The Turbulent ’70s: Steinbrenner, the Stadium, and the 1970s Scene

This article was written by Tony Morante

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Big Apple (New York, 2017)

Any way you look at it, the 1970s was a decade of upheaval and change everywhere in the country, but particularly in New York City. The “police action” of Vietnam ended and an era of urban decay began. The personal computer arrived, the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center became the world’s tallest buildings, and Watergate was front page news. President Ford to NYC: “Drop Dead.” The “Son of Sam” terrorized the City. The NYPD went on strike. There was a blackout of the entire city’s electrical power. Arson was shown nationwide during the World Series. All of this to the strains of “disco fever” emanating from the infamous Studio 54.

I witnessed all of it from the Bronx, where I had been working for the New York Yankees since 1958. Talk about a decade of change: I’d started as an usher in the original Yankee Stadium and by the end of the 1970s I was the renovated Stadium’s official tour guide. Yankee Stadium was well on the way to becoming the mecca for outdoor events in the United States, but the stark realization was beginning to sink in that nearly five decades of wear and tear since Ruth’s day was taking a toll on the superstructure. Furthermore, “Yankee Village,” the neighborhood surrounding the Stadium, was in decline. “The realistic truth is that people won’t go there anymore because it is not a nice place to go,” claimed Dick Young of the New York Daily News.

I witnessed all of it from the Bronx, where I had been working for the New York Yankees since 1958. Talk about a decade of change: I’d started as an usher in the original Yankee Stadium and by the end of the 1970s I was the renovated Stadium’s official tour guide. Yankee Stadium was well on the way to becoming the mecca for outdoor events in the United States, but the stark realization was beginning to sink in that nearly five decades of wear and tear since Ruth’s day was taking a toll on the superstructure. Furthermore, “Yankee Village,” the neighborhood surrounding the Stadium, was in decline. “The realistic truth is that people won’t go there anymore because it is not a nice place to go,” claimed Dick Young of the New York Daily News.

If it weren’t for Mayor John Lindsay, the 1970s might have been the final decade of the Yankees in the Bronx. Other sites were proposed for a new stadium. New Jersey lured Stadium tenants the New York Giants football club to the Meadowlands, where a new home for them opened in 1976. But Mayor Lindsay struck a deal with New York City to perform a major renovation: it would cost around $28 million and require the team and the offices to temporarily relocate to Shea Stadium, home of the Mets, for two years.

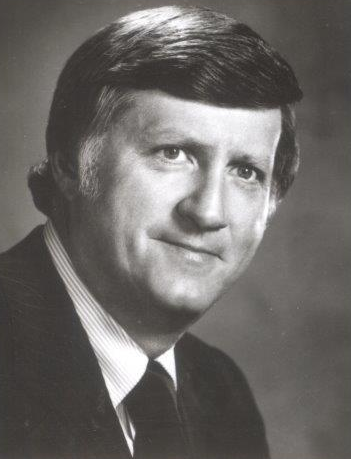

Of course a major player in the renovation deal was the newly minted owner of the Yankees, Mr. George M. Steinbrenner. As Sam Roberts of the New York Times reported, “Mr. Arthur R. Taylor, president of CBS, unloaded the New York Yankees in 1973. He oversaw the sale of CBS’s share of the Yankees to a group of investors led by George M. Steinbrenner for $10 million. CBS had purchased 80 percent of the team for $11.2 million in 1964.” In 1966, the team finished last in the American League for the first time since 1912, and the team struggled, rarely ranking higher than fourth by the time CBS sold its share.

A highly decorated WWll veteran (OSS agent, Navy Cross and the Silver Star), CBS vice president Michael Burke had been instrumental in purchasing the Yankees for CBS through his friendship with Yankees co-owner Dan Topping. Although Burke was promised the president’s role to stay on with the team, a buttoned-up Steinbrenner was not appreciative of his appearance, putting Burke on a slippery slope to his ouster. Burke was gone by April 1973, manager Ralph Houk and general manager Lee MacPhail by the end of the year.

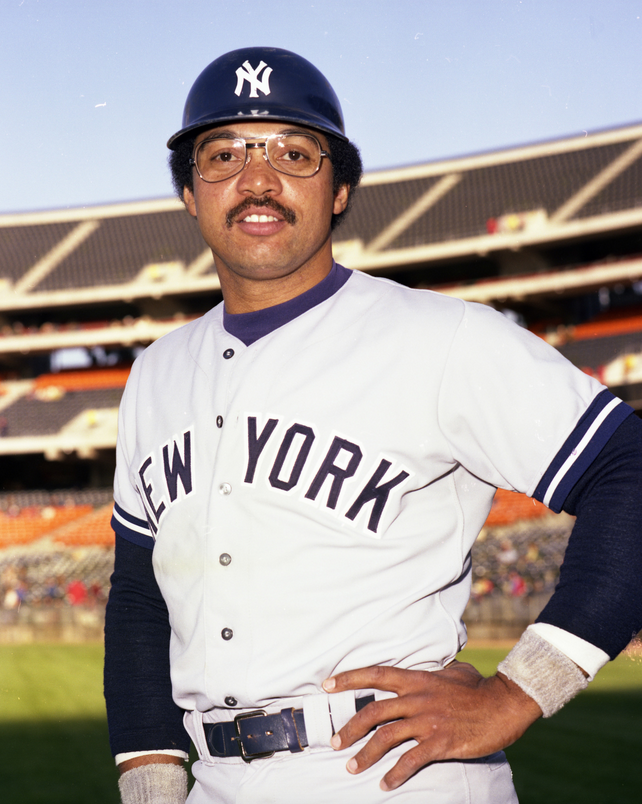

Perhaps the greatest acquisition of the Steinbrenner era was not, as one might think, a great ballplayer, but a savvy baseball veteran of over four decades, Indians general manager Gabe Paul. Shortly before he left Cleveland to come to the Yankees, he traded Graig Nettles to the Yankees for a few nondescript players. After coming to the Yankees he brought in Chris Chambliss, Dick Tidrow, and Oscar Gamble from his former club. He also got Dock Ellis from the Pirates, Bucky Dent from the White Sox, and acquired key players Lou Piniella, Mickey Rivers, Ed Figueroa, Willie Randolph, and Ken Brett. Another major upheaval of the decade: the introduction of free agency to major league baseball. On New Year’s Eve of 1974, Paul signed Catfish Hunter, who had been declared a free agent in arbitration by Peter Seitz. Paul also signed free agent Reggie Jackson in 1976.

The face of the game had also changed with the controversial 1973 adoption of the designated hitter rule by the American League, and as it happened the first appearance of the DH era was made by a Yankee, Ron Blomberg. The Stadium was such a locus of change that two Yankees players, Fritz Peterson and Mike Kekich, swapped wives and lives. The two left-handed starters were close friends and roommates on the road, and both men became enamored with each other’s wives. The subject of changing partners came up late in 1972 at a party in writer Maury Allen’s house. Six months later the deal was consummated as the two pitchers literally exchanged lives, kids, houses, and all, with each man moving into the other family’s home.

But as all that was occuring, the renovation of the Stadium loomed. What fans referred to as the Stadium’s “aura and mystique”—the lingering light of the great ballplayers, the great personalities, and the great events that were held here—would end for good on September 30, 1973, with the final game of the season.

The closing of the Stadium’s doors opened another door in our pop culture: collectibles. Everybody wanted a piece of this historic edifice! Gabe Paul offered a token of appreciation to the approximately 6,000 season ticket holders by giving them actual Stadium chairs which were removed by the Invirex Demolition Co. Only around 4,000 ticket holders’ chairs were accounted for. The rest were put on sale to the public. Department store E.J. Korvette managed to get a boatload of the chairs and sold them at $7 each. A few hundred also made their way to War Memorial Stadium, a minor league ballpark in Greensboro, North Carolina, where the seats were in use until that stadium was renovated in the early 1990s. In one case of appreciation for Stadium memorabilia, collector-author Bert Sugar signed two checks, each $1,500, made payable to the New York Yankees to appropriate some of the artifacts that were left behind. In a very short time some of the removed artifacts, including the chairs, were selling for thousands of dollars.

With reconstruction completed, the Yankees returned to their newly refurbished Stadium in 1976. The major renovations included a cantilevered support system which required 106 cables that surrounded the Stadium, replacing the obstructive girders that supported the mezzanine and upper level. The hard wooden seats were replaced with softer plastic seats. A new mercury-vapored lighting system replaced the banks of lights that had been installed in 1946.

With reconstruction completed, the Yankees returned to their newly refurbished Stadium in 1976. The major renovations included a cantilevered support system which required 106 cables that surrounded the Stadium, replacing the obstructive girders that supported the mezzanine and upper level. The hard wooden seats were replaced with softer plastic seats. A new mercury-vapored lighting system replaced the banks of lights that had been installed in 1946.

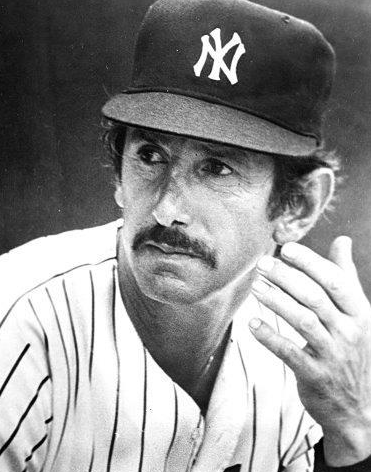

In 1975, Steinbrenner felt that the more genteel nature of manager Bill Virdon had to give way to the fiery Billy Martin, who had been fired by the Texas Rangers. Steinbrenner and Martin were two ego-centric personalities headed for much volatility. Martin’s ensuing multiple firings and re-hirings became a soap opera unto itself.

Volatile as the personalities at the top were, talent pushed the Yankees to the top of the league in 1976. “After so many years without postseason play, the ’76 pennant was an enormous relief,” recalled Marty Appel, then the team’s public relations director. “But after the World Series loss to Cincinnati, there was a greater determination than ever to finish the job. Mr. Steinbrenner had instilled a winning attitude that extended even to the front office. We were going to be all-in for 1977. Eyes on the prize.” Chris Chambliss’s dramatic home run against the Kansas City Royals had brought the Yankees back from anonymity after a 12-year-long hiatus from the postseason and had made a prophet out of Mr. Steinbrenner. Unfortunately, they ran into a hot Cincinnati Reds team—a.k.a. the Big Red Machine—that swept them in four games. All through this season, Thurman Munson, catcher and the newly named captain of the Yankees, continued to cement his position as the backbone of the team. He was awarded the AL MVP honors. But Munson’s position as clubhouse top dog was about to be challenged. In November of 1976, Reggie Jackson was added to the already combustible mixture of characters with a five-year contract worth $2.96 million. The Boss cavorted all around the Big Apple with Reggie for three weeks. Munson was none too happy to hear the details of the contract; after all, he had been told that he would be the highest paid Yankee by Mr. Steinbrenner.

In May 1977 an interview with Jackson appeared in Sports Illustrated with the infamous quote, “I’m the straw that stirs the drink, Munson thinks that he can stir the drink, but he can only stir it bad.” Munson took it badly. Teammates rallied to Munson as he was respected as the heart and soul of the team. Relations were strained all around.

Murray Chass of the New York Times tells the tale: “After Martin had benched Jackson a couple of times bigger trouble followed. Matters continued to deteriorate when it all exploded in Fenway Park on June 18th. When Jackson seemingly loafed after a hit to right field Billy Martin sent Paul Blair out to replace him. This was a great embarrassment to Jackson who felt that Martin never liked him in the first place. After Jackson reached the dugout the two antagonists continued to berate each until they were separated by Elston Howard and Yogi Berra. All of this occurred while the game was being nationally televised giving the audience a taste of what was going on in Yankeeland. The Boss was irate!”

Murray Chass of the New York Times tells the tale: “After Martin had benched Jackson a couple of times bigger trouble followed. Matters continued to deteriorate when it all exploded in Fenway Park on June 18th. When Jackson seemingly loafed after a hit to right field Billy Martin sent Paul Blair out to replace him. This was a great embarrassment to Jackson who felt that Martin never liked him in the first place. After Jackson reached the dugout the two antagonists continued to berate each until they were separated by Elston Howard and Yogi Berra. All of this occurred while the game was being nationally televised giving the audience a taste of what was going on in Yankeeland. The Boss was irate!”

Across town, the Mets showed they were not immune to drama, either. The greatest ballplayer in the Mets’ young 15-year history—pitcher Tom Seaver, who was called “The Franchise” by the Mets’ chairman of the board, M. Donald Grant—become embroiled in a contract dispute. Grant felt that Seaver’s demand for a salary of $250,000 was nothing but greed. Seaver was traded to Cincinnati for four nondescript ballplayers. Mets fans were heartbroken.

Despite daily brush fires with the Boss, Martin, and Jackson, the Yankees won the pennant, once again beating Kansas City, then bested the Dodgers in six games in the World Series. In the clincher, Reggie electrified the Stadium crowd by hitting three home runs on three consecutive pitches off three different pitchers. He won MVP honors for the Series. The victory was followed by a tickertape parade up the “Canyon of Heroes” (Broadway) which was thrilling for me to be a part of.

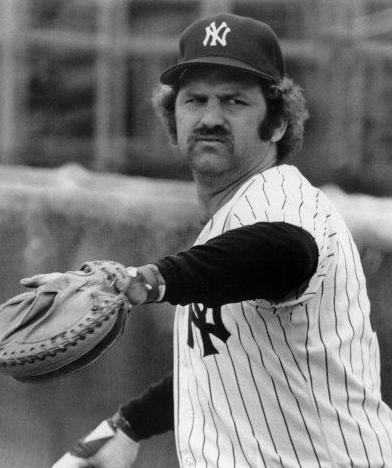

The drama didn’t end there. Reliever Sparky Lyle had been instrumental in the 1977 Yankees’ success, capped off with the Cy Young award, the first American League relief pitcher to achieve that distinction. The month after the parade, Mr. Steinbrenner picked up the hottest reliever on the free agent market in Goose Gossage—an embarrassment of riches and a crushing blow to Lyle. Lyle would spend a season playing an unhappy second fiddle to Goose and then was traded to Texas on November 10, 1978. Another major loss was occurring at this time. The architect of the Yankees’ success, Gabe Paul, resigned after the 1977 season and departed for Cleveland. Steinbrenner claimed Paul was getting too much of the credit for the player moves and the team’s success.

Opening Day 1978 started with another unforgettable event. Before Reggie ever came to the Yankees he had made a statement, “If I ever played in New York they would name a candy bar after me,” perhaps thinking that “Baby Ruth” bars had been named for Babe Ruth. Well. In a promotion with Curtis Candy Mfg., over 40,000 candy bars called “Reggie Bars” were issued to the fans entering the Stadium. In pure theatrical fashion, Reggie stepped up to the plate with two men on board and hit a home run. All of a sudden, the candy bars became missiles and they were launched from every part of the Stadium. It took the grounds crew half an hour to clean the field.

The main story line in 1978 was Ron Guidry’s great pitching. He won 13 games in a row from the start of the season, and on June 17, as he pitched against the California Angels, Guidry began to pile up strikeouts with his vicious slider. By the fifth inning fans started to rhythmically clap whenever he put two strikes on a batter, exhorting him to strike the batter out. Guidry, who was dubbed “Louisiana Lightning” by Yankees announcer Phil Rizzuto, wound up with 18 Ks on the day. The “two-strike clap” practice became commonplace at the Stadium after that.

Other than Guidry’s great performance, the team was really struggling. They had fallen 14 games behind the league-leading Boston Red Sox when the high drama returned. On July 17, Reggie—who had recently been made DH by Martin, and not too happy at all by it—disobeyed an order by failing to heed a sign by the third base coach. He was taken to task by Martin and suspended for five games. But Billy was also hearing it from The Boss, and blurted to a reporter, “He’s a born liar. The two of them deserve each other, one’s a born liar, the other’s convicted.” Martin appeared physically and emotionally drawn.

Martin decided to resign before being fired. His replacement was Bob Lemon, who had been fired from the White Sox. But five days after his tearful farewell, Billy and Steinbrenner engineered a moment of pure spectacle at the Old Timers Day Game. During pre-game introductions by public address announcer Bob Sheppard, Billy was squirreled away in the bowels of Yankee Stadium, ready to make a surprise appearance. Sheppard then delighted the crowd with the announcement that Martin would be returning as manager starting with the 1980 season “and hopefully for many years after that.” This was followed by a seven-minute standing ovation.

Boston started to tail off as the Yankees mounted a comeback. By early September the gap was down to four games with a four-game series at Fenway on the slate. In what came to be known as “The Boston Massacre,” the Yankees swept all four games, outscoring the Red Sox, 42–9. By season’s end both teams were tied in the standings, prompting a one-game playoff at Fenway. Many people call the Boston Red Sox/New York Yankees the “greatest rivalry in professional sports” because of moments like this one: Yankees shortstop Bucky Dent hit a three-run homer in the seventh inning to put the Yankees on top. Guidry ran out of gas and was replaced by Gossage who sealed Boston’s fate. The Yankees then beat the Dodgers again in six games to win the World Series.

In 1979, the decade drawing to a close, the Yankees were lingering around fourth place for most of the season. Another comeback was not in the making. A series of minor injuries and ailments to key players including Nettles, Jackson, Gossage, and especially to their captain, Thurman Munson, contributed to the mediocrity, but none could predict the tragedy that would strike.

In 1979, the decade drawing to a close, the Yankees were lingering around fourth place for most of the season. Another comeback was not in the making. A series of minor injuries and ailments to key players including Nettles, Jackson, Gossage, and especially to their captain, Thurman Munson, contributed to the mediocrity, but none could predict the tragedy that would strike.

As reported by Marty Appel in his book Munson: The Life and Death of a Yankee Captain, Munson’s career as a catcher was probably winding down by 1979, injuries having taken their toll. Munson had never spent a day on the disabled list. When a plane crash claimed his life on August 2, it really closed a chapter on the Yankees’ decade, a decade in which Munson went from Rookie of the Year to captain of a world champion ballclub. The appreciation of what he meant to the resurgent Yankees only grew over time. He had led them to the top of the baseball world, and had reconnected them to the team’s past glories, proudly taking his place in the lineage of great Yankee catchers. The team’s first captain since Lou Gehrig, he was firmly tied forever to Yankee heritage, and he remained an old school symbol of playing the game right. The fans saw through his gruff exterior to the soul of a champion. All these years later, his image still invokes grit and determination, a time when leadership was on display daily as he pushed his teammates towards glory.

Isn’t it fitting that peace came to Yankee Stadium on October 2 with a Catholic mass? Pope John Paul ll celebrated mass with 80,000 faithful followers, wrapping up the raucous decade.

TONY MORANTE, a SABR member since 1995, is the Director of Yankee Stadium Tours. He started working at Yankee Stadium in 1958 as an usher and came aboard full-time in 1973 in the Group/Season Sales Department. Morante, with the encouragement of then-principal owner, George M. Steinbrenner III, instituted the Yankee Stadium Tour program in 1985, bringing Yankees history to life for school children, visitors and employees’ orientations. Morante served in the United States Navy and he is currently involved with the Wounded Warrior Project and the Special Operations Program through the New York Yankees. Tony is a graduate of Fordham University and he is currently Adjunct Professor there teaching “Baseball: The New York Game.”

Sources

Appel, Marty. Munson: The Life and Death of a Yankee Captain, Anchor, 2010.

Appel, Marty. Pinstripe Empire, Bloomsbury, 2014.

Durso, Joseph. Yankee Stadium; Fifty Years of Drama, Houghton Mifflin, 1972.

Lyle, Sparky and Peter Golenbock. The Bronx Zoo, Crown Publishing, 1978.

Pepe, Phil. Talkin’ Baseball: An Oral History of Baseball in the 1970s, Ballantine Books, 1998.

Stout, Glenn and Richard Johnson. Yankees Century, Houghton Mifflin, 2002.

Sullivan, Neil J. The Diamond in the Bronx, Oxford University Press, 2001.

Yankee Stadium-The Official Retrospective. Pocket Books of Simon and Schuster.