The Third Time Is the Charm: The 1939 Pensacola Fliers

This article was written by Sam Zygner

This article was published in Fall 2024 Baseball Research Journal

The white sand beaches and warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico provide a pleasant distraction to the residents and tourists of Pensacola. A sense of optimism swept the Pensacola community in 1939 as the economy took a turn for the better with the ending of the Great Depression. During that summer, another form of amusement provided a diversion to local baseball fans: a case of baseball pennant fever. For the Fliers of the Class B Southeastern League (SEL), it proved to be their most memorable season.

The SEL included teams in Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, and Georgia. During Pensacola’s initial years in the circuit, from 1927 to 1930, the club experienced mixed success. The debut season resulted in a respectable record and fourth-place finish in the eight-team league. In 1928, the Fliers (92–54) edged out the Montgomery Lions (91–57) for first place before falling to the Lions in the league championship series, four games to two. However, the Fliers’ fortunes crashed in the next two years, landing them in the basement both times before the league folded because of financial reasons.1

Pensacola entered the fray again in 1937 in the newly established six-team SEL, led by manager Frank “Pop” Kitchens. The Fliers (83–52) quickly made their mark, finishing five games ahead of the Selma Cloverleafs (78–57), only to lose to the Mobile Shippers in the finals, four games to three.2 In 1938, ownership of the team transferred to John “Wally” Dashiell, who named himself manager.3 Dashiell was no stranger to the minor leagues, having toiled in the bush leagues for 15 seasons, including two in Pensacola in 1927 and 1928. In addition, his résumé included one year of piloting the Class C Jacksonville Jax (1934) and three with the Class C Tyler Trojans (1935–37). Dashiell, a sure-handed second baseman, also appeared in one game with the Chicago White Sox in 1924.4

Dashiell was a part owner of local radio station WCOA, which broadcast Fliers games, and he possessed a keen business sense.5 Through clever marketing, the club drew just under 72,000 fans to the corner of G Street and Gregory Street in 1938.6,7 Among the most popular promotions at Legion Field included Ladies Day (18 games for $3 total) and outlandish events like donkey baseball. Low-priced tickets were available at the famous Pilot Club or Red’s News Stand for Tuesday and Friday home games.8

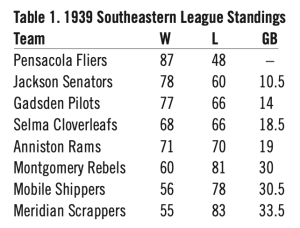

Dashiell’s leadership experience and discerning eye for evaluating talent proved vital in ensuring a second consecutive first-place finish. The Fliers (95–53), now an affiliate of the Brooklyn Dodgers, easily outdistanced the second-place Selma Cloverleafs by 10½ games. Disappointingly, Pensacola fell to the Mobile Shippers, four games to two, in the first round of the playoffs.9

Prospects for 1939 seemed bright. Returning regulars from the 1938 team included first baseman Charley Baron (.280, 69 RBIs), shortstop Bobby Bragan (.298, 69 RBIs), utilityman Rudy Laskowski (.315, 7 HRs, 60 RBIs), second sacker Norris “Gabby” Simms (.322, 86 runs), and outfielder Neal Stepp (.330, 69 RBIs). Furthermore, Kinner Graf (16–13, 3.21 ERA) and Johnny “Big Train” Hutchings (18–6, 2.25) brought experience to the pitching staff.10 Despite the change of major-league affiliation from the Dodgers to the Philadelphia Phillies, many of the core players remained.

The air was electric with anticipation on Opening Day. Known as “The City of Five Flags,” Pensacola, with a population of approximately 37,000, still had a small-town feel.11 Most people did not lock their doors at night and citizens cared for their neighbors during rough times. The local Jaycees of the Chamber of Commerce announced plans for Opening Day ceremonies. The festivities started with a parade through the streets of downtown to Legion Field. It was led by five local girls, who were followed by vehicles carrying players from the Fliers and their nemeses from the previous two years, the Mobile Shippers. Honors for throwing out the first pitches fell to Pensacola Mayor L.C. Hagler and Mobile Mayor Charles A. Baumhauer.12

An estimated crowd of over 6,000 crammed the stands. Southpaw Zack “Dutch” Schuessler, a veteran of four minor-league campaigns, toed the slab for the Fliers. He was coming off his best season, having won 20 games for the Class C Helena (Arkansas) Seaporters of the Cotton State League.13 Tensions ran high between the teams, with several arguments breaking out during the contest. The Fliers built an early 4–1 lead, with the Shippers cutting the lead to 4–3 in the eighth inning. Schuessler worked out of several jams before the eventual deciding run came in the bottom of the eighth, when Laskowski grounded into an apparent double play, but a bad throw to second allowed Alex Pitko to score. Mobile scored in the ninth but fell short, 5–4.14 The Shippers would not be a factor for the pennant in 1939. The Fliers and Jackson Senators established themselves as the class of the league, battling for the top spot in the first half of the season. The Sens featured six regulars with batting averages of .294 or better. They savaged SEL pitching, scoring 826 runs to lead the league. Their most proficient batter was minor-league legend Prince Oana, who finished the season slamming 39 home runs and driving in 127; both numbers led the SEL.15

On the other hand, Pensacola won with the best pitching in the league and solid fielding. The Fliers’ roster was full of talented players. Four regulars— Bobby Bragan, Leslie “Bubber” Floyd, Alex Pitko, and Harry Walker—and pitchers Hutchings and Garth Mann went on to major-league careers.

Scouts considered right-hander Hutchings the most likely to make the majors. At 6-foot-2 and just over 250 pounds, the Big Train’s most effective tool was his devastating fastball, which he combined with better-than-average control. As evidence, he finished the season averaging fewer than three walks per nine innings, and his 205 strikeouts led the league.16 During July’s SEL All-Star break, Hutchings represented minor-league stars from around the country and appeared in baseball’s centennial game in Cooperstown, New York, pitting the Cartwrights against the Doubledays. Hutchings performed well for the Doubledays, working three scoreless innings while striking out six in a 9–6 victory.17

Pensacola and Jackson jockeyed for the top spot until the end of June. The Fliers separated themselves from June 21 through July 1, winning 11 of 12 games. They did not relinquish the league lead.

With two weeks left in the season, Dashiell sent Warren “Red” Bridgens to the mound against the fourth-place Cloverleafs on a typical humid evening in Selma, Alabama. A Jackson loss to Gadsden and a Fliers victory would clinch the pennant. Bridgens was not up to the task, giving up five runs in the third inning, and gave way to Hutchings to finish the game. Pensacola plated a couple of runs in the seventh inning to take a 7–6 lead. Pensacola secured the win in the ninth when Bragan hit a grand slam, ensuring the 11–6 victory. The news soon arrived that Gadsden had upended Jackson, 9–2, and the celebration was on. It was an incredibly satisfying night for the Big Train, who earned his 22nd win of the season.18

The four-team playoffs used an arrangement called the Shaughnessy format, which pits the top seed against the fourth seed while the second and third seeds play each other, the higher seed getting the home-field advantage. It was devised for the International League in 1933 by Frank Shaughnessy, the general manager of the Montreal Royals. It was quickly adopted by other leagues and is commonly used in many sports today. The strategy was successful in boosting attendance and maintaining fan interest late in the season.19

The SEL postseason began with pennant-winning Pensacola facing fourth-place Selma and second-place Jackson opposing third-place Gadsden. The Fliers quickly dispatched the Cloverleafs, sweeping them in four games. Schuessler earned a pair of wins, and Hutchings and Graf hurled shutouts to collect the other victories. That set up the much-anticipated championship, with Jackson (who took their series, 4–1) hoping to play the spoiler.20

The Fliers received a scare in the opener at Legion Field, taking a beating by Jackson, 8–4. The visitors pounded out 14 hits against Graf and Hutchings.21 The Fliers bounced back the next night, winning 7–2. Schuessler scattered eight Senators hits and Stepp accounted for three hits and four RBIs to lead Pensacola before the series switched to Jackson for three games.22 The Senators shut out the Fliers, 6–0, in the third game but dropped the next three contests, all in extra innings, by scores of 5–4, 8–7, and 3–2.23 Schuessler brought the pennant home in style, earning the win in front of nearly 5,000 fans at Legion Field. “Dutch” held Jackson to six hits and struck out Prince Oana three times. A Simms bunt in the bottom of the ninth resulted in the winning run. After two years of frustration, the victory earned the Fliers their first Southeastern League title.24 Pandemonium was the day’s word as locals partied the night away.

By winning the SEL championship, Pensacola earned the right to play the Augusta Tigers, the South Atlantic League champions (83–56), in the Little Dixie Series, for bragging rights as the top Class B team in the Southeast. The New York Yankees affiliate featured six players who would go on to major-league careers, most famously Billy Johnson, who played the hot corner for the Yankees in 1943 and the postwar years before finishing up with the St. Louis Cardinals.25

The best-of-seven series kicked off in Pensacola in front of 5,000 fans. Hutchings started Game One. The Fliers staked themselves to a five-run lead in the first inning. The Tigers offense responded and tied the game in the seventh, 5–5. Dashiell pulled his starter in the eighth inning, but Mann extinguished the fire. The Fliers stayed in the game thanks to some dazzling plays by shortstop Bubber Floyd. Charley Baron scored on a walk-off base on balls in the 10th frame, securing a 6–5 Fliers victory.26 The Tigers took the next two games, 5–2 and 15–7. Hutchings turned the tide, winning Game Four, 4–2. Graf and Schuessler closed the books on Augusta by winning the final pair, 3–2 and 3–0. It was a perfect end to a magical season, proving the adage that the third time is the charm.

The Fliers had the best pitching staff in the league, led by Hutchings (22–10, 1.97 ERA that led the league), Graf (20–6, 2.65), and Schuessler (20–7, 2.29 ERA). They allowed only 3.35 runs per game.27 The Gadsden Pilots, their closest competitor, allowed 4.61 runs per game. Although Pensacola ranked fifth in the league in runs scored (651 runs, 4.72 per game), several of their players had productive seasons. Harry Walker (.322) led the team in batting average, followed closely by outfielder Neal Stepp (.316), first baseman Charley Baron and catcher-infielder Rudy Laskowski (both .315), and second baseman Simms (.309), while shortstop-turned-third baseman Bobby Bragan batted .311 and led the team in homers with 12 and RBIs with 95.28

The Fliers’ regular-season MVP was Hutchings, hands-down, but the postseason honors belonged to Schuessler. The crafty 27-year-old lefty from LaFayette, Alabama, dominated the competition, collecting five wins in the postseason, including a shutout in the finale against Augusta.29 Dashiell returned for one more season in 1940 and nearly brought home a fourth straight flag. In a taut pennant race, Jackson (89–58) edged out Pensacola (89–60) by one game. The Fliers beat Mobile in the first round of the playoffs, four games to three, but Jackson won the championship series over Pensacola in five games.30

“Pop” Kitchens replaced Dashiell in 1941 and finished in fourth place with a 75–67 record. The Fliers were swept in the first round of the playoffs by Mobile. Buster Chatham took over the managerial reins in 1942 and the club finished out of contention before the Southeastern League suspended operations due to World War II.31

After the war, Pensacola returned to the reestablished SEL in 1946 and turned in five winning seasons, winning championships in 1949 and 1950, before the league folded. Today, the Pensacola Blue Wahoos are the Double A affiliate of the Miami Marlins in the Southern League. They play home games at Blue Wahoos Stadium at 351 West Cedar Street.32 The British play-wright and actress Shelagh Delaney said it best, and it applies to championships: “You can remember the second and the third and the fourth time, but there’s no time like the first. It’s always there.”33

POSTSCRIPT

Charley Baron’s real last name was Baronovic, which he changed when becoming a professional baseball player. Writer Phillip Tutor described Baron as playing the game with a brash determination bordering on intimidation. He enjoyed 20 seasons in the minors, from 1931–51, playing in 15 different cities. He served five of those years as a player-manager. The tempestuous batsman rose as high as Triple A in 1946 and 1947 with Rochester of the International League. He had several years in the minors batting over .300 but with little power.34 After retiring, he worked in maintenance for the St. Louis Public School System. He died on May 1, 1997.35

Bobby Bragan was the epitome of a baseball lifer. He made it to the big leagues in 1940 and played three seasons with the Phillies and four with the Dodgers, batting .240 for his career. Bragan, an Alabaman, became infamous for being one of a group of Dodgers who opposed Jackie Robinson being on the team. His attitude later changed, and he developed a friendship with Robinson. After his playing career ended, Bobby had a great deal of success as a manager in the minor and major leagues, including seven years skippering the Pittsburgh Pirates (1956–57), Cleveland Indians (1958), and Milwaukee-Atlanta Braves (1963–66). He also served as the president of the Texas League for seven years, worked in public relations with the Texas Rangers, and served as an assistant to Commissioner Bowie Kuhn. He died on January 21, 2010, at the age of 92.36

Leslie “Bubber” Floyd, known later as “Bubba,” reached the major leagues in 1944 with the Detroit Tigers. He appeared in three games, slapping four hits in nine at-bats before his demotion to Buffalo of the International League. After hanging up his spikes, he worked in transportation sales for a car loading company. Floyd lived to be 83, passing away in Dallas on December 15, 2000.37

After two dominating seasons in Pensacola, Johnny “Big Train” Hutchings made it to the majors the next season with the Cincinnati Reds. The husky right-hander did well, appearing in 19 games, posting two wins and a 3.50 ERA. He also appeared in the 1940 World Series, giving up one run in one inning of work. His World Series share was a welcome gift, and he earned a championship ring when the Reds defeated the Tigers in seven games. In 1940, Hutchings appeared in 19 games with the Reds and eight more in 1941 before he was traded to the Boston Braves for Lloyd “Little Poison” Waner in June, where he spent four-plus seasons until 1946.38 He received a modicum of fame when he gave up Mel Ott’s 500th home run on August 1, 1945.39 Hutchings ended his playing career in 1951 with the exception of two games for the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association in 1959. He later managed the Clinton Pirates of the Class D Midwest League (1959) and Indianapolis of the American Association (1960). The “Big Train” died on April 27, 1963, at the age of 47.40

Rudy Laskowski was a minor-league nomad. His career stretched from 1932 to 1966. He was first signed by the Class A Knoxville Smokies of the Southern Association. As a player, he clocked in for 17 seasons, reaching as high as Double A in 1934 with Milwaukee, 1935 with Toledo and Louisville, and 1946 with Little Rock of the American Association. He proved a valuable asset, playing at every position except outfielder.41 In the middle of his career, he missed five seasons serving his country as a TEC 5 in the U.S. Army. He also managed for 11 seasons in eight different cities, including West Palm Beach for three years, Keokuk, Iowa, for two, and Oklahoma City for two. He was not one to rest: He also ran a successful bowling alley in Chicago in 1950.42 Rudy passed away on June 9, 1993, and was laid to rest in the Florida National Cemetery, Bushnell, Florida.43

Garth “Red” Mann played a significant role in the success of the 1940 Pensacola Fliers, winning 20 games. The slender 6-foot Texan pitched professionally for 12 years, rising as high as the Pacific Coast League (1945–47). His best season came in 1942 with Montgomery of the Southeastern League, when he won 18 games and posted a 2.06 ERA.44 The 1950 Census showed Red working as an assistant warehouseman for an oil company. He died on September 11, 1980, in Waxahachie, Texas.45

Zack “Dutch” Schuessler’s career looked promising following the championship season. His promotion to Birmingham of the Southern Association brought him closer to his big-league dreams. However, he found facing a higher level of hitters more difficult and struggled to win nine and lose 14 games with a suspect 4.94 ERA. Dutch pitched 10 minor-league seasons, compiling a 93–89 record before hanging up his wool togs.46 He later became a teacher in West Palm Beach, Florida. He passed away on August 2, 1959.47

Norris “Gabby” Simms derived his nickname from being precisely the opposite, a man of few words. The quiet Oklahoman began his baseball career as a bat-boy for the Oklahoma City Indians. He broke into organized ball with Opelousas of the Class D Evangeline League in 1936. After the 1939 season, Simms moved on to better opportunities financially, working for 65 years for the Oklahoma National Stockyards with the livestock commission. He passed away on May 9, 2007.48

Neal Stepp spent three seasons with the Fliers as the starting second baseman (1938–40). In 1941, he enlisted in the Army and served in the 77th Second Field Artillery Battery Battalion. He decided not to return to baseball and worked in a supervisory position with Hickory Industries. He died in Hickory, Georgia, the same town where he was born, on June 26, 2004.49

Harry “the Hat” Walker, like Bragan, became a baseball lifer. By 1941, he reached the major leagues with the Cardinals. Walker spent most of his career with the Redbirds and later the Phillies, Chicago Cubs, and Reds. In 1947, he won the National League batting title with a .363 average. In addition, he managed the Cardinals (1955), Pirates (1965–67), and Houston Astros (1968–72). Walker was notorious for bending anyone’s ear who would listen about hitting. He died as the result of a stroke on August 8, 1999, in Birmingham, Alabama.50

When Wally Dashiell decided to retire from baseball, he put down family roots in Pensacola. He co-owned the Martin-Dashiell Insurance Agency, and his wife, Virginia, remained active in several community organizations. His home in the North Hill area of Pensacola is a registered historic site. Dashiell came up to the plate for the last time on May 20, 1972, leaving a legacy the city of Pensacola holds proud. Wally Dashiell, also known as “Mr. Baseball,” continues to be a legendary figure in Pensacola.51

SAM ZYGNER, a SABR member since 1996, is the author of Baseball Under the Palms: History of Miami Minor League Baseball Volume Two: 1962–1991 (Sunbury Press, 2022), Baseball Under the Palms: History of Miami Minor League Baseball The Early Years: 1892–1960, and The Forgotten Marlins: A Tribute to the 1956–1960 Original Miami Marlins (Scarecrow Press, 2013). He received his MBA from Saint Leo University.

NOTES

1 “Southeastern League,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Southeastern_League.

2 “Southeastern League.”

3 Frank Pericola, “Sport Slants,” Pensacola News Journal, January 1, 1938, 2.

4 “Wally Dashiell,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=dashie001joh.

5 Hana Frenette, “If Walls Could Talk—The Wally Dashiell House,” Pensacola Magazine, March 2017, https://www.ballingerpublishing.com/if-walls-could-talk-the-wally-dashiell-house/, accessed August 14, 2024.

6 “1938 Pensacola Pilots,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=05cc7cfa; Matt Colville, “Forgotten Stadiums: Pensacola’s Legion Field,” Stadium Journey, February 27, 2021, https://www.stadiumjourney.com/stadiums/forgotten-stadiums-pensacolas-legion-field, accessed August 14, 2024. Note: Baseball Reference incorrectly refers to the 1927 and the 1937–42 incarnations of the Pensacola team as the Pilots. It also incorrectly refers to the 1928–30 teams as the Flyers, with a y. From 1927 through 1950, every Pensacola team was known as the Fliers.

7 Colville, “Forgotten Stadiums,” Stadium Journey, accessed August 14, 2024.

8 Pensacola News Journal, “Baseball Ladies’ Night Tickets Now On Sale,” April 5, 1939, 5; Pericola, “Local Waste 11 Hits Off Rebel Hurler,” Pensacola News Journal , June 20, 1939, 2.

9 “1938 Southeastern League,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/league.cgi?id=1104948f, accessed August 14, 2024.

10 “1938 Pensacola Pilots,” Baseball Reference. “Gabby,” Shawnee (Oklahoma) News-Star, July 2, 1937. “Big Train,” Pensacola News Journal, September 5, 1939.

11 “Population of Pensacola, FL,”Population.us, https://population.us/fl/pensacola/, accessed August 14, 2024.

12 “Jaycees Finish Plans For First Baseball Game,” Pensacola News Journal, April 18, 1939, 10.

13 “Zack Schuessler,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=schues001lew; Pericola, “6,000 Witness Opening Tilt in Local Park,” Pensacola Journal, April 21, 1939, 10, https://www.newspapers.com/image/352800625/?terms=Pensacola%20Fliers&match=1.

14 Pericola, “6,000 Witness Opening Tilt.”

15 “1939 Southeastern League Batting Leaders,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/leader.cgi?type=bat&id=67f2108a.

16 “Johnny Hutchings,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=hutchi001joh.

17 Pensacola News Journal, “Big Train of Fliers Fans Six Batsmen,” July 10, 1939, 2.

18 Pensacola News Journal, “Jackson’s Loss to Gadsden Ends Chance for Rag,” August 26, 1939, 2.

19 “Shaughnessy Playoffs,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Shaughnessy_Playoffs.

20 “1939 Southeastern League Batting Leaders.”

21 Pericola, “Easy Fly Ball Drops for a Hit to Change Tide,” Pensacola News Journal, September 12, 1939, 7.

22 Pericola, “Aviators Get 12 Wallops off Four Pitchers,” Pensacola News Journal, September 13, 1939, 7.

23 “Southeastern Playoff Even,” Huntsville Times, September 15, 1939, 6; “Defeat Jackson in Fifth Game After 13 Frames,” Pensacola News Journal, September 16, 1939, 2.

24 Pericola, “Takes 12 Frames to Subdue Wild Senators 3 to 2,” Pensacola News Journal , September 17, 1939, Section 2, 16.

25 “1939 Augusta Tigers,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=693e2f3b. Players who reached the major leagues are Charlie Biggs, Mike Garbark, Ford Garrison, Al Gettel, Billy Johnson, and Art Rebel.

26 Pericola, “Jeffcoat Hurls Great Ball as Relief Chunker,” Pensacola News Journal, September 19, 1939, 2.

27 “1939 Southeastern League Batting Leaders;” Frenette, “If Walls Could Talk.”

28 “1939 Southeastern League Batting Leaders.”

29 “Zack Schuessler,” Baseball Reference; Pericola, “6,000 Witness Opening Tilt.”

30 “Southeastern League,” Baseball Reference.

31 “Southeastern League.”

32 “Blue Wahoos Stadium,” MILB.com, https://www.milb.com/pensacola/team/about.

33 Baseball Reference, https://www.azquotes.com/quote/1344332. Retrieved July 4, 2024.

34 Phillip Tutor, “Baron was the Rams’ hittin’ manager,” The Unforgettable & Irrelevant Anniston Rams, https://annistonrams.com/2022/08/09/combustible-baron-managed-and-hit-rams-to-1948-playoffs/, accessed August 14, 2024.

35 “Charley Baron,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=baron-001cha, accessed August 14, 2024.

36 Maurice Bouchard, David Fleitz, “Bobby Bragan,” SABR, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bobby-bragan/, accessed August 14, 2024.

37 “Bubba Floyd,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=floyd-001les, accessed August 14, 2024.

38 “Johnny Hutchings,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=hutchi001joh. Retrieved on December 13, 2023; “Casey Plays Hunch And Nabs Hutchings,” The Sporting News, June 19, 1941, 3.

39 Michael Wilson, “History of the Atlanta Braves,” Braves History Blog, https://braveshistoryblog.wordpress.com/2017/08/22/johnny-hutchings-gives-up-500th-career-home-run-to-mel-ott-august-1-1945/. Retrieved on December 13, 2023.

40 “Johnny Hutchings,” Baseball Reference.

41 “Rudy Laskowski,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=laskow001rud, accessed August 14, 2024.

42 “Rudolph J. Laskowski in the 1950 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/219495357:62308?tid=&pid=&queryId=93a9460f-44c8-49ab-8749-44a58834b3d7&_phsrc=XPL1&_phstart=successSource, accessed August 14, 2024.

43 “Rudy Laskowski.”

44 “Garth Mann,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=mann–001ben, accessed August 14, 2024.

45 “Garth Mann in the 1950 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/187193176:62308, accessed August 14, 2024.

46 “Zack Schuessler,” Baseball Reference.

47 “Zack Schuessler,” Roanoke Leader, August 6, 1959, 6, https://www.newspapers.com/image/554099920/?article=d7436839-6e6a-47a0-aa6c-fcda1b82193d&focus.

48 “Norris Oscar Simms Sr.,” Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/93355198/norris-oscar-simms, accessed August 14, 2024.

49 “Neal Stepp,” Hickory Record, June 29, 2004, 2. See also Ancestry.com.

50 Warren Corbett, “Harry Walker,” SABR, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/harry-walker/, accessed August 14, 2024.

51 Frenette, “If Walls Could Talk.”