Why is the Shortstop ‘6’?

This article was written by Keith Olbermann

This article was published in SABR 50 at 50

This article was published in SABR’s Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 34 (2005).

As a baseball artifact, it’s pretty special as it is.

As a baseball artifact, it’s pretty special as it is.

It’s a scorecard from August 5, 1891 — a day when Buck Ewing drove in four runs off Cy Young and the New York Giants managed to hold off the Cleveland Spiders, 8–7, at the Polo Grounds. The book still shows the partial vertical fold its original owner might have created while stuffing it into a pocket as he raced to catch the steam-powered elevated train that would take him back downtown. And the scorecard pages themselves tell of a Cleveland rally thwarted only in the last of the ninth, when Spiders player-manager Patsy Tebeau, rounding third base, passed his teammate Spud Johnson going in the opposite direction — running his team into a game-ending double play.

The program is actually an embryonic yearbook. There are 14 photos and biographies of Giants players, and a wonderful series of anonymous notes under the heading “Base Hits” (“Anson next week. If we win three straights [sic] from him, we will be in first place”). But amid all the joyous nostalgia of a time impossibly distant — stuffed between the evidence that the owner saw Cy Young pitch in his first full major league season — hidden among the ads that beckon us to visit the Atalanta Casino or try Frink’s Eczema Ointment or buy what was doubtlessly an enormous leftover supply of Tim Keefe’s Official Players League Base Balls — we can throw everything out, except the top of page 10.

There, in six simple paragraphs, the scorecard’s buyer is advised how to use it. “Hints On Scoring” tells us, simply, “On the margin of the score blanks will be seen certain numerals opposite the players’ name . . . . The pitcher is numbered 1 in all cases, catcher 2, first base 3, second base 4, short stop 5, third base 6.”

This is no mistake caused by somebody’s over-indulgence at the Atalanta Casino.

The unknown editor offers a few sample plays, including: “If a ball is hit to third base, and the runner is thrown out to first base, without looking at the score card, it is known that the numbers to be recorded are 6-3, the former getting the assist and the latter the put-out. If from short stop, it is 5-3. . . .”

If we need any further confirmation that more has changed since 1891 than just the availability of Frink’s Eczema Ointment, the scorecard pages themselves provide it. In the preprinted lineups, third basemen Tebeau of Cleveland and Charlie Bassett of New York each have the number “6” printed just below their names. And the two shortstops, Ed McKean of the Spiders and Lew Whistler of the Giants, each have a “5.”

We may view the system of numbers assigned to the fielding positions as eternal and immutable. But this 1891 Giants scorecard suggests otherwise, and is the tip of an iceberg we still don’t fully see or understand — a story that anecdotally suggests a great collision of style and influence in the press box, no less intriguing than the war between that followed the creation of the American League.

The shortstop used to be “5,” and the third baseman used to be “6.”

We do not know precisely how and when it changed — there is a pretty good theory — but we do know that by 1909, the issue had been decided. In the World Series program for that year, Jacob Morse, the editor of the prominent Base Ball Magazine, gets seven paragraphs — the longest article in the book — to offer not “Hints On Scoring” but the much more definitive “How To Keep Score.” And he leaves no doubt about it. “Number the players,” Morse almost yells at us. “Catcher 2, pitcher 1; basemen 3, 4, 5; shortstop 6. . . .” The New York Giants themselves had reintroduced scorekeeping suggestions by 1915, and conformed to the method demanded by Morse, as if it had always been that way.

We can actually narrow the time frame of the change to a window beginning not in 1891, but closer to 1896. In the same pile of amazingly simple artifacts as that Giants scorecard is the actual softcover scorebook used by Charles H. Zuber, the Reds’ beat reporter for the Cincinnati Times-Star five years later. Zuber employed a “Spalding’s New Official Pocket Score Book” as he and the Reds trudged around the National League in the months before the election of President McKinley. Inside its front cover, one of the Great Spalding’s many minions has provided intricately detailed scoring instructions. “The general run of spectators who do not care to record the game as fully as here provided,” he writes with just a touch of condescension, “can easily simplify it by adopting only the symbols they need.”

That this generous license was already being taken for granted is underscored by the fact that the Spalding editor suggests “S” for a strikeout, but writer Zuber ignores him completely and employs the comfortingly familiar “K.” But the book’s instructions are not entirely passé. They include the suggestion that the scorer use one horizontal line for a single, two for a double, etc. — which is exactly the way I was taught to do it, in the cavernous emptiness of Yankee Stadium in 1967.

The Spalding instructions go on for 11 paragraphs, and the official rules for scoring fill another 20. But remarkably, there are is no guidance about how to numerically abbreviate the shortstop, third baseman, or anybody else who happened to be on the field. There isn’t even the suggestion that a scorer must number the players, or abbreviate the players, according to their defensive positions: “Number each player either according to his fielding position or his batting order, as suits, and remember that these numbers stand for the players right through in the abbreviations.”

In other words — use any system you damn well please. Number the shortstop “5” if you want, or “6.” Or, if he’s batting leadoff, use “1.” Or if he’s exactly six feet tall, try “72.”

If by now you have wondered if the father of scorekeeping and statistics, Henry Chadwick, was not sitting there with smoke pouring from his ears over all this imprecision and laissez-faire, don’t worry — he was. As early as his 1867 opus The Game Of Base Ball he was an advocate of one system and one system only — numbering the players based on where they hit in the order.

I realize that some of the most ardent of you, who have little shrines to Chadwick (in your minds, at least) as the ancient inspiration for SABR itself, must be reeling at the thought. Even if you think using “6” for the third baseman instead of the shortstop is a bit silly, it’s a lot better than Chadwick’s idea, surely the worst imaginable system of keeping score, based on the batting lineup (“groundout to short, 1 to 7 if you’re scoring at home — no, check that, I forgot, the relief pitcher Schmoll took Robles’ spot in the batting order in the double switch, so score it 9 to 7”).

Before we knock down the Chadwick statue outside SABR headquarters, this caveat is offered in his defense. In 1867, random substitutions were not permitted at all, and not until 1889 did they become even partially legal. Within a game, the batting order changed about as frequently as the designated hitter today assumes a defensive position. Chadwick’s insistence on defensive numbering based on offensive positioning still doesn’t make sense on a game-to-game basis, but at least he wasn’t completely nuts.

But, as Peter Morris points out, Chadwick wanted to keep his system even as the substitution rule was changing. That same series of “Hints On Scoring” from the 1891 Giants scorecard first appeared, word for word, in a column in the New York Mail and Express in early 1889.

Weeks later, Chadwick is railing against it in the columns of Sporting Life. This new defensive-based scoring system is, he writes, “in no respect an improvement on the plan which has been in vogue since the National League was organized. If you name the players by their positions, and these happen to be changed in a game, then you are all in a fog on how to change them.”

Chadwick was wrong about the ramifications but right about the coming fog.

Certainly, as the Giants scorecard and Charles Zuber’s Spalding scorebook suggest, confusion would reign through the 1890s and into the new century. The New York scorecards soon reverted to “3B” and “SS” and dropped all hinting on what the bearer was supposed to do. Zuber’s scoring system starts with the first baseman at “1,” has the shortstop as “4,” and the pitcher and catcher as “5” and “6.” Only the Hall of Fame manager Harry Wright seems to have nailed it. In the voluminous scorebooks he kept through to his death in 1893, he has penciled in, in perfect, tiny lettering, the third baseman as “5” and the shortstop as “6.”

So how was this chaos resolved?

This proves to have been the unexpected topic of conversation in the late 1950s between a budding New York sportswriter and one of the veterans of the business. Bill Shannon, now one of the three regular official scorers at Yankee and Shea Stadiums, was talking scorekeeping with Hugh Bradley.1 Bradley had been covering baseball in New York since the first World War, had been sports editor of the New York Post in the ‘30s, and was at the time of his conversation with Shannon a columnist with the New York Journal-American.

Shannon recalls that, out of nowhere, Bradley began talking about a great ancient conflict between rival camps of scorers, one of which favored the shortstop as “5” and the other as “6.” The inevitable clash occurred, Bradley told him, at the first game of the first modern World’s Series.

The World’s Series, of course, had gone out with a whimper and not a bang in 1890. Though the Brooklyn Bridegrooms and Louisville Cyclones had been tied at three wins apiece, disinterest in that war-ravaged season was so profound that attendance at the last three games had been 1,000, 600, and 300, respectively. They didn’t even bother to play the decisive game.

Thus when the series was restored 13 years later, every attempt was made to keep haphazardness and informality out of the proceedings. Not just one official scorer was required, but two — and the two foremost baseball media stars of the time: Francis C. Richter of Philadelphia, the publisher and editor of Sporting Life, and Joseph Flanner of St. Louis, editor of The Sporting News.

Hugh Bradley could not have witnessed it, but he could have heard it second- or third-hand. As the rivals from the two publications filled out their scorecards, somewhere in the teeming confusion of the Huntington Avenue Grounds in Boston, somebody — probably the more volatile Flanner — peeked.

And he didn’t like what he saw.

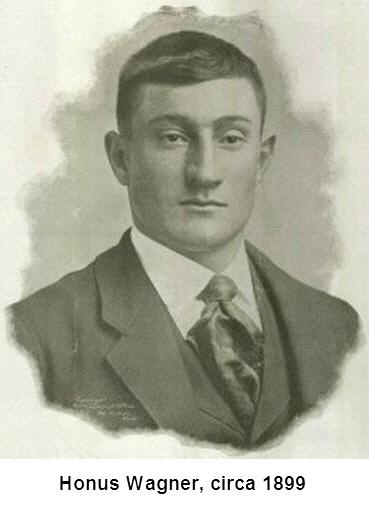

Richter was numbering Pittsburgh shortstop Honus Wagner as “5” and third baseman Tommy Leach as “6.”

Questioned by Flanner, Richter supposedly responded that that was the way they kept score where he came from, and why would anybody do it any differently?

The basis of their argument was supposed to have been regional. The shortstop, Bradley told Shannon, was still a comparatively new innovation in the game, and it really defined two different positions. In Flanner’s Midwest, he was positioned much like the softball short-fielders, not truly an infielder and thus not meriting an interruption of the natural numbering of the basemen. In Richter’s East, the shortstop had developed into what he is today — the second baseman’s twin. So what if he didn’t anchor a bag? It was second baseman “4,” shortstop “5,” third baseman “6” and don’t they have any good eye doctors out there in St. Louis, friend Flanner?

Bradley’s recounting of the conflict had voices being raised and dark oaths being sworn before the more malleable Richter gave way, little knowing that he was ceding the issue forever on behalf of generations to come who saw the same logical flaw he had seen.

Bill Shannon’s authority on such matters is near absolute. He can not only recount virtually every game he’s ever seen, but can also run down the personnel histories of the sports departments at the dearly departed of New York’s newspapers. He believes in the long-gone Bradley’s saga of near-fisticuffs between Richter and Flanner — while ‘Nuf Sed McGreevey and his Royal Rooters worked themselves into a frenzy before the first pitch of the 1903 Series — because of its likely provenance.

One of Bradley’s writers when he was sports editor of the Post in the ‘30s was Fred Lieb, himself almost antediluvian enough to have witnessed the Flanner-Richter showdown. Shannon suspects Bradley got the story from Lieb, and that Lieb had gotten it from his fellow Philadelphian Francis Richter.

For now, that’s all we’ve got — a pretty good-sounding anecdote. There is nothing yet found in the files of The Sporting News, New York Times, Washington Post, or even in any of the contemporary Spalding or Reach annual guides. No Flanner-Richter screaming match, no ruling on whether the shortstop or the third baseman was “5,” no verified explanation as to how we got from the hints in the 1891 Giants scorecard to the instructions of the 1909 World Series program, no smoking gun proving when it became this way, as if there had never been any other way.

Needless to say, further research is encouraged and its results solicited.

In the meantime, dare I even mention that the 1891 Giants book also identifies the right fielder as “7” and the left fielder as “9”?

KEITH OLBERMANN anchors MSNBC’s nightly newscast, Countdown, and co-hosts a dally hour with Dan Patrick on ESPN Radio. A SABR member since 1984, he still regrets not acting on his intention to sign up during a visit lo Cooperstown in 1973.

Notes

1 Bill Shannon died in 2010, after this article was initially published.