The Starring Tours of 1875: The “Amateurs” Tours, Tournaments and Regional Rivalries

This article was written by Paul Browne

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Big Apple (New York, 2017)

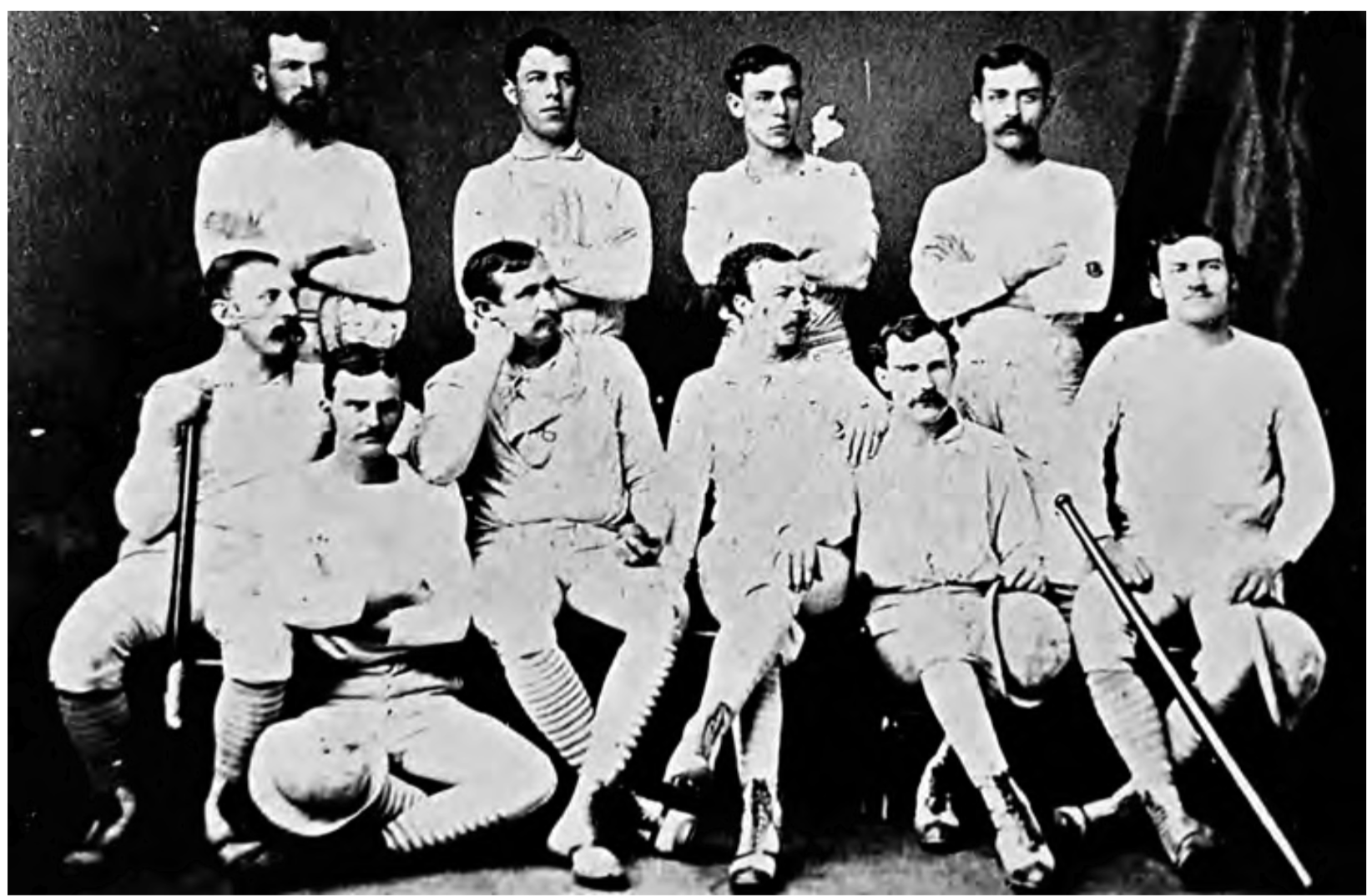

The 1860 Excelsior Club. Star pitcher James Creighton is third from left. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

The Excelsior club of Brooklyn toured Upstate New York, Pennsylvania, and Maryland in 1860, only two years after the formation of the National Association of Base Ball Players. The Nationals of Washington carried the baseball gospel to the Midwest in 1867, shortly after the Civil War. And, of course, the Cincinnati club under Harry Wright accelerated the acceptance of professional clubs with their 1869 and 1870 tours.

Tours by ostensibly amateur clubs from the New York City area began to increase after the Excelsior’s 1860 trip. These journeys, sometimes called starring tours — an example of the interaction between baseball clubs and theater troupes — were an outgrowth of playing on enclosed grounds where the owners of the fields charged admission to spectators, soon sharing part of those receipts with the clubs. Another movement in this trend was baseball clubs playing in trophy and prize games and tournaments. Creeping professionalism was an almost natural outgrowth of these developments.

By 1875, New York City teams were visiting those they identified as “country clubs” fairly routinely. Their more rural rivals were also on the rails visiting each other and their big city opponents. The Mutuals of Meadville in western Pennsylvania started out on a tour through Pennsylvania. Their journey eventually took them to Syracuse, Bridgeport, Connecticut, and New York City. Tours through Upstate New York became so common that the Comets of Norwich, New York, issued an invitation to all clubs touring Central New York to contact them about setting up games. This announcement was published in the New York Clipper on July 31, 1875. That paper’s same issue carried a request from the Mutual Club of Washington, DC, for dates with clubs that had enclosed grounds during their tour of western New York in August 1875. This Mutual club was a black team and the notice was signed by their secretary, Charles R. Douglass, son of Frederick Douglass. Even the New Haven professional team, a member of the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, played some of the same Northeast Pennsylvania teams that the amateurs played. New Haven’s 7–40 record against NA teams may explain why they were looking for competition at this level and why they only lasted one year in the NA.

The Arlington and Flyaway were two New York City teams that were representative of the class of teams that participated in the tours, tournaments, and regional rivalries which defined New York area baseball below the National Association level at this time. An exploration of the clubs’ 1875 seasons will shine some light on the world of these lesser known “missing links” between the early amateurs and the major league, minor league, and semi-pro teams which were coming into existence at this stage in baseball’s development.

When the professional clubs broke off in 1871 to form their own association, some of the remaining teams formed the National Association of Amateur Base Ball Players at the suggestion of Henry Chadwick, and led by the Knickerbocker and Excelsior clubs.[fn]New York Clipper, March 18, 1876.[/fn] The group held no meeting in 1872 but was reorganized in 1873, meeting annually in convention for the next several years and maintaining active committees to deal with issues during the playing seasons. The Arlington and Flyaway were members of this organization, C.W. Blodget of the Arlington serving as Secretary going into the 1875 season.

The Amateur Convention on March 10, 1875, established the rules for the coming season and dealt with the two main issues troubling the amateur community at that time: payment of expenses and “revolving” (players switching teams). The convention determined that amateur clubs could split gate receipts to cover traveling expenses. Clubs that did that frequently played on enclosed grounds, while those that didn’t — like the Knickerbockers — usually played on open grounds that charged no admission to spectators. In order to address revolving, the Association prohibited players who played on one club during a season from playing on another club during the same season.[fn]Sunday Mercury, March 14, 1875.[/fn] In response to a May letter from the Chatham club complaining about Morris Moore’s defection from their club to the Flyaway, the editor of the New York Clipper pointed out that since amateurs could not accept payment, and a contract could not be legally binding without compensation, the revolving rule could not be enforced.[fn]New York Clipper, May 29, 1875.[/fn] The Sunday Mercury and the Clipper would complain about the leading amateur teams in the Association breaking the latter rule and bending the former during the season.

The 1875 tour of the Mutuals of Meadville took them from Pennsylvania eventually through Syracuse, New York; Bridgeport, Connecticut; and New York City. (CRAWFORD COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

A review of the Arlington and Flyaway seasons published in the Sunday Mercury in December 1875 shows the Flyaway starting first with games against their second nines on April 22 and 26, with their first game in competition with other amateur clubs coming against the Cataract on May 1. The Arlington would jump into the fray with a game against the Star of New York on May 20. The Flyaway would play the Keystone, another premier amateur club in the New York City region, on May 24, beating them, 9–7. The Arlington would face the same opponent on June 10, “Chicagoing” the Keystone, 11–0. The Flyaway’s first defeat would come on May 12, losing to the Rose Hill, a team from St. John’s College, 11–7. The Arlington would not report a loss until they left the New York City area for their July Tour of Pennsylvania and Upstate New York. The Irving of Honesdale beat the New York City visitors, 8–6 on July 21. The New York Clipper, however, published two box scores on May 29, 1875. One showed the Rose Hill win over the Flyaway and the other showed the Arlington losing to the college club, 14–6.

The Flyaway were the much more active club, playing 45 games. They won 31 games, lost 11, and had three draws. In contrast, the Arlington played only 21 games, winning 16, losing four, and having one forfeit by the Olympic.

The two clubs met on June 24 on the Union Grounds in Brooklyn. Tied 4–4 after nine innings, the Arlington scored three runs in the top of the tenth and then shut the Flyaway out in their half of the inning. As was the custom of the time, Blodget(t) pitched all ten innings for the Arlington and Fallon for the Flyaway. All runs were recorded as unearned except for one by the Flyaway. No real details of which players did what were listed in the game accounts, including how the Arlington scored their three runs in the tenth.

Tournaments were a regular part of amateur clubs’ seasons. The Flyaway participated in the Watertown, New York, Tournament that started on June 29. First-class clubs paid a $5 entry fee to compete for prizes of $450, $350, and $250. On their way to the tournament, the Flyaway would cross the border to face the St. Lawrence club of Kingston, Ontario, on July 1, beating the Canadian club, 9–2. The Flyaway would play their first game of the tournament on July 2 against the Syracuse Stars, who had lost the opening game of the tournament the day before to the Lynn, Massachusetts, Live Oaks, 13–7. They dropped the July 2 game to the Flyaway, 14–12. The Flyaway’s next game in the tournament would be a 7–1 loss to the Maple Leaf of Guelph, Ontario. Their last game would be a return match with the St. Lawrence on July 6, the Flyaway beating them, 12–2 and taking the $250 third prize. The Live Oaks took first and the Maple Leaf second.

The Flyaway provided the Clipper with a report of their opinion of the Watertown Tournament. While very complimentary towards the organizers, the City, and their host — Mr. Harris of the Kirby House — they could not resist the nearly traditional dig against one of their opponents, the Maple Leafs. They accused the team they lost to of playing a professional, a man named Kerl.[fn]New York Clipper, July 17, 1875.[/fn] No player named Kerl is listed by Baseball-Reference.com, Total Baseball, or David Nemec’s 19th Century Encyclopedia, so, if he was a professional, he was probably not of the highest caliber. In their adventures away from the Metropolis, it was not uncommon for these teams to find some excuse for a loss to any of the “country clubs.”

The Arlington’s western tour, consisting of games in Pennsylvania and Upstate New York, was announced in the Mercury on July 18. It started with the aforementioned loss to the Irving of Honesdale on July 21. The next day they lost to the Carbondale club, 4–3. It was reported that several thousand watched the game. Gillespie and Kennedy are credited among those making “beautiful plays” in the game for Carbondale.[fn]New York Clipper, July 31, 1875.[/fn] Gillespie would go on to an eight-year National League career with Troy and the New York Giants. Kennedy would play four years in the American Association with the Metropolitans and Brooklyn.

The Arlington would recover their form once they hit Scranton, beating three teams in that city. The Scranton club fell, 7–5, in ten innings on July 22, the Hyde Park club being destroyed, 41–4, the day after, and Providence being wiped out, 28–7, the following. Wilkes-Barre would fare better on July 26 but succumb to the Arlington, 15–11. The New York City team returned to New York State on July 27, losing to Binghamton, 9–2. They would complete their tour with a 6–2 victory over the Star of Syracuse on July 28. Baseball in the hinterlands had improved by 1875. Three of the Arlington’s four losses in 1875 occurred on this tour.

C.W. Blodget would provide the Clipper with a report of the tour, published on August 7. He expressed his club’s thanks to the Honesdale, Scranton, and Syracuse people and congratulated Honesdale as the only team to win their game fairly. He criticized the Carbondale and Binghamton teams that had beaten them — as well as Wilkes-Barre whom they had beaten — for playing revolvers and picked nines. Wilkes-Barre’s response was published in the Clipper of September 4. They denied they were a picked nine and stated that every player in the club was a member and resident of the city and that all but one player had been with the club the past two years. They also said that none of their players were paid.

Carbondale was a slightly more complicated matter. Early reports of the Arlington’s planned tour indicate that they were to play a team called the Alerts in Carbondale. By the time they reached that city, however, the Alerts no longer existed. They had merged with another Carbondale team called the Lackawanna to form the Blue Stockings. This team existed before the Arlington tour and lasted into 1876. If this was a “picked nine,” it is hard to imagine that a city of 6,393 in the 1870 census could have gained an unfair advantage against a New York City team drawing from an 1870 population of 942,292.

The Arlington’s first baseman, Isherwood, seemed to have taken no offense to the Carbondales’ behavior, joining them as their captain on the tour they launched on September 10. He also played first base for Carbondale, as he did with the Arlington, in at least four games. No games as a club are listed for the Arlington after August 17.

The Flyaway decided to skip the Lynn tournament and instead take a tour through New York State themselves. They began what turned out to be a very successful trip on August 23. They won all their games but for one loss and two draws. The loss was to the Syracuse Stars on August 30 by a score of 3–1. They had beaten the Stars in the Watertown tournament and would win again on September 3, 7–4. The Flyaway’s victories were over the Lone Star of Catskill, Murphy of Troy, Clipper of Ilion (twice), Uticas, Franklin of Auburn, Comet of Norwich and Active. They played to a draw twice, 2–2 with the Binghamton Cricket on September 1, the game being called after ten innings, and 7–7 with Sunnyvale on September 4. It was reported that the first game against Ilion was played in Johnstown, New York, with the Flyaway getting $300 for their 20–8 win.[fn]New York Clipper, September 4, 1875.[/fn]

The $300 prize at Johnstown again raised the question of amateur status. This was a hotly debated subject during the 1875 season. The Sunday Mercury, in its preseason article for 1875, had raised the issue, stating in reference to amateur clubs, “It is questionable whether there are a hundred in the entire country.”[fn]Sunday Mercury, March 28, 1875.[/fn]

In its summary article at the end of the season, the Brooklyn Eagle stated, “It should be borne in mind, however, that in most cases of this kind the amateur nines were not exactly amateurs in the strict sense of the word, for two-thirds of the so-called amateur nines of 1875 included players who were compensated for their services, if not by regular salaries — as in the professional organizations — at least by a share of gate receipts, or some other form of remuneration. Hence such nines were able to devote the more time to that practice and training necessary to place them in a position to cope more successfully with the regular professional teams, than regular amateur nines could.”[fn]Brooklyn Eagle, November 23, 1875. (Thanks to Richard Hershberger for providing this reference.)[/fn]

While the article did not include the Arlington or Flyaway in their enumerated list of semi-professional teams, they ended that list with “and in fact every prominent amateur club of the country.” The Flyaway were certainly among the prominent amateur clubs as the Eagle listed them as the leading such team in New York City for 1875. The Arlington placed several players on the New York City all-star team that played a series of games with the best Brooklyn players at the end of the 1875 season, so they would also most likely have been considered among the prominent clubs. It was stated later in the article, “Two tours of a genuine amateur character only are known in the history of the game, and they were the tour of the old Excelsior club in 1860 …; and the grand Western tour of the National Club of Washington in 1867.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

The division between professional and amateur clubs was not resolved with the 1871 formation of the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players. The status of those clubs which were not fully salaried stock clubs had varied before the divide and continued to evolve in the seasons leading up to 1875 and for years to come after. Before the launch of the 1876 season, the arrival of the National League would complicate matters for those clubs not included in the new organization even further. A review of the tours and tournaments of 1875 exemplifies the status of a confusing class of clubs on the verge of the next major change in the baseball world.

PAUL BROWNE is the author of “The Coal Barons Played Cuban Giants: A History of Early Professional Baseball in Pennsylvania, 1886–1896” (McFarland). His article on the Cuban Giants’ first victory over a major league team appears in SABR’s “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the Nineteenth Century.” Browne has been a member of SABR since the mid-1990s. He has contributed several player biographies to the SABR BioProject, a previous article in the 2013 “National Pastime,” McFarland’s journal “Black Ball,” SABR’s Nineteenth Century and Minor Leagues committees, as well as local newspapers. Browne is executive director of the Carbondale Technology Transfer Center.

Sources

Articles

Brooklyn Eagle, 1875.

Carbondale Advance, 1875.

New York Clipper, 1874–76.

New York Sunday Mercury, 1874–76.

New York Times, 1875.

Books

Nemec, David. The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball. New York, N.Y.: Donald I. Fine Books, 1997.

Seymour, Harold. Baseball: The Early Years. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1960

Thorn, John, Palmer, Peter & Greshman, Michael, Editors. Total Baseball, Seventh Edition. Kingston, New York: Total Sports Publishing, 2001.

Websites

http://www.baseball_reference.com