The Sport of Courts: Baseball and the Law

This article was written by Ross E. Davies

This article was published in Fall 2009 Baseball Research Journal

What we have in this special edition of the Baseball Research Journal are four snapshots of events and personalities from the wide world of “baseball-and-the-law”:

What we have in this special edition of the Baseball Research Journal are four snapshots of events and personalities from the wide world of “baseball-and-the-law”:

- Roger Abrams on arbitration and the 1975 Andy Messersmith reserve-clause case;

- Samuel Alito on the Supreme Court’s 1922 decision in Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs — the original baseball antitrust-exemption case;

- a sketch I wrote of William R. Day, Supreme Court justice (1903–22) and arguably the most ardent baseball fan in the Court’s history.

- the late Gene Carney on the 1919 Black Sox investigation supervised by the law firm now known as Mayer Brown LLP;

- my study of Justice Harry Blackmun’s 1972 list of baseball greats in Flood v. Kuhn — the most recent Supreme Court decision upholding the baseball antitrust exemption; and

- Mark Armour on the attempt by two American League umpires, Bill Valentine and Al Salerno, to organize an umpires’ union in the 1960s.

Before enjoying these close-ups of baseball’s relations with the law, though, it might be worthwhile to step back for a moment and get a sense of just how big the big picture of “baseball-and-the-law” is. And it is indeed quite big. Consider, briefly, the length, breadth, and depth of the relationship between the two. (In order to tell a less-than-interminable tale, this paper tilts back and forth between recent years – evidence of the vibrancy of the baseball-law relationship today – and the late 19th and early 20th centuries – evidence that it has been vibrant for a long time – and deals only sketchily even with those periods. This should not be taken to mean that the baseball-law relationship was any less interesting at other times, or that there isn’t much more to be said about all times.1)

Length

As Professor Abrams, a leading law-and-baseball scholar,2 crisply and correctly puts it, the “relationship between baseball and the legal process dates from the earliest days of the organized game.” His evidence is truly foundational: in 1845, “when young men from New York City ferried across the Hudson River to Hoboken, New Jersey, to play the sport on the Elysian Fields cricket pitch; they signed a formal lease contract, paying seventy-five dollars for use of the field.”3 And what is a contract, after all, but “a promise or a set of promises for the breach of which the law gives a remedy, or the performance of which the law in some way recognizes as a duty”?4

Baseball and the law have been going steady ever since.

By the end of the 19th century and throughout the 20th century, baseball was frequently the subject of litigation (in federal,5 state,6 and municipal7 courts, and before arbitrators8); of legislation (in Congress,9 state assemblies,10 and town councils11); and of regulation (by presidents,12 governors,13 and mayors,14 and their minions15). That pattern has persisted, and perhaps even intensified, in the early years of the 21st century. In just the month before this article went to press, for example, courts issued reported opinions in 132 cases involving baseball in one way or another.16

Which brings us to breadth.

Breadth

The broad scope of baseball’s interaction with the law is revealed not only in the range of legal institutions at all levels of government that attend to baseball and baseball-related matters, but also in the numerous and colorfully various legal issues that arise in and around baseball. What follows is not an inventory or even an outline of those interactions, but, rather, a sampler of cases, statutes, regulations, and other forms of law, modern and not-so-modern, that highlight some of the directions in which baseball carries the law, and in which the law carries baseball.

Modern Times

Headline-grabbing modern examples of “baseball-and-the-law” come easily to mind.

In 2002, for example, it was a state court (the Superior Court of San Francisco County, California) that determined who owned Barry Bonds’s 73rd home run ball of the 2001 season. The judgment of the court was Solomonic: “plaintiff [Alex Popov] and defendant [Patrick Hayashi] have an equal and undivided interest in the ball. . . . In order to effectuate this ruling, the ball must be sold and the proceeds divided equally between the parties.”17 More recently, a federal court of appeals in the Midwest ruled that a fantasy baseball operator’s “first amendment rights in offering its fantasy baseball products supersede the players’ rights of publicity.”18 And it wasn’t that long ago (the late 1980s) that the fight between men referred to in judicial opinions as “Peter E. Rose” and “A. Bartlett Giamatti” was wending its way through state and federal courts in Ohio.19 Also in the late-1980s, it was at the hands of arbitrators (essentially, private judges created and empowered by contract20) that team owners learned that their exemption from federal antitrust law21 did not extend to federal labor law, and that they would not be permitted to collude in violation of a collective bargaining agreement to deprive free agents of a market for their services.22

Then there is the steroids scandal, much of which is being played out in the presence of judges, legislators, prosecutors, and grand juries. For the past several years, Congress, while considering such legislation as the “Clean Sports Act of 2005” and the “Professional Sports Integrity and Accountability Act” has been ferreting out the details,23 and urging the Department of Justice to investigate witnesses who might have lied to congressional committees.24 Meanwhile, in one federal court government agents investigating the scandal were recently ordered to return records improperly seized from drug test administrators,25 while in another court, proceedings are ongoing against Barry Bonds for allegedly false statements to a grand jury investigating unlawful steroids use.26 And so on ad nauseum.

And for every one of those famous bits of “baseball-and-the-law,” there are many more obscure developments – some numbingly routine, some highly technical, and some entertainingly odd or illuminating.

In the routine category, in September 2009, a New York state court decided the most recent in a long line of cases in which a spectator is injured by a foul ball and then sues the home team (and everyone else connected with the incident, the team, or the stadium). The spectator lost, as most spectators do, notwithstanding the sometimes tragic injuries they suffer.27 Similarly, it seems there is always litigation underway somewhere involving some aspect of the big-dollar, big-controversy business of stadium construction. In the summer of 2009, some of the action was in Miami-Dade County, where bonds used to build the home of the Florida Marlins were at issue,28 while in 2008 one developer was in court in Washington, DC, seeking to prevent the sale to a competitor of valuable real estate near the Nationals’ new stadium,29 and in 2007 a bankrupt subcontractor was suing the general contractor that had completed Citizens Bank Park for the Philadelphia Phillies in 2004.30 And the number of criminal cases involving defendants alleged to have worn a “baseball cap” or wielded a “baseball bat” is depressing.31

High technicality appropriately obscures some baseball cases, but there are a few, at least, that are important enough to merit attention despite the technical tedium. At the Supreme Court, for example, 2001 was a year of decisions of just that sort. Adding nuance to the scope of judicial review of labor arbitration decisions, the Court upheld the power of an arbitrator to deny a player’s claim (in particular, Steve Garvey’s for $3 million) from the fund established to compensate players for losses caused by owner collusion against free agents in the mid-1980s.32

And in a case brought by the Cleveland Indians (and supported by the Major League Baseball Players Association) the Court held that when a player is paid out of that fund, Social Security and federal unemployment taxes are to be paid by both the player and his employer (the team owner) at the rates applicable when the payout is made, not at the rate that would have applied if the player had been paid properly in the first place (back in the mid-1980s). The result? That should be obvious, because Social Security and unemployment tax rates have been rising for years: more taxes paid by both the player and the team owner.33

More entertainingly, and probably quite prudently, in May 2009, the Department of Homeland Security issued a Temporary Final Rule under which

The Coast Guard is establishing a temporary safety zone for the waters of the Allegheny River from mile marker 0.4 to mile marker 0.6, extending the entire width of the river. This safety zone is needed to protect spectators and vessels from the hazards associated with the Pittsburgh Pirates Fireworks Display. Entry into this zone is prohibited, unless specifically authorized by the Captain of the Port Pittsburgh or a designated representative.34

Apparently, errant baseballs striking fans are one thing (see discussion above), but errant flaming projectiles striking watercraft are something else entirely.

Even more clearly in the entertaining category is a 2009 case in which Samuel Steele (a songwriter) sued Turner Broadcasting System, Jon Bongiovi (leader of the rock-n-roll band Bon Jovi), and a host of other people and companies for copyright infringement. Steele claimed they had copied lyrics and music from “Man I Really Love This Team” – a “love anthem” he had written in honor of the Boston Red Sox – and used them in the Bon Jovi song “I Love This Town” and an associated TBS promotional video. Finding that “no reasonable juror . . . could find that the original elements of the Steele Song are substantially similar to the Bon Jovi Song or the TBS Promo,” the court ruled against Steele.

Perhaps more devastating to Steele than the legal humiliation was the artistic one. In the course of rejecting Steele’s claims, the court found that some of Steele’s lyrics were “too trite and common too warrant protection.” The court also explained that some of his lyrics could not be protected by copyright law because “common expressions and cliches are not copyrightable,” and noted in particular that “the fact that both songs rhyme ‘round’ with ‘town,’ is also commonplace as evinced by the fact that it is found in the popular children’s song ‘The Wheels on the Bus’.”35

Ouch. Nor is Steele the only frustrated baseball-song writer to have been disappointed in court recently. Jacob Maxwell (a songwriter ) sued Michael Veeck (executive director of the Fort Myers Miracle minor league baseball team) and a variety of other people and organizations over the rights to a theme song – “Cheer! The Miracle Is Here” – Maxwell had written for the team in 1993. During the 1993 season, Maxwell persistently requested that the team play the song at games (which it did) and pay him the agreed-to fee for the song (which it did not do). Eventually, Maxwell sued for copyright infringement. He lost, in part because he had been so laid-back about letting the Miracle play the song at games without paying him: by doing so he had given the team an “implied nonexclusive license” to play the song. The dispute must have taken the fun out of playing the song, though, because the Miracle used it for the last time on August 27, 1993.36

Illuminating use of baseball in the law sometimes occurs in cases in which neither the game nor the business is at issue.37 Consider, for example, Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s June 2009 dissent in Ricci v. DeStefano, an important civil rights case involving the testing and promotion of firefighters in New Haven, Connecticut. Ginsburg brought baseball into the picture ever so briefly but usefully in a footnote to her discussion of the limitations of written examinations as predicters of on-the-job performance:

[T]here is a difference between memorizing . . . fire fighting terminology and being a good fire fighter. If the Boston Red Sox recruited players on the basis of their knowledge of baseball history and vocabulary, the team might acquire [players] who could not bat, pitch or catch.38

In a more recent case (September 2009), the Township of Tinicum passed a law imposing a tax on all aircraft landing within its borders (some of the runways at Philadelphia International Airport are actually in Tinicum), and the U.S. Department of Transportation declared the law invalid. Tinicum appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, which ruled in favor of the Department of Transportation. In the course of his opinion for the court, Judge Michael Chagares explained the meaning of the phrase “only if” (the words appeared in the statute empowering the Department of Transportation to invalidate Tinicum’s tax law):

The phrase “only if” describes a necessary condition, not a sufficient condition. . . . A necessary condition describes a prerequisite. . . . For example, making the playoffs is a necessary condition for winning the Major League Baseball World Series because a team cannot win the World Series if it does not make the playoffs. Using the “only if” form: a team may win the World Series only if it makes the playoffs. But, a team’s meeting the necessary condition of making the playoffs does not guarantee that the team will win the World Series.39

There is no shortage of similar exercises, including Judge Janice Rogers Brown’s dissent in an employment discrimination case in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, in which she contrasted Randy Johnson’s poor performance as a batter with his extraordinary career as a pitcher to make the point that “often even a serious deficiency can be offset by other compelling considerations.”40 And Vice Chancellor John W. Noble’s opinion in a surety bond case in the Delaware Chancery Court, in which he explained the difference between having one’s debt rated by Standard & Poor’s and using Standard & Poor’s guidelines to conduct one’s own rating:

An analogy to the game of baseball illustrates the importance of this distinction. A pitch may be belt-high, over the middle of the plate, thus, satisfying all objective criteria for classification as a strike. See Rule 2.00, Official Rules of Major League Baseball (“The strike zone is that area over home plate the upper limit of which is a horizontal line at the midpoint between the top of the shoulders and the top of the uniform pants, and the lower level is a line at the h[o]llow beneath the knee cap.”). That pitch, however, for purposes of the game, is not a strike unless and until the home plate umpire makes the call. See id. (“A strike is a legal pitch when so called by the umpire, which . . . (b) [i]s not struck at, if any part of the ball passes through any part of the strike zone.”).41

These days, its seems, where goes baseball, there goes the law, and vice versa.

The Old Days

But was it ever any different? Was there, long ago, a time when baseball had no use for the law? Professor Abrams has answered that question with an authoritative No.42 Moreover, while the number of baseball-related lawsuits has certainly risen over the years (a subject touched on in the “Depth” section below), variety seems to have been a hallmark of the connections between baseball and the law from the beginning.43 The Supreme Court, for example, heard its first baseball case in 1884 – a dispute over a patent relating to the manufacture of baseballs.44 By then, Congress and the lower federal and state courts had for years been hearing testimony about (and commenting on) baseball in contexts ranging from patent law,45 to notes and bonds issued by the U.S. Treasury,46 to railroad accidents,47 to the treatment of veterans,48 to beer-fueled violence,49 to church governance,50 to the reserve clause,51 to pick-pocketing.52

But was it ever any different? Was there, long ago, a time when baseball had no use for the law? Professor Abrams has answered that question with an authoritative No.42 Moreover, while the number of baseball-related lawsuits has certainly risen over the years (a subject touched on in the “Depth” section below), variety seems to have been a hallmark of the connections between baseball and the law from the beginning.43 The Supreme Court, for example, heard its first baseball case in 1884 – a dispute over a patent relating to the manufacture of baseballs.44 By then, Congress and the lower federal and state courts had for years been hearing testimony about (and commenting on) baseball in contexts ranging from patent law,45 to notes and bonds issued by the U.S. Treasury,46 to railroad accidents,47 to the treatment of veterans,48 to beer-fueled violence,49 to church governance,50 to the reserve clause,51 to pick-pocketing.52

So, stepping back a century or so to the early decades of baseball-law interaction, it should come as no surprise that in the early years, baseball and the law were making headlines together, with stories to match our modern examples.

There were, at least in retrospect, two especially big cases. First, there was the Black Sox prosecution, in which eight Chicago White Sox players were indicted in 1920 and reindicted in 1921 for conspiring to throw the 1919 World Series between the White Sox and the Cincinnati Reds. They were tried before a jury in Illinois state court, and acquitted. But they were punished anyway, when baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis banned them from major league baseball for life.53 Second, at about the same time, there was Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs,54 which was both the first baseball antitrust case to reach the Supreme Court of the United States and the culmination (or, really, the anti-climax) of the war between the upstart Federal League and the established American and National Leagues. This case receives a thorough treatment in Justice Alito’s article.

Other interesting and widely-followed cases also arose in the early years, including one in which Kenesaw Mountion Landis was the accused, rather than the judge. In 1921, as the Federal Baseball case was making its way from the lower federal courts to the Supreme Court,55 Landis was serving both as a federal judge in Chicago and as the first commissioner of major league baseball. As a result, he found himself on both sides of the legal process – meting out justice in his own courtroom56 and feeling its bite in Congress. On February 2, Congressman Benjamin Welty of Ohio, introduced a resolution in the House of Representatives calling for an investigation of the legality of Landis’s dual office-holding.57 On February 14, Welty proposed impeaching Landis, even though Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer had determined that no law prevented Landis from holding both jobs at the same time.58 “The most general opinion,” reported the New York Times, “is that Judge Landis has violated no law, but he is criticised on the ground that he has lowered the standard of the bench and legal ethics by accepting the position of baseball arbiter.”59 On February 21, the House Judiciary Committee held a hearing on the Landis impeachment, during which his judgment and ethics were mightily abused,60 and Welty submitted his proposed impeachment:

I impeach Kenesaw M. Landis as district judge of the United States for the Northern District of Illinois, . . . as follows:

First. For neglecting his official duties for another gainful occupation not connected therewith.

Second. For using his office as district judge of the United States to settle disputes which might come into his court as provided by the laws of the United States.

Third. For lobbying before the legislatures of the several States of the Union to procure the passage of State laws to prevent gambling in baseball, instead of discharging his duties as district judge of the United States.

Fourth. For accepting the position as chief arbiter of disputes in baseball associations at a salary of $42,500 per annum while attempting discharge the duties as a district judge of the United States which tends to nullify the effect of the judgment of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia and the baseball gambling indictments pending in the criminal courts of Cook County, Ill.

Fifth. For injuring the national sport of baseball by permitting the use of his office as district judge of the United States, because the impression will prevail that gambling and other illegal acts in baseball will not be punished in the open forum as in other cases.

Wherefore said Kenesaw M. Landis was and is guilty of misbehavior as such judge and of high crimes and misdemeanors in office.61

With the end of the congressional session approaching, the judiciary committee failed to come to a conclusion on the Landis impeachment, but members of the committee did manage to leak to the media their intense hostility to Landis’s dual office-holding.62 Welty’s move to impeach Landis fizzled later in 1921, probably because what Landis was doing was indeed not prohibited by any controlling legal authority, even if it was shameful, and therefore could not provide the basis for impeachment (in addition, Welty had failed to gain reelection to the House, and so was not available to carry the torch).63 But other legislators took up the cause.64 In addition, the American Bar Association censured Landis,65 and the news media kept the issue in the public eye and some editorialized against him.66 Eventually, Landis gave up his judgeship, sending his resignation to President Warren G. Harding on February 18, 1922. Ironically, Landis’s stated reason for quitting was closely related to the concern underlying the first count of Welty’s impeachment. In his statement to the press, Landis said, “There aren’t enough hours in the day for me to handle the courtroom and the various other jobs I have taken on. . . . I am going to devote my attention in the future entirely to baseball.” 67 Landis insisted to the end that he would not be pressured into resigning his judgeship.68 Nevertheless, his case certainly appears to be a good example of the power of threatened or initiated legal proceedings to inspire an opponent to do what one seeks, even without seeing a case through to judgment.

In 1901 and 1902, in perhaps the most famous celebrity-player case of the early 20th century, the Philadelphia Phillies pursued one of their own star players in courthouses from eastern Pennsylvania to northern Ohio. In the wake of a salary dispute in 1900 with the Phillies of the National League, second baseman Napoleon Lajoie left the team to sign a contract with Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics in the then-new American league.69 Lajoie enjoyed a brilliant 1901 season with the Athletics,70 while the Phillies’ high-profile lawsuit seeking an injunction that would force him back into the fold slowly made its way through the Pennsylvania court system.71 When the Phillies finally prevailed in the Pennyslvania Supreme Court in April 1902,72 it was front-page news.73 But it was a fruitless victory. Lajoie promptly signed with the Cleveland Bluebirds of the American League,74 and when the Phillies sought to enforce their injunction in Ohio, an Ohio federal court refused to hear the case and an Ohio state court held that Lajoie was free to play for any team willing to employ him, or at least any Ohio team.75 (An early example, perhaps, of the home field advantage in baseball-and-the-law.76)

In 1901 and 1902, in perhaps the most famous celebrity-player case of the early 20th century, the Philadelphia Phillies pursued one of their own star players in courthouses from eastern Pennsylvania to northern Ohio. In the wake of a salary dispute in 1900 with the Phillies of the National League, second baseman Napoleon Lajoie left the team to sign a contract with Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics in the then-new American league.69 Lajoie enjoyed a brilliant 1901 season with the Athletics,70 while the Phillies’ high-profile lawsuit seeking an injunction that would force him back into the fold slowly made its way through the Pennsylvania court system.71 When the Phillies finally prevailed in the Pennyslvania Supreme Court in April 1902,72 it was front-page news.73 But it was a fruitless victory. Lajoie promptly signed with the Cleveland Bluebirds of the American League,74 and when the Phillies sought to enforce their injunction in Ohio, an Ohio federal court refused to hear the case and an Ohio state court held that Lajoie was free to play for any team willing to employ him, or at least any Ohio team.75 (An early example, perhaps, of the home field advantage in baseball-and-the-law.76)

Then as now, for every celebrated case there were many less-noticed ones, some interesting or important or both, some not so much. Here are just a few examples from a variety of areas of law, presented in a the question-and-answer format that will be familiar to anyone who was ever an aspiring lawyer studying for the bar exam. Some (but almost certainly not all) of these cases might have been familiar to the lawyers who served on the House judiciary committee or represented the Black Sox, the leagues, Lajoie, the Phillies, or other players in the early world of baseball-and-the-law:

Customs (imports and exports)

Is a baseball a toy?

No: “[B]aseball, a development of the schoolboy game of ‘one old cat,’ . . . [is a] game[] played by and eminently fitted to amuse children. . . . In the popular mind, however, . . . balls and bats . . . are not regarded as toys, for the simple and sensible reason that they are not the implements of games which are exclusively the diversions of children.”77

Evidence

Is a dislike for baseball evidence of insanity?

No: The fact that an individual “spoke disparagingly of baseball games and advised [someone] not to attend them” was “valueless and without weight as a basis for the opinion that” the speaker “was mentally incapable of making [a] will.”78

Is associating with a professional baseball player evidence of sanity?

No: Lulu Kennedy was tried for the murder of her husband, Philip Kennedy. Her defense was insanity. She was convicted. At the trial, the prosecution presented evidence that Lula had socialized with “one Case Patten, a professional baseball player” during the summer of 1900, before her marriage to Philip.79 (By the time of the trial, Patten was pitching for the Washington Senators.80) When Lulu appealed her conviction to the Missouri Supreme Court, the prosecution attempted to justify the presentation of evidence about her association with Patten by claiming it helped “to show she was perfectly rational, and that her conduct was that of a sane, and not an insane, person, as the defendant intimated she was.” The court did not believe it, ruling that the prosecution’s explanation was “absolutely untenable, for the record shows that it was not offered for any such purpose, but was offered for the sole purpose of besmirching defendant’s character,” and reversing Lulu’s conviction.81

Crime

Is a baseball bat a deadly weapon?

Maybe: “An instrument may or may not be a deadly weapon, depending on the manner in which it is used. It is probable that a riding-whip should not be so regarded. A base-ball bat, if viciously used, probably should be.”82

And maybe not: “A baseball bat is not per se a deadly weapon, and especially is it not a deadly weapon when considered without reference to its use.”83

Is it lawful to punch the umpire over “a decision unpopular among the partisans of one baseball team in a match”?

No: “The witnesses in the case are not in accord on the exact details of the affair, which culminated in a blow . . . that knocked down and broke the nose of a baseball umpire named Kerin, but there is nothing in the record throwing the least doubt on the fact that the blow was given in anger and wholly without legal justification. . . . The penalty [a $75 fine] was by no means unduly severe for the offense. . . . The conviction seems to us to have been justifiable and the penalty light, and the judgment is affirmed.”84 Nor is it lawful to shoot the umpire in a dispute over the score of a game.85

Criminal procedure

During a capital murder trial, may the “sheriff and one of the officers sworn to take charge of the jury [take] them to a baseball game, where there were some manifestations by people present well calculated to be interpreted by the jury as” encouragement to convict the accused?

No: “If it can be said that such gross misconduct on the part of a jury as took place upon the trial of this case can be passed over as not prejudicial to the accused, . . . the constitutional right to a trial by jury with substantially the common-law safeguards to prevent a miscarriage of justice, must be considered as having been effectually laid aside.”86

Morality (blue laws)

May baseball be played on Sunday, in 1900?

Yes, at least in Missouri: According to the Supreme Court of Missouri, interpreting a general statute that says, “Every person who shall be convicted of horse racing, cock fighting or playing at cards or games of any kind, on the first day of the week, commonly called Sunday, shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and fined not exceeding fifty dollars” to apply to playing baseball would “impair [citizens’] natural rights to enjoy those sports or amusements that are . . . neither immoral, nor hurtful to body or soul.” And so the court concluded that unless the state legislature passes a law explicitly prohibiting baseball on Sundays, “there is no law in this state which prevents playing a game of baseball on Sunday.”87

And no, at least in Michigan: “What is the legal character of the game of baseball played upon the Sunday in question?” the Supreme Court of Michigan asked itself. It answered, a Sunday “game of baseball was a breach of the peace” under a state statute “which imposes a penalty of not to exceed $10 for such offense.” 88

Torts

Is baseball a nuisance?

Yes, if players and spectators don’t behave: When a baseball game is carried on under the following conditions, the neighbor of a baseball diamond has a valid nuisance claim: “(1) The driving of the balls upon [the neighbor’s] grounds, and the consequent trespassing upon his grounds to recover the balls, by which his use of his grounds is rendered dangerous, his peace and quiet interfered with, and his property destroyed. (2) The noise occurring in the game itself, by the shouts of the players and spectators, and the loud, profane, and obscene language used by the players or spectators, and audible at his residence, together with the noise of fights and brawls during the games. (3) The . . . collection of large numbers of idle and disorderly persons in the neighborhood of the grounds, and of [the neighbor’s] house, while the games are in progress, which crowds, by their noise, vile language, and behavior, disturb the peace and quiet of the neighborhood, and subject complainant and other residents to insults and abuse, if they venture from their homes.”89

And no, if players and spectators do behave: “This court takes judicial notice of the fact that the game of baseball, when properly conducted, is an innocent public amusement, and constitutes the most popular and entertaining public pastime or sport of the American people. It is known from one end of our country to the other as the great American game, and is patronized by all classes, conditions, and sexes of our people, both old and young.”90

Is a fan struck by a foul ball entitled to compensation?

Rarely: As the parties agreed in the 1913 case of Crane v. Kansas City Baseball & Exhibition Co., “Baseball is our national game, and the rules governing it and the manner in which it is played and the risks and dangers incident thereto are matters of common knowledge.” And one of those risks, the court ruled, is being injured by a foul ball, especially when sitting in seats not screened-off from the field of play.91

Takings

Must the state pay if it quarters its militia on a baseball field?

Maybe: Because “It is for the state, in its sovereign capacity, to determine whether compensation will be made out of its treasury,” even when “two regiments took possession of the grounds or park of the appellee league ball club, occupied the same as and for an encampment ground, and remained there for a period of 20 days. The possession of the park was taken, and the troops encamped therein, without the knowledge or consent of the appellee club, the owner thereof. . . . [And] the militiamen, while in possession of the park, dug holes in the baseball diamond, drove horses pulling heavy caissons on and across the bicycle track, and broke down or damaged the turnstiles, ticket boxes, chairs, benches, etc., belonging to the club, causing injury and damage to the park and to the property of the club in the aggregate sum of $2,352.05.”92 (In this case, which arose out of the famous Pullman labor strike of 1894, the Cubs were in fact awarded $2,000.93)

Intellectual property

Is the curve ball patentable?

No: “It is . . . an art only in the sense that one speaks of the art of painting, or the art of curving the thrown baseball. Such arts, however ingenious, difficult, or amusing, are not patentable within any statute of the United States.”94

In those days as well, it seems, where went baseball, there went the law.

Depth

The depth of a relationship – its “secret, mysterious, unfathomable . . . inmost . . . part”95 – is not as easily established as its duration (just look at a clock or calendar) or the diversity of activities it involves (just look at an inventory, or at least a representative sampler). Instead of simply measuring, we must observe and infer. To that end, what follow are two sets of data – one numerical, one anecdotal – that might lend support to an inference that the relationship between baseball and the law is more than casual. First, the by-the-numbers look compares the frequency with which baseball has appeared in some legal contexts to the frequency with which other major sports have appeared in those same contexts. Second, the anecdotal approach presents a few of the many law-to-baseball and baseball-to-law crossover stories, with an eye to exhibiting just a little bit of the persistence and prominence of these sorts of connections.

By the Numbers

All sports have some level of engagement with the law. There are stories to be told about “basketball and the law,”96 “football-and-the-law,”97 “golf-and-the-law,”98 “soccer-and-the-law,”99 even “bocci-and-the-law.”100 But is any sport as engaged with the law as baseball is? Overall, the results of the simple exercises summarized below suggest that the answer is No: nothing in the law of sport matches the frequency of baseball’s interaction with institutions of the law or the tendency of lawmakers who speak of sports to speak in terms of baseball. This is not to say, however, that baseball has a corner on the legal mind. In some contexts, sports other than baseball are the leading figures. But even where baseball is not at the top, it tends to be close to it.

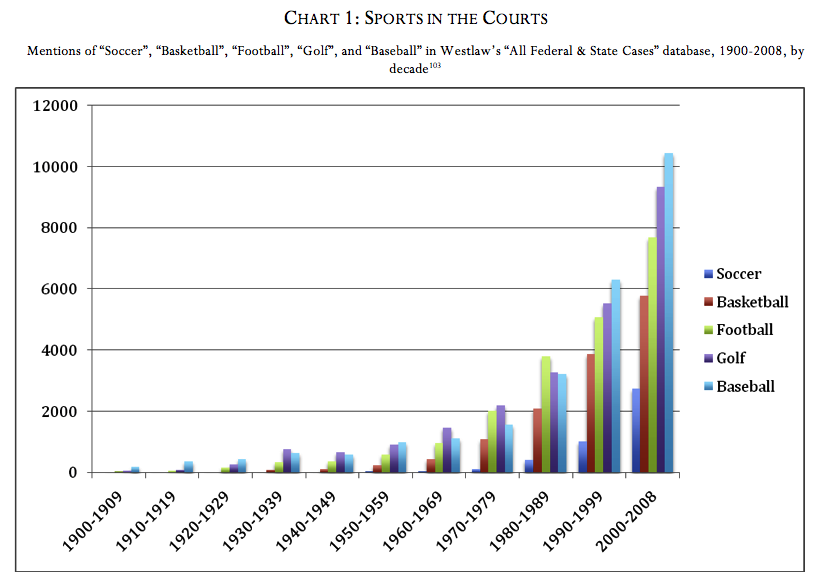

Consider first the frequency with which baseball comes up in judicial opinions in Westlaw’s widely-used “All Federal & State Cases” database,101 compared with the frequency of mentions of other major sports with the most plausible claims to compete with baseball for “national pastime” status – basketball, football, golf, and soccer.102 During the 20th century, there were decades when golf or football appeared in more judicial opinions than did baseball, but baseball was always one of the top two or three sports in the courts, and in recent years the trend has been decidedly in baseball’s favor. And only baseball can claim that on average, every working day of the past 100 years witnessed yet another case in which baseball played a part of some sort:

Chart 1: Sports in the Courts

Mentions of “Soccer”, “Basketball”, “Football”, “Golf”, and “Baseball” in Westlaw’s “All Federal & State Cases” database, 1900-2008, by decade103

Table 1: Sports in the Courts

Mentions of “Soccer”, “Basketball”, “Football”, “Golf”, and “Baseball” in Westlaw’s “All Federal & State Cases” database, 1900-2008, by decade

|

|

Soccer |

Basketball |

Football |

Golf |

Baseball |

|

1900-1909 |

0 |

2 |

43 |

57 |

190 |

|

1910-1919 |

2 |

5 |

50 |

86 |

358 |

|

1920-1929 |

5 |

20 |

154 |

266 |

428 |

|

1930-1939 |

6 |

84 |

329 |

766 |

633 |

|

1940-1949 |

19 |

110 |

366 |

655 |

581 |

|

1950-1959 |

24 |

234 |

583 |

902 |

996 |

|

1960-1969 |

42 |

440 |

966 |

1468 |

1110 |

|

1970-1979 |

123 |

1088 |

2020 |

2182 |

1576 |

|

1980-1989 |

416 |

2084 |

3805 |

3266 |

3221 |

|

1990-1999 |

1024 |

3872 |

5077 |

5537 |

6293 |

|

2000-2008 |

2752 |

5787 |

7675 |

9334 |

10433 |

|

TOTAL |

4413 |

13726 |

21068 |

24519 |

25819 |

Certainly, these are rough and gross measures that capture some irrelevancies for every sport (as are all the measures used below), but the idea is only to make a rough and gross point: that the judicial system deals with and speaks of baseball more than it does any other sport.

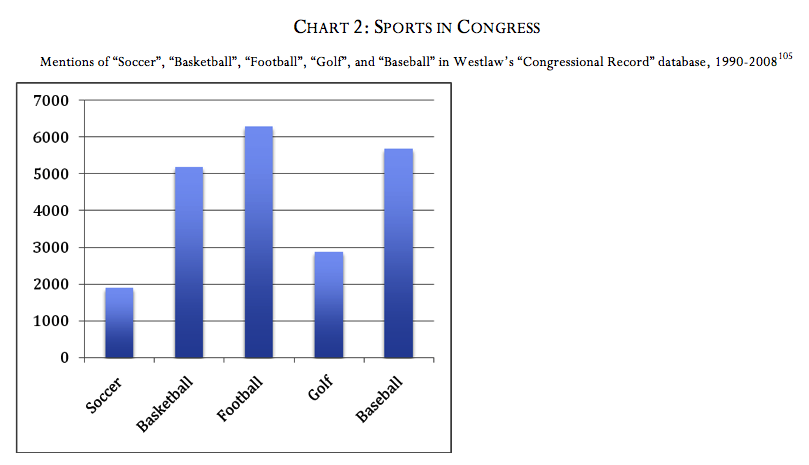

While baseball dominance in the courts seems pretty obvious, at least these days, the picture in the other great American law-making and law-enforcing institutions – legislatures and executives – is not so clear. For the past couple of decades, rates of major-sports mentions in Congress and by the President (the only institutions and the only period for which data across comparable institutons is consistently and conveniently available), suggest that while baseball might be the clear leader in the courts, football has a plausible claim to at least a share of the top spot in the other branches of government. In the Congressional Record (“the official record of the proceedings and debates of the United States Congress”104), football is the clear leader since 1990, exceeding baseball by more than 600 mentions, or almost 11%:

Chart 2: Sports in Congress

Mentions of “Soccer”, “Basketball”, “Football”, “Golf”, and “Baseball” in Westlaw’s “Congressional Record” database, 1990-2008105

Table 2: Sports in Congress

Mentions of “Soccer”, “Basketball”, “Football”, “Golf”, and “Baseball” in Westlaw’s “Congressional Record” database, 1990-2008

|

Soccer |

Basketball |

Football |

Golf |

Baseball |

|

1895 |

5187 |

6285 |

2885 |

5679 |

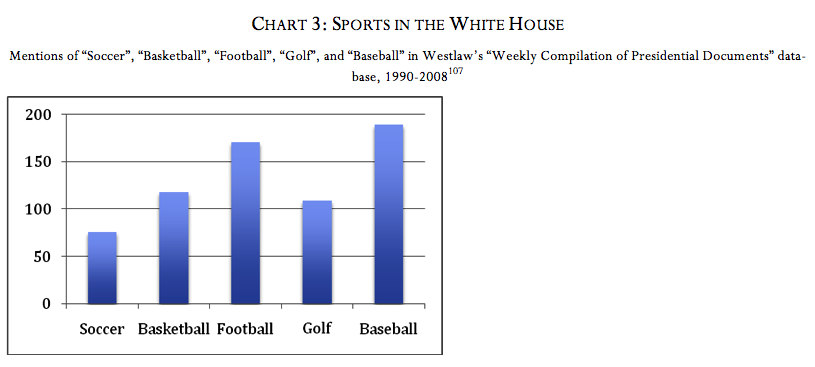

On the other hand, in the Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents (“the official publication of presidential statements, messages, remarks, and other materials released by the White House Press Secretary”106), baseball is the clear leader since 1990, exceeding football by 18 mentions, or almost 11% (albeit on a much smaller base):

Chart 3: Sports in the White House

Mentions of “Soccer”, “Basketball”, “Football”, “Golf”, and “Baseball” in Westlaw’s “Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents” database, 1990-2008107

Table 3: Sports in the White House

Mentions of “Soccer”, “Basketball”, “Football”, “Golf”, and “Baseball” in Westlaw’s “Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents” database, 1990-2008

|

Soccer |

Basketball |

Football |

Golf |

Baseball |

|

76 |

118 |

171 |

109 |

189 |

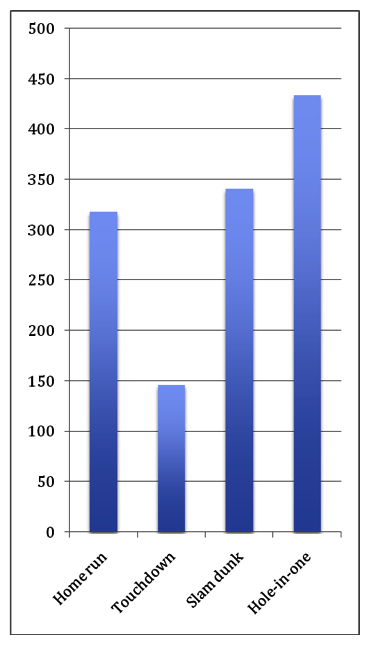

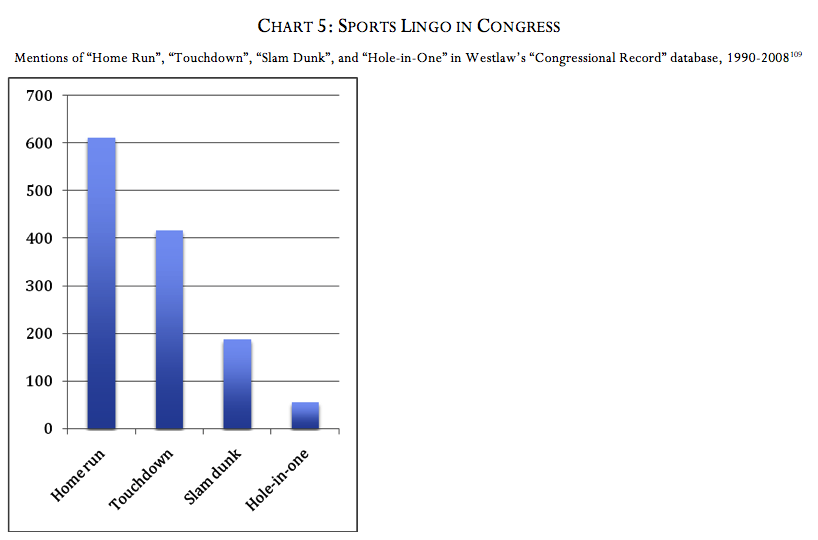

Approaching the same sports (except soccer, which is not a good fit in this context) in the same databases from a slightly different angle yields similar results. The angle is the use of the language of sport. A few quick looks in that direction suggest that while in general baseball comes up in more cases than do other sports, judges writing opinions are more likely to use the language of golf or basketball, while legislators and presidents are more inclined to speak the language of baseball (again, the measures are rough, but so are the points to be made):

Chart 4: Sports Lingo in the Courts

Mentions of “Home Run”, “Touchdown”, “Slam Dunk”, and “Hole-in-One” in Westlaw’s “All Federal & State Cases” database, 1990-2008108

Table 4: Sports Lingo in the Courts

Mentions of “Home Run”, “Touchdown”, “Slam Dunk”, and “Hole-in-One” in Westlaw’s “All Federal & State Cases” database, 1990-2008

|

Home run |

Touchdown |

Slam dunk |

Hole-in-one |

|

318 |

146 |

341 |

434 |

Chart 5: Sports Lingo in Congress

Mentions of “Home Run”, “Touchdown”, “Slam Dunk”, and “Hole-in-One” in Westlaw’s “Congressional Record” database, 1990-2008109

Table 5: Sports Lingo in Congress

Mentions of “Home Run”, “Touchdown”, “Slam Dunk”, and “Hole-in-One” in Westlaw’s “Congressional Record” database, 1990-2008

|

Home run |

Touchdown |

Slam dunk |

Hole-in-one |

|

611 |

417 |

188 |

55 |

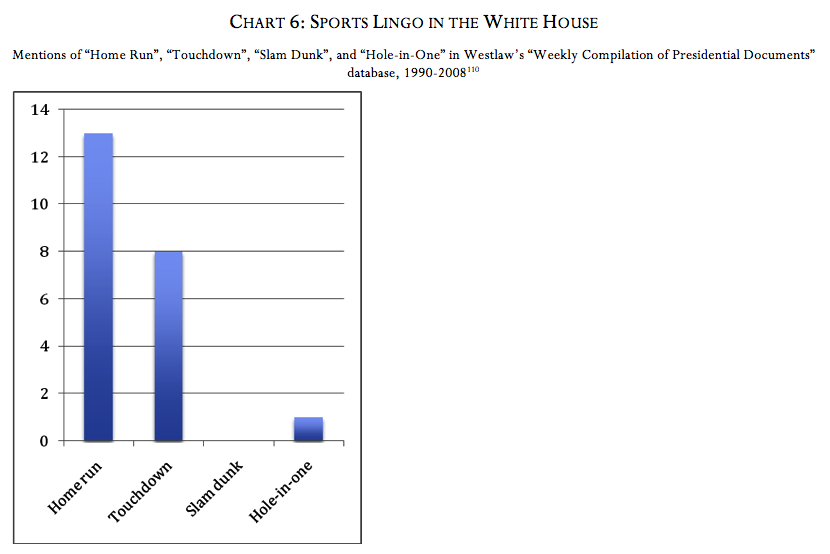

Chart 6: Sports Lingo in the White House

Mentions of “Home Run”, “Touchdown”, “Slam Dunk”, and “Hole-in-One” in Westlaw’s “Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents” database, 1990-2008110

Table 6: Sports Lingo in the White House

Mentions of “Home Run”, “Touchdown”, “Slam Dunk”, and “Hole-in-One” in Westlaw’s “Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents” database, 1990-2008

|

Home run |

Touchdown |

Slam dunk |

Hole-in-one |

|

13 |

8 |

0 |

1 |

Baseball does, however, appear to enjoy overwhelming priority when the subject is failure. Perhaps because there is no moment in other sports as distinctively and individually disappointing as a third strike in baseball, “three strikes” appeared in more than 10,000 judicial opinions from 1990 to 2008.111 Or perhaps this is because bad things in law tend to occur in threes rather than in, for example, twos (two balls in play and you’re out in golf112), fours (four downs and you’re out in football), or sixes (six fouls and you’re out in basketball113). On the other hand, there are the three-second rules in basketball.114 In any event, many of the “three strikes” mentions in judicial opinions can be attributed to “three strikes” laws designed to penalize repeat criminal offenders, but that merely points to the possibility that legislators, like judges, are comfortable with baseball’s definition of failure. And a quick look at the language of federal legislators lends some credence to that supposition: “three strikes” appeared 374 times in the Congressional Record from 1990 to 2008.115 On the other hand, “three strikes” appears nowhere in the Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents for the same period.116

None of this, of course, is direct proof of a deep relationship baseball and the law. But it does appear to be the case that there is more of baseball in the law than there is of any other major sport. So, if any sport is entwined deeply with the law, it is in all likelihood baseball.

By the Anecdotes

In the introduction to their book Baseball and the American Legal Mind, professors Spencer Waller, Neil Cohen, and Paul Finkelman rightly observe that “[g]iven the extensive parallels between legal culture and baseball culture, the breadth and depth of the baseball/law nexus is only to be expected.”117 And there are probably as many intersections as there are parallels. The law-to-baseball and baseball-to-law crossover stories sketched below are a small subset of the varied intersectional episodes that fill the history “baseball-and-the-law.” They are grouped here, old with new, to make the point that while each of these intimacies may stand alone, each is also an element of a longstanding and varied relationship.

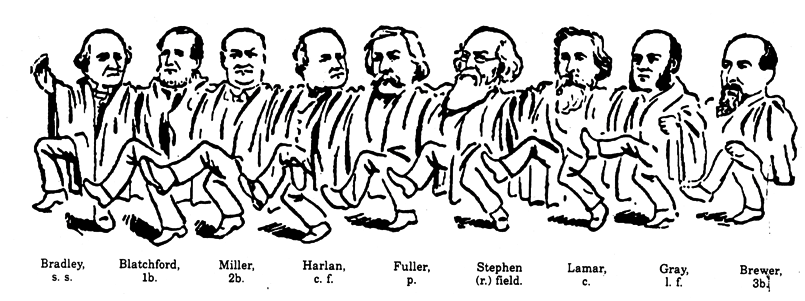

Media Darlings

Newspapers have long been fascinated by quirky connections between baseball and the law, and have played their own part in creating and highlighting them. One of the most superficially obvious – at least since 1869, when Congress increased the number of justices on the Supreme Court from eight to nine118 – has been the fact that a complete Supreme Court and a complete baseball team each has nine members. Opportunities to portray the Justices as “members of the great judiciary baseball team”119 have been difficult to resist. On February 5, 1890, for example, the New York Morning Journal portrayed the Supreme Court (which had celebrated its centennial the night before) as a dancing baseball team under the headline, “The United States ‘Nine’,” and assigned to each member of the Court a position:

Left to right, Justices Joseph P. Bradley (shortstop), Samuel Blatchford (first base), Samuel F. Miller (second base), and John Marshall Harlan (center field), Chief Justice Melville W. Fuller (pitcher), and Justices Stephen J. Field (right field), Lucius Q.C. Lamar (catcher), Horace Gray (left field), and David J. Brewer (third base).

The most famous and durable modern manifestation of this impulse appeared in the New York Times on April 5, 1979 – Robert M. Cover’s “Your Law-Baseball Quiz,” in which he used comparisons with individual ballplayers to characterize the work of individual Justices.120 Today, Cover’s project is being ably carried on by Professor Jerry Goldman at his “Oyez Baseball” website.121

On an equally obvious but more substantial note, the “National Commission” created as part of the 1903 peace agreement between the National League and the American League was – or was supposed to be – the final arbiter of inter-team and inter-league disputes.122 Sort of like a court of last resort.123 And so it should come as no surprise that in newspapers of the time it was “frequently referred to as the supreme court of baseball”124 or “the ‘supreme court’ of organized baseball.”125

Role Reversals

From time to time professionals in the field of baseball or the law will do more than merely express an interest in the other field; instead they will go to work in it. When these adventurers are successful in their first chosen field and then proceed to succeed in the other as well, the crossover connection often receives public notice.

Among the prominent examples from the early 20th century are John Tener and Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

Tener was a good pitcher. In 1885, he played for the Haverhill, Massachusetts team in the New England League, and then very briefly for the Baltimore Orioles. Early in 1888 he signed with the Chicago White Stockings (now the Cubs) and compiled a 22-20 record over the next two seasons. His last year as a player was 1890, with the Pittsburgh Burghers of the short-lived Players’ League. Tener settled in Pittsburgh, and after a successful career in business, launched an even more successful career in politics.126 In 1908 he won election to the U.S. House of Representatives, where the newspapers promptly picked up on his baseball past. The fact that the founding president of the New England League, William H. Moody,127 was by then another baseball-to-law crossover phenomenon made the story all the more appealing. As the Philadelphia Inquirer reported (with a few inaccuracies) on December 12, 1908,

Tener was a good pitcher. In 1885, he played for the Haverhill, Massachusetts team in the New England League, and then very briefly for the Baltimore Orioles. Early in 1888 he signed with the Chicago White Stockings (now the Cubs) and compiled a 22-20 record over the next two seasons. His last year as a player was 1890, with the Pittsburgh Burghers of the short-lived Players’ League. Tener settled in Pittsburgh, and after a successful career in business, launched an even more successful career in politics.126 In 1908 he won election to the U.S. House of Representatives, where the newspapers promptly picked up on his baseball past. The fact that the founding president of the New England League, William H. Moody,127 was by then another baseball-to-law crossover phenomenon made the story all the more appealing. As the Philadelphia Inquirer reported (with a few inaccuracies) on December 12, 1908,

One touch of baseball makes the whole world kin. Representative-elect John K. Tener, of the Twenty-fourth Pennsylvania district, was a noted baseball player in his days, winning a national reputation as a pitcher under “Pop” Anson on the old Chicago White Sox.

Today he visited Washington for the first time since playing here with the White Sox in 1889, and, of course, strolled up to the Capitol to look over the Congressional diamond, where he will perform when the Sixty-first Congress assembles next year. He fell into the obliging hands of John Williams, file clerk of the House, who introduced him to Uncle Joe Cannon, Vice President-elect Sherman, Representative John Dalzell and other stars of the House, who extended the right hand of fellowship to the six-foot-four member-elect. Incidentally Mr. Tener happened to mention that in the days of his baseball glory he once spent some time in coaching a famous amateur team at Haverhill, Mass., of which one William H. Moody, now a justice of the Supreme Court, was an enthusiastic abd valued member. He suggested that he would like to renew his acquaintance with Moody, and asked John Williams if he thought it would be possible to see the justice.

Williams escorted Mr. Tener over to the Supreme Court chamber, where they were informed it would be impossible to see Justice Moody just then, as the justices were about to return to the bench after their luncheon intermission. So Mr. Tener and his companion stood in the corridor to watch the procession of justices pass between the ropes which guard them from interference by the public as they go from the ante room to the court chamber. [The Court sat in a room in the Capitol until its own building was completed in 1935.128] As Justice Moody went by he caught sight of the famous coach of his old Haverhill team and instantly recognized him, although he had not seen him in years. The justice broke ranks, extended his hand to Mr. Tener, greeted him cordially and exchanged a few words of reminiscences about the old baseball days, while the court was waiting within.129

Tener served less than one term in Congress, resigning on January 16, 1911 to take office as the newly-elected governor of Pennsylvania. Tener was unusual even among prominent baseball-law crossovers, because he managed to keep one foot in each field. For example, while serving in Congress he played in the first-ever Democrats-versus-Republicans congressional baseball game in 1909.130 Then, while serving as governor, Tener accepted the position of commissioner of the National League in 1913, held both offices until the end of this term as governor in 1915, and remained at the head of the National League until 1918.131

Landis requires no elaborate explanation. He served as a judge on the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois from 1905 to 1922, and as the first commissioner of major league baseball from 1921 to 1944.132 Unlike Tener, he did not manage to keep one foot in each field, at least not for long,133 but to say that his dual careers in law and baseball were subjects of enduring public interest would be an understatement.134

Perhaps the most fitting modern equivalents of Tener and Landis are Jim Bunning and George Mitchell.

Like Tener, Bunning was a professional pitcher in his youth and a lawmaker in later years. As a player, he was Tener’s superior. Bunning spent 17 years in the major leagues with the Detroit Tigers (1955-63), Philadelphia Phillies (1964-67 and 1970-71), Pittsburgh Pirates (1968-69), and Los Angeles Dodgers (1969), and was a seven-time All-Star. He was a crossover extraordinaire within baseball, winning more 100 games, recording more than 1,000 strikeouts, and throwing no-hitters (including a perfect game against the New York Mets on June 21, 1964) in both the American and National leagues. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1996.135 Bunning has spent most of his life since leaving baseball as a lawmaker. He served on the city council of Fort Thomas, Kentucky, from 1977 to 1979, in the Kentucky State Senate from 1979 to 1983, and in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1987 to 1999. In 1998, he was elected to the U.S. Senate from Kentucky and he was re-elected in 2004. He has announced that he will not seek another term, which means he will leave office on January 3, 2011.136

Like Tener, Bunning was a professional pitcher in his youth and a lawmaker in later years. As a player, he was Tener’s superior. Bunning spent 17 years in the major leagues with the Detroit Tigers (1955-63), Philadelphia Phillies (1964-67 and 1970-71), Pittsburgh Pirates (1968-69), and Los Angeles Dodgers (1969), and was a seven-time All-Star. He was a crossover extraordinaire within baseball, winning more 100 games, recording more than 1,000 strikeouts, and throwing no-hitters (including a perfect game against the New York Mets on June 21, 1964) in both the American and National leagues. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1996.135 Bunning has spent most of his life since leaving baseball as a lawmaker. He served on the city council of Fort Thomas, Kentucky, from 1977 to 1979, in the Kentucky State Senate from 1979 to 1983, and in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1987 to 1999. In 1998, he was elected to the U.S. Senate from Kentucky and he was re-elected in 2004. He has announced that he will not seek another term, which means he will leave office on January 3, 2011.136

There are striking parallels between Mitchell and Landis’s law-to-baseball crossover careers. Both graduated from prestigious law schools – Landis from Northwestern (it was then called Union Law School), Mitchell from Georgetown – and spent many years in private practice. Both served as federal district judges – Landis in Illinois, Mitchell in Maine in 1979-1980.137 Both were enlisted by major league baseball to cross over during reputational crises in the sport – Landis in response to the corruption highlighted by the Black Sox scandal, Mitchell in response to the steroids scandal.138 Of course, there are significant differences as well. Although Mitchell served briefly as a federal judge, he has spent the bulk of his public-service career as a lawmaker, representing Maine in the U.S. Senate from 1980 to 1995. In addition, like Tener, Mitchell has moved back and forth easily between baseball and the law, including, for example, remaining a member of the law firm of DLA Piper US LLP while preparing the Mitchell Report, and returning to government work from time to time as well.139 And in fairness to Mitchell it must be said that he has a reputation for civility.140

There are signs that this pattern might continue with another generation of bright young stars of both baseball and the law. On the baseball-to-law vector, there is, for example, Mark Mosier, now practicing with the prestigious Covering & Burling firm in Washington, DC, who spent three years playing in the San Francisco Giants organization before graduating with honors from the University of Chicago Law School and clerking in 2005 and 2006 for Chief Justice Roberts and his predecessor, William H. Rehnquist.141 And in the law-to-baseball direction, there is, for example, Michael Weiner, Harvard Law School class of 1988, former clerk to U.S. Dstrict Judge H. Lee Sarokin, and heir-apparent to Major League Baseball Players Association executive director Donald Fehr.142

Best-sellers

The tendency of many legal writers to occasionally incorporate baseball into their work requires no additional proofs: judges do it, scholars do it, presidents and legislators do it.143 There is something of a reciprocal tendency among baseball writers.

Take, for instance, Baseball Joe at Yale (1913), of the popular “Baseball Joe” series of sports novels for young people by the pseudonymous Lester Chadwick. John Matson, Baseball Joe’s father, has kind words for lawyers (and others), and even recognizes the possibility and possible value of crossovers. Here is the scene in the kitchen of the Matson family home, as Mr. and Mrs. Matson contemplate Baseball Joe’s impending departure to attend college at Yale:

“I do wish he would get that idea of being a professional baseball player out of his mind,” went on Mrs. Matson, and her tone was a trifle worried. “It is no career to choose for a young man.”

“No, I suppose not,” said her husband slowly. “And yet there are many good men in professional baseball – some rich ones too, I guess,” he added with a shrewd laugh.

“As if money counted, John!”

“Well, it does in a way. We are all working for it, one way or another, and if a man can earn it throwing a ball to another man, I don’t see why that isn’t as decent and honorable as digging sewers, making machinery, preaching, doctoring, being a lawyer or a banker. It all helps to make the world go round.”

“Oh, John! I believe you’re as bad as Joe!”

“No, Ellen. Though I do like a good game of baseball. I don’t think it’s the only thing there is, however, as Joe seems to, of late. I don’t altogether uphold him in his wish to be a professional, but, at the same time, there’s nothing like getting into the niche in life that you’re just fitted for.

“There are too many square pegs in round holes now. Many a poor preacher would be a first-class farmer, and lots of struggling lawyers or doctors would do a sight better in a shop, or, maybe even on the ball field. Those sentiments aren’t at all original with me,” he added modestly; “but they are true just the same. I’d like to see Joe do what he likes best, for then I know he’d do that better than anything else in the world.”

“Oh, John! surely you wouldn’t want to see him a professional ball player?”

“Well, I don’t know. There are lots worse positions in life.”

“But I’m glad he’s going to Yale!” exclaimed Mrs. Matson, as the little family conference came to an end.144

More recently, the authors of some popular and highly-regarded baseball books have shown a marked interest in (and some sophistication about) the law, especially the Supreme Court. Jim Bouton and Bill James, plus Supreme Court Justice Harry A. Blackmun, present an interesting sequence.

First, Bouton: In his August 27-28, 1969, entry in Ball Four: My Lie and Hard Times Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues, Bouton writes, “We lost a 2-1 heartbreaker in extra innings. It was tough to take. On the other hand, President Nixon today nominated Judge Haynsworth for the Supreme Court. I think that will turn out to be a more famous defeat.”145 Bouton was reporting on events that occurred on August 28, when the Houston Astros lost to the St. Louis Cardinals,146 and on August 18, when President Richard Nixon announced the nomination of Judge Clement Haynsworth.147 Bouton was correct. On November 21, 1969, Haynsworth became the first Supreme Court nominee since 1930 to be denied confirmation by the U.S. Senate.148

Second, James: One theme of his The Politics of Glory: How Baseball’s Hall of Fame Really Works is the Hall of Fame candidacy of New York Yankees shortstop Phil Rizzuto. As James explains,

A key argument made by Rizzuto’s supporters, and occasionally by Rizzuto himself, is that shortstop is a defensive position first, and that therefore we should be willing to put shortstops who weren’t outstanding hitters [such as Rizzuto] into the Hall of Fame.

James is skeptical. He concedes that “[t]here is obviously some truth” to the argument that the relative importance of defensive and offensive performance tends to be weighted unusually heavily toward defense for shortstops, but cautions that

[T]here is also a danger here, which is that if it isn’t carefully watched, this develops into the common-to-the-type argument – that it doesn’t matter what a shortstop hits, because many shortstops don’t hit. That argument implies that the Hall of Fame should reflect the shortcomings of players in the same proportion as it does their strengths, which is rather like Senator Roman Hruska’s defense of G. Harold Carswell, a Nixon nominee for the Supreme Court. Hruska supported Carswell because “mediocre people need representation on the Supreme Court, too.” Mediocre ballplayers do not need representation in the Hall of Fame.149

Except for misspelling Carswell’s middle name (it was Harrold150), and slightly misquoting Hruska (who said, “Even if he is mediocre there are a lot of mediocre judges and people and lawyers. They are entitled to a little representation, aren’t they, and a little chance?”151), James’s use of the Carswell/Hruska analogy rings true. By near-consensus among knowledgeable observers in 1970 (when he was nominated to the Supreme Court), and ever since, Carswell was a mediocre lawyer who did not belong there. His nomination was regarded by some as an “act of vengeance” pursued by Nixon in angry response to the senatorial rejection of Judge Haynsworth that Bouton had predicted. The Senate agreed with Bill James about representation of the mediocre: Carswell was also rejected.152 (Rizzuto, however, was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1994.153)

Third, Blackmun: After the failed nominations of Haynsworth and Carswell, Nixon nominated an indisputably qualified and confirmable character, Judge Harry A. Blackmun. Blackmun was promptly and overwhelmingly confirmed, and served on the Supreme Court from 1971 to 1994. He became a something of a baseball literary figure in his own right, with his opinion for the Court in Flood v. Kuhn.154

There are plenty of others. Lawrence Ritter’s The Glory of Their Times, for example, is peppered with references to the law and lawyers – even the Harvard Law School – by the early greats he interviewed.155 The prize for the most colorful law story in baseball literature, however, surely goes to Leo Durocher. It is too long to reprint here, and too convoluted to summarize. Suffice it to say that in the course of the chapter titled “A Hamfat Politican Named Happy” in his book Nice Guys Finish Last, Durocher claims that Supreme Court Justice Frank Murphy objected to Durocher’s 1947 suspension from major league baseball on the ground that it violated several provisions of the Bill of Rights.156

Judicial Appointments

Baseball and the language of the game are not uncommon in the work-product of judges, legislators, presidents, and bureaucrats,157 but they rarely show up in the business of making judges – the announcements, hearings, and debates that make up the judicial appointment process. Rarely, but not never. Which suggests, perhaps, that baseball has at least a small part to play in every aspect of the law.

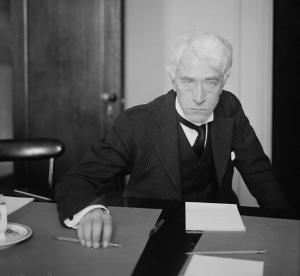

Theodore Roosevelt was president of the United States from 1901 to 1909, and during those years he had the opportunity to fill three openings on the Supreme Court. He made his first and most famous appointment, Oliver Wendell Holmes, in 1902. Holmes was a great disappointment to Roosevelt, primarily because once he was on the Court, Holmes failed to support the Roosevelt administration’s vigorous enforcement of federal antitrust laws, especially in the famous Northern Securities case in 1904.158 Roosevelt is often quoted as saying of Holmes, “I could carve out of a banana a Judge with more backbone than that!”159 In 1903, Roosevelt used a second opening on the Court to appoint William R. Day, a longtime friend and supporter of William McKinley, the president whose assassination had opened the presidency to Roosevelt. Day was on the side of Roosevelt’s angels in the Northern Securities case. He soon frustrated Roosevelt, however, by failing to support all of Roosevelt’s assertions of executive power and progressive social legislation.160 Roosevelt expressed his frustration with Holmes and Day when announcing his third Supreme Court appointment (William Moody) in 1906: “I have been to bat three times on the Supreme Court justiceship business, and have struck out twice.”161 This might have been not only a slap at his first two appointments, but also a salute of sorts to Moody’s longstanding interest and involvement in baseball.162 Ironically, Moody would serve only briefly on the Court (until 1910), while Roosevelt’s two strike-outs would serve until 1922 (Day) and 1932 (Holmes).163

A century later, it was the nominee who turned to baseball in the judicial appointment process. In 2005, Judge John G. Roberts, Jr. was nominated by President George W. Bush to be Chief Justice of the United States. In his testimony during a confirmation hearing before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Roberts said:

While many advocates on the left and right would like a Court that promotes their agenda, I do not want that and neither do the American people. What we must have, what our legal system demands, is a fair and unbiased umpire, one who calls the game according to the existing rules and does so competently and honestly every day. This is the American ideal of law. Ideals are important because they form the goals to which we all strive. We must never abandon our ideal of unbiased judges, judges who rule fairly without regard to politics.164

Roberts’s invocation of the umpire excited several of the Senators considering his nomination, and drew the attention of the news media as well. Senators and commentators hostile to Roberts treated his comment as an equation165 (judging is just like umpiring), while those whose sympathies were with him treated it as an analogy166 (there are similarities between the role of judge and the role of umpire).167 That kind of treatment has become part of the package for an individual nominated for an important job in the federal government in the late 20th or early 21st century,168 just as it used to be part of the package for an individual umpiring a baseball game in the late 19th or early 20th century.169

Maybe there really is no end to the connections between baseball and the law, or the lessons of each for the other.

*****

But it is important to keep things in perspective. The fact that baseball and the law are close should not overshadow the fact that generally speaking the most important events in baseball are the ones that occur on the field, not in court, and most important events in the law have had little or nothing to do with baseball. Thus, for example, the race barrier in major league baseball was first broken when Jackie Robinson played the game, not when he first entered a first major-league contract with Branch Rickey and the Dodgers.170 And Robinson did it without help from the courts. He played in his first major league game on April 15, 1947, seven years and one month before the Supreme Court declared racially segregated schools unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education.171

And yet when Brown was decided in 1954, the Court did not turn to the precedent of Jackie Robinson and the Dodgers; rather, it focused on its own earlier decisions.172 Likewise, Curt Flood’s career as a player did not end in 1972, when the Supreme Court upheld the power of his employer to enforce the reserve clause in his employment contract against him.173 It ended in 1971, with the Washington Senators, because (depending on how you look at it) either he played poorly or he did not want to play.174 And this summer Sonia Sotomayor was appointed to the Supreme Court neither especially because of nor especially despite her opinions in such cases as Major League Baseball Properties, Inc. v. Salvino, Inc.175 and Silverman v. Major League Baseball Player Relations Committee, Inc.176

It is also suggestive that in chronologies in leading baseball reference books, important “baseball-and-the-law” events tend to show up in the years when they manifested themselves on the field, rather than in the courtroom. Thus, for example, in Thorn, Birnbaum, and Deane’s Total Baseball, the Federal Baseball case appears in 1915 (when the Federal League stopped playing games), rather than 1922 (when the case was decided); the Black Sox scandal shows up in 1919 (when the games were played, and allegedly thrown) rather than the early 1920s (when legal proceedings were underway); and the Flood v. Kuhn case is reported in 1970 (when Curt Flood sat out the season in protest against his trade by the Cardinals to the Phillies), rather than in 1972 (when the case was decided).177 Conversely, in the index to volume 259 of the United States Reports (the official reports of the decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States), the Court’s decision in the Federal Baseball case is listed under “Anti-trust Acts” and “Interstate Commerce,” not “Baseball,” and in volume 407, the Court’s decision in Flood v. Kuhn is listed under “Antitrust Acts,” not “Baseball.”178

Baseball and the law: forever together, but not one and the same.179

ROSS E. DAVIES is professor of law at George Mason University and editor of “The Green Bag: An Entertaining Journal of Law.”

Notes

1 See generally, e.g., Spencer Weber Waller, Neil B. Cohen, and Paul Finkelman, eds., Baseball and the American Legal Mind (Garland 1995); Roger I. Abrams, Legal Bases: Baseball and the Law (Temple Univ. Press 1998); Brad Snyder, A Well-Paid Slave: Curt Flood’s Fight for Free Agency in Professional Sports (Viking 2006); see also Amy Beckham Osborne, Baseball and the Law: A Selected Annotated Bibliography, 1990-2004, 97 Law Library J. 335 (2005).

2 And leader of several law schools over the years, serving as dean of the Rutgers School of Law–Newark, Nova University Shepard Broad Law Center, and Northeastern University School of Law. He is now the Richardson Professor of Law at Northeastern. See https://www.northeastern.edu/law/academics/faculty/directory/abrams.html (vis. Oct. 10, 2009).

3 Abrams, Legal Bases at 4.

4 Restatement of the Law Second, Contracts § 1 (American Law Institute 1981).

5 See, e.g., ESPN, Inc. v. Office of the Commissioner of Baseball, 76 F. Supp. 2d 383 (S.D.N.Y. 1999); Silverman v. Major League Baseball Player Relations Committee, Inc., 67 F.3d 1054 (2d Cir. 1995); Metropolitan Exhibition Co. v. Ewing, 42 F. 198 (C.C.N.Y. 1890).

6 See, e.g., J. Caldarera & Co. v. Louisiana Stadium & Exposition District, 750 So.2d 284 (La. App. 1999); Scheibeck v. Van Derbeck, 80 N.W. 880 (Mich. 1899); Philadelphia Ball Club v. City of Philadelphia, 44 A. 265 (Pa. 1899).

7 See, e.g., Norwell v. Cincinnati, 729 N.E.2d 1223 (Ohio Ct. App. 1999); Two Are Taken Into Custody for Offering Pasteboards at Excessive Prices, N.Y. Times, Apr. 19, 1923, at 15; Town of Winnfield v. Grigsby, 53 So. 53 (La. 1910).

8 See, e.g., In re Anaheim Angels Baseball Club, Inc., 993 S.W.2d 875 (Tex. App. 1999); Columbus Base Ball Club v. Reiley, 11 Ohio Dec. Reprint 272 (Ohio Ct. Common Pleas 1891).

9 See, e.g., Curt Flood Act of 1998, Pub.L. 105-297, Oct. 27, 1998, 112 Stat. 2824; One of Three Bills Introduced Would Increase Tax on Baseball, Wash. Post, Aug. 6, 1909, at 4; see also, e.g., Daylight Saving Measure May Aid Baseball Clubs, Wash. Post, Jan. 18, 1918, at 8; Baseball Ties Up Lawmaking: Senators Nearly All Fans; Representatives Like Game, Chi. Daily Trib., Apr. 25, 1910, at 1.

10 See, e.g., Nev. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 244A.830 (2009); Sunday Baseball Killed: Indianapolis Legislature Defeats Second Attempt to Pass Law Permitting National Game on Sabbath, Chi. Daily Trib., Feb. 17, 1903; Georgia’s Tax on Baseball, N.Y. Times, Oct. 10, 1885, at 3.

11 See, e.g., Aubrey v. City of Cincinnati, 815 F. Supp. 1100 (S.D. Ohio 1993); Owens v. Town of Atkins, 259 S.W. 396 (Ark. 1924); New Orleans Baseball & Amusement Co. v. City of New Orleans, 42 So. 784 (La. 1907); City of La Crosse v. Cameron, 80 F. 264 (7th Cir. 1897).

12 See, e.g., Statement on the Baseball Strike, Public Papers of the Presidents, 31 Weekly Comp. Pres. Doc. 124, Jan. 26, 1995; Affects 2,400 in Draft: Work or Fight Order Starts Hunt for Jobs by District Men, Wash. Post, July 2, 1918, at 2 (“Wilson to Classify Ballplayers”); see also, e.g., President Helps Baseball Fund, N.Y. Times, May 23, 1917, at 10; His Message Ready: Wilson Gives Most Attention to Tariff Revision, Wash. Post, Mar. 28, 1913, at 5; Hiding from the Crowd, N.Y. Times, Apr. 16, 1889, at 1; Baseball Indorsed: President Cleveland an Admirer of the Manly Sport, Atlanta Const., Apr. 3, 1885, at 5.

13 See, e.g., Governor Involved in Sox Talks, S.F. Chron., May 3, 1988, at D1; Bad News for the Giants, N.Y. Times, Apr. 24, 1889, at 3; Gov. Hill As An Athlete, N.Y. Times, Oct. 20, 1888, at 3; see also, e.g., Office of the Governor of Arizona, Executive Order No. 2005-07 (June 3, 2005) (establishing Arizona Baseball and Softball Commission).

14 See, e.g., Pittsburgh Baseball, Inc. v. Stadium Authority of the City of Pittsburgh, 630 A.2d 505 (Pa. Commw. Ct. 1993); Moore v. Reed, 559 A.2d 602 (Pa. Commw. Ct. 1989); Scott v. Smith, 28 S.E. 64 (N.C. 1897).

15 See, e.g., Bill James, The Politics of Glory: How Baseball’s Hall of Fame Really Works 297 (Macmillan 1994); Baseball Tax Settled, N.Y. Times, Jan. 22, 1918, at 13; Baseball Income Taxable, N.Y. Times, Sept. 6, 1919, at 10; In re Lyman, 40 A.D. 46 (N.Y. App. Div. 1899); Frederick W. Thayer, Improvement in Masks, U.S. Patent No. US 200358 (Feb. 12, 1878).

16 Search for “baseball” in Westlaw’s allcases database of judicial opinions (Oct. 9, 2009); see also Chart 1 and Table 1 above.

17 Popov v. Hayashi, 2002 WL 31833731 (Cal. Super. Ct. 2002); see also Mike Jensen, Throwing it back: Howard homer returned, Phila. Enquirer, Oct. 8, 2009, at E4.

18 C.B.C. Distribution and Marketing, Inc. v. Major League Baseball Advanced Media, L.P., 505 F.3d 818, 824 (8th Cir. 2007), cert. denied, Major League Baseball Advanced Media v. C.B.C. Distribution and Marketing, Inc., 128 S. Ct. 2872 (2008).

19 See, e.g., Rose v. Giamatti, 721 F. Supp. 924 (S.D. Ohio 1989); Rose v. Giamatti, 1989 WL 111447 (Ohio Ct. Common Pleas 1989).

20 Cf. Basic Agreement Between the 30 Major League Clubs and the MLBPA, art. XI (Dec. 20, 2006), http://mlb.mlb.com/pa/info/cba.jsp (vis. Oct. 10, 2009).

21 Flood v. Kuhn, 407 U.S. 258 (1972).

22 Major League Baseball Players Association and the Twenty-Six Major League Baseball Clubs, Grievance No. 88-1 (July 18, 1990) (Nicolau, Chairman); Major League Baseball Players Association and the 26 Major League Clubs, Grievance No. 87-3 (Aug. 31, 1988) (Nicolau, Chairman); Major League Baseball Players Association and the Twenty-Six Major League Baseball Clubs, Panel Decision No. 76, Grievance No. 86-2 (Sept. 21, 1987) (Roberts, Chairman).

23 See, e.g., S. 1114, the Clean Sports Act of 2005, and S. 1334, the Professional Sports Integrity and Accountability Act, Hearing before the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, Sept. 28, 2005, S. Hrg. 109-525 (2006).

24 See, e.g., House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, Weighing the Committee Record: A Balanced Review of the Evidence Regarding Performance Enhancing Drugs in Baseball (Mar. 25, 2008).

25 U.S. v. Comprehensive Drug Testing, Inc., 579 F.3d 989 (9th Cir. 2009) (en banc).

26 United States v. Bonds, 580 F. Supp. 2d 925 (N.D. Cal. 2008).

27 Rosenfeld v. Hudson Valley Stadium Corp., 885 N.Y.S.2d 338 (N.Y. App. Div. 2009); see also, e.g., Elie v. City of New York, 24 Misc. 3d 1243(A), 2009 WL 2767116 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 2009) (Table); Pakett v. The Phillies, L.P., 871 A.2d 304 (Pa. Commonw. Ct. 2005) (judgment against spectator temporarily blinded by foul ball affirmed).

28 See Reply Brief of Appellants, Braman v. Miami-Dade County, Florida, No. 3D08-3245, District Court of Appeal of Florida, Third District, 2009 WL 2898769 (July 24, 2009) (Appeal from a Final Order from the Circuit Court of the Eleventh Judicial Circuit in and for Miami-Dade County, Florida); Appellants’ Initial Brief, Solares v. City of Miami, No. 3D09-1760, District Court of Appeal of Florida, Third District, 2009 WL 2898734 (June 7, 2009) (Appeal of Non-Final Order Denying a Temporary Injunction from the Circuit Court of the Eleventh Judicial Circuit, in and for Miami-Dade County, Florida); see also Michael Vasquez, Miami Commission OKs tweaks in Marlins stadium financing, Miami Herald, June 18, 2009.

29 Monument Realty LLC v. Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority, 540 F.Supp.2d 66 (D.D.C. 2008).

30 In re Havens Steel Co., 2007 WL 2998432 (Bankr. W.D. Mo. 2007).

31 See, e.g., State v. Curley, 2009 WL 1819516 (Ariz. Ct. App. 2009) (“The indictment alleged that Appellant had killed the victim by assaulting him with a baseball bat.”); United States v. Davis, ___ F. Supp. 2d ___, 2009 WL 2950229 (D. Md. 2009) (“there was a ‘hit’ between the DNA found on the baseball cap recovered at the scene and the DNA of the Defendant”).

32 Major League Baseball Players Association v. Garvey, 532 U.S. 504 (2001).

33 United States v. Cleveland Indians Baseball Co., 532 U.S. 200 (2001).

34 Coast Guard, DHS, Safety Zone; Allegheny River Mile Marker 0.4 to Mile Marker 0.6, Pittsburgh, PA, 74 Fed. Reg. 20586-01 (May 5, 2009).

35 Steele v. Turner Broadcasting System, Inc., ___ F. Supp. 2d ___, 2009 WL 2570662 (D. Mass. 2009).

36 Jacob Maxwell, Inc. v. Veeck, 110 F.3d 749 (11th Cir. 1997); see also www.miraclebaseball.com (vis. Oct. 10, 2009).

37 Although reasonable minds can differ on their utility. Compare, e.g., Commonwealth v. Green, 907 N.E.2d 266 (Table), 2009 WL 1586211 (Mass. App. Ct. 2009), with Chad M. Oldfather, The Hidden Ball: A Substantive Critique of Baseball Metaphors in Judicial Opinions, 27 Conn. L. Rev. 17 (1994); see also Mark A. Graber, Law and Sports Officiating: A Misunderstood and Justly Neglected Relationship, 16 Const. Commentary 293 (1999).

38 Ricci v. DeStefano, 129 S. Ct. 2658, 2704 n.12 (2009) (Ginsburg, J., dissenting).

39 Township of Tinicum v. U.S. Department of Transportation, ___ F.3d ___, 2009 WL 2914488 (3rd Cir. 2009).

40 Hendricks v. Geithner, 568 F.3d 1008 (DC. Cir. 2009).

41 Insurance Co. of the State of Pennsylvania v. Pan American Energy LLC, 2003 WL 1432419 (Del. Ch. 2003).

42 Abrams, Legal Bases at 4.