The First and Last Games at the Polo Groundses

This article was written by Stew Thornley

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Big Apple (New York, 2017)

Examining the life span of a baseball stadium by profiling its first and last games is an interesting exercise—even more interesting when it becomes a number of different stadiums. This is the case with the Polo Groundses, four or five—depending on how one counts them—samely-named stadiums. Taking a look at ten different games over an 80-year span tells more than just the hits and errors in a particular game; it traces the history of baseball in America’s largest city.

Varying definitions of stadiums also lead to differing numbering systems among stadium aficionados (some refer to the original Polo Grounds as two stadiums since it had two diamonds). Just to add to the provocativeness of it all, other issues of contention arise.

Contention isn’t the goal of this article; it’s to be a summary of the first and last games, with accompanying information perhaps at times illuminating the issues surrounding oddly-shaped stadiums with an equally odd name for most of them, since polo was played only in the original version.

While others may differ, the author here refers to the original site as Polo Grounds I—even though there were two diamonds. Because the grounds had one diamond in the southeast corner and another in the southwest corner, some have labeled the different diamonds as Polo Grounds I and Polo Grounds II; I consider the entire facility as one stadium, labeling it as such while noting that it had two diamonds.

POLO GROUNDS I

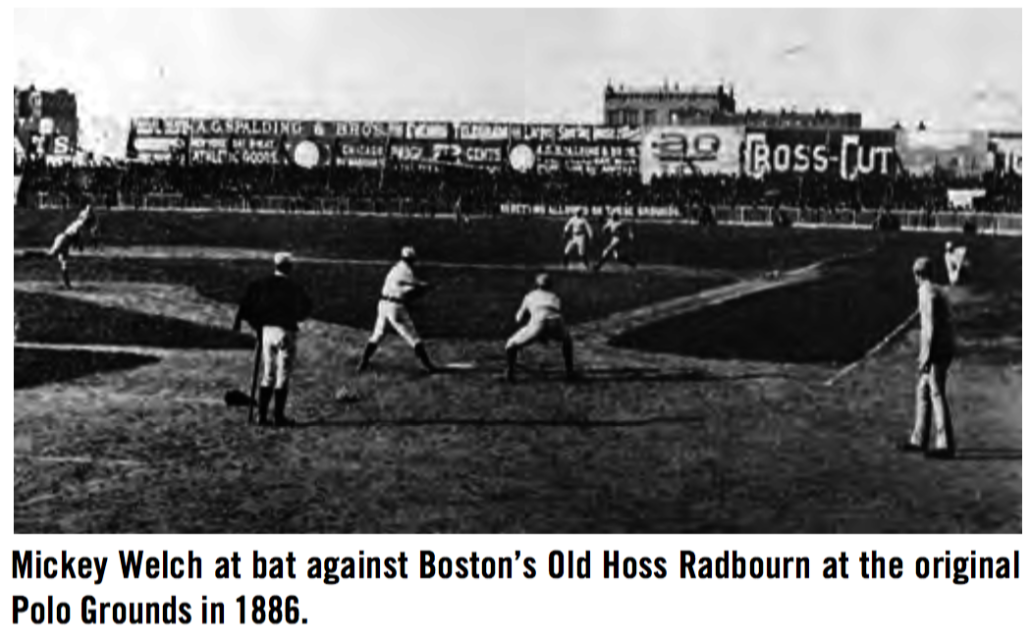

These were actual polo grounds, extending from Sixth to Fifth avenues and wedged between 110th and 112th streets just north of Central Park. Professional baseball first arrived in 1880, and major-league baseball (the focus here) came in 1883.

Since there were two diamonds, there were two first and two last games here. And the final game on the southwest diamond is, in this author’s mind, not a certainty.

What is certain is the first major-league game on each of the diamonds.

First Game—Southeast Diamond

The New York National League team played its first game on the southeast diamond—the one with the elaborate grandstand—on Tuesday, May 1, 1883. This team eventually became known as the Giants. Many sources cite Gothams as the original nickname, although the author has yet to find that usage in any of the newspapers.1

The first game for the New-Yorks—as The New York Times referred to the team—was also the first major-league game on Manhattan Island.2 A previous team representing the city in the National League played in Brooklyn, which still had nearly another 15 years as a separate city ahead of it.

The city was ready for baseball. “The residents of Harlem were awakened from their usual state of quiet and repose yesterday afternoon by seeing immense crowds of people coming up town on their way to the Polo Grounds,” reported the New York Tribune.3

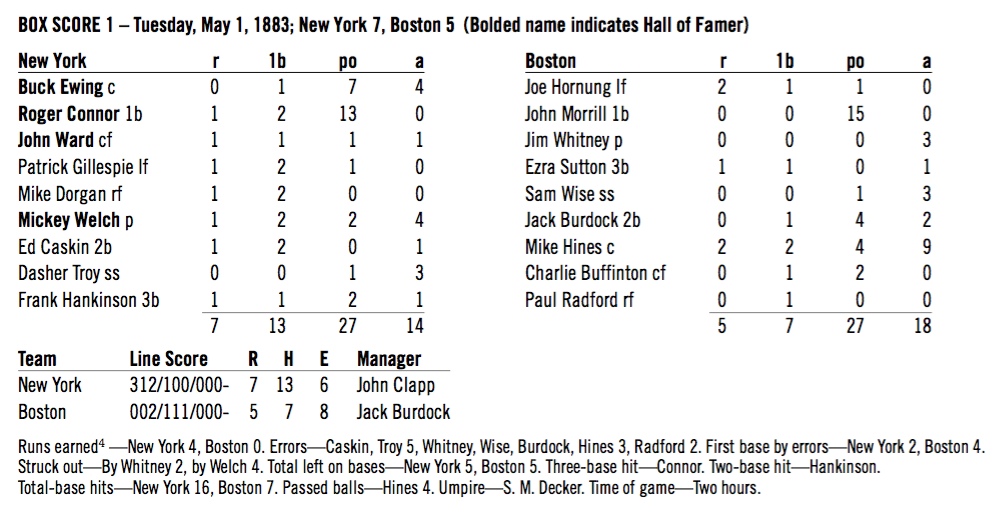

The crowd was reported at more than 15,000, one of the spectators being General (and former president) Ulysses Grant. New York batted first, built a 6–0 lead and held on for a 7–5 win over Boston. The New-Yorks had a lineup that featured four players now in the Hall of Fame—catcher Buck Ewing, first baseman Roger Connor, center fielder John Montgomery Ward, and pitcher Mickey Welch. (See Box Score 1.)4

First Game—Southwest Diamond

New York had two new major league teams in 1883. In addition to the National League Club, a team called the Metropolitan played in the American Association.5 Both the New-Yorks and the Metropolitan were owned by the Metropolitan Exhibition Company, of which John B. Day, a Tammany politician and wealthy baseball wannabe, was principal owner. Day planned to have his Association club play at the opposite end of the Polo Grounds from the New-Yorks and carved out a diamond in the southwest corner. The diamond wasn’t ready for the Metropolitan’s first home game, causing the team to use the southeast diamond.

On Decoration Day May 30, the southwest diamond was ready, and it was needed, because the New-Yorks were at home. Not only did the National League team have two games scheduled, the college national championship game was played in between.

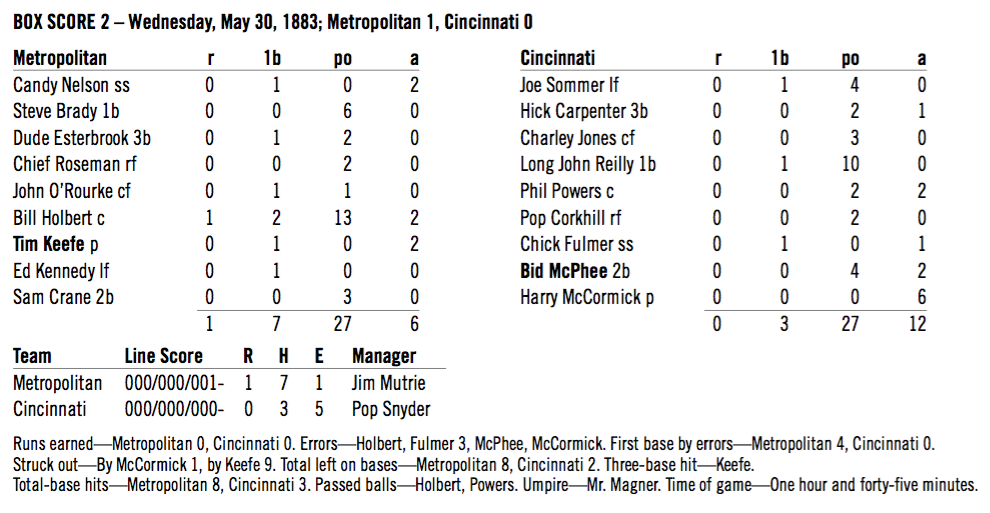

On the southwest diamond, the Metropolitan also had two games scheduled—against two different teams, Cincinnati and then Columbus.6 The game against Cincinnati, which started at 9:30A.M., was the first on the southwest diamond. Tim Keefe, another future Hall of Famer, shut out Cincinnati, 1–0, as the Metropolitan came up with a run in the top of the ninth for the win. (See Box Score 2.)

With games going on at both ends of the grounds, a flimsy, canvas-covered fence separated the playing areas. Balls rolling under the fence remained in play, causing the bizarre scene of an outfielder emerging into the opposing field in pursuit of a ball. Although outfielders proved agile and adept at getting under the fence and to the fugitive balls, occasionally a hit that rolled under the fence ended up as a home run.

Starting on Decoration Day, the League and Association teams were at home over the next couple of weeks, so the canvas fence remained up with the teams operating at opposite ends. The Metropolitan then took off on a long road trip and didn’t return until July 23.

By then, the New-Yorks were away, leaving the entire Polo Grounds open. The question is, did the Metropolitan play on the southwest or southeast diamond? Many stadium scholars express certainty that the Association team played on the southeast diamond whenever it was available and played on the west end only when there was a conflict.

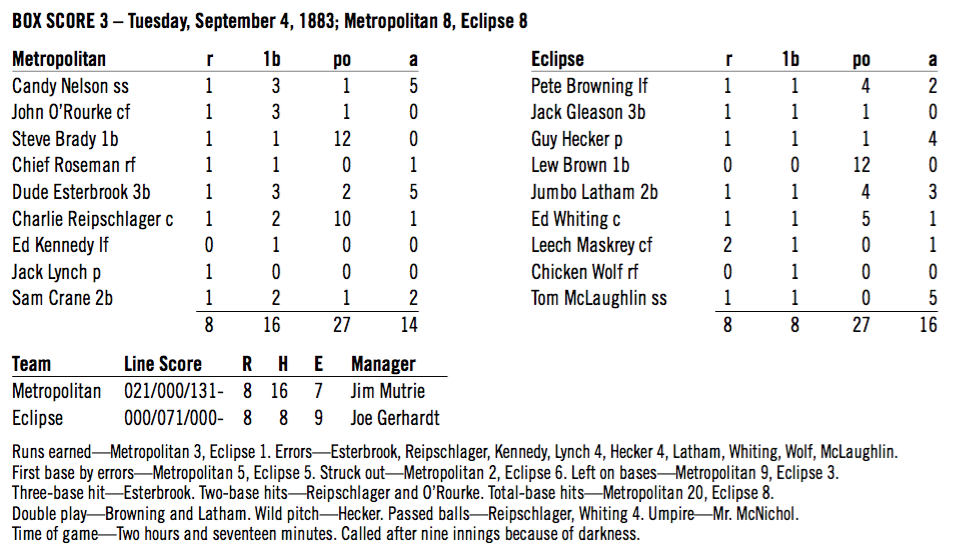

The author of this article—while acknowledging the likelihood of this—isn’t as convinced as others, whom the author believes are being swayed by nebulous evidence.7 Nevertheless, it seems more likely that the final game on the west diamond was September 4, two days before the Metropolitan’s final home game, which was probably played on the southeast diamond.

Last Game—Southwest Diamond

The opponent September 4 was the Eclipse (Louisville), which took the lead with seven runs in the fifth inning. Down by five runs after six innings, the Metropolitan caught up and tied the score in the ninth. When the Eclipse couldn’t counter in the bottom of the inning, the game was called by darkness and ended in an 8–8 tie. (See Box Score 3.)

Last Game—Southeast Diamond

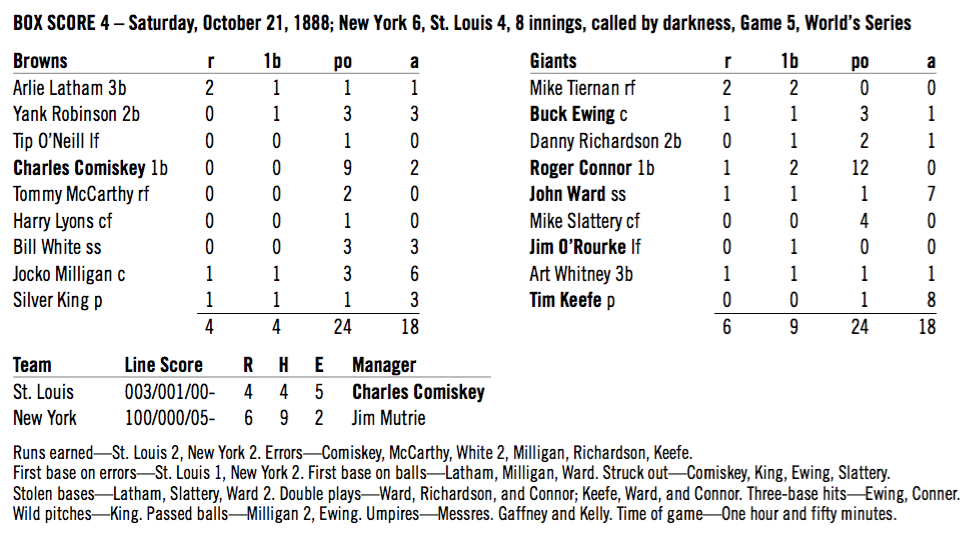

The southwest diamond disappeared from the Polo Grounds after the 1883 season; eventually, so did the Metropolitan. The National League team, soon known as the Giants, continued playing in the southeast corner and made it to the World’s Series in 1888, playing the American Association champion St. Louis Browns in a series set at 10 games.

Four of the first five games were at the Polo Grounds, and the fifth game, on October 20, was the final game on the original Polo Grounds. The Giants trailed, 4–1, going into the last of the eighth but rallied for five runs. Buck Ewing brought in a run with a triple and then scored the tying run on an infield out. Roger Connor tripled and came home with the go-ahead run on a single by John Montgomery Ward, who added insurance via a stolen base, error, and passed ball. When the inning ended, umpire John Gaffney called the game because of darkness.

The Giants went on to win the series, six games to four. Until the Atlanta Braves closed Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium with a World Series game in 1996, the Polo Grounds on 110th Street was the only stadium to finish its history with a World’s/World Series game. (See Box Score 4.)

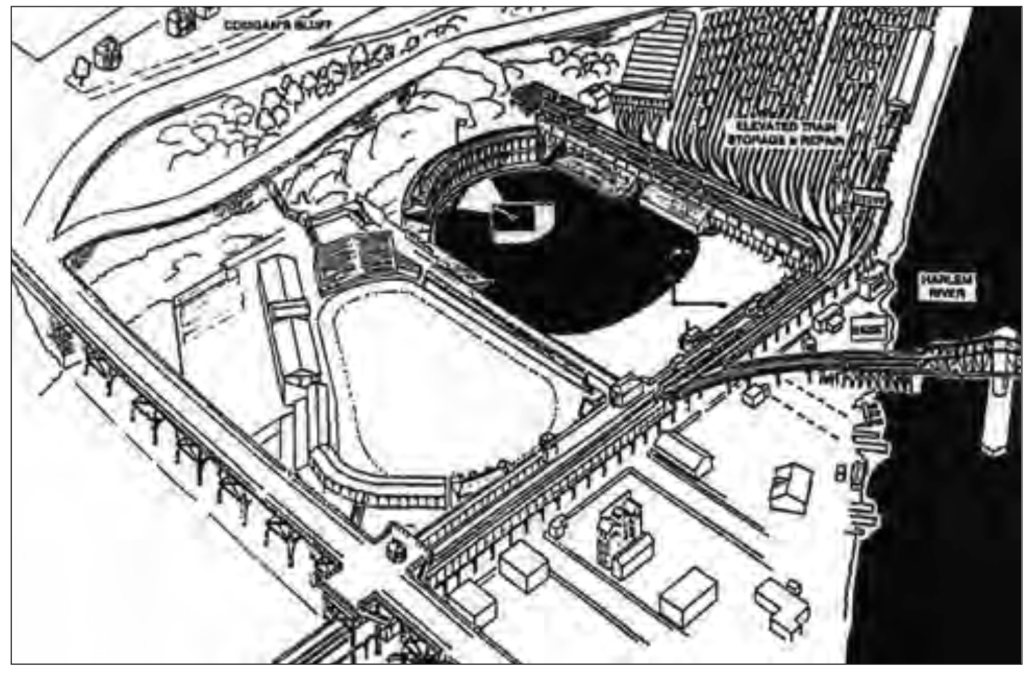

On the left is the Polo Grounds that opened in 1889. On the right is the new ballpark that opened to the north of the “New” Polo Grounds in 1890. Originally used by the New York team in the Player’s League and known as Brotherhood Park, it was taken over by the National League Giants in 1891 and renamed the Polo Grounds. The stadium the Giants abandoned took the name Manhattan Field. Its grandstand remained for several years, and the playing area was used for a variety of activities.

POLO GROUNDS II

First Game

Early in 1889 New York City moved ahead with plans to re-open 111th Street, which had been interrupted by the Polo Grounds between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, the site occupied by the Giants.

The Giants opened 1889 as an itinerant bunch, playing first in New Jersey and then on Staten Island before Day found a site just off the Harlem River in the southern half of Coogan’s Hollow in Manhattan, beneath the 155th Street viaduct and along Eighth Avenue. Day was concerned about confusion among fans as the team prepared for its third home of the season. He knew that New Yorkers associated the name Polo Grounds with his baseball team, so—to send an unambiguous message as to where the Giants would be headquartered—he christened the quarters the New Polo Grounds.8

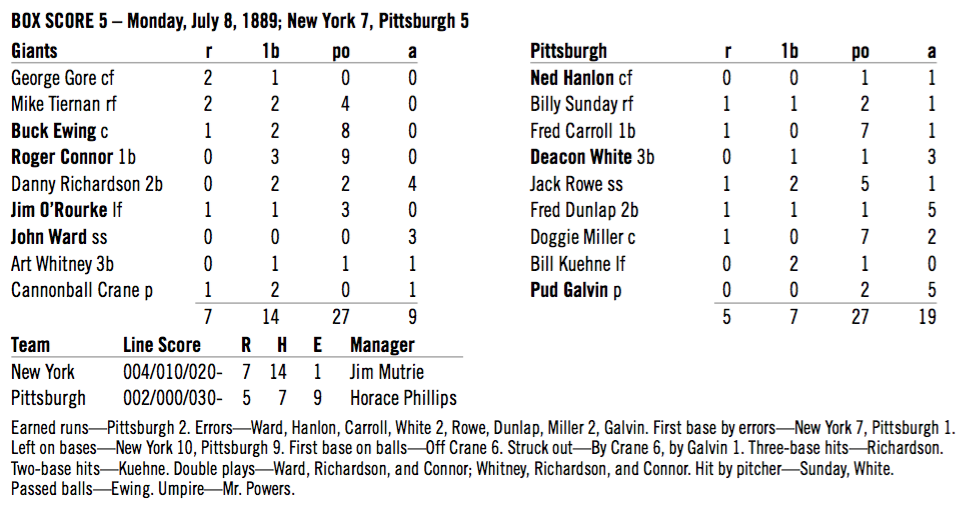

Barely two weeks after work had begun to convert a field to a stadium, the Giants opened the New Polo Grounds with a game against Pittsburgh on Monday, July 8. Newspapers reported the crowd inside the stadium as more than 10,000, even though fewer than half that many seats were available. Many of those denied access retired to a beer garden across the street, an establishment that offered at least a partial view of the game through its windows. A larger group occupied the high ground to the west of the stadium. This area—officially Coogan’s Bluff—was dubbed “Dead-Head Hill” by The New York Times, which observed that the onlookers from the hill “were bunched together as closely as chocks in a dude’s trousers.”9

Cannonball Crane outhurled Pittsburgh’s Pud Galvin—a right-hander who had already amassed more than 300 pitching wins in his career—and also started a four-run third-inning rally with a single. New York beat Pittsburgh, 7–5. (The Giants would go on to win the pennant in 1889 and beat the Brooklyn Bridegrooms of the American Association in the World’s Series.) (See Box Score 5.)

Last Game

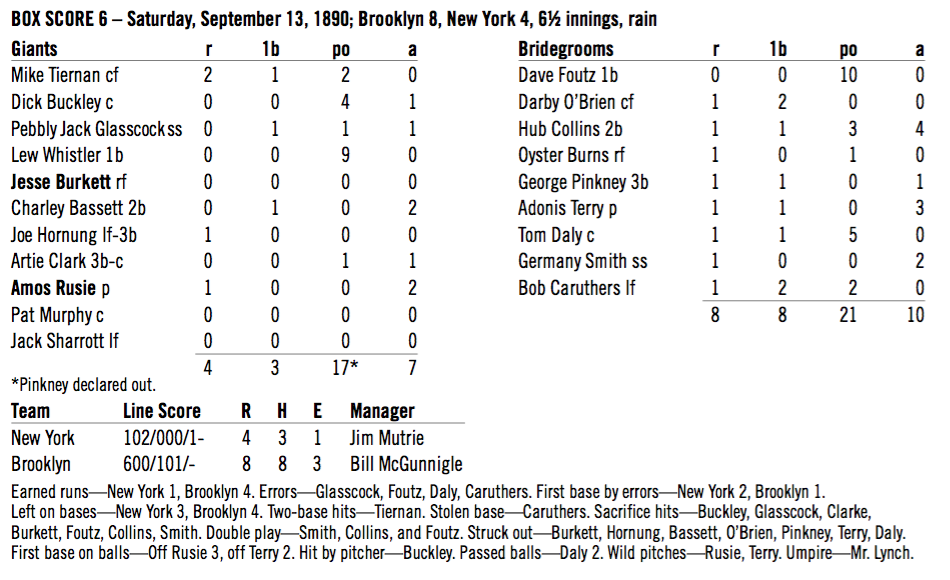

Brooklyn moved to the National League in 1890 and played the Giants more frequently. New York’s final home game of the season—on Saturday, September 13—was against Brooklyn and also the final major-league game in this edition of the Polo Grounds.

A doubleheader had been scheduled, but the teams weren’t even able to make it through all of the first game. The Giants trailed, 8–3, after six innings and scored a run in the top of the seventh before rain stopped play. The final score has been listed as 8–4 and 8–3, depending on if the Giants’ final run is counted in the uncompleted inning. (Per the rules in the Spalding Guide, the run should not have counted.) (See Box Score 6.)

This box score, counting the run scored by New York in the top of the seventh, is from The New York Times. Retrosheet lists the score in this game as 8–3 for Brooklyn, indicating that the uncompleted seventh inning was erased with the score reverting to the sixth inning.

POLO GROUNDS III

In 1890 the National League had a neighbor in New York as a new league—the Players’ National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs—formed. Backers of the New York team in what became known as the Players’ League leased the northern section of Coogan’s Hollow and built a stadium, Brotherhood Park, next to the Polo Grounds.

The Players’ League lasted only one season, and the Giants moved into the northern space, carrying the name Polo Grounds with them again.

First Game

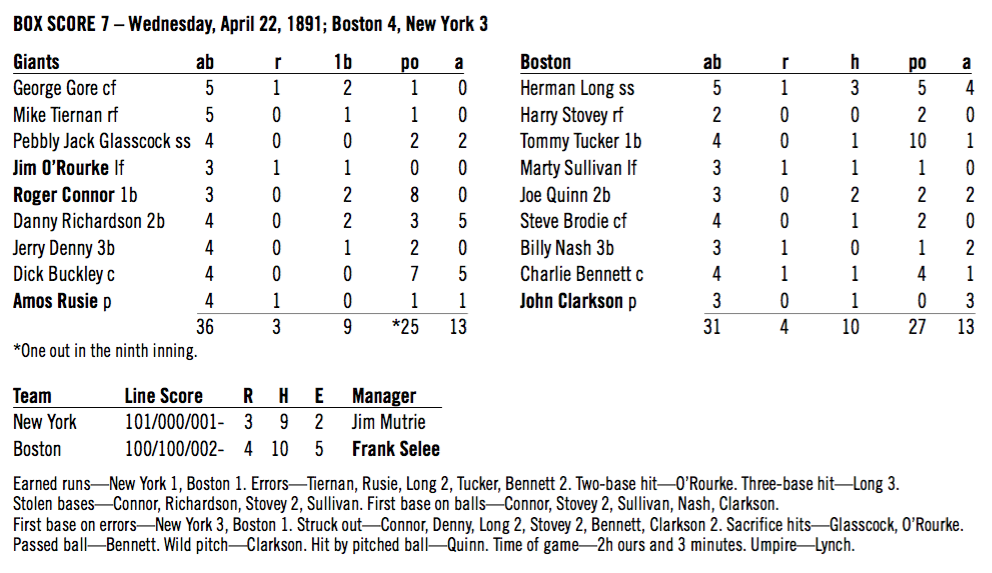

The first National League game in Polo Grounds III was played on Wednesday, April 22, 1891, and a huge crowd was on hand to see the Giants reunited. Before the game, Giants who had remained with the National League team lined up on one side of the field with those who had gone to the Players’ League on the other. The two sides then came together to indicate that past differences were settled and that they were one team again.

Amos Rusie pitched for New York, John Clarkson for Boston, and the game was tied, 2–2, after eight. Rusie came home with the go-ahead run in the top of the inning on a single by George Gore, but Gore undid the good of his hit in the bottom of the inning. Boston had two on and one out when Herman Long sent a fly to center. “Gore started after it, and to the great discomfiture of the vast throng he lost his footing and fell,” reported the Times.10

The Boston Globe provided a different perspective: “Long came up with his long bat and hit the ball hard, but it sailed high and George Gore started to get under it, having plenty of time. He misjudged, however, and then made a muff of it, high over his head, the ball rolling along the field as Gore lay in a heap on the ground, having tangled himself up in reaching for the ball.”

The newspapers also differed on whether Gore was charged with an error or Long credited with a triple (as is indicated in the accompanying box score); in either case, two runs scored to give Boston a 4–3 win. (See Box Score 7.)

Last Game

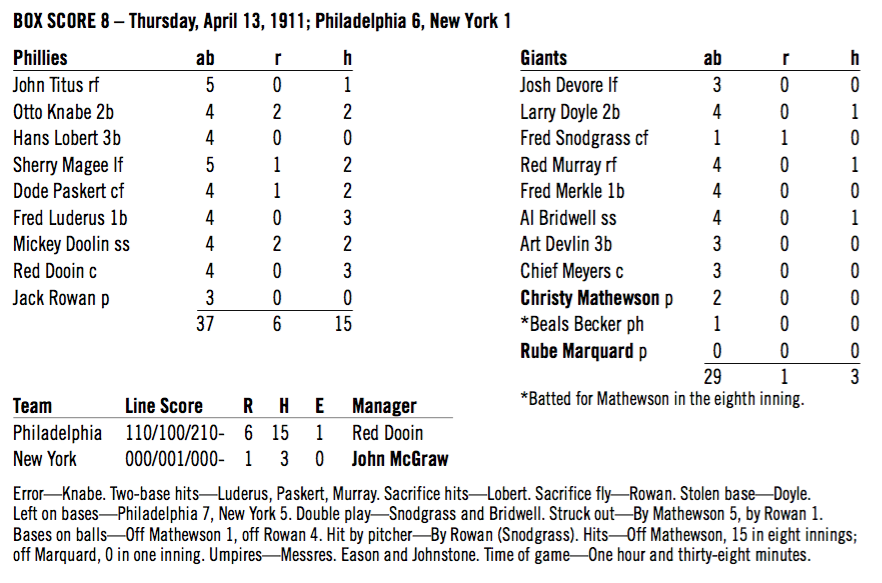

The Giants remained in the Polo Grounds for nearly 20 years and expected to use the stadium longer. They lost to the Phillies, 6–1, in the second game of the 1911 season, a Philadelphia win preserved by a great catch by center-fielder Dode Paskert.11 Early the next morning a fire began in the grandstand, spreading quickly and destroying all but some bleachers in left field and the clubhouse/office building at the Eighth Avenue end.

A young sportswriter, Fred Lieb, was taken by the late-inning catch made by Paskert and years later reflected in his memoirs on the event and the fire that followed hours later. He wrote, “Reporters who were there liked to call the official account of the fire’s origin nonsense: it was Paskert’s electrifying and sizzling catch, they said, that sparked the Polo Grounds holocaust.”12 (See Box Score 8.)

POLO GROUNDS IV

The Giants accepted an offer from the nearby New York Highlanders/Yankees to move into American League Park as they figured out what to do about a new stadium. Owner John Brush decided to rebuild on the same spot but with more durable materials.

In fewer than three months, a burgeoning steel-and-concrete stadium with 16,000 seats was ready.

First Game

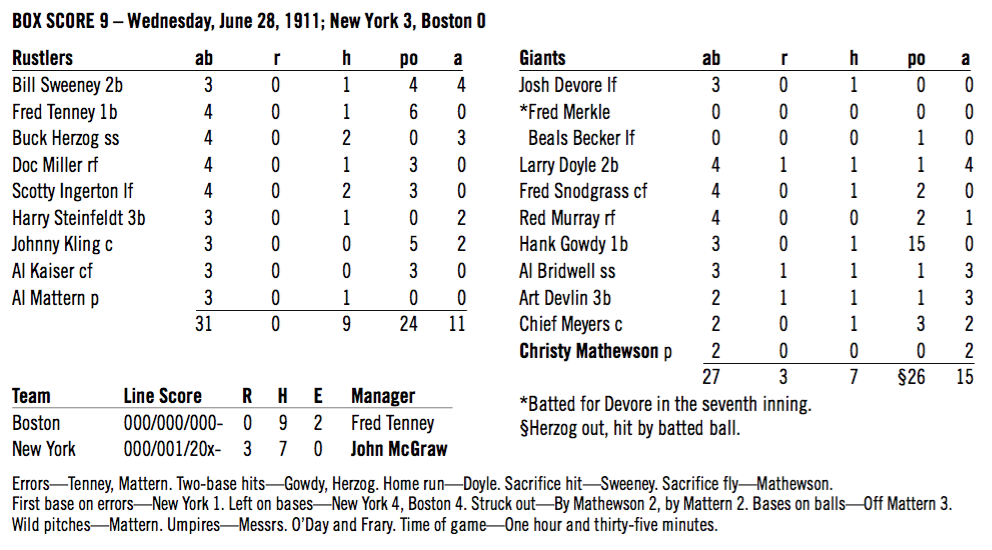

Christy Mathewson was on the mound against Boston—then at least informally known as the Rustlers—on Wednesday, June 28, 1911, for the first game of the final Polo Grounds.

Laughing Larry Doyle broke a scoreless tie in the bottom of the sixth with a home run into the right-field grandstand. It was all Matty needed, but his mates gave him two more runs as New York beat Boston, 3–0. (See Box Score 9.)

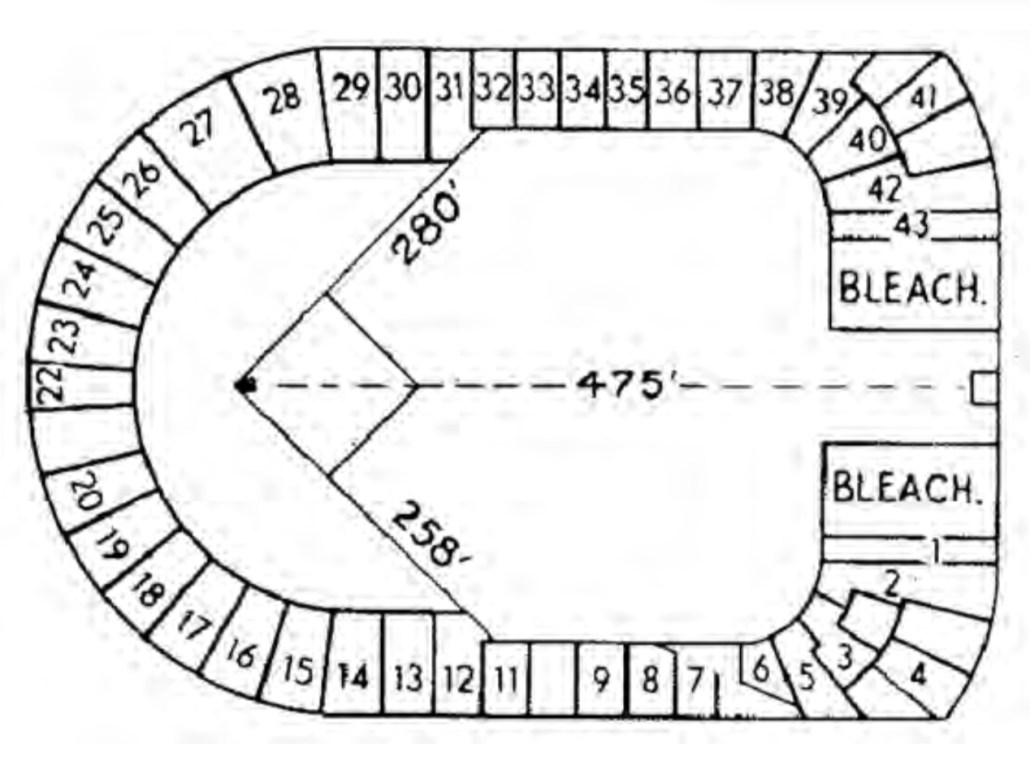

Through the decades the Polo Grounds expanded, keeping the familiar horseshoe shape of the predecessor, with the ridiculously short distances down the foul lines and even more absurd distance to center field. A gap between the bleachers was filled by the clubhouses and offices, set back to form a notch that contained monuments and stairways—all in play.

For much of the history of Polo Grounds IV, a 483-foot marker was attached to the clubhouse wall in center field. When the Mets moved into the Polo Grounds, the distance was listed as 475 feet.

Last Game

The Polo Grounds had several last games—at least what were thought to be the finales for the stadium.

The end of the New York Giants came with a 9–1 loss September 29, 1957. The Giants were off for the West Coast, but the Polo Grounds survived—used for other events—to still be around when another New York team in the National League, the Mets, began in 1962. A new ballpark in Queens was being built and was to be ready the following year as the Mets used the Polo Grounds in the interim.

On September 23, 1962, a crowd of 10,304 came out for another last game as the Mets beat the Cubs, 2–1.13

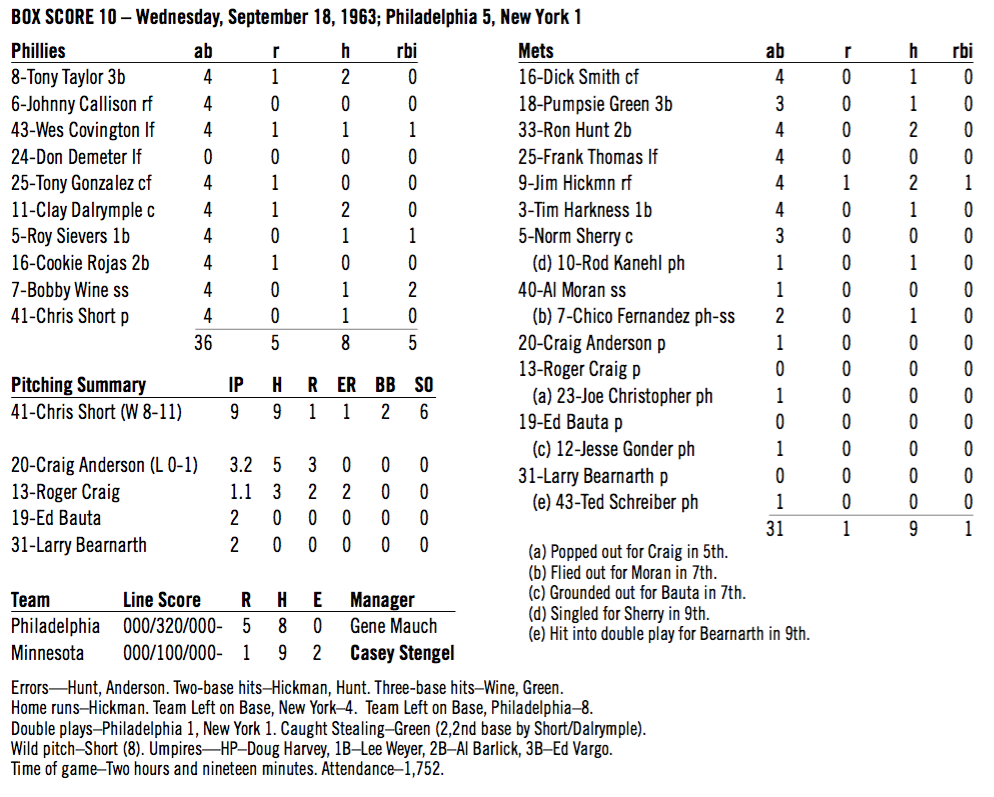

However, the new stadium still wasn’t ready, so the Mets had one more year in the Polo Grounds. Fewer than 2,000 fans were on hand for what really was the final game, a 5–1 loss to the Phillies on Wednesday, September 18, 1963.

“Maybe the fact that there had been two previous ‘last games’ at the Polo Grounds took a bit from the occasion,” wrote Gordon S. White, Jr. in The New York Times. “It is hoped that no more Mets games will be played at the Polo Grounds—if only to put an end to the string of finales.”14

Jim Hickman gave the Mets their only run with the final home run ever hit in the Polo Grounds. (See Box Score 10.)

Baseball was still played there, one more time, in October in a Latin All-Star Game, the National League beating the American League, 5–2.15 The New York Jets played out their football season, and the final event—a 19–10 loss to the Buffalo Bills—finished the Polo Grounds December 14, 1963.

History—from Merkle’s Boner to Mays’s Catch—all took place at some version of the Polo Grounds.

STEW THORNLEY is the author of “Land of the Giants: New York’s Polo Grounds” and editor of a soon-to-be-published anthology of the Polo Grounds. He received the USA Today Baseball Weekly Award for best research presentation at the 1998 SABR convention in San Francisco for a presentation on the Polo Grounds. Stew has been a SABR member since 1979.

NOTES

1 Nicknames were nebulous in the nineteenth century and beyond. Although reliable reference sources list nicknames for teams, some are “blatantly bogus,” according to SABR member and nineteenth-century expert Richard Hershberger.

2 The Times dropped the hyphen in New-York on December 1, 1896.

3 “Baseball News,” New-York Tribune, Wednesday, May 2, 1883, page 2. The Tribune dropped the hyphen in New-York on April 16, 1914.

4 Note that here and elsewhere, “runs earned” are those earned by batting, not in the modern sense of “earned runs.” Box scores replicate what appeared in the newspapers of the time.

5 The American Association had more of a focus on names than cities, differing from the National League. The Eclipse (representing Louisville), Alleghenys (representing Pittsburgh), and Athletics (representing Philadelphia) are among the examples of teams that shared the convention of the team representing New York, the Metropolitan.

6 Cincinnati and Columbus were also playing two games against different opponents, criss-crossing with one another by playing in Philadelphia as well as New York.

7 It’s clear that the southwest diamond was not constructed to be used only when there was a conflict with the east diamond. However, it’s possible that after seeing how inferior the playing and seating areas were in the southwest corner that John B. Day decided to have the Metropolitan play on the southeast diamond whenever possible. The nebulous evidence is that New York newspapers had ads for all home games, and the ads directed patrons to the Fifth Avenue or Sixth Avenue entrance, an indication of which diamond would be used. This is partially true; the specifics on the entrance, however, appeared only when both teams were at home. It’s known which diamond was used by which team in these situations. The entrance information does not appear in the ads when only one team was at home—information that could confirm if the Metropolitan used the southeast diamond whenever it was available or if it used the southwest diamond, as was the plan before the season.

8 “A New Baseball Field: The Giants Will Play Games in This City Again: Grounds Secured on the West Side of Town in a Convenient Place,” The New York Times, Saturday, June 22, 1889, 2; “The Giants New Grounds: A Home for Them on Manhattan Island at Last,” New-York Tribune, June 22, 1889, 7.

9 “The Giants Are at Home: They Open Their New Grounds in Grand Style,” New-York Times, Tuesday, July 9, 1889, p. 3; “A Royal Christening: Happy Giants Welcomed to Their New Grounds,” New-York Tribune, July 9, 1889, 2.

10 “Boston Defeats New-York: Over 17,000 Persons Witness the Opening League Game: The Giants Looked Like Winners to the Ninth Inning, but Lost by an Accident,” New-York Times, Thursday, April 23, 1891, page 2; “Grand Send Off: League Teams Begin the Battle for the Pennant: Over 17,000 People See the Game in Gotham: Boston Plays in Luck and Wins in the Ninth,” Boston Globe, Thursday, April 23, 1891, 11.

11 Paskert’s Catch: “Phillies Flay ‘Big Six’s’ Pitching,” The New York Times, Friday, April 14, 1911, p. 2.

12 Fred Lieb, Baseball As I Have Known It (New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan,Inc., 1977), p. 35; “Polo Grounds Swept by Fire,” The New York Times, Friday, April 14, 1911, 1.

13 “Mets Beat Cubs, 2-1, in Farewell to Baseball at the Polo Grounds” by Robert M. Lipsyte, The New York Times, Monday, September 24, 1962, 24.

14 “Era of Mets Ends at Polo Grounds” by Gordon S. White Jr., The New York Times, Thursday, September 19, 1963, 32.

15 “National Leagues Triumph at Polo Grounds, 5-2: Latin All-Stars Paced by M’Bean” by William J. Briordy, The New York Times, Sunday, October 13, 1963.