The True Greatness of the ManDak League

This article was written by Gary Gillette

This article was published in Our Game, Too: Influential Figures and Milestones in Canadian Baseball (2022)

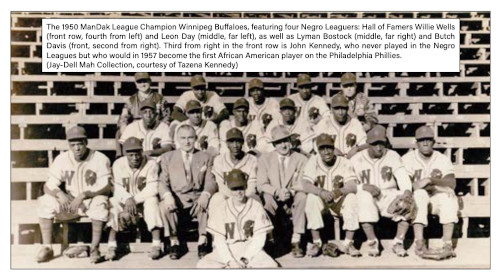

The 1950 ManDak League Champion Winnipeg Buffaloes, featuring four Negro Leaguers: Hall of Famers Willie Wells (front row, fourth from left) and Leon Day (middle, far left), as well as Lyman Bostock (middle, far right) and Butch Davis (front, second from right). Third from right in the front row is John Kennedy, who never played in the Negro Leagues but who would in 1957 become the first African American player on the Philadelphia Phillies. (Jay-Dell Mah Collection, courtesy of Tazena Kennedy)

On the dust jacket of his book Small-Town Heroes, author Hank Davis wrote:

For many baseball fans, a major-league team is a flickering image on a television screen or a story in the newspaper. Real baseball is played in their hometown, in a ballpark that seats 5,000 fans, not 50,000. The players wear uniforms like the ones seen on television, but their names are not household words — unless it happens to be summer and you live in Bluefield, West Virginia; Cedar Rapids, Iowa; or Batavia, New York.1

Davis wrote about his 1993 peregrination in the US and Canadian minor leagues. Substitute Brandon, Manitoba, for Bluefield; Minot, North Dakota, for Cedar Rapids; and Bismarck, North Dakota, for Batavia and it would have been just as meet if written in 1950.

According to the 1953 edition of the National Baseball Congress of America’s Official Basehall Annual, most of its member teams were “town teams” — a recent trend. “Official records show that more than 70 per cent of the clubs in the combined league and tournament program are ‘town’ teams.”2 The teams that made up the Manitoba-Dakota League of the 1950s followed that trend. The big-market Winnipeg clubs of the first four years were owned by businessmen; the rest of the league was made up of quintessential town teams.3

Hundreds of minor-league teams populated the US and Canadian landscapes before 1960 — 446 teams organized into 58 so-called bush leagues in 1950 alone. That is not to mention uncounted numbers of semipro leagues that thrived when baseball was king of the sports world. Yet the modest ManDak League of the Northern Prairies made an impact in its eight years of operation in the 1950s that has outlasted almost all the other leagues of the day.

One subtle tribute to the extent of the Man-Dak’s fame is that most fans — and many writers, too — in the twenty-first century believe that the ManDak was a professional minor league and not “just” semipro. Labeling the ManDak as merely semipro borders on insulting. Before the Organized Baseball apocalypse in the late 1950s and 1960s laid waste to most minor leagues and uncounted semipro leagues, semipro ball was the heart of the game in vast stretches of North America — especially in towns too small to support even low-level minor-league clubs.

Semipro teams — town teams, factory teams, and teams sponsored by local businesses and civic or fraternal organizations — were the pride of many a small town, large manufactory, or city neighborhood. They were a locus of civic pride as well as an important recreational outlet.

THE FOUNDATION

Often called “senior leagues” to distinguish them from amateur youth leagues, semipro baseball leagues had deep roots in prairie towns and cities both north and south of the 49th parallel in the late 1940s. The new ManDak League grew out of those roots in Manitoba and North Dakota, each of which had integrated baseball traditions of their own during the segregated era.

The ManDak was a noble, if short-lived, experiment made possible by the continuance of racial discrimination against Black ballplayers in the United States even after the American and National Leagues had re-integrated in 1947. It was made possible by a surfeit of available African American talent after baseball’s color line was broken because many short-sighted AL and NL owners refused to sign Black players who were supposedly too old or not as good as their favored White players.

Wilmer “Red” Fields was the ace of Homestead’s mound corps in 1948 when the Grays won the last Negro World Series.4 During the 1940s and 1950s Fields played all over Latin America, but he waxed almost poetic in his autobiography about how lovely his time in Canada was in the 1950s:

There was no comparison between the treatment we received in Canada and the treatment we received in Latin America. In Canada, it was like a home away from home. … In Latin American countries, everything was business. … The Canadian people also wanted ballplayers who represented their city and their community off the field as well as on the field. It was a good feeling. The people there accepted my family with so much enthusiasm that our stay there was the finest we ever experienced anywhere but at our home.5

Kyle McNary said succinctly in the audiobook edition of his Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe: 36 Years of Pitching & Catching in the Negro Leagues: “[Negro League] Players went to Canada, where the seasons were short, the pay was good, and minds were liberal.”6

That opinion was echoed in 2001 by African American player Ron Teasley, a 1950 ManDak All-Star7 hailing from racially polarized Detroit, which still maintained a substantially segregated public-school system in the 1950s.8 Barry Swanton, in his excellent and indispensable history The ManDak League: Haven for Former Negro League Ballplayers, 1950-1957, placed Teasley’s opinion atop page 1: “Ron Teasley … stated that in Canada the players were judged by their baseball ability, not by their color.”9

Teasley reaffirmed that sentiment in a 2018 interview, saying, “[African American ballplayers] found it refreshing and enjoyable to experience a lack of prejudice, both on and off the field, because Canadians were so welcoming.”10

For eight memorable summers on the Northern Prairie, the ManDak League punched well above its weight in the 1950s.

HOW GOOD WAS THE MANDAK?

“By most accounts, the quality of play in Canada at this time was roughly equal to the high levels of America’s minor leagues,” wrote Michael Stahl in a 2017 piece entitled “The Secret History of Black Baseball Players in Canada’s Great White North” for Salon.com.11 His opinion concurs with others from the 1950s.

The authoritative publication Dominionball: Baseball Above the 49th reprinted several assessments of the ManDak’s level of play12 from Swanton’s book:

“Equal to Class B ball,” according to Minot manager Lefty Lefebvre in 1950. When Lefebvre made his evaluation, he hadn’t yet seen the Winnipeg Buffaloes, who featured future Hall of Famers Leon Day and Willie Wells, and who would take home the inaugural ManDak championship,

“Between Class A and Class B,” according to Minot manager Otto Huber in 1951.

“Pacific Coast League,” according to Minot pitcher Al Lyons in 1957. A very marginal former big-league pitcher in the 1940s (6.30 ERA in 100 innings) when he was in his prime in his late 20s, Lyons had previously spent seven years in the PCL, mostly as an outfielder. His 3.08 ERA led the ManDak in 1957 when the league was on its deathbed and when Lyons turned 38.

Swanton’s history also included other opinions about the ManDak’s quality:13

“Many knowledgeable people believe the league was somewhere between Double A and Triple A.”

Winnipeg Royals skipper Dee Moore adjudged the ManDak to be “as good as the strongest Class B league in organized ball” in 1953.

Ted Bowles, a scribe who covered the ManDak for the Winnipeg Free Press, thought the league “rated between Class A and Class B ball” before Winnipeg left the ManDak for the Class C Northern League.

Jim Adelson, who did radio play-by-play of Minot Mallards games in 1951 and 1952, put the league at “close to Triple-A.”

Contemporaneous observers are often better judges, so Lefebvre’s, Huber’s, Lyons’, Moore’s, Bowies’, and Adelson’s opinions carry extra weight. That is especially true because most of them appear not to have inflated their assessments to make their teams and their jobs look more important – as Lyons obviously was doing, based on the enormous gap in his own performance between the majors and the ManDak. Adelson’s viewpoint is harder to parse.

The pioneering North Dakota radio-TV sports broadcaster’s high estimation of the league’s quality is the real outlier. A member of the North Dakota Associated Press Sportscasters and Sportswriters Association Hall of Fame, he spent decades in the Flickertail State covering sports after arriving on the scene at 26 in 1951.14 It is possible that the young broadcaster had not seen enough of the major leagues or the high minors to be able to make that judgment; it is also possible that he was consciously or unconsciously trying to pump up local pride, and make North Dakota look better to outsiders.

In any case, as with other opinions about the ManDak that place it at the high minor-league level, the evidence just doesn’t bear that out. Radcliffe biographer McNary stated, “Some compared the [ManDak] league favorably to Double A or Triple A in the minors.” He quotes Winnipeg Elmwood Giants owner Alex Turk’s opinion: “The Northern League wasn’t close. We would have beaten their All-Star team.”15 Given that the 1946-1962 Northern was only a Class-C league, that’s not much to shout about.

Regrettably, evaluating the competitiveness of independent leagues is not straightforward. Independent leagues are defined as not being affiliated with a major-league farm system; they are colloquially called “indy leagues.” Most indy leagues are a mix of former professional players and newbies of unknown quality. In the Internet age, it is possible to find background information and even statistics for amateur players in indy leagues, as almost all of them have college playing experience.

In the mid-twentieth century, though, most players in semipro leagues had no pro experience and fewer had collegiate experience. Most were truly local heroes: former high-school stars who might have attended a tryout camp run by pro scouts for a big-league club. These camps would gather optimistic young athletes who dreamed of playing in “The Show,” but only a tiny percentage would ever sign a professional contract — and those who signed often washed out of pro ball within a year.

The Pirates — who finished last or next to last in the NL in the decade after World War II and were not an organization chockful of talent by any measure — ran just such a three-day tryout camp in Thamesville, Ontario, in August 1947. About 300 hopefuls attended, but only six were reportedly signed by Pittsburgh — very daunting odds.16 That is especially true because the Bucs’ farm system had 19 clubs in 1948, so hundreds of roster slots were available for marginal prospects who probably had no future but who might surprise and pan out.

Of the six who survived the tryout and signed with Pittsburgh, three could be tracked. Two of them appear to have never played in the minor leagues, likely being released by the Pirates before or during spring training in 1948. The third, a high-school pitcher from Windsor named Jim St. Louis, never played in the Pittsburgh farm system but did play four years of Class C or D ball, only one of which was for a big-league farm club.17

A clear-eyed look at the upstart league requires painstaking research into the past and future Organized Baseball and Negro League careers of all ManDak players. Although contemporary observers and some who have studied the league’s history have commented that the ManDak’s quality of play might have been as good as the high minors, rigorous analysis shows that might have been true only of the strongest ManDak teams, but not of the rest of the clubs.

The only realistic yardstick to measure the quality of the ManDak is the established stratification of the minor leagues in the 1950s. In the 1950s, Organized Baseball essentially operated at six levels below the majors, from Class AAA and AA to Classes A, B, C, and D. (For political reasons, from 1952 to 1957, the Pacific Coast League was classified as “Open,” but the PCL was a Triple-A league prior and afterward. The change in nomenclature did not correspond to a meaningful change in quality.)18

CRITICAL RELATIONSHIP TO THE NEGRO LEAGUES

The Negro Leagues, by MLB’s pronouncement of December 2020 now considered “Major Leagues” between 1920 and 1948,19 were on life support in the 1950s. The strongest Major Negro League, the Negro National League, had collapsed after 1948 when many White major-league owners realized that Jackie Robinson’s stellar performance was not a fluke, and they belatedly undertook the scouting and signing of Black ballplayers.

The Negro American League (NAL), founded in 1937, struggled on after its older sibling died in 1948, but it was hemorrhaging talent at an escalating rate each year.20 By the late 1950s, the NAL was essentially a loose, low-level barnstorming confederation that merely traded on the NAL’s name and history as a marketing strategy.

Baseball historian Scott Simkus did a deep dive into the 1951 NAL in his Outsider Baseball Bulletin in 2011 while studying the integration of Organized Baseball five years after Jack Roosevelt Robinson’s debut with Triple-A Montréal in 1946. Simkus examined many different angles and concluded that the NAL was not even as good as the typical 1951 Class-C league. However, as he acknowledged, the still prevalent discrimination against Black ballplayers would have had an unquantifiable negative effect.21

Using Simkus’s data on the percentages of players at each level who would eventually make the major leagues, as well as the percentages of Black players at each level who ultimately reached “The Show,” it seems that the NAL was at least Class B and possibly as good as a Class-A league of the day, yet very far below the big leagues.

The waning fortunes of the sole remaining Negro League surely contributed to the health of the ManDak. If the NAL had been thriving, most of the Negro Leaguers who migrated to the ManDak would probably have stayed home, where they had a better chance of being scouted and signed by a major-league organization.

As the 1950s progressed and more of the 16 AL and NL clubs integrated, hundreds of additional Black players were scooped up to play in their farm systems, starving the NAL of young talent — and, by extension, starving the ManDak of good young Black ballplayers. By the mid-1950s, the NAL was probably no better than a run-of-the-mill Class-C league of the day.

METHODOLOGY

For a presentation at the 2019 Canadian Baseball History Conference, I analyzed all regular players in the ManDak’s history. A “regular batter” was defined as having 100 or more at-bats in a season. (No walk data was available for the ManDak.) A “regular pitcher” was defined as having made 10 starts or having 10 decisions (wins plus losses) in a season. These criteria produced an average of nine batters and three pitchers per team per year – a reasonable number for a league that played no more than 78 games.

Because all pitchers batted, and starters were expected to throw complete games, and because pitchers sometimes played other positions, a few moundsmen also qualified as batters. The result was an average of 11.8 regulars per team. 243 players qualified as regulars in at least one season. They were individually evaluated to estimate their skill level by examining their pre- and post-ManDak careers in professional baseball, along with how old they were when they played in the ManDak.

Note that player ages referenced in this article are Actuarial Seasonal Ages (ASA), a metric devised by Pete Palmer, legendary baseball historian and analyst and co-editor of Total Baseball and The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia. A player’s ASA is simply the current season minus his year of birth; it is one-half year older than the commonly used Seasonal Age.22 (Players whose birth years were unknown were excluded from the calculations.)

ASA adopts the actuarial concept that brackets a person’s calendar age from six months before their birthday to six months afterward. For example, a person who is 29 years and 7 months old would be considered as 30 years old. This eliminates the problem of having someone 29 years and 364 days old being labeled as 29, when they are obviously much closer to 30.

Examining careers before and after their stay in the ManDak and adjusting for their age and their performance, an equivalent level of OB play was assigned to all 243 ManDak regulars: their Organized Baseball Equivalency (OBEq). Players with no professional experience were assigned to Class E, which didn’t exist in the 1950s, but was a designation reserved for semipro leagues in the 1930s and 1940s.23

Taking a clear-eyed look at the pedigree of the ManDak regulars, the idea that the league was the equivalent of a high minor league, or that any of its players could have still played well in the majors, becomes merely a romantic notion. OBEq estimates of the players who started most of the games in the ManDak place the league somewhere between a Class-B and a Class-A league. Allowing for discrimination against Black ballplayers in OB that caused some to be placed below their true level of ability, it seems reasonable to evaluate the ManDak as about as good as a typical Class-A minor league of the day.

The career of ManDak star Clifton “Zoonie” McLean is enlightening. The North Dakotan was a standout collegiate player at Minot State University, one of the ManDak’s biggest stars, the only player to appear in all eight years of the league’s existence,24 and the shortstop on Barry Swanton’s ManDak All-Star Team.25 His career batting average was .322. McLean reportedly declined an offer from the Philadelphia Athletics to turn pro,26 yet Otto Huber evaluated McLean as only a Class-A shortstop in 1951 when he was in his prime at 27 — a year before he won the ManDak batting title by hitting .369.27

Breaking down the ManDak’s quality by OBEq ratings of its regulars, it is easy to see that the league could not have been comparable to the high minor leagues of the 1950s. Placing Class A with the higher leagues helps the comparison, but it still leaves almost half of the ManDak’s regular seasons played by guys who were comparable to Class-B players or worse.

True, some players rated as “Class E” because they had no OB or Negro Leagues experience might have had the potential to play in the minors, but even bumping ManDak star Zoonie McLean up to Class A (per Huber’s scouting report) doesn’t substantially change things — and McLean clearly stood head and shoulders above the crowd of semipro players that filled out league rosters.

| MANDAK OBEq by Regular Seasons | ||

| Zoonie McLean = E | ||

| OBEq | Reg Seasons | Percent |

| AAA | 38 | 16% |

| AA | 45 | 19% |

| A | 45 | 19% |

| B | 47 | 19% |

| C | 33 | 14% |

| D | 7 | 3% |

| E | 28 | 12% |

| Total | 243 | 100% |

| High Minors (AA-AAA) | 34% | |

| Low Minors (A-B-C-D plus E) | 66% | |

| Upper-level (A-AA-AAA) | 53% | |

| Lower-level (B-C-D plus E) | 47% | |

| MANDAK OBEq by Regular Seasons | ||

| Zoonie McLean = A | ||

| OBEq | Reg Seasons | Percent |

| AAA | 38 | 16% |

| AA | 45 | 19% |

| A | 53 | 22% |

| B | 47 | 19% |

| C | 33 | 14% |

| D | 7 | 3% |

| E | 20 | 8% |

| Total | 243 | 100% |

| High Minors (AA-AAA) | 34% | |

| Low Minors (A-B-C-D plus E) | 66% | |

| Upper-level (A-AA-AAA) | 56% | |

| Lower-level (B-C-D plus E) | 44% | |

CONUNDRUM OF THE GREAT NEGRO LEAGUERS

Since 2020, players from the Major Negro Leagues (MNL) are de jure as well as de facto major-league players. However, the ManDak was born two years after the last MNL season in 1948; therefore, unless a Negro Leaguer was still capable of playing a big-league game two years after his last MNL season, he wouldn’t have been at a big-league level in the ManDak in 1950, never mind 1955 or later.

The career of a major-league ballplayer is arduous and short, and two years is ample time for their skills to erode unless they are young and still learning. Even the Hall of Famers — who are preternaturally good at their peaks and, therefore have more room to decline over time while still being above-the-bar big-leaguers — will eventually succumb to the irresistible elements of time and age. Often they keep playing long after merely mortal players have hung up their spikes, but that doesn’t mean they are nearly as good.

Because so much of the ManDak’s fame rests upon the strong shoulders of its cohort of great Black players and other Negro League All-Stars, a closer look is instructive. More than 40 percent of all ManDak regular seasons were logged by former Negro Leaguers.

Wilmer Fields, the well-traveled pitcher and hitter who appeared in the ’48 East-West Game, was five years past his All-Star appearance when at age 31 he hit .356 with four homers in 24 games pitching and playing third base for Brandon in 1953. He was called “one of the best players to ever play in the ManDak League,”28 and played well in Toronto in the Triple-A International League in 1952.

By his own account, Fields received four serious offers from AL or NL clubs to play in their organizations in the late 1940s or early 1950s. Fields said that he turned them all down because he was making as much money or more playing fewer games in the Negro Leagues and Latin America, and because he thought it wouldn’t be a good move for his family.29

While his reasons should be respected, it also means that he did not face the toughest competition in the world in the 1950s after the AL and NL had integrated, so it’s hard to say whether he would have topped out at Triple A or been able to thrive under the bright lights in the majors. Regardless, his performance in his brief sojourn in the ManDak indicates he was starring in an inferior league.

Leon Day, who passed through the Bronze Doors in Cooperstown in 1995, was 34 in his first tour of duty in the ManDak in 1950 and 1951. Day pitched well in 40 innings in Triple A in 1951 but was much closer to mediocre in ’52, two levels below in the Class-A Eastern League. In 1953, before his return to the ManDak at 38, he wasn’t even that effective in a different Class-A league where he was 10 years older than the typical pitcher. At the plate, Day hit .259 with no power in Class AAA and only .279 with little power in Class A. As great as he was in his halcyon days, Day was apparently no longer capable of holding down a regular job in the majors by the 1950s, though he had plenty left in the tank to become a two-way star in the ManDak.

Long-lived Double Duty Radcliffe’s stint in the ManDak basically amounted to a cameo. At age 49 in 1951, the durable catcher and pitcher hit .340 in 15 games while going 2-0 on the mound for Elmwood, including hurling a complete game in which he fanned eight batters.30 Radcliffe also played briefly for Winnipeg in 1952 when he was half a century old! Needless to say, no one could play at that age in the major leagues; Double Duty and his spitter were unapologetically outfoxing players young enough to be his children. Listening to Radcliffe’s recollections via McNary, it is easy to hear that the loquacious former star knew he was a man among boys in the ManDak.31

Universally loved Hall of Famer Ray Dandridge had torn the cover off the ball in his mid-to late 30s in Triple-A Minneapolis. He then destroyed ManDak pitching to the tune of a .360 average with 40 extra-basers in only 328 at-bats with Bismarck in 1955 – the year he turned 42. “Dandy” was tragically deprived of his shot in “The Show,” but that was five to seven years earlier and he was probably no better than a good Triple-A player by ’55.

Hall of Famer Willard Brown was a decade past his Negro League salad days when he joined the ManDak. The fearsome slugger could still rake, as his .302 BA with 57 extra-base hits in 544 at-bats in 1955 showed — but that was when he was playing in Double A. In reality, Brown might have been a good Double-A ballplayer at the end of the line in 1957 — as was the ManDak.

Cooperstown resident Willie “The Devil” Wells played regularly in the ManDak only in its first two seasons. Wells is one of the greatest ballplayers in history — Black or White — as well as one of the least-known of baseball’s true titans. Yet the idea that he could play shortstop in a high-level league in his mid-40s is ludicrous.

His teammate Frazier “Slow” Robinson provided the key: Wells positioned himself very shallow in the infield to cover for his inadequate arm. Facing big-league hitters, though, that adjustment would have been a disaster, because major leaguers hit the ball much harder than bush-leaguers. Groundballs that major-league shortstops playing deeper would gobble up would have rocketed by Wells for base hits, sending Wells to the bench or to retirement.

Robinson talked about how well the elderly Wells played in the ManDak:

[Wells at 46 years old] was an old man up there in Canada, but he could still play shortstop. And he could still hit; he might have hit around .375 up there [actually, .309 but with little power]. He’d play maybe one or two games a week, but that was because he was managing and playing. It’d look like he wasn’t going to throw you out, but he didn’t miss throwing out nobody. He played a shallow shortstop because his arm had lost a little something. Sometimes it’d look like he was standing up there by the pitcher, playing shortstop.32

Big-league veterans can adapt as they age and their physical skills diminish. A hitter who can no longer get around on a good fastball can “cheat” by starting his swing earlier. A pitcher whose fastball is several MPH slower than in his prime can still get hitters out with pinpoint control, plus breaking stuff, or by changing speeds.

There is a downside to those adjustments, though, even when they are successful. Hitters who cheat on fastballs become very vulnerable to breaking balls and changeups because they’ve tailored their stroke to the heat and end up too far in front of other pitches. Pitchers who rely on control, crooked pitches, or junk can become predictable. Even if the hitters don’t figure out what’s coming, these high-mileage arms cannot overpower a hitter when their location is off, their curves flatten out, or they are simply tipping their slow stuff.

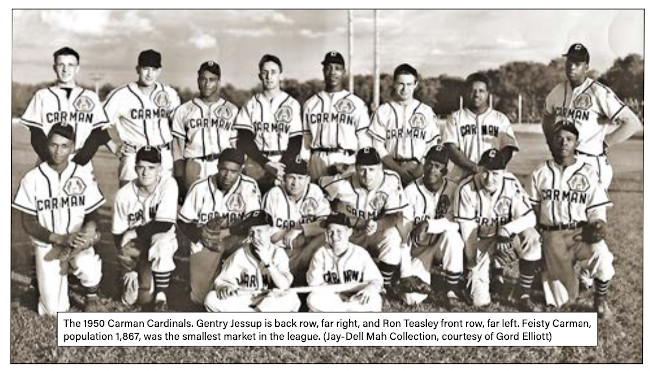

The 1950 Carman Cardinals. Gentry Jessup is back row, far right, and Ron Teasley front row, far left. Feisty Carman, population 1,867, was the smallest market in the league. (Jay-Dell Mah Collection, courtesy of Gord Elliott)

Other ManDak stalwarts, both Black and White, have similarly divergent markers.

Roy Weatherly, who forged a 10-year journeyman’s career in the White major leagues (811 games, 2781 at-bats, .286 BA but only 98 OPS+), won two ManDak batting titles with gaudy averages of .412 and .371, while also topping the loop in homers once. Last seen in the bigs in 1950 mostly as a pinch-hitter, Weatherly was (to echo broadcast legend Red Barber) “tearin’ up the pea patch”33 four to seven years later in the ManDak.

Thirteen-year National League veteran Ken Heintzelman (319 games, 1502 innings, 3.93 ERA) pitched for one season in the ManDak in 1955 at age 40, posting a 4.50 ERA after playing out the string in Triple A for three years.

“With his arm and his bat, [Marion “Sugar”] Cain was one of the most dominant players of the ManDak League from 1951 to 1957″34 when 37-43 years old! Indeed, the popular ManDak star fashioned a 62-31 record on the mound in his seven-year sojourn in the ManDak, while batting .319 and whacking 10 round-trippers with the willow. In the years for which there are complete stats available, Cain led the ManDak in ERA twice, strikeouts three times, complete games once, innings once, wins once, and percentage twice. Nevertheless, Cain’s Major Negro League career played out much differently. He bounced around in the late 1930s, where limited statistics show him posting a 1-4 record and a painful 8.28 ERA. All things considered, Cain probably peaked at a Double-A level professionally.

ManDak superstar Lomax “Butch” Davis had a similar profile. In three years as a regular, Davis led the loop in steals once and won the batting title twice in his mid-30s with averages of .406 and .454, losing a third title on the final day of the season despite his .369 BA!35 His .341 average with 27 long hits in 67 games with the 1947 NNL Baltimore Elite Giants showed his potential, but he was probably a good Triple-A player when he was scorching ManDak pitching.

A five-time East-West Game selection, Gentry Jessup was a star in both the Major Negro Leagues and the ManDak. However, available data shows a losing career record in the NAL, though an ERA somewhat better than average. With Carman from 1950 to 1952, Jessup was “considered a workhorse”36 who led the league in wins once while batting .304. Lefty Lefebvre thought Jessup was the best pitcher in the Man-Dak, but the Minot manager also rated the league as Class B.37

Lots of players are literally major leaguers but not good enough to play regularly in the major leagues. They might ride the pine for a while — perhaps even for years — but they are not really major-league-caliber players. The major leagues are effectively defined by those who play every day (including rotation starters and closers), not by the substitutes who give them a rest, who collect garbage time during blowouts, or whom the manager is forced to play because of injuries.

Too often, people confuse having been a major-league player at one time or another with being good enough to play in the major leagues right now – or, in this case, when they were active in the ManDak. One could become a big-league regular a couple of years in the future, but only be a Class-A ballplayer in the ManDak, as Jerry Adair showed. On the other side of a ballplayer’s typical career arc, one could have been a majorleague star six years ago but would be retired if not facing lower-level opposition such as that in the ManDak. Adair would ultimately play 13 years in the American League, nine with the Orioles. He didn’t become a regular with Baltimore until 1961, four years after he hit .356 with line-drive power in the ManDak while still in college. Given his age and his subsequent OB minor-league record, he was likely a Class-C player in 1957, certainly no better than Class B.

Finally, there is Ian Lowe, “considered by some to be the best third baseman in the Man-Dak League.”38 He hit .319 in 1950 and tied for the league lead in RBIs with 39, while also managing the powerful Brandon Greys to first-place finishes in 1950 and 1951, and to the playoff championship in ’51.39 Lowe’s pro career consisted of 29 games in Class B in 1946, where he hit .223 with zero power. Lowe was later inducted into both the Manitoba Baseball Hall of Fame40 and the Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame:41 He is the prototype of a small-town hero, but he was not more than a Class-C ballplayer.

When players who were reserves in the majors step into another league and succeed as regulars, it is obvious that their new league is of lower quality. When marginal big-leaguers dominate another league, it is clear that such a league is of much lower quality.

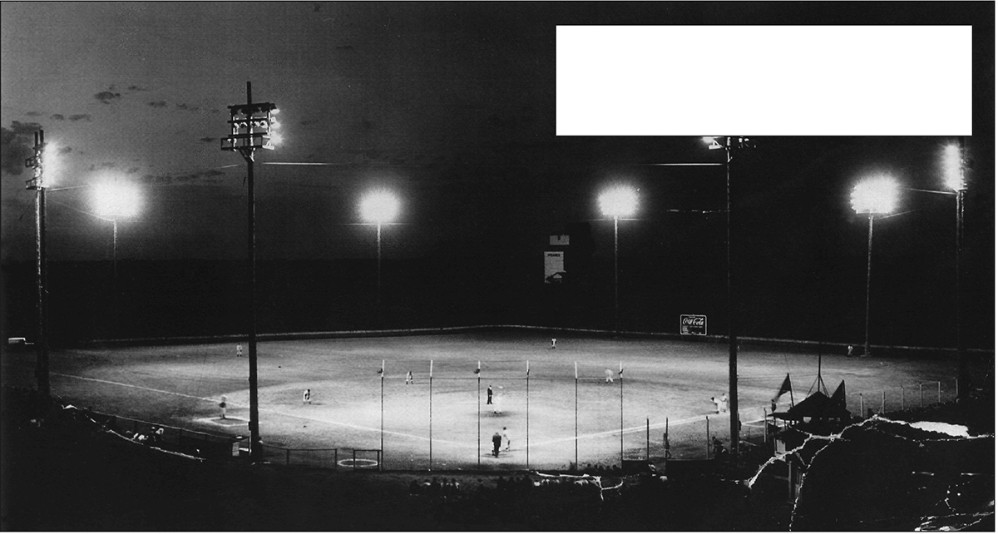

The lights go on in Carman! On July 6, 1950, Carman unveiled its floodlights at the ballpark. Perhaps visiting Brandon found the improved lighting more helpful, as they defeated the Cardinals 12-5. (Jay-Dell Mah Collection, courtesy of Gord Elliott)

THE NUT GRAF

The reason that the level of play in the Negro Leagues of the late 1940s and the 1950s is relevant to the ManDak is that the reputation of the ManDak rests in large part upon its importation of former Negro League players — particularly future Hall of Famers Willie Wells Sr., Ray Dandridge, Willard Brown, and Leon Day. Satchel Paige’s cameo in the ManDak is oft-touted, but the legendary pitcher was hired solely as an attendance-building gimmick and appeared in just two league games, hurling only three innings in each.42

There is no doubt that the careers of this distinguished quartet were at an elite level, even among those memorialized in Cooperstown. A close look, however, tells a somewhat different story. Of the four Hall of Famers, Brown and Dandridge stayed for but a single summer in the ManDak, while Day and Wells lingered on the Northern Prairies for only two years.

More importantly, Brown, Dandridge, and Wells were all 42 years old when they strode onto ManDak diamonds. While younger, Day was no ingénu at 34, and was already a veteran of 10 Major Negro League seasons, as well as having served two years in the US Army in World War II. High-profile Negro League veterans like Double Duty Radcliffe helped burnish the ManDak’s reputation, but they didn’t play regularly, and thus did not contribute much to the league’s level of play.

The rest of the Negro League players who came north were not nearly so accomplished, or else they didn’t tarry long in the league. Of 82 other regular ManDak players with Negro League experience, none had been stars aside from the Hall of Famers and Radcliffe. Another four dozen or so former Negro Leaguers also played in the ManDak, either as reserves or for short stints. Of those, only Chet Brewer and Ted Strong were included in Top 100 Black Baseball Players selected by eminent Negro League historian James Riley for the 2008 edition of the ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia.43

Brewer, Radcliffe, and Strong were also the only ones among the Black Baseball stars nominated for consideration for the Hall of Fame in late 2021 by the 42 for 21 Committee poll of more than 100 prominent Negro Leagues scholars and Black Baseball historians.44 Player-manager Brewer’s time on the mound in the ManDak was very brief, as he appeared in only three games for Carman in 1953. Strong played only 23 games for Minot in 1950.

A telling indicator that the ManDak’s Negro Leagues’ cohort was past its prime is the weighted average age (by season) of former Negro Leaguers when playing regularly in the ManDak: 33.6 years old (ASA). That is long after the mid- to late-20s peak of most big-leaguers, and it was a whopping 5.6 years older than the ages of other ManDak regulars (almost all of whom were White).

REASONS FOR THE COLLAPSE

After World War II, high-school and college baseball was in decline in the United States as football and basketball came to dominate the prep athletic scene. Though there was a huge postwar surge in minor-league teams, leagues, and attendance in the late 1940s, that quickly collapsed as television began its rapid march to ubiquity in American society. Sitting in front of the family TV set displaced many forms of entertainment — including attending ballgames at the local ballyard.

With the populace staying home, the two major leagues of the day created a lucrative new revenue stream by televising their games. In the early years of baseball on TV, clubs limited their telecasts to local markets, partly due to the cost of transmitting signals via expensive landlines, and partly out of deference to minor-league operators.

The lure of extra lucre soon overcame both constraints, with the American and National Leagues televising games nationwide. Many individual AL and NL clubs followed by expanding their reach, realizing that fans in their hinterlands would rather sit in their living rooms on summer evenings, watching baseball for free on TV. On Saturdays, baseball fans could watch major-league teams for free rather than go out to the ballpark and pay to watch bush-league or semipro ballplayers in the flesh.

In his superb history, Swanton identified the primary reasons for the league’s demise as “attendance dwindling and operating costs rising,” along with a belief by “many Manitobans” that “Williston and Bismarck [had] exceeded the salary cap.”45

In 2007 a review in the journal NINE found that Swanton’s “explanation of the ManDak League’s demise [was] abrupt” and didn’t offer much analysis.46 Many leagues before and since have struggled with finding competitive balance between not-so-rich clubs and well-off clubs. In the final years of the ManDak, the better-resourced clubs were located in the oil-rich towns of Williston and Bismarck, North Dakota, but there were multiple other reasons for the ManDak’s expiration.

As for attendance, the overall trend in baseball was so dire that a league like the ManDak could not avoid being fatally afflicted. Almost 33 million fans attended minor-league games in 1950, the year of the ManDak’s birth. By 1957, the year the ManDak died, attendance in the minors had shrunk by 55 percent. Extrapolating those trends to the ManDak’s unique niche, it is not difficult to see why the league was doomed.

Other problems inherent in the ManDak’s founding placed a continuing strain on league operations and club viability. In the first half of the league’s existence, Winnipeg was a member. Its urban area population of 354,069 was more than 10 times the size of the two next-largest markets (Minot at 22,032 and Brandon at 20,598) and almost 200 times the size of Carman’s population of 1,867! Disparities between similarly sized Minot and Bismarck (18,640) and Dickinson (7,469) and Williston (7,378) in the second half of the league’s lifespan were much more manageable, but the damage had already been done by then with the withdrawal of the Manitoban clubs after 1954.

Even before Williston and Bismarck joined the league in 1954 and 1955, respectively, the ManDak regularly suffered from competition issues:

The Minot Mallards completely dominated the league from 1952 through 1954, finishing first in the regular season and in the playoffs each year. In 1952 Minot was the only team in the league with a winning record, going 8-1 in the playoffs to win the championship in very convincing fashion. In 1954 the Mallards finished 10 games ahead of the runner-up in a 70-game season, then went 8-5 in the playoffs to win its third consecutive ManDak crown.

In 1955 Minot finished third, nine games back, during the regular campaign before winning the first round of the playoffs in six games and then sweeping the final series.

In 1956 Williston finished first by two games in a close race, then went 8-5 in the playoffs to capture its first championship over the defending champion Mallards.

The 1957 season almost didn’t happen because finding four viable teams was difficult.47 Bismarck repeated Williston’s feat of finishing first and then winning the championship in a season marked by bad weather and controversy. A protested ruling by the league president resulted in second-place Minot meeting Bismarck in a single-series postseason.

The 1957 championship series gave the struggling league a final big black eye when Minot refused to take the field after Game Three, forfeiting the championship after a dispute about whether the Mallards’ home field remained playable following two days of rain.48

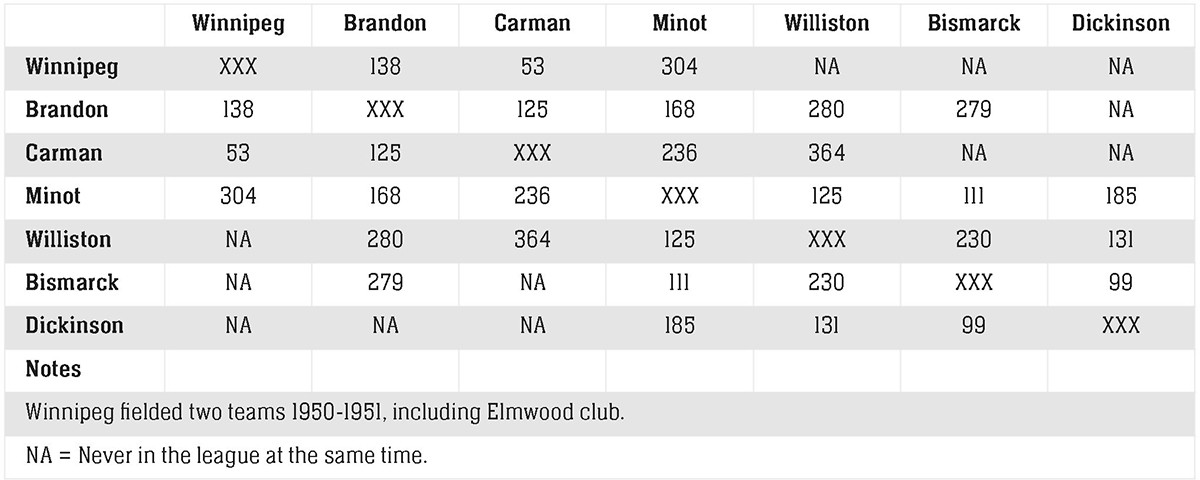

Another vexing issue for the league was long travel distances; the table below that shows the road mileage from Minot to other league member towns. (Minot was the only town to field a team in all eight ManDak seasons.)

MANDAK LEAGUE MILEAGE

Although these long distances were not insurmountable, the extensive travel placed a burden on team finances. It was no coincidence that, as the league struggled with longer schedules after 1952, the average mileage from Minot to the other ManDak cities decreased substantially, from 236 miles (1950-1953) to 125 miles in 1957.

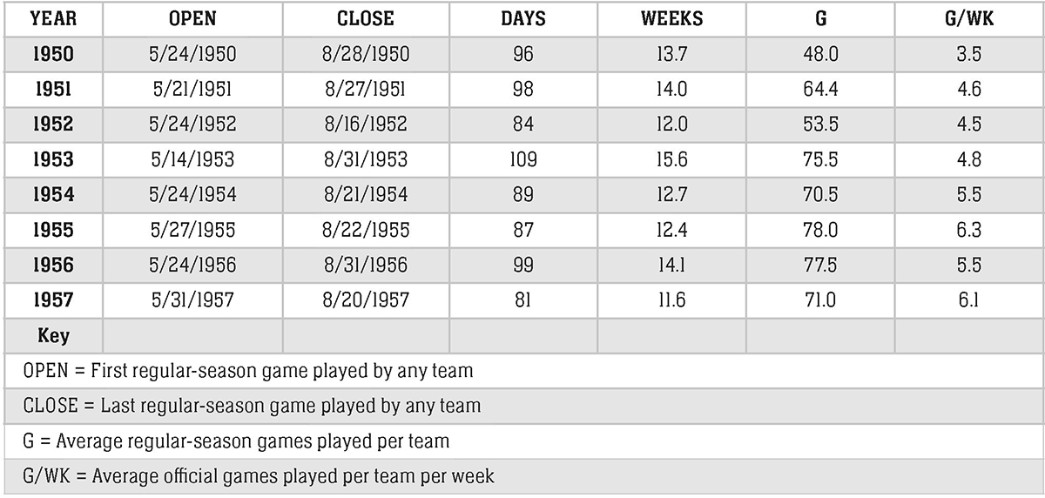

The tables below show how ManDak summers varied in terms of number of league games (not including the playoffs), length of schedule, and the average number of official games played per week. Each year had a new wrinkle. In 1950 no league contests were scheduled on Sundays, but teams played numerous tournament and other exhibition games that didn’t count in the standings. The ManDak’s second summer added league games on the Sabbath, upping the games played by more than a third, yet the teams still engaged in plentiful exhibition and tournament play. Tournament play, including four league-sponsored tournaments, peaked in 1952.

The 1953 and 1956 seasons saw the ManDak clubs play interlocking schedules with other Western Canada semipro circuits, greatly upping travel friction and costs. The number of official games jumped into the 70s in ’53, staying there for the rest of the loop’s life. In a sign of things to come, Winnipeg left the league in ’54 as struggling Brandon and Carman played some “home games” in the provincial capital — though it didn’t forestall their folding for long.

In 1955-1956, the ManDak benefited from fewer Negro League veterans. For those two years, it was really the “NDak League” because all four clubs were located in North Dakota. A shaky Brandon team returned to the league in 1957 or the ManDak wouldn’t have been able to operate. The Greys ended the season unhappily, protesting the ManDak president’s decision to proceed to a shortened playoff schedule without making up all postponed games.

MANDAK SEASONS BY LENGTH AND GAMES

Ultimately, the combined pressure of baseball’s sharply declining popularity, especially below the major-league level, and the mismatch of importing Negro League and high-minors players while operating over long distances in tiny markets made the end of the ManDak inevitable. Those 58 minor leagues and 446 teams who had taken the field across the United States and Canada in 1950 had shrunk to 24 circuits and 173 clubs by 1958.

The history of professional baseball in Manitoba and North Dakota before and after the ManDak era demonstrates that, aside from Winnipeg, the area does not have markets large enough to support any but the most tenuous professional franchises. True, the Manitoba-Dakota League was semipro — not professional — but it ambitiously attempted to operate more like a professional league instead of a local or regional semipro circuit. In essence, the ManDak’s ambitions were also the seeds of its undoing. The league aspired to a higher level of baseball than its constituent members (teams) and their constituencies (the fans) were able to support. In its final summer, ManDak attendance was less than 1,000 per game for all four clubs.

DÉNOUEMENT

After withdrawing from the ManDak at the end of the 1953 season, Winnipeg joined the Class-C Northern League from 1954 through 1964. In 1963-1964, Winnipeg and the league moved up to Class A. In 1969 the capital of Manitoba hosted a short-season Class-A club that drew barely 500 fans per game. All those teams were in the low minors.

From midseason 1970, when Buffalo’s Triple-A team relocated to Winnipeg, through the end of 1971, Winnipeg was an outpost of the Class-AAA International League. In 1971 the Whips were next to last in the IL in attendance, sealing their fate. After they folded, Manitoba would be bereft of professional baseball until the revolutionary new independent Northern League arrived in the mid-1990s.

From 1994 to 2010, the Winnipeg Goldeyes played indy ball in the Northern League, switching to its indy successor, the American Association, in 2011. The Goldeyes are still on the field, though their attendance was only a bit above 1,000 per game in 2021. Pre-pandemic, Winnipeg’s attendance had ranged from 3,900 to 5,700 in their Association tenure.

Before the ManDak, Brandon had not hosted a minor-league team for a full season since 1911, and it would not have another until it consummated a three-year fling with the shaky independent Prairie League, beginning in 1995.

Tiny but proud Carman, naturally, never came close to hosting a professional franchise before or after the ManDak.

South of the border, ManDak heavyweight Minot entered the Class-C Northern League in 1958 with a completely new roster as a Cleveland Indians farm club. The revamped Mallards were far from dominant in the pros, playing .500-.550 ball and struggling at the gate for three seasons. In 1962 a new Mallards team took the field for one final summer, finishing last in the loop. Minot also joined the short-lived Prairie League in 1995. That indy league’s demise after 1997 brought an end to Minot’s professional baseball ventures.

Bismarck also played four years in the old, affiliated Northern League, though the North Dakota state capital waited until 1962 to join the loop. Prior to its ManDak involvement, Bismarck hadn’t hosted a pro team since 1923. Its final gasp in pro ball was in the 1995-1996 Prairie League.

Two decades later, in 2017, Bismarck joined the growing trend of former minor-league towns hosting collegiate summer league teams. It has been a member of the Northwoods League since then. Stronger than all other summer collegiate leagues except for the famed Cape Cod League, the Northwoods operates much like a lower-level pro league — except for not paying its players, who thus retain their amateur eligibility.

In 2018 Minot and Dickinson joined the summer collegiate Expedition League, with Brandon following suit a year later. The Expedition is much more fragile and low-budget — and thus more typical — of these summer leagues than is the Northwoods. Average attendance at its games was 459 in 2021 and 611 in 2019,49 a far cry from the crowds of thousands who lustily cheered the ManDak’s heyday.

Dickinson and Williston hosted a minor-league team neither before the ManDak, nor after.

THE LEGACY

The ManDak was truly a rara avis, loved by its players and its fans. It is remembered today as a treasure that melded community pride with competitive spirit and good, old-fashioned hardball. Nevertheless, community spirit and love for one’s team only goes so far, as former Brooklyn Dodgers fans sorrowfully attest.

The ManDak’s place in baseball history – particularly in Canada – is secure. SABR’s 2005 history of baseball in Canada featured a statue-like pose of Frazier “Slow” Robinson in his Winnipeg Buffaloes uniform front and center on its cover, superimposed over a red maple leaf and a background map of Canada.50

Because of painstaking efforts by such skilled and devoted researchers as Barry Swanton, Jay-Dell Mah, and Gary Fink, the league’s legend has grown in the twenty-first century. Major League Baseball’s better-late-than-never recognition of the 1920-1948 Negro Leagues as full-fledged major leagues has also given an indirect boost to the little league that could.

For a few brief sunlit summers on the Northern Prairie, the Manitoba-Dakota League was not good – it was great. Analysis of the quality of its play does not detract in the slightest from its greatness, which was founded on its enlightened integration of Black players -both on and off the field – and on its rootedness in the community.

With an affectionate nod to English literary “hall of fame” poet Robert Browning, some minor tinkering with two lines from his poem “Andrea del Sarto” nicely sums up the ManDak:

Ah, but a league’s reach should exceed its grasp, Or what’s a (baseball) heaven for?

Historian and consultant GARY GILLETTE is a nationally known baseball author and the foremost expert on Hall of Famer Turkey Stearnes, the Detroit Stars, and the history of the Negro Leagues in Detroit. As founder and chair of the nonprofit Friends of Historic Hamtramck Stadium, Gillette has led the campaign to restore the historic site. His research was key to the approval of a State of Michigan Historic Marker for Hamtramck Stadium and was the basis for two African American Civil Rights Grants from the National Park Service. In 2021 he was the recipient of the prestigious Tweed Webb Lifetime Achievement Award from SABR’s Negro Leagues Committee.

Sources and acknowledgments

It would be a Herculean task to write accurately about the Manitoba-Dakota League were it not for the painstaking, pioneering, and perspicacious work of Barry Swanton, Jay-Dell Mah, and Gary Fink.

Swanton’s ManDak League: Haven for Former Negro League Ballplayers, 1950-1957 is the irreplaceable guidebook, with its detailed descriptions of each ManDak season, standings, playoffs, and assorted other notable events. Black Baseball Players in Canada: A Biographical Dictionary, 1881-1960, which he co-authored with Mah, supplements it beautifully.

Mah’s fabulous AtthePlate.com website provides an online encyclopedia of the history of Western Canada baseball with digital reams of information: in particular, detailed game reports and many valuable and precious images. If other states or regions in the United States and Canada had such a website devoted to their nonprofessional baseball history, the game would be much more popular.

Fink’s deep dive into the statistics of the ManDak bring the descriptions of the league and its players into sharper focus, as well as making analysis so much easier and better.

Kudos and copious thanks to all three of them. RIP Barry Swanton, who passed at age 83 on October 1, 2021.

James A. Riley’s Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues remains a landmark in the field and informs so much of the context and judgments about the players and the era. It is literally indispensable. The Biographical Encyclopedia is a massive volume (more than 900 pages), and I am fortunate to be in the process of editing the second-edition manuscript, which should be published online later in 2022.

Seamheads.com‘s authoritative Negro Leagues Database, carefully curated and maintained by Gary Ashwill and Kevin Johnson, provides the best (by far) statistics for Negro League players through 1948. Baseball-Reference.com was used for AL and NL statistics, as well as minor-league statistics. Note that reliable statistics for the Negro American League after 1948 and for other Negro minor leagues are very hard to find.

Historical information on the minor leagues through 2006 was found in the third and final edition of Baseball America’s Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball. Additional information about the state of the minor leagues after World War II was found in minor-league expert Bob Hoie’s article in John Thorn’s, Pete Palmer’s, and Michael Gershman’s Total Baseball: The Official Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball, seventh edition (2001). More recent information on the minor leagues and on collegiate summer leagues was found on Baseball-Reference.com.

The expanded 2020 edition of Larry Lester’s magisterial book, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1962, was used to verify references to Negro League players’ All-Star appearances.

Population data came from Statistics Canada’s 1951 Census of Population and from the US 1950 Census via their official websites.

Geographical information, including driving distances, was found on RandMcNally.com.

Notes

1 Hank Davis, Small Town Heroes: Images of Minor League Baseball (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1997).

2 Official Baseball Annual 1953 (Wichita, Kansas: National Baseball Congress of America), 30.

3 Barry Swanton, The ManDak League: Haven for Former Negro League Ballplayers, 1950-1957 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2006), 7-8.

4 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (unpublished second edition manuscript), Wilmer Fields entry.

5 Wilmer Fields, My Life in the Negro Leagues: An Autobiography (McLean, Virginia: Miniver Press, 2013), 39.

6 Kyle McNary, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe: 36 Years of Pitching & Catching in the Negro Leagues (McNary Publishing, 1994), Chapter 27, 1951.

7 Barry Swanton and Jay-Dell Mah, Black Baseball Players in Canada: A Biographical Dictionary, 1881-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2009), 162.

8 Orlin Jones, Detroit historian, telephone interview with author, March 23, 2022.

9 Swanton, 1.

10 Ron Teasley, telephone interview with author, June 21, 2019.

11 Michael Stahl, “The Secret History of Black Baseball Players in Canada’s Great White North,” Salon.com,April 30, 2017.

12 Jane Finnan Dorward, ed., Dominionball: Baseball Above the 49th (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2005), 100.

13 Swanton, 63-64.

14 Jim Adelson entry on NDAPSSA.com, accessed March 26, 2022; Dickinson (North Dakota) Press article, “Legendary ND Sportscaster Jim Adelson Dies at 91,” October 1, 2016; “Minot Mallards Memories” pages on AtthePlate.com, accessed March 26, 2022.

15 McNary, Chapter 27, 1951.

16 Email from Dan Kelly of Chatham, Ontario, to Andrew North, March 2, 2022; “Bucs Hold Camp at Thamesville,” Windsor Star, August 20, 1947; “Pirates Sign Bob Seguin,” Windsor Star, November 11, 1947.

17 Sporting News contract card image for Jim St. Louis, https://digital.la84.org/digital/collection/p17103coll3/id/146268/rec/29, accessed via SABR.org and downloaded March 4, 2022.

18 Author assessment after email correspondence over several years with Dr. Ted Turocy about quality of the “Open”-classification Pacific Coast League in 1950s.

19 “MLB Officially Designates the Negro Leagues as ‘Major League,’” December16, 2020, MLB press release posted on MLB.com, accessed December 16, 2020.

20 Riley, passim.

21 Scott Simkus, Outsider Baseball Bulletin, Issue Nos. 53-58, June 8-July 13, 2011.

22 Multiple conversations and emails between Pete Palmer and the author dating back to 1992.

23 Robert L. Finch, et al., eds., The Story of Minor League Baseball (Columbus, Ohio: National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues, 1952), 38, 45.

24 Swanton, 135.

25 Swanton, 3.

26 Swanton, 3, 135-136.

27 Swanton, 63.

28 Swanton and Mah, 65.

29 Fields, 31-32.

30 Swanton, 24.

31 McNary, Chapter 27, 1951.

32 Frazier “Slow” Robinson, Catching DREAMS: My Life in the Negro Baseball Leagues (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1999), 168-169.

33 Paul Dickson, ed., Baseball’s Greatest Quotations, Revised Edition (New York: Collins, 2008), 42.

34 Swanton and Mah, 43.

35 Swanton, 94.

36 Swanton, 118-119.

37 Swanton, 63.

38 Swanton, 130-131.

39 Swanton, 130-131.

40 https://mbhof.ca/inductees/ian-lowe/, accessed March 2, 2022.

41 http://honouredmembers.sportmanitoba.ca/search.php?criteria_name=lowe&criteria_sport=&criteria_keywords=&criteria_induction, accessed March 2, 2022.

42 Swanton, 146.

43 Gary Gillette and Pete Palmer, eds., The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition (New York: Sterling, 2008), 1722-1727.

44 www.42for21.org/results, accessed February 28, 2022.

45 Swanton, 63.

46 John Paul Hill, “The ManDak League: Haven for Former Negro League Ballplayers, 1950-1957 (review),” NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture 16, No. 1 (Fall 2007): 142.

47 “Campbells Beaten,” Edmonton Journal, March 15, 1957: 20.

48 “Bismarck Awarded Mandak [sic] Playoffs,” Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, August 28, 1957: 23.

49 BallparkDigest.com attendance reports for 2019 and 2021. Accessed February 20, 2022.

50 Dorward.