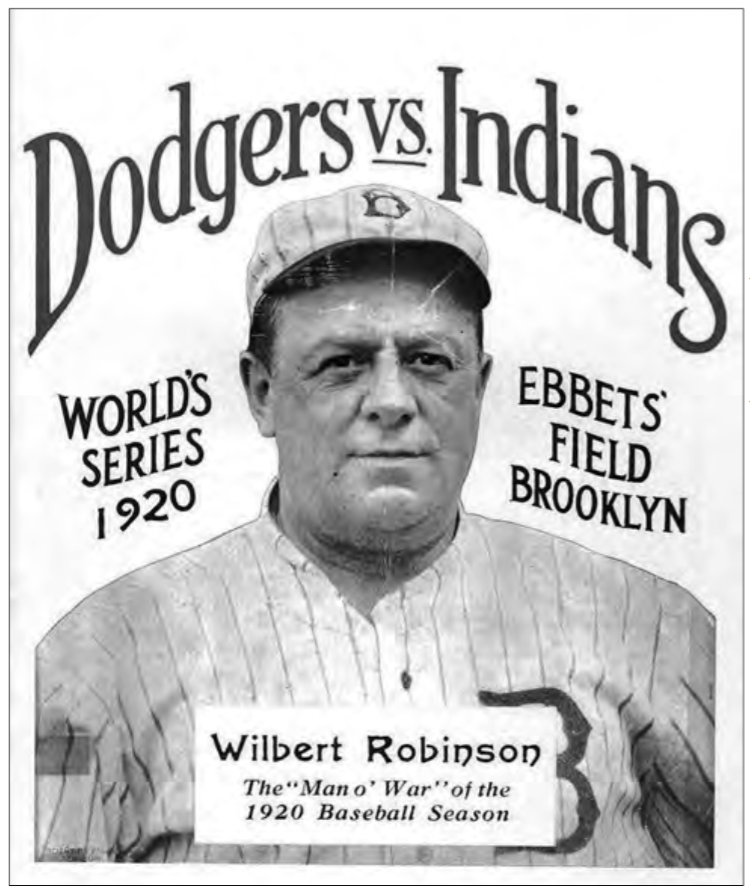

Wilbert Robinson and the 1920 Brooklyn Robins

This article was written by Gordon J. Gattie

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Big Apple (New York, 2017)

The Brooklyn Robins reached the World Series for the third time as a National League franchise, under manager Wilbert “Uncle Robbie” Robinson during the 1920 season. Brooklyn’s first National League championship occurred in 1890, when they finished first in the NL with an 85–44 record; they tied the American Association champion Louisville Colonels in the 1890 World Series 3–3–1. The team celebrated its second NL championship in 1916, but lost the World Series to the Boston Red Sox in five games.

The 1920 Robins were led by future Hall-of-Fame pitcher Burleigh Grimes, Hall-of-Fame outfielder Zach Wheat, star pitcher Leon Cadore, and solid third baseman Jimmy Johnston. The Robins started strong by winning eight of their first 11 games and never dropping more than four games from the National League lead throughout the season. On September 9, Brooklyn defeated St. Louis to secure sole possession of first place, and clinched their fifth National League pennant on September 27 after their crosstown rival New York Giants lost to the Boston Braves.1 Brooklyn completed the regular season with a 93–61 record, finishing seven games ahead of the Giants. The Robins ultimately lost to the Cleveland Indians, 5–2, in a best-of-nine series that featured two notable firsts in World Series history—both accomplished by Cleveland players during the momentum-shifting Game 5: a grand slam and an unassisted triple play.2

As such, the 1920 Robins may be remembered more by the Indians’ achievements and events on the national stage rather than their own successes and failures. The 1920 season marked the introduction of the liveball era and the only fatality occurring during game play, and the Black Sox scandal cast a shadow during the World Series.3,4 In Brooklyn, Uncle Robbie’s ballclub overcame an unsettled infield, a stretch of 58 innings covering three games in early May when the club went 0–2–1, the loss of outfielder Tommy Griffith, and a late June swoon, by playing .800 baseball during September to earn the pennant. The team overcame preseason prognosticators and challenges throughout the year; following the regular season, Uncle Robbie quipped, “No special system of playing won the 1920 pennant for the Brooklyn Superbas.”5

Like all major league clubs, the Robins were severely impacted by World War I. Although they made their third World Series appearance in 1916, four years later the only regulars playing in the same positions included shortstop Ivy Olson and left fielder Zach Wheat. During that span, Johnston moved from the outfield to infield and the other players no longer played for Brooklyn. The pitching staff had changed too, with Grimes and Cadore complementing Jeff Pfeffer and Rube Marquard. Staff ace Burleigh Grimes topped 20 wins and 300 innings for the first time in his career, Zach Wheat finished fourth in the NL with a .328 batting average, and outfielder Hi Myers paced the National League in triples for the second straight season.

Twenty-one Robins appeared in at least 20 games during the 1920 season; nine were purchased outright from other ballclubs, four joined via the Rule 5 Draft, four were acquired via trade, and four were selected off waivers. The top four players appearing in the most games that season—Johnston, Myers, Wheat, and Olson—had also played in the 1916 World Series against the Boston Red Sox. Catcher Otto Miller was the only other non-pitcher acquired before 1916. Table 1 describes how the Robins’ roster was compiled for all players who appeared in more than 20 games for the team during the 1920 season. Brooklyn owner Charles Ebbets wanted his team set entering the 1920 season; a month before training camp started, Ebbets had signed 27 of 28 ballplayers by mid-February. The lone holdout was Tommy Griffith, who was debating retirement from professional baseball.6

Table 1. 1920 Robins’ team assemblage

| Player | Position | 1920 GP | Year Acquired | How Acquired |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jimmy Johnston | 3b | 155 | 1915 | Purchase |

| Hi Myers | of | 154 | 1909 | Purchase |

| Zach Wheat | of | 148 | 1909 | Purchase |

| Ivy Olson | ss | 143 | 1915 | Waivers |

| Pete Kilduff | 2b | 141 | 1919 | Trade |

| Ed Konetchy | 1b | 131 | 1919 | Purchase |

| Bernie Neis | of | 95 | 1919 | Purchase |

| Tommy Griffith | of | 93 | 1919 | Trade |

| Otto Miller | c | 90 | 1909 | Rule 5 Draft |

| Clarence Mitchell | p | 55 | 1917 | Waivers |

| Ernie Krueger | c | 52 | 1917 | Waivers |

| Burleigh Grimes | p | 43 | 1918 | Trade |

| Rowdy Elliott | c | 41 | 1919 | Purchase |

| Bill McCabe | util | 41 | 1920 | Purchase |

| Al Mamaux | p | 41 | 1918 | Trade |

| Leon Cadore | p | 35 | 1914 | Rule 5 Draft |

| Sherry Smith | p | 33 | 1914 | Rule 5 Draft |

| Jeff Pfeffer | p | 30 | 1913 | Purchase |

| Ray Schmandt | 1b | 28 | 1917 | Rule 5 Draft |

| Rube Marquard | p | 28 | 1915 | Waivers |

| Bill Lamar | of | 24 | 1920 | Purchase |

The 1920 Brooklyn Robins opened their season with a 9–2 victory over the Philadelphia Phillies on April 14 at Ebbets Field during unseasonably cold weather. Both pitchers went the distance, with Cadore allowing two runs on eight hits while striking out two hitters and walking none, and Philadelphia starter Eppa Rixey allowing nine runs (five earned) on nine hits with four walks and no strikeouts. According to The New York Times, the game was more lost by the Phillies than won by the Robins: “Weak pitching in the pinches, uncertainty in fielding and a generally poor performance made the Phillies appear even worse than the preliminary dope on the team had promised.”7 Konetchy was the offensive star, registering two singles and three RBIs. Hitting third in the Phillies lineup that afternoon was right fielder Casey Stengel, who famously guided the Dodgers 1934–36 during the first stop in his 25-year major league managerial career.

The Robins continued to play solid ball throughout April, although the infield struggled during the season’s first month. The initial team report printed in The Sporting News concluded, “The new Brooklyn infield is showing rather more brains than skill as yet. It was responsible for the seven mechanical errors in the two games with the Phillies, but it made no mental mistakes.”8 Brooklyn finished the month with an 8–4 record, a half-game behind Cincinnati. The Robins were second in runs scored, and allowed the third fewest runs in the league, only six fewer than the Boston Braves, who had played only nine games through April 30. The team was pointed in the right direction.

The first weekend in May proved to be an extremely long one for the Robins, first playing the Boston Braves in Boston, then back to Brooklyn for a game against the Phillies, followed by a return to Boston before taking on their crosstown rival Giants in a three-game series at the Polo Grounds. The estimated 4,500 fans who attended the Saturday, May 1 game between Brooklyn and Boston were treated to a marathon pitching duel that lasted for 3 hours and 50 minutes—26 innings.

Leon Cadore, the Robins’ starting pitcher, had started the season strong. After his complete game win against Philadelphia, he fired an 11-inning, 7-hit shutout against the Braves, then allowed two earned runs over six innings in a loss against New York, bringing a 2–1, 1.38 ERA into the contest. His mound opponent, Joe Oeschger, also pitched three games in April: a 6-hit shutout against the Giants, a tough-luck 1–0 loss against Brooklyn where the lone run was scored in the bottom of the 11th inning, and a third consecutive complete game win against the Phillies when he allowed a lone earned run and two unearned runs, to increase his ERA to 0.63. These two hurlers pitched the entire 26-inning game, with Brooklyn scoring in the fifth inning when Olson singled home Krueger. Boston responded with their only run during the following frame when Tony Boeckel singled home Walton Cruise after Cruise tripled to left-center field. Cadore allowed 15 hits and five walks while striking out seven hitters and Oeschger allowed nine hits—all singles—and struck out seven with four walks before the game was called because of darkness.9 Interestingly, as the game progressed through the extra innings, the two sportswriters covering the game—Eddie Murphy from The New York Sun and Thomas Rice of The Brooklyn Eagle—were receiving story requests from other area newspapers; they were also exhausted by night’s end.10 The previous record for longest game occurred when the Boston Americans lost to the Philadelphia Athletics, 4–1, in 24 innings on September 1, 1906.

The Robins returned to Ebbets Field the following day, hosting the Phillies, with Philadelphia starter George Smith facing Brooklyn ace Grimes. The Phillies struck first in the third inning as Bevo LeBourveau crossed the plate on a Dave Bancroft double. Philadelphia padded their lead on a two-run LeBourveau homer. The Robins responded with two runs later that inning: Neis scored when Myers doubled and reached third on a dropped ball; subsequently, Konetchy plated Myers. In the bottom of the ninth, Wheat tied the game when he blasted a 3–1 pitch over the right field wall. The teams remained scoreless until the 13th inning when Bancroft scored on a sacrifice fly after Stengel was walked to load the bases, giving the Phillies a 4–3 win. Once again, both pitchers went the distance, and now Brooklyn established a record of playing 39 innings in two games on successive days.11

The next day, Brooklyn appeared in Boston with Sherry Smith taking on Braves’ starter Dana Fillingim, who brought an 0–2 record and 0.00 ERA into the Monday afternoon contest. Fillingim pitched 17 innings over two starts but all his runs allowed were unearned. The Robins scored first when Johnston reached on a fielder’s choice but Smith came home on an error during the fifth inning; Olson also attempted to score on the play but was thrown out at home. The Braves tied the game in the sixth inning as Walter Holke’s sacrifice fly brought in Charlie Pick. The game remained tied for the next 11 innings when manager Robinson asked the game to be called on account of darkness; his request was denied. Two innings later, John Sullivan scored the winning run on a Boeckel single and Boston won, 2–1. Both starting pitchers threw complete games; Fillingim earned his first victory and now carried a 0.00 ERA over 36 innings into his next start. After playing 58 innings in three consecutive days—or six full nine-inning games with four additional innings—during which they went 0–2–1, the Robins fell into third place. The New York Times opened the game report, “Rumors were circulating around Braves Field late tonight the members of the Braves and Dodgers baseball clubs were about to assemble in mass meeting in Faneuil Hall and declare themselves on this business of working overtime.”12

In addition to their marathon extra-inning games to begin the month, Brooklyn proceeded to play five more extra-inning games during May, including three of the six subsequent games. The Robins still finished the month with a 13–10 record; with an overall 21–14 record, they were a half-game behind the Chicago Cubs and percentage points ahead of Cincinnati. Although their offense sputtered during the month, their strong pitching and fielding kept them competitive. During the month, the Robins strengthened their bench by purchasing utility player Bill McCabe from Chicago and selecting outfielder Wally Hood off waivers from Pittsburgh. In addition, Tommy Griffith returned to the diamond after threatening retirement from baseball. During the preceding offseason, Griffith profited from working as a stock salesman, and was still upset over his trade from the Cincinnati ballclub the year before. Once Griffith was assured his salesman career would not suffer from playing ball, he returned to the Robins.13

In addition to their marathon extra-inning games to begin the month, Brooklyn proceeded to play five more extra-inning games during May, including three of the six subsequent games. The Robins still finished the month with a 13–10 record; with an overall 21–14 record, they were a half-game behind the Chicago Cubs and percentage points ahead of Cincinnati. Although their offense sputtered during the month, their strong pitching and fielding kept them competitive. During the month, the Robins strengthened their bench by purchasing utility player Bill McCabe from Chicago and selecting outfielder Wally Hood off waivers from Pittsburgh. In addition, Tommy Griffith returned to the diamond after threatening retirement from baseball. During the preceding offseason, Griffith profited from working as a stock salesman, and was still upset over his trade from the Cincinnati ballclub the year before. Once Griffith was assured his salesman career would not suffer from playing ball, he returned to the Robins.13

During the first week in June, the Robins reeled off a four-game winning streak, which included a 7-hit shutout by Pfeffer and a 6-hitter by Grimes, to take over first place. However, their success was short-lived; after the streak, Brooklyn lost nine of their next 11 ballgames. After a late-inning rally fell short, resulting in a 9–7 loss to Pittsburgh on June 22, the Robins extended their losing streak to four games and dropped into third place.14 The papers called out their poor play: “Such baseball as was produced would have shamed a respectable sand-lots team.”15 Brooklyn was now only a half-game in front of surging St. Louis. The Cardinals were in the midst of their own five-game skid, but had won 13 of 14 starting June 1 to jump from sixth to third place. The Robins rebounded with a three-game winning streak following their loss to Pittsburgh, but their inconsistency resulted in a following six-game losing streak, which included losing five games to the struggling Braves. Although the Brooklyn offense was showing signs of life, they couldn’t capitalize on opportunities and the pitching was ineffective.16

Brooklyn’s fortunes improved over the summer, as their 23–12 July record and 14–13 August record moved them back into contention with Cincinnati and New York. Although the Robins suffered a four-game losing streak in the final week of August, they captured back those games with an equivalent four-game winning streak that included back-to-back shutouts by Grimes and Cadore. The Robins were swept by Philadelphia in a Labor Day doubleheader, and promptly returned the favor the following day, initiating a 10-game winning streak which culminated with a doubleheader sweep of the Cubs on September 13.17 Their sweep resulted in a five-game lead over both Cincinnati and New York and commanding control in the pennant race. Cadore delivered back-to-back shutouts during the streak, and the team’s overall offensive production was increasing. John McGraw’s Giants were coming on strong with a 20–11 August record, but it wasn’t enough to catch the cruising Robins, while Pat Moran’s Cincinnati Reds played .511 ball from July 1 onwards. Finally, on September 27, Brooklyn won the pennant after the Braves dramatically ended the Giants’ World Series hopes on a Boeckel ninth-inning clout during the second game of a doubleheader.18

Hall-of-Famer Zach Wheat enjoyed another great season at the plate. He led the Robins with personal career highs in runs (89), hits (191), and slugging percentage (.463), and also led in batting average (.328), OPS (.848), and home runs (9); he finished second in doubles (26), triples (13), and RBIs (73). He still remains the Dodgers’ all-time franchise leader in hits, doubles, triples, and total bases.19

Although the Robins lost their fourth attempt at securing a world championship, two lesser known events occurred that October: a curse created by a slighted mascot, and brothers who faced each other for the first time in World Series history.

The 1920 Robins were arguably victimized by one of the earliest curses in the twentieth century, when Brooklyn’s mascot Eddie Bennett was prevented from joining the Robins for the four games scheduled in Cleveland following Game 4. Although Bennett had served as a good-luck charm for the Robins during the season and during the previous year with the American League pennant-winning Chicago White Sox, his disappointment over not traveling with the team led to his supposedly “placing a curse” on his hometown Robins.20 Bennett joined the Yankees the following season, and for twelve years served as a batboy/mascot for four World Series winners.21 The curse tale gained notoriety during the next decade; while the Yankees enjoyed success, the Robins wouldn’t return to the World Series for another 21 years.

Secondly, brothers faced each other for the first time during the 1920 World Series. Doc and Jimmy Johnston were born just over two years apart in Cleveland, Tennessee. Doc, whose given name was Wheeler Roger Johnston, tended first base for the Indians while his younger brother Jimmy, or James Harle Johnston, covered third base for the Robins. The brothers enjoyed similar careers; Doc played 1056 games, compiling a .263 career batting average with 14 home runs and 381 RBIs and Jimmy played 1377 games, compiling a .294 career batting average with 22 homers and 410 RBIs. In 1920 their batting averages were extremely close—Doc hit .292 over 535 at-bats while Jimmy delivered a .291 average over 635 at-bats: “Wheeler has it on Jimmy in the Frequency (sic) and weight of his hits, but Jimmy has it on Brother Wheeler in stealing and sacrificing.”22

Doc debuted in 1909 with the Cincinnati Reds, playing three games while going hitless in ten at-bats. According to his younger brother, Doc received his nickname from his father, “who used to say that he would grow up some time to be a Doctor.”23 The following three years he played in the minors, with the Chattanooga Lookouts (1910), Buffalo Bisons (1910), and New Orleans Pelicans (1911–12), before returning to the majors with Cleveland for 43 games toward the end of the 1912 season. Three years later he was purchased by the Pirates; during the following season, Pittsburgh sent Doc to the Birmingham Barons—as one of the players to be named later for a young spitball pitcher named Burleigh Grimes, whom he also faced during the 1920 series. Grimes reached the majors during the 1916 season with Pittsburgh before the Pirates traded him, pitcher Al Mamaux, and infielder Chuck Ward to the Robins for second baseman George Cutshaw and outfielder Casey Stengel in January 1918.24

Jimmy played a single game with the Chicago White Sox in 1911; he was selected by the Chicago Cubs in the 1913 Rule 5 draft, appearing in 50 games with the Cubs the following year. He joined Brooklyn in 1916, and played with the Robins until the 1926 season. Jimmy played all the infield and outfield positions during his early years before Brooklyn manager Wilbert Robinson settled on him playing third base, a position with a revolving door in the preceding years: “Here Johnston has played a resolute, active game, which has given abundant satisfaction to the public accustomed as it was to seeing a new performer at third base about three times a week.”25 In 1920 and 1921 Johnston played 146 and 150 games at third base, respectively, the steadiest assignment he held throughout his 13-year career.

Both brothers attained career highs in games played that season (Doc 147, Jimmy 155), with Jimmy tying for the National League lead with New York’s Highpockets Kelly and St. Louis’s Milt Stock. Doc also reached career highs for his 11-year career in hits (156), doubles (24), and RBIs (71). Jimmy posted solid numbers, leading the Robins in plate appearances (707), stolen bases (19), and finishing second to teammate Zach Wheat in runs (87) and hits (185). Jimmy posted career highs in batting average, doubles, triples, home runs, and stolen bases the following season. Although Jimmy had the lower regular season batting average, Doc held a slight edge during the 1920 Series—going 3-for-11 and scoring once in five games compared with Jimmy’s 3-for-14, two-run performance covering four games. Doc’s lone run scored came on Cleveland pitcher Jim Bagby’s home run during the notable game five. Both brothers retired to farms following their playing careers, and both passed away in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

The 1920 Brooklyn Robins were more than just the Indians’ opponent during the Series; Uncle Robbie led the team through a challenging season of peaks and valleys, a three-way season-long pennant chase with the New York Giants and Cincinnati Reds, and unique performances from key players.

GORDON J. GATTIE serves as a human-systems integration engineer for the U.S. Navy. His baseball research interests involve ballparks, historical records, and statistical analysis. A SABR member since 1998, Gordon earned his Ph.D. from SUNY Buffalo, where he used baseball to investigate judgment/decision-making performance in complex dynamic environments. Originally from Buffalo, Gordon learned early the hardships associated with rooting for Buffalo sports teams. Ever the optimist, he also cheers for the Cleveland Indians and Washington Nationals. Lisa, his lovely bride who also enjoys baseball, continues to challenge him by supporting the Yankees. Gordon has contributed to multiple SABR publications.

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES

Baseball Reference: http://www.baseball-reference.com

Blanpied, Ralph B. (2005). Brooklyn v. Boston in 26 Innings. In Andrew Paul Mele (Ed.) A Brooklyn Dodgers Reader. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

Golenbeck, Peter. (2000). Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Chicago, IL: Contemporary Books.

James, Bill. (1997). The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers from 1870 to Today. New York: Scribner.

Retrosheet: http://www.retrosheet.org/

Simon, Tom. (2004). Deadball Stars of the National League. Cleveland, OH: Society for American Baseball Research.

Thorn, John; Palmer, Pete; Gershman, Michael; and Pietrusza (2004). Total Baseball: The Official Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball. New York: Viking Press.

NOTES

1 Daniel, “Fifth National League Pennant for Brooklyn,” The Sun and New York Herald, September 28, 1920: 14.

2 Joseph Wancho, “October 10, 1920: A game of World Series firsts: unassisted triple play and grand slam,” SABR Baseball Games Project. Accessed 04 December 2016 at http://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/october-10-1920-world-series-game-firsts-unassisted-triple-play-and-grand-slam.

3 Associated Press, “Ray Chapman Dies of Blow by Ball; Mays Exonerated,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 17, 1920: 1.

4 Associated Press, “Indict Two Gamblers in Baseball Plot; Men Named by Williams in Confession; Inquiry Here to Guard the 1920 Series,” The New York Times, September 30, 1920: 1–2.

5 Thomas S. Rice, “Nerve and Spirit Won Pennant, Says Robinson,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 30, 1920: 1.

6 Thomas S. Rice, “All Dodgers Signed Early in February,” The Sporting News, March 4, 1920: 2.

7 “Giants and Yankees Lose But Robins Win in Opening Game of Major League Season: Dodgers Open With Easy Victory,” The New York Times, April 15, 1920: 15.

8 Thomas S. Rice, “Dodgers Please By Display of a Punch,” The Sporting News, April 22, 1920: 3.

9 “Brooklyn Ties in Record Game of 26 Innings,” The Sun and New York Herald, May 2, 1920: 1.

10 Frank Graham Jr., Brooklyn Dodgers: An Informal History (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2002): 78.

11 “Ruth’s Home Run Liner Enables Yankees to Defeat the Red Sox, 7 to 1—Dodgers Succumb to Phillies by 4 to 3: Dodgers Go 13 Innings to Defeat,” The Sun and New York Herald, May 3, 1920: 9.

12 “Yankees and Giants Lose in Nine Innings, Brooklyn in Nineteen,” The New York Times, May 4, 1920: 12.

13 Nelson “Chip” Greene, “Tommy Griffith”, SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/00873ae1.

14 “Dodgers Continue to Slip: Brooklynites Drop Fourth Straight Game, Losing to Pirates,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, NY), June 23, 1920: 26.

15 “Late Rally Fails to Save Dodgers,” The New York Times, June 23, 1920: 12.

16 “Yankees Score 3 Runs in Ninth, Beating Red Sox by 6 to 5—Giants Win From Phillies by 7 to 1—Dodgers Lose: Cadore Ineffective Against the Braves,” The Sun and New York Herald, June 30, 1920: 13.

17 “Giants Win and Dodgers Take Two Games While Reds Lose—Ruth’s 49th Homer Enables Yankees to Beat Tigers: Dodgers Twice Rout Cubs, Increasing Lead in Race,” The Sun and New York Herald, September 14, 1920: 10.

18 Thomas S. Rice, “Brooklyn Wins Pennant—World Series Opens in West,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 28, 1920: 20.

19 Eric Enders, “Zack Wheat,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/c914f820.

20 Jack Kavanagh and Norman Macht, Uncle Robbie (Phoenix, AZ: Society for American Baseball Research, 1999): 126.

21 Peter Morris, “Eddie Bennett” In Jacob Pomrenke (Ed.) Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox (Phoenix, AZ: Society for American Baseball Research, Inc., 2015): 265–68.

22 Thomas S. Rice, “Others Have Beaten Indians Sluggers—Why Not Superbas?,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 4, 1920: 2.

23 F.C. Lane, “When Brothers Meet in a World’s Series: How the Two Johnston’s (sic) of Cleveland and Brooklyn Hope to Clash for a World’s Championship,” Baseball Magazine, November 1920: Volume 25, Issue 6, 578.

24 Charles F. Faber, “Burleigh Grimes,” SABR Biography Project, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/0957655a.

25 F.C. Lane, “When Brothers Meet in a World’s Series: How the Two Johnston’s of Cleveland and Brooklyn Hope to Clash for a World’s Championship,” Baseball Magazine, November 1920: Volume 25, Issue 6, 578.