Standings of the Eastern Championship Association as Reported in The Times of Philadelphia on July 31, 1881

The last published standings we found appeared three weeks later in the August 22 Brooklyn Daily Eagle.17 It included only four clubs, with the Metropolitans in first place, followed in order by the Albanys, Athletics, and Atlantics. The Baltimore, Domestic, and Quickstep clubs had apparently withdrawn and/or disbanded.

The last mention of the ECA we found was also in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, on September 1.18 It indicated that the Albany Club was disbanding, and that the remaining clubs were the Athletics, Atlantics, and Metropolitans. All three played well into October. Each met the initial ECA requirement of playing 12 games against the other two, qualifying them for the championship (see below). But no report could be found that the ECA actually declared a champion and no final standings could be located. One suspects that the complex and confusing membership changes over the summer, which confounded the championship competition, caused the media to lose interest. (In 1880, the National Association, in its fourth and final year of operation, met a similar fate. Starting its championship competition with only three clubs, a fourth joined and then two disbanded leaving but two contenders by early August. After that point, media reports disappeared.)

THE “FINAL” STANDINGS

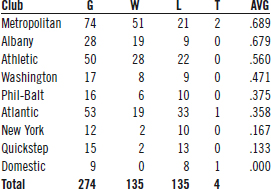

As noted above, no standings for the Eastern Championship Association could be found after August 22. Newspapers apparently had lost interest. Table 4 shows final standings based on the author’s analysis of reported game results among all nine ECA members, including those that disbanded. (Note that the Philadelphia and Baltimore clubs have been combined as a single relocated franchise.)

Table 4. Final 1881 Standings of the Eastern Championship Association as Determined by the Author

The Metropolitans led with a .708 winning average and the Albanys were close behind at .679. At the other end, the bottom three clubs had a combined 4-31-1 record with a 0.114 winning average. The variation in ECA games played was large, caused by the several mid-season failures and late entrants. The Mets played the most at 74, followed by the Atlantic and Athletic clubs at 53 and 50, respectively. In contrast, five clubs played 17 or fewer games.

As noted above, the three clubs meeting the ECA 12- league game requirement were the Metropolitans, Athletics, and Atlantics. Their records among themselves for those games were 15-8-1, 11-13-0 and 9-14-1, respectively. Thus, the Mets appear to have won the championship. The Albanys did not meet the requirement, but were 12-9-0 against this group, and 4-6-0 against the Mets.

The relative strength of the ECA and National League is of interest and can be gauged by interleague play. The Metropolitans and the Athletics played a significant number of such games, 59 and 27 respectively. The Mets won 18 of theirs for a 0.305 winning average. This is somewhat better than the League’s mean 8th place winning average of .272 during 1876 to 1891, the last year before the American Association merger.19 However, the Athletics managed to win only four of their 27 games for a .148 winning average. The three other ECA clubs with National League games had a combined 2-13-0 record and a similar .133 winning average. Thus, overall, the ECA did not approach the NL in terms of team strength.

DISCUSSION

It would seem that a league of first class clubs in the several major eastern cities not occupied by the National League could have been successful. But by any objective standard, the Eastern Championship Association was a failure. After August it was basically ignored by the media, likely because of the confusion regarding the championship competition created by membership instability. If the ECA declared an official champion at season’s end, that was not reported in the newspapers. If it officially was dissolved before the season’s end, that also was not reported. Oddly, a detailed statistical review of the Metropolitan’s season, published by the New York Clipper on November 26, made no mention of the ECA even though the Mets likely would have been the champion.20

Nevertheless, the ECA can be said to have spawned three major league teams: the Athletics, Baltimores, and Metropolitans. In 1882 the Athletic and Baltimore clubs became charter members of the new major league American Association, finishing second and sixth, respectively, among six teams.21 And after a year operating as an independent, the Metropolitans joined the American Association in 1883 and finished fourth in an expanded eight club circuit.22 (It should be noted that none of these clubs are direct antecedents of their modern namesakes.)

The failure of the ECA cannot be attributed to insufficient populations in member cities. This plagued the National Association of 1871-75, the first all-professional organization, and the professional non-major International/National Association of 1877-80. As noted above, the ECA’s average city population was over twice that of the National League.

A more likely explanation is that the ECA eschewed the National League’s tight centrally controlled organizational model. Instead it adopted a looser, more haphazard structure similar to that of the two other significant pre-1882 professional organizations. Entry was open and there were no standards regarding club financing, management, or playing grounds. Also, the ECA allowed multiple clubs in the same city. New York City had three, two of which failed by mid-August, and Philadelphia had two, one of which re-located to Baltimore in July. Also, the Atlantics and Domestics were actually within the greater New York metro area. Last, game scheduling was likely left to individual clubs given the membership turnover, although this is not clear.

The founders of the American Association that began play in 1882 no doubt were observing the decline of the Eastern Championship Association over the summer of 1881. This might have influenced their decision to adopt the National League’s more efficacious organizational model.

WOODY ECKARD is a retired economics professor living in Evergreen, Colorado, with his wife Jacky and their two dogs Petey and Violet. During his academic career he published over 50 papers in refereed academic journals, with several focused on sports economics. Five of these papers relate to Major League Baseball, including three on the nineteenth century game. He is a Rockies fan, both the ball club and the mountains, and a SABR member for over 20 years.

Notes

1. Robert D. Warrington, “Philadelphia in the 1881 Eastern Championship Association,” SABR Baseball Research Journal (Spring 2019): 78.

2. “Base-Ball: Special Dispatch to The Chicago Tribune,” Chicago Tribune, April 12,1881, 3.

3. “An Eastern Championship Ball (sic) Association,” Boston Globe, April 12,1881, 2.

4. “An Eastern Championship,” New York Clipper, April 16,1881, 58.

5. “An Eastern Championship,” New York Clipper.

6. “Base Ball Notes,” The Boston Globe, May 17,1881,1.

7. “Sports and Pastimes: Base Ball,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 3, 1881, 1.

8. “Sports and Pastimes: Base Ball,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 11, 1881, 2.

9. “Metropolitan vs. New York,” New York Clipper, June 25, 1881, 220.

10. “The Death of the National Base-Ball Club,” National Republican (Washington DC), June 18, 1881, 3.

11. “A New Base Ball Club,” Tmes (Philadelphia), June 5, 1881, 2.

12. “Base Ball Matters,” Times (Philadelphia), June 19, 1881, 2.

13. “The Local Professional Season,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 23, 1881, 1.

14. “Base Ball: Eastern League Championship,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 28, 1881, 2.

15. “Out-of-Door Sports,” Evening Star (Washington DC), July 13, 1881, 4. See also Warrington, “Philadelphia,” 82.

16. “The Base Ball Season,” Times (Philadelphia), July 31, 1881, 2.

17. “The Eastern Championship,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 22, 1881, 3.

18. “Sports and Pastimes: Base Ball,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 1, 1881, 3.

19. The years with six League members, 1877 and 1878, are excluded from the 8th place winning average calculation.

20. “The Metropolitan Club Season,” New York Clipper, November 26, 1881, 588.

21. Regarding the Athletics, see Warrington, “Philadelphia,” 83. Regarding Baltimore, the 1881 ECA club was an antecedent of the 1882 AA club. By the authors research, Henry C. Myers managed both clubs and represented the AA Club at pre-season AA meetings, and four of the top six AA club players, by games-played, were also on the ECA club. See also the March 29, 1882, Baltimore Sun on the reorganization of the Baltimore Base Ball Club.

22. Peter Mancuso, “Jim Mutrie,” SABR Biography Project, February 2022, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/jim-mutrie. Mutrie managed the Mets from 1880 to 1884.