Ty Cobb, Master Thief

This article was written by Chuck Rosciam

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 25, 2005)

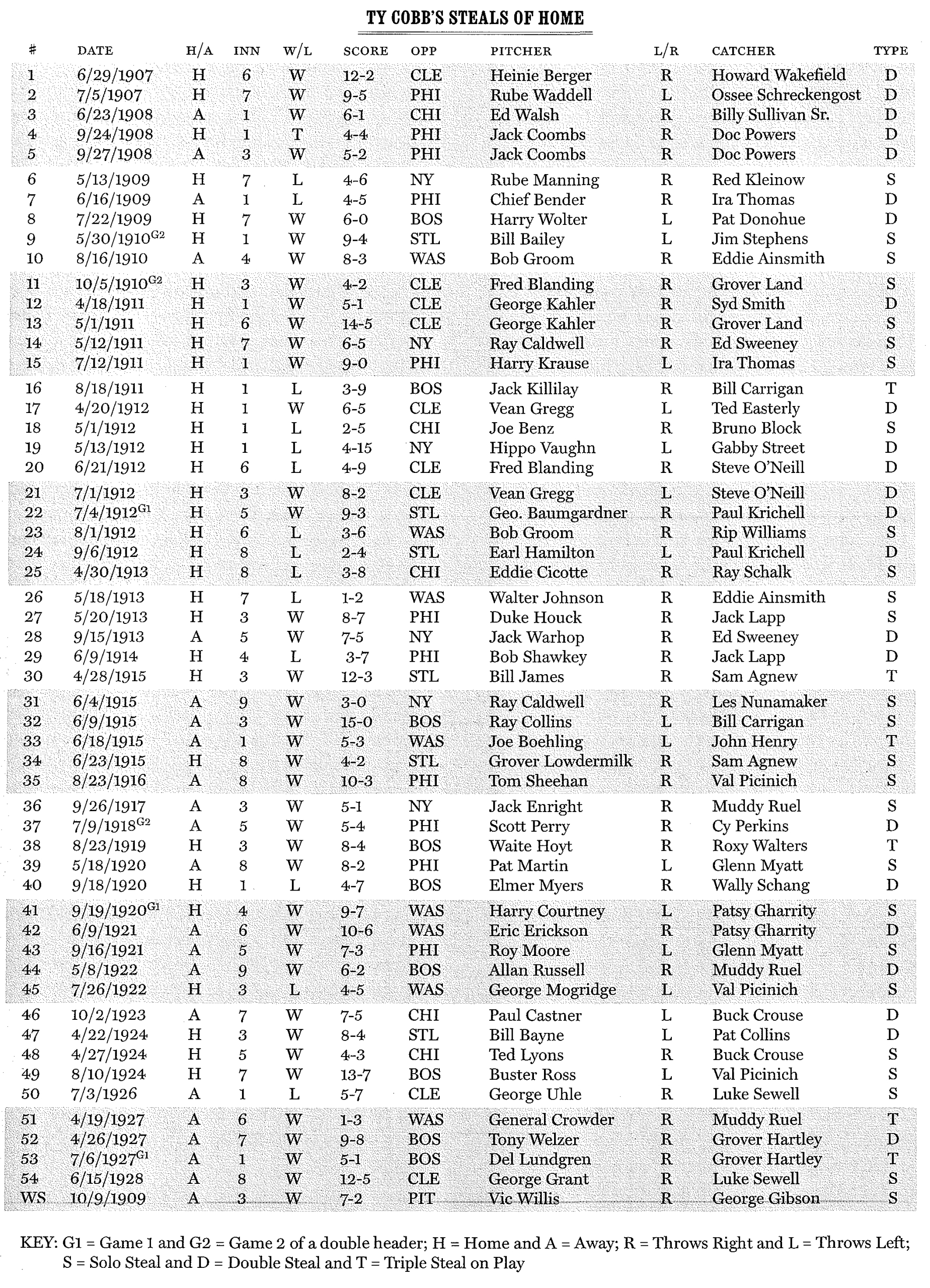

Even though the value of stealing bases can be argued, there is no dispute about the impact on a game’s outcome when a runner steals home. And one player, more than any other, can be considered the “Master Thief”: Tyrus Raymond Cobb. His record-setting career 54 steals of home (SOH) is a mark that may never be surpassed.

Only two players stole more than half of Cobb’s 54 total: Max Carey (33) and George Burns (28). Not even the all-time overall stolen base leader, Rickey Henderson, with his 1,406 thefts, could approach Cobb’s SOH total. Henderson stole home only eight times during his career. By comparison, Cobb stole home eight times in just one year alone (1912), setting the single-season major league record. The closest any player has ever come to Cobb’s seasonal SOH record is seven, reached by Pete Reiser in 1946 and Rod Carew in 1969.

Although Cobb never stole home twice in a game, a feat accomplished by 11 players, he did steal second, third, and home in one inning on four different occasions to set the major league record (July 22, 1909, July 12, 1911, July 4, 1912, and August 10, 1924). Only Honus Wagner with three such events came close to Cobb’s record. During the July 12, 1911, game versus the Athletics, Ty stole second base, third base, and home plate on consecutive pitches by left handed Harry Krause.

Which teams were the victims most often for Cobb’s SOH thievery?

- Philadelphia Athletics, 11

- Cleveland Indians, 9

- Boston Red Sox, 9

- Washington Senators, 8

- New York Yankees, 6

- St. Louis Browns, 6

- Chicago White Sox, 5

- Detroit Tigers, 0

It must have been gratifying to Philadelphia fans for Ty to leave the Detroit Tigers at the end of the 1926 season to join the Athletics, for which he subsequently stole home four times, twice against Boston and once each against Cleveland and Washington. Otherwise, the Philly total might have been higher.

Apparently, an opponent had to keep an eye on Cobb early on in a game. He was more aggressive in the early innings, stealing home 24 times in 46 attempts in the first three innings. From the seventh inning on, he was more responsible (and successful), swiping home 16 of 19 tries-an amazing 84%. The breakdown by inning for Cobb’s steals of home are:

- 1st, 14

- 2nd, 0

- 3rd, 10

- 4th, 3

- 5th, 5

- 6th, 6

- 7th, 8

- 8th, 6

- 9th, 2

Of Cobb’s 98 regular-season dashes for home, two thirds occurred with two outs. Of these 66 “all-or nothing” attempts, he was successful half of the time (33). He made 28 attempts with one out; 18 were successful for a decent 64%. Only four of his attempts were with none out, and he was successful the first three times he tried it. His 54 steals of home out of 98 attempts (a 55% success rate) is far above latter-day base stealers, who manage only a 37% success story.

Which backstops suffered the most humiliation? That dubious distinction goes to Val Picinich (Philadelphia, Washington, and Boston) and Muddy Ruel (New York, Boston, and Washington), who were stung three times each. Ruel was the victim with the longest span of time (1917 and 1927) with a third one thrown in the middle years (1922). Cobb used to love taunting the catchers. He would routinely shout at them that he was going on the next pitch, which he usually did. Although Ty never did steal home against Lou Criger, he was a favorite backstop to taunt and run against.

Several pitchers were the victims twice (Jack Coombs, Bob Groom, George Kahler, Ray Caldwell, Vean Gregg, and Fred Blanding). Coombs became a victim just three days apart in 1908. Although it’s generally believed to be easier to steal home on a southpaw because his back is turned to third base, fewer than one-third (17) of Ty’s successful thefts came off left handers.

Throughout his entire career Ty kept the opposition guessing whenever he was on base. He stole home in each month from April to October in almost equal proportion to the number of games he played.

- April, 8

- May, 10

- June, 11

- July, 9

- August, 6

- September, 8

- October, 2

Cobb’s first steal of home occurred when he was age 20, and his last one was at the ripe old age of 41, during a season in which he stole only five bases. Ty stole home 26 times in a solo effort, 23 times as the front end of a double steal, and six times as the front end of a triple steal. These are records that have never been approached. One of the triple steals resulted in catcher John Henry being spiked on his throwing hand on the play (June 18, 1915), which was a hazard often suffered when Ty stole home.

One of Cobb’s most original steals of home took place in a home game on May 12, 1911, against New York. Detroit trailed 5-3 in the seventh with two outs and men on first and second when Ty slammed a two-bagger to left field. The runner at second scored easily, and the man on first dashed toward home. The left fielder threw to the plate to cut down the runner. Cobb stopped on second. The runner slid across the plate and was called safe. The catcher, Ed Sweeney, began a protest with his infield flocking around him and the umpire. Even though it was customary for any base runners remain in place until matters were settled, Cobb trotted to third; no one saw him. He then tiptoed toward the group at the plate; still he remained unobserved. Peering into the cluster of disputants for an opening to slide through, he found one and skated across the plate with the winning run under the noses of almost the entire Yankee team.

The 17th career steal of home by Cobb was the very first run ever scored by Detroit in their new stadium, Navin Field. It happened on April 20, 1912, in the bottom of the first inning when Ty, timing the Cleveland pitcher Vean Gregg’s delivery perfectly, took off from third base and hook-slid around the lunging catcher, Ted Easterly.

On July 12, 1911, just after his 40-game hitting streak, Ty was responsible for four runs in a 9-0 win against Philadelphia without even a hit. In the first inning, he walked and stole the next three bases, twice beating perfect throws by catcher Ira Thomas. A fielder’s choice and a run scored on Sam Crawford’s homer plus a sacrifice fly accounted for two more. In the seventh frame he walked and came all the way around on a Crawford sacrifice to score by knocking the ball from the hands of the new catcher, Paddy Livingston.

Cobb’s only theft of home in 1917 came at the end of the season (September 26) when he was tied with Eddie Collins for the overall stolen base leadership with 53 steals. The SOH that day gave him the league lead for the season, which he increased in the next week by swiping one more base, to finish the year with 55 thefts to Collins 53.

Ty was partial to the home field, where he stole home 34 of the 54 times. His thefts occurred in a winning cause 40 times, of which six steals resulted in a one-run victory for his team (Detroit). He was more likely to try to pilfer home with his team ahead (28 steals in 53 attempts) than with his team behind (14 steals in 27 attempts). With the score tied, he was successful on 12 of 18 attempts.

Five of his 14 first-inning thefts came with two outs and the clean-up hitter, Sam Crawford, batting. In three of those five games, the pitcher was so unnerved by the steal of home that he tossed a sitting duck to the batter, who promptly knocked one into the stands. Many times, with Cobb on third base, Sam Crawford would draw a walk, trot down to first base, and then suddenly speed up and round first base as fast as he could toward second. The battery would be watching Cobb and wouldn’t know what to do. If they tried to stop Crawford, then Cobb would take off for home. Sometimes they caught Ty and sometimes they’d catch Sam and sometimes they wouldn’t get either. Most of the time they were too paralyzed to do anything, and Crawford wound up at second on a base on balls. Such was the threat of Cobb stealing home.

Age did not slow down the Georgia Peach. Thirteen of his 54 SOHs came after the age of 35. As an example, his 52nd robbery at age 40 demonstrated that. He was the whole show during the game as the Athletics overcame a six-run lead to beat the Red Sox. Not only did he steal home, he drove in two runs, scored twice himself, and ended the game with a circus catch and an unassisted double play by coming in from right field to tag the runner at first.

His last steal of home was memorable. Cartoonists of the day depicted Cobb as an aging old man with a graybeard growing down to his waist and walking with a cane. On June 15, 1928, at Cleveland, Ty demonstrated how much he had left.1 It began in the eighth inning, when he hit a grounder to first base that was bobbled by Lew Fonseca. Cobb went right on past first and on to second safely. On a groundout by Max Bishop, he advanced to third. Then he caught pitcher George Grant off guard and a roar from the crowd went up—”There he goes!” Before catcher Luke Sewell could handle Grant’s snap throw and apply the tag, Cobb was in safely.

The regular season was not the only time that Cobb performed his derring-do. During game two of the 1909 World Series, Ty stole home in the third inning to break open the game. Pirate pitcher Vic Willis was making his debut, in relief of starter Howie Camnitz, and before he could retire the first batter he faced, Cobb stole home with catcher George Gibson unable to stop him.

Because Cobb mastered all of the tools of the trade he made himself into one of the greatest base runners of the game. By his own admission he was not the fastest runner. He was the smartest and most aggressive thief. During his entire career he studied every pitcher’s delivery, and he invented the fall-away slide maneuver, which completely fooled basemen. Furthermore, he tricked his opponents into traps and throwing errors, plus feigned injuries to lull the defense into forgetting about him.

A hundred years ago (September 12,1905), Ty Cobb stole his very first base, and for the next 24 seasons he proceeded to steal 896 more to set the modern record subsequently broken by Lou Brock (938) and then Rickey Henderson (1,406). However, Cobb’s 54 steals of home far overshadow the combined SOH totals of Lou Brock, Rickey Henderson, Rod Carew, and Paul Molitor—all of which are considered premier base stealers. In addition, no one has come close to Cobb’s record of stealing three or more bases in a game 37 times. He is undoubtedly the “master thief” of baseball.

CHUCK ROSCIAM is a retired Navy Captain with 43 years active service. A SABR Member since 1992, he also created baseballcatchers.com and tripleplays.sabr.org.

(Click image to enlarge)

Sources

Identifying and documenting Cobb’s steals of home and stealing second, third, and home in an inning is a work in progress, and the research is incomplete. The above list represents the latest research following cumulative efforts of SABR members over the years, most notably Bob Davids. It is the most accurate compilation from available sources.

Stump, Al. Cobb: A Biography (Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin, 1994) pp. 421-422, appendix list of 35 SOHs. Bak, Richard. Ty Cobb: His Tumultuous Life and Times (Dallas, TX: Taylor, 1994) pp.90-91, list of 54 SOHs.

The Sporting News Complete Baseball Record Book, 2003 ed., p.75 and p.179, lists Cobb as having stole home only 50 times. Also p.75 lists Cobb as stealing second, third, and home in a single inning four times with the years: 1909, 1911, 1912 (2). Only 1909 and 1911 have been confirmed by box scores. One 2-3-H feat in 1912 was noted by Charles Alexander in his book on p.107 and in Richard Bak’s book p.84.

Joe Reichler’s The Great All-Time Baseball Record Book, 1991 ed., lists Cobb as stealing second, third, and home in a game six times (not necessarily the same inning): 9/2/1907, 7/23/1909, 7/12/1911, 7/4/1912, 6/18/1917, 8/10/1924. In three of those games (1907, 1909, and 1917) Cobb did not do it as confirmed by box scores.

Davids, Bob. “‘Ty Is Still Stealing Home,” The Baseball Research Journal, 1991, p. 40.

Retrosheet & David Smith, SABR Member, confirmed by the box score of the game of 7/22/1909.

Palmer, Pete and Gary Gillette, eds. The Baseball Encyclopedia, New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2004. p. 1623 identifies Cobb with 897 career stolen bases.

Alexander, Charles. Ty Cobb (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984), p. 207, career SOHs 35.

Mouch, Warren. “Ty Cobb Steals Home!” Baseball Historical Review, 1981 reprint of 1972 article, pp. 48-51. Washington Post box scores with write-ups for 13 games confirming steals of home.

New York Times box scores with write-ups for 10 games confirming steals of home.

Chicago Tribune box scores with write-ups for nine games confirming steals of home.

Detroit Free Press, April 21, 1912, reporting first run scored at Navin Field by Cobb’s steal of home. www.baseball-reference.com/c/cobbty01.shtml source for Cobb’s career stats.

Official scorers during Cobb’s time did not record a stolen base of home on a passed ball or a wild pitch when the attempt was made before the pitch was delivered. Had Rule 10.08(a) been in effect, Cobb would have had at least six more steals of home.

Trent McCotter, SABR member, verified or disavowed Cobb’s 2-3-H steals in an inning from his database, which contains every game Cobb played in his career, including stolen base totals.

Other SABR members who contributed confirming and/or verifying information: Bill Deane, Steve Hoy, Dennis VanLangen, Jim Charlton, Francis Kinlaw, Bill Dunstone, Joe Murphy.

Notes

1 The original version of this article published in 2005 said the June 15, 1928 game at Cleveland had “crowds estimated as the largest in the game’s history—up to 85,000.” This is incorrect. The crowd at Cleveland’s cozy League Park on June 15, 1928 was estimated to be about 2,500 fans.