The Short but Exciting Life of the Havana Sugar Kings

This article was written by John Harris - John J. Burbridge Jr.

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Sunshine State (Miami, 2016)

The Havana Sugar Kings played in the International League between 1954 and 1960. It was a short existence, but a memorable one. The Sugar Kings began with hopes of a major league franchise, experienced a shooting during a home game and a political revolution, won the International League’s Governor’s Cup and the Junior World Series, and ended their stay in Havana with a one-way trip to Jersey City.

Origins of Cuban Baseball

Baseball is Cuba’s national pastime. Many would attribute its origins as such to a game played on Sunday, December 27, 1874, between Matanzas and the visiting Habana Baseball Club at Palma del Junco in Matanzas with the Habana team winning 51–9.1 The Matanzas team was composed of the crew from an American ship forced to dock in the Matanzas harbor. However, if this was the first game, how did the Habana Baseball Club originate?

While attending college at Spring Hill University in Mobile, Alabama, Nemesio Guilló, his brother Ernesto, and Enrique Porto were introduced to baseball. They returned to Cuba in 1864 desiring to bring the game to Cuba and started the Habana Baseball Club in 1868.2

The Golden Age

The period between the Spanish American War and the early 1930s has been called the Golden Age for both Cuba and Cuban baseball.3 As Cuba advanced both culturally and economically, baseball flourished at four different levels. First there was the professional game with the winter Cuban League dominating the scene. The second level was semipro baseball with teams sponsored by companies and open to all including Negro players. The third was probably the most intriguing, sugarmill baseball. Obviously, this was tied to the sugar industry with teams representing the various mills throughout the island. Finally, there was amateur baseball played by clubs many of which were in Havana. These were the descendants of the Habana Baseball Club.

Several notable Cuban players did join major league teams during this era. The most significant of these players was Adolfo Luque who pitched for the Cincinnati Reds from 1918 until 1929, and other teams in a career that spanned 1914–35. Luque’s record would include 194 major league wins.4

Another player of note was Mike Gonzalez who played for several major league teams between 1912 and 1932 and became a coach with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1934. Gonzalez was named manager of the Cardinals in 1938 when Frankie Frisch was fired. Gonzalez thus became the first Cuban manager in the major leagues.5

The Havana Cubans

While American players, mainly from the Negro Leagues, played in Cuba, it wasn’t until 1946 that a Cuban team had a presence in what Americans would call Organized Baseball. From 1946 until 1953 the Havana Cubans were in the Florida International League. Joe Cambria, a popular figure in Cuban baseball and a Washington Nationals scout who had signed Cuban players for the major leagues, organized this team and was able to affiliate them with the Washington Nationals. From 1946 to 1950, the Cubans were very successful, finishing first in the standings in each of the years and winning the league championship twice.6 However, from 1951 until 1953, the Cubans struggled on the field and change was forthcoming.

Roberto (Bobby) Maduro

On May 4, 1953, Bobby Maduro became the majority owner of the Cubans. Maduro had high aspirations. During the 1950s major league baseball franchises were relocating as evident by the Boston Braves moving to Milwaukee, the St. Louis Browns to Baltimore, and the Dodgers and Giants going to the West Coast. Bobby Maduro envisioned the possibility of a major league franchise in Havana.

In moving forward with such aspirations, Maduro obtained the rights for the Springfield, Massachusetts, franchise in the IL and got approval to move them to Havana at the end of the 1953 season. The new name of the team was the Havana Sugar Kings. With an IL franchise, Havana now had a team one level below the major leagues. Maduro was the owner of the Sugar Kings during their entire stay in Havana.

Bobby Maduro. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

The Havana Sugar Kings

With the change in ownership, the association with the Washington Nationals. also ended. The Sugar Kings became affiliated with the Cincinnati Redlegs which was appropriate given that the most prominent Cuban player in the major leagues, Luque, played with them. Maduro’s dream was to have the Sugar Kings become the epicenter of Latino baseball with players from throughout Latin America.7 In 1954 approximately 50% of the Sugar Kings roster was composed of Latino players with the remainder being Americans such as Clint Hartung and Johnny Lipon.8

The Sugar Kings, managed by Reggie Otero, finished fifth in that inaugural year but finished third in 1955 and made the playoffs. Unfortunately, the team lost to second-place Toronto in the first round. 1956 through 1958 were disappointing as the team finished in sixth, sixth, and eighth place in those respective years. In 1956 Otero was replaced as manager by Napoleon (Nap) Reyes.

The team also struggled at the gate. In 1954, 295,453 fans attended their home games, averaging approximately 4,000 per game. Given their successful playoff run in 1955, the total attendance increased to 313,232. Attendance declined from 1956 to 1958, with 1957 being the low point with an average attendance of slightly more than 1,000.9

Possibly, Cuban baseball fans were not used to baseball during the summer given that the traditional Cuban League games were in the winter. In addition, the caliber of play may have been below what the Cuban fans were used to. While the players were high-level minor leaguers, the Cuban League playing during the winter months attracted major league players. Finally, although the Sugar Kings attracted many Latino players, the Cincinnati farm team was still subject to decision-making concerning player personnel at the major league level.

Revolution

After seven years of insurrection, the Batista government collapsed on January 1, 1959. Fidel Castro, a key leader of the insurgents, quickly became Prime Minister on February 16, 1959.10 Despite continued American investment and some optimism for an economic relationship between the two countries, distrust and political maneuverings pushed the two governments apart.11 The Havana Sugar Kings were now at the nexus between two governments. They quickly became the anointed team of a new Cuban nationalism fronted by a leader who loved the sport.

Bobby Maduro met with Castro in April 1959 and was guaranteed the team a permanent home in Havana and given permission for plans for an eventual major league franchise.12 The Castro government also organized an injection of up to $70,000 to the franchise to bolster its sagging revenues.13 Some of that money came from the Cuban Sugar Stabilization Institute.14

Improving Team

While Cuba was in the midst of political turmoil, the 1959 Sugar Kings were showing the results of a rebuilding process on the field. Younger Cuban players were replacing older favorites and Preston Gómez had been hired to manage. Of the Cuban players, future major leaguers Tony González, Leo Cárdenas, and Cookie Rojas stood out, as did Venezuelan Elio Chacón, and Americans Jesse Gonder, Larry Novak, and Ted Wieand. Given this improvement and the new political atmosphere, attendance increased in 1959.

However, 1959 also saw growing unease by certain American players and International League team owners. American players were still well received and no particular hostility was displayed but the presence of armed revolutionaries, often at the field, was somewhat ominous.15 However, from a Cuban perspective, journalist Fausto Miranda noted “how different from the baseball with fans being frisked at the gates, or the afternoon when the students were clubbed on this very field”16 as had occurred recently under the Batista regime.

26th of July

Incidents at midseason reinforced these perspectives concerning the atmosphere surrounding the games. With the Rochester Red Wings in town for a weekend series, Cubans were preparing to celebrate the anniversary of the attack on the Moncada barracks, which took place on July 26, 1953, and marked the beginning of Castro’s insurrection. To begin the weekend, a two-inning exhibition game was planned prior to the Friday night game. With obvious political symbolism, a team of revolutionary leaders called “The Bearded Ones” (Los Barbudos), which included Camilo Cienfuegos at shortstop and Castro on the mound, played a team composed of military police. While the game was sheer entertainment and is recalled as a high point of the weekend’s activities, it demonstrates the strength of theatricality and baseball in Cuban political life.

The next night’s contest heightened concern about the Havana franchise. With the game running late, the stroke of midnight heralded the beginning of the 26th of July anniversary with riotous cheers and celebratory gunfire erupting from in and around the stadium. Rochester player/coach Frank Verdi was stuck by a falling bullet on the padding-lined hat he was smart enough to be wearing and Havana shortstop Leo Cárdenas was grazed on the shoulder.17 Neither was seriously hurt but the Rochester manager, Cot Deal, who had been ejected earlier in the game, pulled his team from the field and returned to the States the following day. The series was cancelled, the Sunday doubleheader forfeited, and an effort by Maduro was needed to keep the franchise in Cuba.18

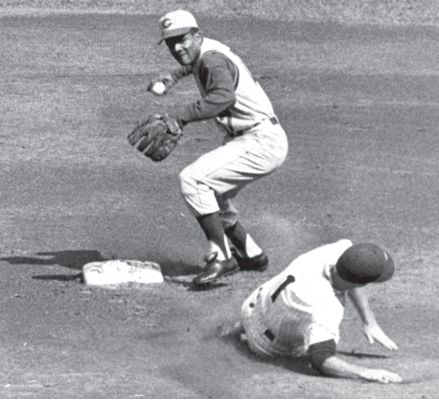

Elio Chacón Rodríguez was from Venezuela and was initially signed by Cincinnati in 1956 as a free agent, but did not make the majors until 1960. While with the Mets in 1962 he was famously involved in an outfield collision with outfielder Richie Ashburn who was shouting “I got it!” in English. Reportedly Ashburn switched to yelling “Yo la tengo!” instead and was promptly run over by Frank Thomas who had missed the discussion about the switch to Spanish. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Success

The Sugar Kings had a particularly strong defense—including a pitching staff bolstered by former major leaguers Wieand and Walt Craddock, younger Cubans Mike Cuellar and Raúl Sánchez, and Puerto Rican reliever Luis Arroyo—and finished 1959 at 80–73, nine games behind Buffalo but comfortably in third place. As a result, they were in the playoffs, during which they first defeated second-place Columbus in four games, then fourth-place Richmond in six games, winning the International League championship. The Richmond series exemplifies the defensive nature of the squad as Havana scored only 10 runs over six games. The Cuban newspaper, Revolución, had a picture of Castro in the victor’s dressing room with winning battery mates Sánchez and Enrique (Hank) Izquierdo.19

The Junior World Series against the Millers, the Red Sox affiliate and American Association champs, was scheduled to be three games in Minneapolis and four games in Havana, but with one rainout and an early chill in the forecast, it was decided to move the remaining games to Havana with the series tied at one game apiece.20

Championship

On October 2 both teams arrived in Havana to a rousing welcome but only one team had the expectation of a nation. That nation would not be disappointed. Games Three and Four were extra inning affairs both won by Havana. Game Three featured a home run by 20-year old Carl Yastrzemski of the Millers. Each game had a party-like atmosphere and the new government took every opportunity to share the spotlight. Castro threw out the ceremonial first pitch of Game Three. Several heads of state and dignitaries such as Che Guevera watched Game Four from designated box seats and Castro, blurring lines more than could be expected, sat in the dugout during the Sugar Kings’ Game Six loss. While no violence was reported, members of the Millers, including manager Gene Mauch, reported intimidation and generalized unease at the environment.21 Minnesota battled back to tie the series at three games heading into October 6 finale.

Game Seven, postponed one day due to rain, saw an overflow crowd of 35,000 including members of the inner circle of the new government. The final game was a gem with the Sugar Kings tying the score at two in the eighth inning and winning it in the bottom of the ninth in classic small-ball fashion: lead-off walk, sacrifice bunt, fly out, intentional walk, and bouncing grounder up the middle to score pitcher Sánchez with a head-first slide. Film footage of the winning score attests to what would be imagined: jubilation with fans, soldiers and players filling the field, and celebrating in front of the presidential box seats for hours. This was a moment of great success for an internationally diverse team paying temporary dividends to a government wanting to rally its people. The overall attendance of this seven game series was 103,808 but only 3,548 attended the two Minneapolis home games.22

1960 and the Move to Jersey City

As 1959 progressed, relations between Cuba and the United States deteriorated and by early 1960, the effects were being felt in the world of baseball. Jackie Robinson refused to attend an event for black athletes in Cuba,23 American players were returning early from their Cuban winter league teams,24 and the refusal of several Baltimore players to go to Cuba caused the cancellation of a preseason match in Havana between the Reds and Orioles.25 The International League granted long-time president Frank Shaughnessy power to remove the Sugar Kings from Havana at his sole discretion.26

The continued efforts of Maduro prevented an immediate reassignment so the Sugar Kings began 1961 in Havana. However, Maduro could not address external factors such as the Cuban government nationalizing parts of the sugar and other industries and the United States reducing the sugar quota, the amount of sugar purchased by the United States at a fixed price.27 As a result of this and other actions, the United States Secretary of State, Christian Herter, pressured MLB Commissioner Ford Frick who in turn pressured Shaughnessy to take action. The decision was then made to revoke the Havana franchise citing the “emergency” in Cuba and concern over the “safety and welfare” of personnel. Hasty meetings were arranged with representatives of the Reds and Sugar Kings but on an early July road trip through Miami the team was notified that they would be relocating to Jersey City, New Jersey. Bobby Maduro called the decision “completely outrageous” and bemoaned its calamitous effects on his personal finances and on the relations between the baseball communities of the two countries.28

Before the Miami series, Shaughnessy had contacted Jersey City Parks Commissioner Bernard Berry to discuss the lease of Roosevelt Stadium.29 Officials in Jersey City, seemingly enthralled with the idea of another chance at professional baseball, offered easy access and favorable terms to the stadium, and on July 8, the transfer of the franchise was announced. The first game was to be July 15, after the Miami series ended. Players were given a chance to go back to Cuba to bring their families.

Manager Tony Castaño, who had replaced Gómez at the beginning of the season, resigned from the team in protest and the Cuban government made clear their displeasure, but eleven Cuban players under contract made the decision to stay with Jersey City.30 For Cookie Rojas the choice was simple. “It wasn’t a hard decision for me, I wanted to play professional baseball, they didn’t allow professional baseball in Cuba, so I had to stay.”31 He went home to Cuba to collect his pregnant wife and young child and moved to New Jersey, as of yet never to return to Cuba.

The team was hastily named the Jerseys and early on July 15 arrived in Jersey City. The motorcade that took them to their first game at Roosevelt Stadium was greeted by cheers in “areas where Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Negro families predominate.” The first car of the motorcade held new and former manager Nap Reyes and the current Miss Jersey City.32

Reyes, a veteran of years playing in both countries, including a stint with the Jersey City Giants in 1942–43, was not fazed by being denounced by Castro for accepting the job, even when extra security was put in place for the team and police dispatched to the dugout.33

The Jerseys began their existence in fourth place but ended the year in fifth and out of the playoffs. The season ended with high expectations for 1961 but also clear concern over the poor attendance in what was increasingly a “Yankees-on-TV” town.34

1961

Despite free parking at Roosevelt Stadium, pledges of support from local officials and an appearance by actress Yvonne DeCarlo on opening day, attendance in the 1961 season was more disappointing than the previous year.35 In mid-May, with the Jerseys vying for first place, a Saturday game only drew 1,529, “including a few drunks who congregated in the rear of the Jersey dugout.”36

Nap Reyes, as he watched his team “march-funeral-style back to the dressing room” after losing a Labor Day doubleheader, summed up the sad end to the Sugar Kings in Jersey City with, “I’ve seen happier men dangling from the end of a rope.”37

On October 3 the decision that had long been rumored took place and the Jerseys were moved to Jacksonville and renamed the Suns. Bobby Maduro retained ownership and the team was now affiliated with the Cleveland Indians.38 While Maduro continued with Jacksonville, the revolution and the Jersey City experience left him in severe financial straits.39 After the 1965 season, he left the Suns and the last vestige of the Sugar Kings was gone.

Conclusion

Despite a major league stadium and support from the city, relocating to Jersey City was a bad and hasty move forced upon the franchise and Bobby Maduro. The support of the community was never there. While Toronto and Buffalo would regularly get crowds of 10,000 fans, the Jerseys barely got 1,000. Adding to attendance woes were the high operating costs in Jersey City, eventual loss of radio and TV revenue, and, not least, Maduro’s “growing, personal financial crisis.”40 If the Sugar Kings were allowed to stay in Cuba, would this have been a mechanism for better relations between the United States and Cuba? Probably not, but the question is worth asking.

Though the Sugar Kings had a sad ending, their years in Havana are quite uplifting. The drama created by a team that underperformed for five seasons and then won the Junior World Series during a year in which a revolution was occurring is an amazing story. The Sugar Kings were a team of destiny intertwined with something larger than themselves. Were they the best minor league baseball team in 1959? Probably not, but external developments created a much bigger stage on which they performed and triumphed.

It is ironic that a team embodying a shared aspect of distinct cultures became the object destroyed by those cultures. The Sugar Kings were a team that straddled eras, an experiment with one shining moment but unfortunately never given the chance to fulfill its potential. The individual who should be best remembered is the idealistic Maduro, who lost a great deal but stayed loyal to his beloved sport and team even after moving to Jersey City. The legacy of the Sugar Kings are also its players, especially Cuellar, González, Rojas, and Cárdenas, who took the drama embraced in 1959 and carried it through long and successful major league careers.

JOHN ROCKWELL HARRIS is a writer, photographer and producer of the B&H Photography Podcast. In addition to writing on baseball history, he has written extensively on photography and camera technology. His photographs have appeared in The New York Times and have been exhibited at the International Center of Photography, Museum of Modern Art, and Victoria & Albert Museum. A lifelong Indians fan, he had a short stint with the baseball team of his alma mater, Fordham University. John can be reached at harrisfoto@gmail.com or @jrockfoto10 on Twitter.

JOHN J. BURBRIDGE JR. is currently Professor Emeritus at Elon University where he was both a dean and professor. While at Elon he introduced and taught Baseball and Statistics. A native of Jersey City, he authored “The Brooklyn Dodgers in Jersey City” which appeared in the 2010 Baseball Research Journal. John has also presented at SABR conventions and the Seymour meetings. He is a lifelong New York Giants baseball fan (he does acknowledge they moved to San Francisco). The greatest Giants-Dodgers game he attended was a 1–0 Giants’ victory in Jersey City in 1956. Yes, the Dodgers did play in Jersey City in 1956 and 1957, as did the Havana Sugar Kings in 1960 and 1961.

Notes

1. Mark Rucker and Peter C. Bjarkman, SMOKE: The Romance and Lore of Cuban Baseball (Kingston, New York: Total Sports Illustrated. 1999).

2. Robert Gonzàlez Echevarría, The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (Oxford, Oxford University Press 1999), 90.

3. Gonzàlez Echevarría, 112–88.

4. http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/l/luquedo01.shtml.

5. Joseph Gerard, SABR Bioproject, “Mike Gonzalez,” http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/75c3d9b1.

6. http://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Florida_International_League.

7. Rory Costello, SABR Bioproject, “Bobby Maduro,” http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/c34ce106.

8. http://baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=dcl9fdbc.

9. http://www.milb.com/documents/2010/08/06/13100514/1/Cuba.pdf.

10.. http://history.com/this-day-in-history/castro-sworn-in.

11. http://www.coldwarstudies.com/2010/12/13/cold-war-havana-prelude-to-american-sanctions.

12. “Havana Team to Stay,” New York Times, April 24, 1959, 33.

13. Robert Gonzàlez Echevarria, Cuban Fiestas (New Haven, Yale University Press 2010), 205.

14. “Havana Baseball $20,000 Sweeter,” United Press International, April 29, 1959 as quoted in Rory Costello, SABR Bioproject, “Bobby Maduro,” http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/c34ce106.

15. Robert Gonzàlez Echevarría, Cuban Fiestas (New Haven, Yale University Press 2010), 204.

16. Fausto Miranda, Revolución, October 2, 1959 as quoted in Robert Gonzàlez Echevarria, The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (Oxford, Oxford University Press 1999), 341.

17. Robert Gonzàlez Echevarría, Cuban Fiestas (New Haven, Yale University Press 2010), 202.

18. Gonzàlez Echevarría, Cuban Fiestas, 202.

19. Gonzàlez Echevarría, Cuban Fiestas, 203.

20. “Cold Halts Junior Series,” New York Times, September 30, 1959, 45.

21. http://www.stewthornley.net/millers_havana.html.

22. http://www.stewthornley.net/millers_havana.html.

23. Robert González Echevarría, Cuban Fiestas (New Haven, Yale University Press 2010), 209.

24. González Echevarría, Cuban Fiestas, 209.

25. Robert González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (Oxford, Oxford University Press 1999), 345; and Milton H. Jamail, Full Count: Inside Cuban Baseball (Carbondale, Southern Illinois University Press 2000), 122.

26. González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana, 345.

27. González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana, 345.

28. Rory Costello, SABR Bioproject, “Bobby Maduro,” http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/c34ce106.

29. “Meeting is Planned,” New York Times, July 8, 1960, 24.

30. Joseph O. Haff, “Ex-Sugar Kings Get a Noisy Welcome in New Home,” New York Times, July 16, 1960, 11.

31. Jersey Journal (Jersey City, NJ), April 16, 1999, 7.

32. Joseph O. Haff, “Ex-Sugar Kings Get a Noisy Welcome in New Home,” New York Times, July 16, 1960, 11.

33. Joseph O. Haff, “Ex-Sugar Kings Get a Noisy Welcome in New Home,” New York Times, July 16, 1960, 11.

34. Howard M. Tuckner, “Jersey City Facing Loss of Ball Team,” New York Times, July 9, 1961, 51.

35. “Night Game With Buffalo to Start at 8,” Jersey Journal, April 18, 1961, 3.

36. Jersey Journal, May 13, 1961, 27.

37. Jersey Journal, September 5, 1961, 5.

38. “Franchise Shifted, Jerseys a Memory,” Jersey Journal, October 4, 1961

39. Rory Costello, SABR Bioproject, “Bobby Maduro,” http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/c34ce106.

40. Devine, Tommy, “Ultimatum by IL Directors Puts on Heat,” Miami News, June 7, 1961, 5B, as quoted in Rory Costello, SABR Bioproject, “Bobby Maduro,” http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/c34ce106.