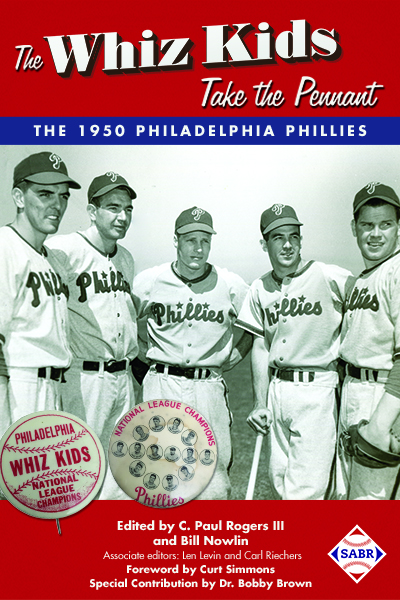

Whiz Kid Fan for Life

This article was written by Dennis Brislen

This article was published in 1950 Philadelphia Phillies essays

It started with a radio broadcast and a baseball glove.

It started with a radio broadcast and a baseball glove.

In late 1946 my father, my pregnant mother, and I lived in Chicago with my grandparents. World War II over and business picking up, my father decided to request – actually, I was told later, it was more a demand – a transfer to his insurance company’s new plum branch office in Dallas. A few days later he was told he would be transferred … to Pittsburgh, effective January 2, 1947. Not the message he hoped to receive. There, after six months, he had a new job with a company in Philadelphia.

Upon our arrival at our new home, I promptly got the measles and was quarantined. Nothing for a 6-year-old to do but read and listen to the radio. While turning dials I was entranced by the background crowd noise of a baseball broadcast and soon heard the voice of the play-by-play announcer Byrum Saam. I was hooked. Quarantine over, I quickly made friends in the neighborhood and began pestering my dad for a baseball glove.

For the next three years I listened to Saam broadcasting the Phillies and Athletics home games. At that time in ’47, Philadelphia was still an A’s town and the meme was “one more pennant for Mr. Mack.” They came close in 1948, remaining in the race until September.

At the same time the Carpenter family was putting lots of money into the Phillies franchise and manager Ben Chapman was receiving praise for putting a hard-nosed team on the field. It was something Phillies fans hadn’t seen very often over the decades. Though I enjoyed the A’s games, for some reason I was more attracted to the Phillies. My dad eventually fulfilled my wish for a baseball glove when he gave me a new first baseman’s mitt with an Eddie Waitkus signature. In 1949 the Phillies acquired Waitkus in a trade with the Cubs, making it official. I was a Phillies fan.

In 1948 I went to my first game. My grandfather visited us from Chicago and took me to a night game at Shibe Park. August 18, 1948. By now Chapman had been fired and replaced by Eddie Sawyer. The Phils sent a talented right-handed bonus baby named Robin Roberts against the hated Brooklyn Dodgers. Of course I did not realize then that I was witnessing a future Hall of Famer who would become my greatest sports hero.

As many have related, the emerald green field reflecting off the lights is something no baseball fan ever forgets. Roberts gave up an unearned run in the first when he made a wild pickoff throw to second base that allowed the runner to advance to third, from where he scored on a Roberts wild pitch. I wasn’t too concerned, lots of game left. Yeah, right. The Phillies got only one hit and were handcuffed by Rex Barney, the Dodgers pitcher, for a tough 1-0 loss. I got an introduction to the Philly boo birds in the bottom of the ninth when Barney closed out the game by striking out the side. After the final strikeout the boos were thunderous. Welcome to Philly fandom, young fella. To make it worse, my grandfather teased me about our inept offense on the drive home. But the beauty of youth is reflected by optimism. I quickly bounced back.

By the end of 1949, Philadelphia was on the verge of becoming a Phillies town. Though Mack’s A’s finished 81-73, it was good only for fifth place, while the Phils’ blend of youth and veterans was paying off with a third-place finish. We youngsters were fascinated with them. Comparing the A’s and Phillies at that time reminds me of the mid-’50s when rock and roll supplanted pop music. The Mack Men seemed like the aging old guard being upstaged by the youngsters.

An interesting side note occurred during the 1949-50 offseason. It was announced that for the first time radio would broadcast both teams home and away. The big question was which team By Saam would broadcast for? Saam was a fixture, very popular and there was a lot of speculation. When Saam was assigned to the A’s, I remember many people saying that the Phillies would never be able to find someone as good. But soon the Phillies announced the hiring of a 38-year-old broadcaster named Gene Kelly. As I recall, the first time we heard him was at the end of spring training when the two teams played a three-game exhibition City Series at Shibe Park. I remember that By Saam introduced Kelly and Gene responded by thanking Saam for all his help in getting acclimated to Philadelphia. It was gracious and well done by both men. Both had terrific radio voices. Though the advertising people carried a lot of weight, that era was thankfully free from announcers who felt the need to hype every play beyond its significance.

In any event, the transition was seamless and by the middle of May, Kelly was the “Voice of the Phillies” and By Saam was left to broadcast the hapless A’s.

Television was in its infancy and few had a set. Perhaps one family or two per block, though this was changing rapidly as prices came down. The Phillies televised a few games, a half-dozen or so. I saw my first TV game in September, the day-night doubleheader when Don Newcombe started both games. The televised game featured Curt Simmons in his next to last start before leaving for active duty with his National Guard unit. Simmons simply overpowered the Dodgers for 8⅓ innings before being relieved by Jim Konstanty with a 2-0 lead. This night, however, Konstanty didn’t have it and the Dodgers scored three runs to win the game and sweep the doubleheader. I took this hard. It was the first time I second-guessed Sawyer, which was pretty dumb considering how well Konstanty had pitched all season. But I hated to see Simmons lose a beautifully pitched game. A bad sign even though, with the Phillies still in first place, the pennant race looked very good.

The two dailies, the Inquirer and Evening Bulletin, were our must-reads. The beat writers were guys like Ray Kelly (no relation to Gene), Frank Yeutter, Stan Baumgartner, and Allen Lewis. They were all veterans except Lewis, who was early in a long career. Baumgartner had been a pitcher for the A’s in the 1920s and wasn’t shy about reminding people. I remember a few parents remarking that some of the players didn’t trust him. There later was a rumor that Baumgartner withheld his MVP vote in 1952 when Roberts won 28 games because he didn’t think it should go to a pitcher.

Nevertheless, we always turned to the sports pages first thing every day. As the 1950 season wore on, the excitement became palpable. It’s genuinely difficult to convey the effect the Whiz Kids had on the city at a time when major-league baseball had no competition as America’s National Pastime. Old and young alike, including some who had never before known a baseball from a grapefruit, were riveted to each broadcast. Phillies caps, jackets, anything with a “Fightin’ Phils” insignia sold out. When we played pickup games we argued over which player we would be. Many wanted to be Puddinhead. The nicknames were magical, Whitey, Granny, Ding Dong Del, Robby. They became like family. Of course we were Philadelphia fans, so on the rare occasion there was a screw-up, Ashburn could quickly become “Assburn” and Granny would become “Grandma.” But these were mere childish disappointments and mistakes were soon forgiven.

I had been pestering my parents for a paper route and when they finally gave in I began delivering the Evening Bulletin in May of 1950.

Bad timing.

It required me to work my route each afternoon at the time of the Phillies’ day broadcasts. It was before transistor radios and I came to hate having to leave in the middle of a game to do the route. I put my 10-year-old mind to work and, realizing that most on the route were listening to the game, I would personally go to the door and hand them the paper and get the game update. After a couple of weeks, as the summer heat came, those without air-conditioning (most) would have their windows open and when they saw me coming would turn up the broadcast and often come to the door to update me. I didn’t even have to get off my bike.

We were all in this together.

At school we sang the theme song, “Fight, fight, fightin’ Phils” until our teachers begged us to stop. School-bus drivers kept us in line by encouraging Phillies chants; there was not a waking hour that didn’t at some point revolve around the Phillies. The dinner table was a nightly ritual: discuss the afternoon game or predict that evening’s game. If there was an off-day, we discussed the league schedule. I cannot remember any discussion of the A’s. It was as if they didn’t exist.

Although much has been written about the final two weeks of the season, suffice it to say that for us youngsters it was an agonizing lesson in a class named Hopes and Fears 101. It was difficult to realize our heroes were human. They were making bad plays, leaving runners on base, and just when the most optimistic of us was ready to concede, Ashburn, Roberts, and Sisler came to our rescue.

I of course was disappointed with the World Series against the Yankees, but like most of Philadelphia, expected we would be back again. Though it never happened, the Whiz Kids have remained in my heart for better or worse. They were, after all, proof that magic was real, dreams could come true, the good guys could win, even if only once.

DENNIS BRISLEN is a retired airline worker who lettered in small college intercollegiate sports and was a former semipro baseball player and manager. He also had a 25-year career in high school and NAIA college coaching and officiating. He is a lifelong Phillies fan and self-proclaimed Whiz kid fanatic. In 1951 his family moved from Philadelphia to Chicago where he was able to continue his fanaticism by watching often the Whiz Kids at Wrigley Field. He has published his memories of youth baseball in Growing Up with Baseball and internet blogs. He counts among his biggest life failures his inability to deter his son from becoming an Atlanta Braves fan. This is somewhat assuaged by the fact that at least it’s not the Dodgers.