Will sabermetrics tilt the scale on Deadball Era players entering the Hall of Fame?

This article was written by John McMurray

This article was published in SABR Deadball Era newsletter articles

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in the SABR Deadball Era Research Committee’s “The Inside Game” newsletter for November 2014.

With Hank O’Day and Jacob Ruppert being inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2013, it is reasonable to ask which Deadball Era figures — if any — still merit inclusion. Considering that no current voters would have seen any of the candidates from that era play, advanced metrics may tilt the scale when it comes to making the case for long-ago players.

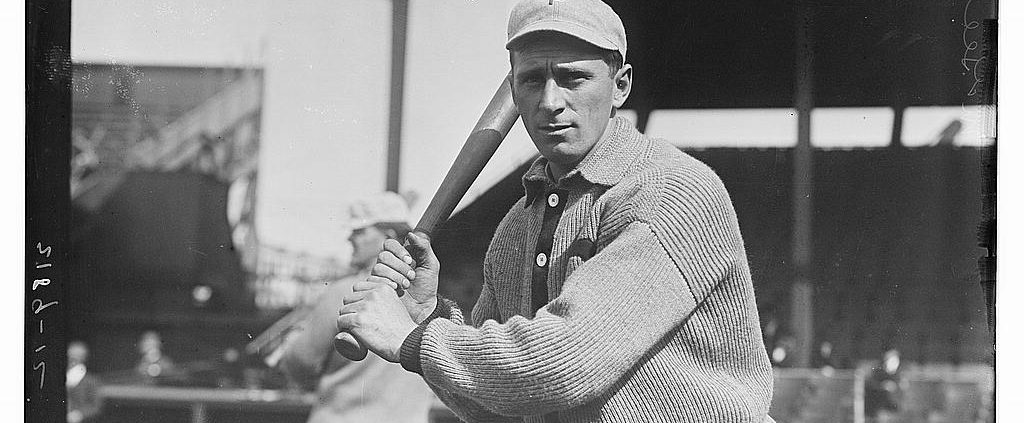

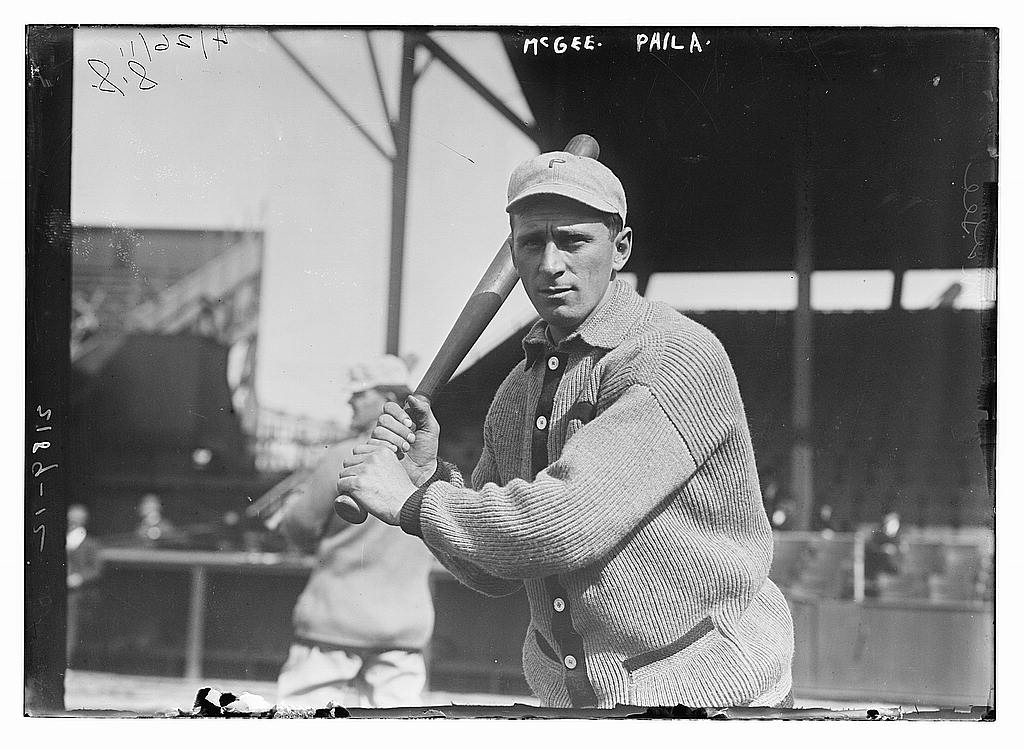

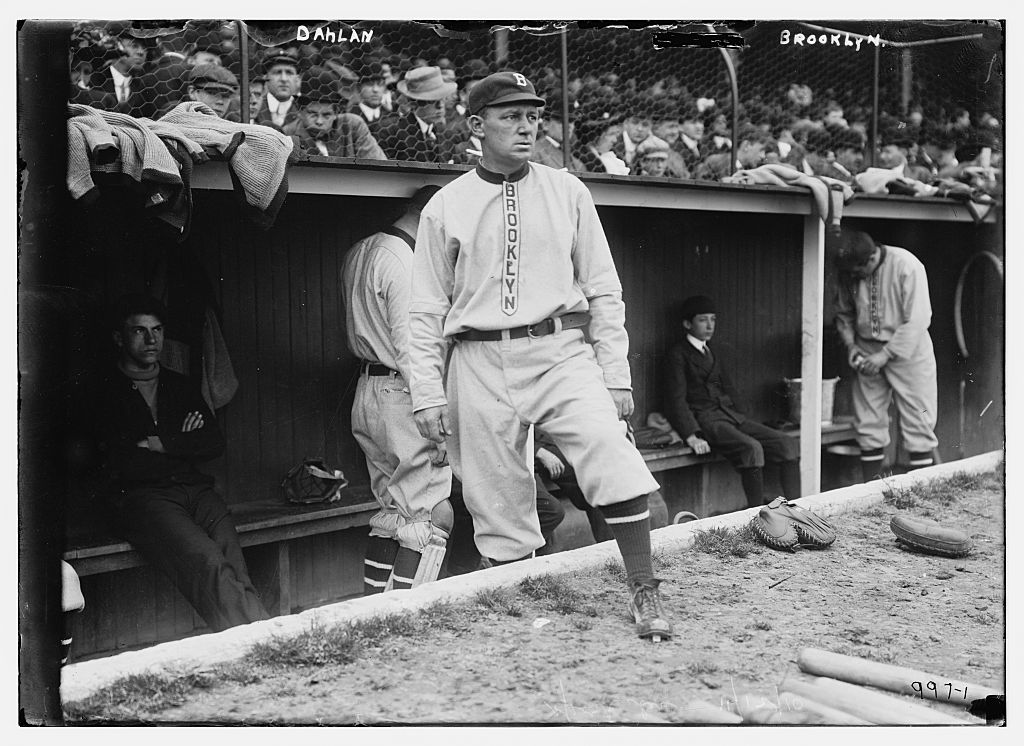

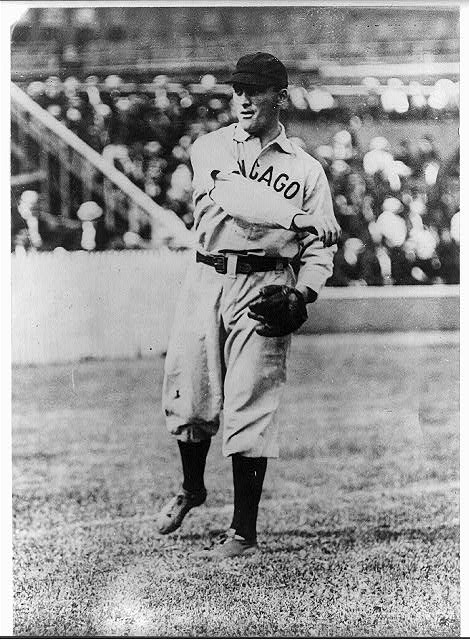

There are a surprising number of Deadball Era players whose candidacies still inspire Hall of Fame debate. The most consistently mentioned possibilities are Bill Dahlen, Chicago and Brooklyn’s renowned (and tempestuous) shortstop; Sherry Magee, recognized for his offensive prowess with Philadelphia from 1904 through 1914; and outfielder Jimmy Sheckard, who is best known for his time with the Cubs.

There are a surprising number of Deadball Era players whose candidacies still inspire Hall of Fame debate. The most consistently mentioned possibilities are Bill Dahlen, Chicago and Brooklyn’s renowned (and tempestuous) shortstop; Sherry Magee, recognized for his offensive prowess with Philadelphia from 1904 through 1914; and outfielder Jimmy Sheckard, who is best known for his time with the Cubs.

Peter Morris is the author of several baseball books relating to baseball’s formative years and a member of the Hall of Fame’s 16-member committee in 2012 which was charged with selecting players for the Hall of Fame who played prior to 1947. He believes that players elected to the Hall of Fame must deserve the honor legitimately:

“My philosophy is that we should be putting people in if they really, clearly belong in,” Morris said. “If instead the narrative is ‘Well, this guy is the best guy not in the Hall of Fame,’ that’s not a good reason at all to put somebody else in. So I think it’s very important to avoid, ‘Let’s find the most qualified guy who hasn’t gotten in so far,’ and just keep electing players until the Hall of Fame is cluttered with guys who are marginal candidates, or even worse. That would be the worst thing you could possibly do.”

A further consideration is that the Deadball Era players who have not been elected were voted upon many times by people who actually saw them play and still were not chosen. That stands in contrast to many 19th-century stars, most of whose contemporaries were deceased when the first group of Hall of Famers was elected in 1936.

Bill Deane, former Senior Research Associate at the National Baseball Library, author of Baseball Myths, and recognized authority on the Hall of Fame voting process offers this perspective:

“One could make a valid case that there’s not much point in going back and looking at Deadball Era candidates any longer, and instead to focus on the 19th-century players, since there were not too many people alive who had actually seen them play when the elections started, as well as Negro League players, who weren’t even eligible until 1971. So it’s probably more challenging for Deadball Era players to get elected at this point, especially considering that their contemporaries didn’t vote them in.”

Whereas Deacon White, a star from the 19th century who was inducted in 2013, appears to have been a glaring omission from the Hall of Fame, none of the remaining Deadball Era players has as clear cut of a case.

Sherry Magee is a representative example. Magee, who is described in his SABR BioProject biography written by Tom Simon as a “five-tool player” and as the Phillies’ “greatest offensive star,” is credited with having the most RBIs in the National League in four different seasons (although RBI was not recorded as an official statistic until 1920). His Hall of Fame candidacy, however, has been hindered by other factors.

“There are two things that stand out on a negative side of Magee’s candidacy,” said Simon, editor of Deadball Stars of the National League and a member of the same 2012 Hall of Fame Pre-Integration Committee which included Peter Morris. “Magee was a very good player for a pretty long time, but he never played on a championship team until he was with Cincinnati in 1919, when he was a part-timer. So he was never an important part of a pennant-winning team. In fact, it was only after he was traded that the Phillies ended up making it to the World Series in 1915.

“There are two things that stand out on a negative side of Magee’s candidacy,” said Simon, editor of Deadball Stars of the National League and a member of the same 2012 Hall of Fame Pre-Integration Committee which included Peter Morris. “Magee was a very good player for a pretty long time, but he never played on a championship team until he was with Cincinnati in 1919, when he was a part-timer. So he was never an important part of a pennant-winning team. In fact, it was only after he was traded that the Phillies ended up making it to the World Series in 1915.

“Number two, Magee had that terrible incident with the umpire (a confrontation with Bill Finneran in 1911), which actually reminds me a little of the Roberto Alomar situation. I don’t think that one bad incident should necessarily prevent him from getting in to the Hall of Fame, but I do question how good a teammate Magee was. I mean, the character factor is an issue for him.”

So with the rise of advanced metrics, which may lead voters to consider the statistical accomplishments of particular players in a new light, it is conceivable that the non-quantitative factors — which are also important — may be crowded out by the quantitative ones. That issue is a factor in considering the case of Dahlen, for instance.

“Defense is hard to measure, and so that’s where a guy like Bill Dahlen has really been recognized more since the advanced metrics are now giving him a ton of credit for his defense,” Morris said. “It seems to me that Dahlen is getting more credit from the advanced metrics than he got from contemporaneous accounts of his defense. You are really balancing two things there: If people who saw him play didn’t seem that excited about him but these metrics are giving him all this credit, then which way do you go? So I think that’s a tough dilemma when it comes to deciding if Dahlen is worthy of the Hall of Fame.”

Deane offered a complementary assessment: “There may be valid reasons why voters of a certain period didn’t put somebody in the Hall of Fame,” Deane said. “Albert Belle is a more modern example. I am not saying that they’re right or wrong, but the voters of his era decided that Belle was not worthy of the Hall of Fame, even though he has some impressive numbers. And 50 years from now, when you’ll have lost most of the contemporary observers, voters then might just look at the numbers and say, ‘Why isn’t Albert Belle in the Hall of Fame?’ In a way, it could wind up being dismissive of the contemporary observers because those voters had their reasons for not putting him into the Hall.”

Lyle Spatz evaluated both the strengths and weaknesses of Dahlen’s (pronounced DAY-len, according to Spatz) case for the Hall of Fame in his 2004 biography Bad Bill Dahlen: The Rollicking Life and Times of an Early Baseball Star, where Dahlen’s ferocious temper was on full display. In terms of evaluating playing skill, Spatz emphasizes that where a player ranked relative to his contemporaries is key.

“As we seem to be moving more and more to voters depending on the analytics of today to judge players, I still like to judge them in their own time,” Spatz said. “I think that Dahlen was the best shortstop of the decade of the 1890s. He and George Davis, and then, of course, [Honus] Wagner. You look at the number of errors Dahlen made, and you’d say he couldn’t make a high school team now. But, of course, putting it in context, people realize that you made a lot more errors in those days playing on those fields with those gloves.

“I really like to judge players in the context of their times, as best as I can. And when you’re researching a book on a player and you’re reading what so-and-so said about him in real time, it gives you a different look. Sometimes, people say online that Derek Jeter, for instance, is not really that good based on the measurable factors. But if I have a team, I want Derek Jeter as my shortstop. And, of course, it’s so obvious that perhaps some people don’t believe it, but you cannot judge a player specifically on his numbers. There are intangibles.”

Rob Neyer, Senior Baseball Editor at FoxSports.com, suggests that advanced metrics can link Deadball Era players to modern ones, perhaps benefiting the candidacies of the former.

“The numbers I’ve seen suggest that Dahlen was an outstanding shortstop,” Neyer said. “That’s where Dahlen’s case is: as the Ozzie Smith or the Omar Vizquel of his era. Someone needs to make that case. The minute you can say that Bill Dahlen was Ozzie Smith by using analytic methods, you can generate some real traction for his Hall of Fame candidacy.”

Then there is Sheckard, who is clearly overshadowed by many of his better-known Cubs teammates.

Then there is Sheckard, who is clearly overshadowed by many of his better-known Cubs teammates.

Sheckard is perhaps best remembered for his 1903 season, when he led the National League in home runs (9) and in stolen bases (67), though he was never the most important player on a championship team.

“Jimmy Sheckard was a good ballplayer. He was an on-base guy, and I think that would be one of the narratives, as bases on balls weren’t really appreciated as much as they should have been,” Morris said.

Spatz, though, considers Sheckard to be the least-worthy of the players who are commonly mentioned as Deadball Era Hall of Fame candidates, and there seems to be only modest support for Sheckard’s election.

The scope of names of players with Deadball Era links mentioned by Deane, Morris, Neyer, Spatz, and Simon as at least potential Hall of Fame candidates is broad. They include Babe Adams, Ray Chapman, Wilbur Cooper, Larry Doyle, Larry Gardner, Fielder Jones, Tommy Leach, Sam Leever, Carl Mays, Deacon Phillippe, Jimmy Ryan, Wally Schang, Wildfire Schulte, Urban Shocker, Bobby Veach, and Hooks Wiltse.

Another commonly cited Deadball Era Hall of Fame omission is Gavy Cravath, who led the National League in home runs six times. “Cravath is a guy whom I always think is in, but he’s not,” Spatz said.

The inclusion of baseball historians on the 2012 selection committee for pre-1947 players emphasizes a heightened level of rigor in examining early baseball candidacies. With the chance to have other Deadball Era players elected to the Hall of Fame in 2015, it is also conceivable that many of these players will be considered for decades to come.

“The Hall of Fame has never formally said, ‘Okay, we’re going to look at this group one more time, and that’s it,’” Deane said. “And no matter what you do, you’re going to have people saying, ‘Well, it’s good Sherry Magee’s in, but why isn’t Jimmy Ryan in?’ As you might expect, you’re going to make some people happy and some people unhappy. I’ve always been a hardliner when it comes to Halls of Fame — they should be for the best of the best.”

JOHN McMURRAY is chair of SABR’s Deadball Era Research Committee. Contact him at deadball@sabr.org.