The Negro Leagues Beyond 1948, and The Adventures of a Boy Named Willie

This article was written by Alan Cohen

This article was published in Willie Mays: Five Tools (2023)

By consensus, it has been deemed that the Negro Leagues died in 1948. The last Negro League World Series was played that year. SABR’s book on the 1948 Homestead Grays and Birmingham Black Barons was titled A Bittersweet Goodbye. Seamheads, an authority on Negro Leagues history, does not go beyond 1948. When Retrosheet began doing individual game records, it began with 1948 and went backward.

By consensus, it has been deemed that the Negro Leagues died in 1948. The last Negro League World Series was played that year. SABR’s book on the 1948 Homestead Grays and Birmingham Black Barons was titled A Bittersweet Goodbye. Seamheads, an authority on Negro Leagues history, does not go beyond 1948. When Retrosheet began doing individual game records, it began with 1948 and went backward.

As we begin to look at the statistics of Black ballplayers who broke into the American and National Leagues and view their records on Baseball-Reference.com, there is a gap. With Willie Mays, we know his record with Birmingham in 1948, and we know his record with Trenton in 1950. What happened in between?

In these paragraphs, the story begins to unfold of the Negro Leagues beyond 1948 and some of Mays’ early glories.

After 1948, two teams (the Homestead Grays and New York Black Yankees) left the Negro National League. To survive, the four remaining NNL teams combined with the six Negro American League teams to form a new league. The new 10-team league, called the Negro American League, had a limited schedule, with most games played on weekends. On August 14, 1949, the East-West All-Star Game was once again held at Comiskey Park and drew a good-sized crowd (31,097) to see the top players in the league. One player from that game, Jim Gilliam of the Baltimore Elite Giants, went on to have a great career with the Dodgers in Brooklyn and Los Angeles.

One Negro League player not in the game was Willie Mays of the Birmingham Black Barons. Why didn’t he play? There have been reasons given but nothing conclusive. One explanation was that he was back in high school. Another was that his mentor and manager, Piper Davis, and Birmingham team owner Tom Hayes were hiding him, fearful that teams in the White major leagues would steal him away, offering little or nothing in the way of compensation.1

But the real reason seems to be that, at the time the team was chosen in early July, Mays was in a slump and the outfielders chosen were having better years. Houston’s Johnny Davis was a top home run hitter in the league; Willard Brown of the Monarchs led the league in RBIs; Pedro Formental of Memphis led the league in triples; and Art Pennington of Chicago, who was replaced (after being sold to Portland of the Pacific Coast League) by teammate Lloyd Davenport, was among the league leaders in batting average.

How did Mays do in 1949?

The record is not yet complete; it looks as if he put his greatness on display almost from the start. Through June 5, he was batting .413.2 The Birmingham News, a mainstream daily paper, gave ample coverage to the Black Barons and included many box scores. On a rainy Sunday, May 8, the Black Barons hosted the Chicago American Giants in a doubleheader at Rickwood Field. Mays had three total hits and sparkled in the abbreviated second game, ended by curfew after five innings. His fourth-inning single broke a 1-1 tie as the Black Barons won, 4-1. He also showed off his arm, gunning down Jesse Douglas at home plate after grabbing a fly ball hit by Lonnie Summers.3

On May 10, Mays hit his first homer of the season as Birmingham lost to the Louisville Buckeyes (formerly the Cleveland Buckeyes), 7-5.4 The first game for which there is an available box score was played the next night; Mays doubled in a 4-3 win over the Chicago American Giants.5 On May 13 Birmingham completed its homestand with a 5-3 win over the Kansas City Monarchs (featuring Curt Roberts, Gene Baker, and Elston Howard). Mays singled and scored.

Mays did not accompany his team on its first road trip. His high school would not allow it. When the Barons returned home for a doubleheader on May 22, he was in the lineup for each game. Birmingham won by scores of 14-2 and 18-8 against Louisville, and Mays went 3-for-7 in the two games. His hits included a double in the opener. One of the pitchers he victimized was future San Francisco Giants teammate Sam Jones. Mays had four RBIs and a stolen base in the 14-2 game. He had a stolen base in the nightcap.6

On May 25 Mays, who walked in a run and singled and scored in another plate appearance, got raves for his glovework. Running at full throttle, he made a barehanded catch of a ball by the outfield wall in the 6-3 win over Louisville.7

Two days later, his school year complete, Mays joined the Barons as they traveled to Louisville8 before visiting New York. Birmingham faced the New York Cubans in a doubleheader at the Polo Grounds on May 29.

The New York Sunday News ran an article in late May 1949 reading: “The New York Cubans’ ‘$100,000 Infield’ will be scouted by aides of Carl Hubbell (of the New York Giants) when the Cubans oppose the Birmingham Black Barons in a twin bill which will open the local Negro American League season at the Polo Grounds today. Each of the infielders hit over .300 last season and led the league in fielding and in double plays.”9

That small article, buried in the sports section of the top circulation newspaper in the country’s largest city, gave notice that some extra sets of eyes would be in a position to take notice of Willie Mays’ first visit to the spacious center field that would be his home playground early in his career with the New York Giants.

The New York Age, a weekly Black newspaper, gave the games good coverage. Each game resulted in an 8-4 score. Birmingham won the opener, and the Cubans won the second game. In the ninth inning of the second game, Willie Howard Mays Jr. hit his first Polo Grounds home run. It was an inside-the-park homer, but there was no report as to whether his cap came flying off as he rounded the bases. Earlier in the game, he had singled in a run.10

After a game in West Haven, Connecticut on May 30, Mays made his first Brooklyn appearance on June 1, but it was not at Ebbets Field. It was at Dexter Park (located in nearby Woodhaven in Queens) against the Bushwicks, a popular semipro team that featured some veterans of the National and American Leagues. The Black Barons won, 7-4,11 hopped back on the bus and headed, after a game with the Springfield (Queens, New York) Grays on June 2 toward Baltimore to face the Elite Giants in Baltimore on June 3, Wilmington, Delaware, on June 4, and back in Baltimore on June 5 for a doubleheader. Then it was on to Philadelphia’s Shibe Park to face the Philadelphia Stars on June 6.

The bus seemed to be always in motion. There were stops at Chester, Pennsylvania (June 7), Petersburg, Virginia (June 8), and Asheville, North Carolina (June 9-10), and finally, on June 11 and 12, the Black Barons were back in Birmingham to face the Cubans. No sooner had they gotten home than they and the Cubans were back on the bus. The teams played a doubleheader at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis on June 13 and were back in Birmingham two days later, after a scheduled game in Memphis on June 14 was rained out. On June 16, it was on to Tuscaloosa. Such was life in the Negro Leagues.12

Mays’ next known home run came on June 19 at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field in the first game of a doubleheader against the Indianapolis Clowns. He went 2-for-5 and, in addition to the homer, knocked a double in a 12-5 first-game win. In the second game, a 10-8 loss, he was 1-for-4 with an RBI and a stolen base.13

A long road trip in late June took the Black Barons to Kansas City and a game against the Monarchs. The teams took the show on the road for three stops in Nebraska.

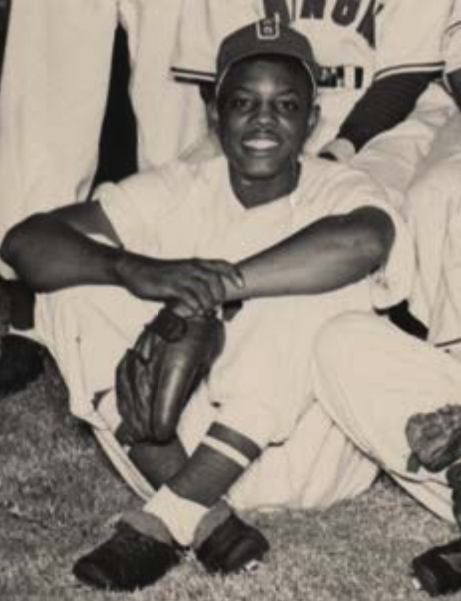

A teenage Willie Mays with the Birmingham Black Barons. Mays’ father did not allow him to join the Black Barons full-time in 1948 until school was over at the end of May. (Courtesy of Memphis Public Library)

Back at Rickwood on July 10, Mays had one of his best games with the Black Barons. He had five hits, including a double and the game-winning RBI, as Birmingham defeated the Philadelphia Stars, 13-12.14 On July 27 he put on another show for the home folks with four hits, including a triple. His fourth hit, a game-winning RBI single in the bottom of the ninth, broke a 5-5 tie.15

On August 5 against Baltimore at Rickwood Field, he had one of his better innings. In the top of the third inning, he threw out a runner at home plate and in the bottom of the same inning, he walked, stole second base and scored the tying run on a single by Ed Steele. Unfortunately for his team, Baltimore scored in the following inning and won the game, 3-2.16

On August 24 at Montgomery, Alabama, the quintessential five-tool player showed off his arm in spectacular fashion. The game was a marathon affair that lasted 15 innings. In the seventh inning, Mays snuffed out a Kansas City rally by throwing from the 387-foot sign in left-center to third base and nailing an advancing runner. Birmingham won the contest, 3-2.17 Mays hit his final home run of the season on September 23 as the Black Barons defeated the Buckeyes 7-1 at Rickwood Field. He also doubled in the game.18

By the time he hit that final homer of the 1949 season, Mays had gotten attention with a feature article in a predominant Black publication. On August 27, Russ Cowans acquainted his Chicago Defender readers with Mays, who was “coming up like a prairie fire.”19

Another type of fire broke out on Saturday, June 10, 1950. Mays had graduated from high school on May 25 and was traveling with the Black Barons to New York. As it was about to enter the Holland Tunnel, the team’s bus caught fire. The players escaped unharmed, but their equipment was consumed by the flames.20 The team played a doubleheader at the Polo Grounds the next day.

Willie Mays remained with Birmingham until he was acquired by the Giants organization on June 21, 1950.21 In his last game with Birmingham, on June 17, he doubled during a 7-1 win over the New York Cubans.22 Reports of games were not as thorough in 1950 as they had been the prior year but during his last 20 games with Birmingham, from May 24 through June 17, Mays had four doubles and four home runs. Per an article in the Chicago Defender, his 22 RBIs placed him second in the league.23

After less than a year in the minor leagues, Mays joined the Giants in May 1951 and, on May 28, 1951, on the eve of the second anniversary of his first homer at the Polo Grounds, he hit the first of his 660 National League homers.

ALAN COHEN chairs the BioProject fact-checking committee, serves as vice president-treasurer of the Connecticut Smoky Joe Wood Chapter, and is a datacaster (milb first-pitch stringer) for the Hartford Yard Goats of the Double-A Eastern League. His biographies, game stories and essays have appeared in more than 65 SABR publications. The subject of his earliest Baseball Research Journal article was the Hearst Sandlot Classic, at which Willie Mays participated in a home-run-hitting contest in 1957. His story of Mays’ return to the Polo Grounds in 1962 with the Giants was first published as part of the SABR website’s First Games Back project. He is currently involved with the Retrosheet project on Negro League Games, including Mays’ games with Birmingham from 1948 through 1950. He has four children, nine grandchildren, and one great-grandchild and resides in Connecticut with wife Frances, their cats Ava and Zoe, and their dog, Buddy.

SOURCES

Of the many biographies of Willie Mays, the following is particularly helpful in showing the development of Willie Mays with the Birmingham Black Barons from 1948 through 1950.

Klima, John. Willie’s Boys: The 1948 Birmingham Black Barons, the Last Negro League World Series, and the Making of a Baseball Legend (Hoboken, New Jersey: John A. Wiley and Sons, 2009).

NOTES

1 John Klima, Willie’s Boys: The 1948 Birmingham Black Barons, the Last Negro League World Series, and the Making of a Baseball Legend (Hoboken, New Jersey: John A. Wiley and Sons, 2009), 215.

2 “Carl [sic] Mays Regains NAL Batting Lead with .413,” Chicago Defender, June 18, 1949: 16.

3 “Black Barons Lose [sic], 6-2, 4-1,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 14, 1949: 24; “Black Barons Cop Twin Bill,” Birmingham News, May 9, 1949: 18.

4 “Buckeyes Break 5-Game Loss Streak,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 12, 1949: 11.

5 “Black Barons Edge Chicago, 4-3” Birmingham News, May 12, 1949: 48.

6 “Black Barons Win Two, Play Wednesday,” Birmingham News, May 23, 1949: 14.

7 “Black Barons Win Benefit Tussle, 6 to 3,” Birmingham News, May 26, 1949: 49.

8 “Barons Blank Buckeyes 7-0,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 28, 1949: Sports, 5.

9 “Spies to Eye Cubans,” New York Sunday News, May 29, 1949: 33C.

10 “League-Leading Cubans Split 2 as Scantlebury Strikes Out 10,” New York Age, June 4, 1949: 33.

11 “Bushwicks Drop Arc Light Opener,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 2, 1949: 21.

12 The itinerary for this road trip appeared in “Birmingham Black Barons to Play Normal Red Sox Here June 16,” Alabama Citizen (Tuscaloosa, Alabama), June 4, 1949: 7.

13 “Black Barons Split Pair with Clowns,” Birmingham News, June 21. 1949: 21.

14 “Mays’ Single Gives Black Barons Win,” Birmingham News, July 11, 1949: 18.

15 “Black Barons Nip Memphis Red Sox,” Birmingham News, July 28, 1949: 42.

16 “Baltimore in 3 to 2 Victory Over Barons,” Atlanta Daily World, August 9, 1949: 5.

17 Charles Littlejohn, “Black Barons Nip Kansas City, 3-2,” Montgomery Advertiser, August 25, 1949: 16.

18 “Black Barons Defeat Buckeyes Easily, 7-1,” Birmingham News, September 24, 1949: 9.

19 Russ J. Cowans, “Move Over, You Vets, Willie Mays is Coming Up Like a Prairie Fire,” Chicago Defender, August 27, 1949: 14.

20 “Black Barons Lose Bus, Equipment but Win Two of Three,” Birmingham News, June 13, 1950: 26.

21 “Giants Sign Black Barons’ Willie Mays,” Birmingham Post-Herald, June 22, 1950: 20; “Mays, Black Barons Star, Is Going Up,” Birmingham News, June 22, 1950: 18.

22 “Mays Bats in Four/Black Barons Win, 7-1,” Birmingham News, June 18, 1950: 44.

23 “Willie Mays Sparks Barons on Big Spree,” Chicago Defender, June 24, 1950: 17.