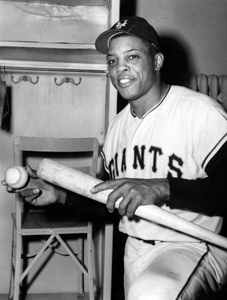

Willie Mays at The Polo Grounds

This article was written by John J. Burbridge Jr.

This article was published in Willie Mays: Five Tools (2023)

Willie Mays batted .298 in 399 career games at the Polo Grounds and hit 98 home runs. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Certain ballparks complement the strengths of specific players. Yankee Stadium, which opened in 1923, was termed The House That Ruth Built. One reason for such a slogan was the short distance to the right-field stands, which seemed to cater to the powerful left-handed stroke of Babe Ruth.1 While the benefits of Ruth playing in Yankee Stadium were immediate, it took many years for a player to take advantage of the vast center field at the Polo Grounds. That player was Willie Mays.

New York City was home to playing fields termed the Polo Grounds from 1876 through 1963. The first Polo Grounds, at 110th Street and Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, was used for polo. In 1880 the New York Metropolitans, owned by John B. Day, began playing baseball at the site. Day moved the Metropolitans to the American Association in 1883 while also taking control of a team from Troy, New York. That team was called the Gothams and played in the new National League. They became the Giants in 1885. Both teams played at the Polo Grounds after a second field was built on the site. The Metropolitans ceased operating after the 1887 season.

In 1889 New York City had plans for the 110th Street site and Day looked for a new home for the Giants. He settled on a field in Coogan’s Hollow at 155th Street and Eighth Avenue in Manhattan for the new Polo Grounds. The Giants quickly got a neighbor, the New York team in the newly formed Players’ League. They played their games at a field adjacent to the new Polo Grounds, Brotherhood Park. The Players’ League folded after one year. The Giants decided Brotherhood Park was a better venue and made it their home field. It was also called the Polo Grounds.2

A fire just after the 1911 season began caused widespread damage to the wooden ballpark. The new ballpark, built with steel, concrete, and marble, was ready three months later.3 This version of the Polo Grounds became the home of the Giants until they moved to San Francisco at the end of the 1957 season.

This last manifestation of the Polo Grounds was unique among ballparks. The right-field foul pole was just 258 feet from home plate while left field was 277 feet. However, both the right-field and left-field stands extended straight out, finally curving as they reached the center-field bleachers. The power alleys in both right and left were approximately 450 feet from home plate while center field was even more distant, 483 feet. A superb center fielder was required to cover this wide expanse of ground. Over the years, the Giants had good center fielders but it wasn’t until 1951 that the team found a perfect fit in Willie Mays.

His journey to the Polo Grounds began in Birmingham, Alabama, where he joined the Black Barons of the Negro American League in 1948.

On a barnstorming trip to Birmingham, Roy Campanella became excited at seeing Mays patrol center field and throwing out the speedy Larry Doby at home plate.4 He told the Brooklyn Dodgers they had to see this kid. They sent a scout, Wid Matthews, to look him over. Apparently, Mathews was not impressed, saying, “He could not hit a curve ball.”5 The Dodgers passed on Mays.

Another team that looked at Mays was the New York Giants. In a quirk of fortune, Giants scout Eddie Montague was looking at another Black Barons player when he spotted Mays. Montague said Mays was the greatest young player he had ever seen. The Giants quickly signed Mays in 1950 with a bonus of $4,000 and a salary of $250 per month.6 Fate had intervened as Mays was destined for the Polo Grounds, not Ebbets Field, which was the Dodgers’ home ballpark.

The Giants assigned Mays to the Trenton team in the Class-B Interstate League. After hitting .355 and playing a flawless center field at Trenton, he was invited to join the top farm team of the Giants, the Minneapolis Millers, for 1951 spring training. In a game with the parent club, Mays had a double and a home run and attracted the attention of Giants manager Leo Durocher. Durocher wanted Mays to play center field for the Giants in 1951. Horace Stoneham, the Giants owner, felt he needed more time in the minor leagues, given that he was only 19. Mays began the season with Minneapolis.

The Giants got off to a slow start while Mays was starring with the Millers. As the Giants struggled, Durocher kept lobbying Stoneham to bring Mays up to the majors. In late May Durocher finally got his wish and Mays became a Giant. He was no stranger to the Polo Grounds, having played several games there with the Black Barons.

Mays made his debut on May 25 in Philadelphia’s Shibe Park. He went hitless and also struggled in the field. In the next two games in Philadelphia, he also went hitless. Returning to the Polo Grounds for a three-game series against the Boston Braves, Mays hit a home run over the left-field roof against future Hall of Famer Warren Spahn in the first inning. That was his only hit in the series. In the Giants’ next game, against the Pittsburgh Pirates, he went 0-for-5. He was 1-for-26 in his first seven games.

After the game with the Pirates, Mays was found crying in the clubhouse. Coaches Herman Franks and Freddie Fitzsimmons called for Durocher. Mays told Durocher he couldn’t hit big-league pitching and should be sent to the minors. Durocher responded, “As long as I’m the manager of the Giants, you are my center fielder. Tomorrow, next week, next month. You’re here to stay. With your talent, you’re going to get plenty of hits.”7

Durocher also had some advice for Mays about his difficulties at the plate. He had noticed that Mays was turning over his right hand too quickly when swinging, leading to groundballs to the left side. He wanted Mays to take the ball to right field. Finally, he told Mays to pull up his pants as a way to raise his strike zone.8

Durocher also had the following guidance for Mays as he patrolled center field: “You have to catch balls line to line. The ball goes to the left, you gotta be over there. The ball goes to the right, you gotta be over there. Wherever the ball goes in the outfield, you gotta catch it.”9 Buck O’Neil summarized how well Mays pursued fly balls by stating, “While there are players faster than Mays, no one was faster while a fly ball was in the air.”10

In the next game against the Pirates, on June 2, Mays was moved from third in the batting order to eighth. He responded by going 2-for-4 as the Giants won 14-3. Mays then went 13-for-33 in the final nine games of the homestand. There were no further concerns about him at the plate. In addition to his improved hitting, Mays was playing a flawless center field after some misfortune in that first game.

As the season progressed, the Dodgers surged and had a 13-game lead over the Giants on August 11. On the 14th the two teams began a three-game series at the Polo Grounds. The Giants won the first game, 4-2. The second game pitted Ralph Branca of the Dodgers against Jim Hearn of the Giants. With the two teams tied 1-1 after seven innings, Billy Cox led off the Dodgers’ eighth with a single. Jackie Robinson pinch-hit for Wayne Terwilliger and flied out. Hearn committed a balk, moving Cox to second. Branca followed with a single, moving Cox to third and bringing up the dangerous Carl Furillo.

With runners on first and third, Furillo hit a fly ball to right-center field. Joseph Sheehan of the New York Times had the following description of what happened next: “It looked plenty deep enough to bring in Cox, especially since Mays had to run a long way to get the ball. But Willie, making a complete whirling pivot on the dead run, cut loose with a tremendous peg that boomed into [Wes] Westrum’s mitt in perfect position for the catcher to tag the sliding Cox.”11 Eddie Brannick, the Giants road secretary since 1922, said, “I’ve seen [Tris] Speaker, [Joe] DiMaggio, [Terry] Moore, all of them, but I’ve never seen anything like that throw. This kid made the greatest throw I ever looked at.”12

Both the Dodgers and Giants players were in disbelief. All the players and fans were certain the Dodgers were going to take the lead but the game remained tied after the inning-ending double play. Mays was first up in the bottom of the eighth and received a standing ovation. He singled to center field and scored on a two-run home run by Westrum. The Giants won, 3-1.

Whether this play or game proved to be the catalyst, the Giants went on a prolonged winning streak and tied the Dodgers for the National League lead during the last week of the season. They remained tied at the end of the season and a three-game playoff was needed to decide the pennant winner. That playoff ended with the Bobby Thomson home run that gave the Giants the pennant. Mays was on deck when Thomson hit the home run.

The 1951 season had to be considered a success for Mays. Durocher’s contribution cannot be underestimated. Durocher was considered a tough taskmaster who demanded the utmost from his players. He also realized that not all players respond to such treatment. Durocher understood that Mays, a Black 20-year-old playing and living in a strange environment, had his confidence shaken in his first seven games in the major leagues. If Durocher employed those tough tactics with Mays, his performance may have suffered. Instead, Durocher softened his approach and reassured Mays that he belonged in the major leagues. Bill Rigney, who succeeded Durocher as Giants manager after the 1955 season, gave the former skipper a lot of credit for Mays’ development.13

Monte Irvin also played a big part in helping Mays make the transition by ensuring that he did not develop any bad habits in New York City, the city that never sleeps. Mays said: “Monte taught me how to treat others and how to be treated. He played the game right and treated people right. He was a thinker. He made sure I didn’t get into trouble.”14

Another individual who had a major influence on Mays in 1951 was Frank Forbes, a Harlem boxing promoter who was assigned by the Giants to be more or less Mays’ guardian. Forbes wanted a good home environment for Mays and found a place on the first floor of a home owned by David and Ann Goosby at the corner of 155th Street and St. Nicholas Avenue, a short walk to the Polo Grounds. Mrs. Goosby prepared meals for Mays, washed his clothes, and provided sage advice. Mays also enjoyed playing stickball with the neighborhood kids. With Irvin, Forbes, and Mrs. Goosby, Mays would have a difficult time getting into trouble.

When Mays returned home to Alabama, he received his draft notice. The Korean War was still being fought and Congress had approved an expansion of the US military. Mays pursued a deferment given that his income was supporting his family. His deferment request was denied and he was told to report for duty on May 29, 1952. As a result, he went to spring training and began the 1952 season with the Giants before joining the Army.

At Fort Eustis, Virginia, Mays played a significant amount of baseball on the base team. While in the Army he perfected his trademark basket catch. He had seen Bill Rigney catch infield popups using that catch. Mays felt that making the catch close to his waist gave him a greater opportunity to retrieve the ball quickly and make any necessary throw. (Since Mays adopted such an approach, no other outfielder comes to mind who has made use of the basket catch.)

Alvin Dark, Monte Irvin, Wes Westrum, and Willie Mays, left to right, kept the Giants in the thick of many pennant races. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

After the 1953 season, the Giants made a significant trade with the Milwaukee Braves. The Giants received left-handed pitchers Johnny Antonelli and Don Liddle and others for Bobby Thomson and Sam Calderone. Antonelli would have a big impact on the 1954 season.

Mays had a banner year with the Giants in 1954 as they won the pennant. He showed no rust after serving in the Army. In fact, it was somewhat obvious that playing Army baseball had enhanced his strength, maturity, and hitting skills. In his first 80 games, he hit 30 home runs. Sportswriters and fans were wondering if he was a threat to Babe Ruth’s record of 60 home runs. However, Durocher had another idea. He suggested to Mays that rather than hit home runs, he should be hitting to all fields and pursuing the batting championship.

The strategy worked as Mays went into the final day of the season battling teammate Don Mueller and Dodgers star Duke Snider. Mays went 3-for-5 and won the title with an average of .345. He hit 41 home runs and had 110 RBIs. He was voted the league’s Most Valuable Player.

The Cleveland Indians won 111 games as they easily captured the American League pennant. The first game of the World Series was played on September 29 with pitcher Sal Maglie starting for the Giants and Bob Lemon for the Indians. The Indians scored two runs in the top of the first but the Giants tied it in the bottom of the third. The game stayed tied as the two teams entered the top of the eighth inning.

Leading off for the Indians, Larry Doby drew a walk. Al Rosen’s single put runners on first and second with no outs. Durocher replaced Maglie with Don Liddle. The first batter Liddle faced, Vic Wertz, already had three hits and two RBIs. With a 2-and-1 count, Liddle’s next pitch was over the middle of the plate and Wertz hit a long fly, possibly 450 feet, to center field.

As soon as the ball was hit, Mays turned, ran with his back to the plate, and pounded his glove. The New York Times’ John Drebinger described what followed: “Traveling on the wings of the wind, Willie caught the ball directly in front of the green boarding facing the right-center bleachers and with his back still to the diamond.”15

Once he caught the ball, Mays had the presence of mind to realize Doby would be tagging up at second base. If he didn’t get the ball back quickly, Doby might even score. So after making the catch, Mays pivoted and unleashed a throw to second baseman Davey Williams, holding Doby at third. Even with Doby at third and only one out, the Indians failed to score.

The Giants ultimately won the game, 5-2, as Dusty Rhodes pinch-hit a three-run home run in the bottom of the 10th. While Rhodes became a hero, the game was really won in the top of the eighth with the catch and throw that Willie made. Whenever World Series highlights are shown, this play tends to be front and center. It has become known as “The Catch” and it only could have happened at the spacious Polo Grounds.

The Giants went on to win the next three games and sweep the Series. At the age of 23, Willie Mays had been in two World Series, won a batting title and an MVP, and made “The Catch.”

Mays followed his 1954 performance with another excellent year in 1955. He hit 51 home runs as Durocher decided the Giants needed more power and asked Mays to hit for the fences. However, the year was bittersweet. During the last game of the season, Durocher pulled Mays aside and told him he would not be back in 1956. Tearfully, Mays responded, “But Mr. Leo, it’s going to be different with you gone. You won’t be here to help me.”16 Then Durocher told him, “Willie Mays doesn’t need help from anyone.”17

Rigney was named the next Giants manager. The former Millers skipper decided to establish a new culture and treat all the players equally. Rigney realized that there were some players who weren’t happy with Durocher’s treatment of Mays. Rigney publicly criticized Mays and even fined him for not running out a pop fly to the catcher. In addition to the tension between Rigney and Mays, the Giants were struggling to win games. As a result, Dark and Whitey Lockman were traded but the Giants still stumbled and finished sixth. Mays failed to bat .300, finishing at .296. He did become the first National League 30-30 player with 36 home runs and 40 stolen bases.

While the relationship between Rigney and Mays improved in 1957, the Giants still struggled. In addition, there was considerable speculation that the Giants would be moving after the season, The 1956 attendance showed a steep decline and 1957 was even worse. In addition, the ballpark was deteriorating. In an 8-to-1 vote, the Giants’ board of directors made it official. They would be playing in San Francisco in 1958.

In the final game of the season at the Polo Grounds, Mays came up in the seventh inning with the Giants losing 7-1. He hit a groundball to third base but beat it out running full speed in a rather meaningless game, exciting the crowd. Mays came to bat once again in the bottom of the ninth. The small crowd of 11,606 greeted him with great applause. They recognized the excitement he had provided to all baseball fans and to New York City since 1951.

While it appeared that the Giants and Mays were never to play again in the Polo Grounds, they did return. The New York Mets began play as an expansion franchise in 1962. The Polo Grounds became their first home ballpark. On June 1the Giants and Mets began a four-game series there. Mays was greeted by the fans with “Say Hey Willie” signs and loud cheers. In the New York Times Arthur Daley wrote, “The center field turf at the Polo Grounds looks normal this weekend for the first time in five years. Willie has come home.”18 Mays did not disappoint as he hit three home runs in the four-game sweep.

While Willie Mays did return to New York to play for the Mets in 1972 and 1973, he was not the same player who roamed center field at the Polo Grounds in the 1950s. During those years, all baseball fans and especially Giants fans were thrilled by his performance. His fielding and “The Catch” facilitated by the spacious Polo Grounds outfield will be long remembered. As Donald Honig wrote, “Putting Mays in a small ballpark would have been like trimming a masterpiece to fit a frame.”19

DR. JOHN J. BURBRIDGE JR. is currently Professor Emeritus at Elon University, where he was both a dean and professor. While at Elon he introduced and taught Baseball and Statistics. He has authored several SABR publications and presented at SABR conventions, NINE, and the Seymour meetings. He is a lifelong New York Giants baseball fan. The greatest Giants-Dodgers game he attended was a 1-0 Giants’ victory in Jersey City in 1956. The sole run was a Willie Mays home run off Don Newcombe. Yes, the Dodgers did play in Jersey City in 1956 and 1957. John can be reached at burbridg@elon.edu.

NOTES

1 Chris Landers, “Yankee Stadium’s Short Porch in Right Field Is Responsible for Some of Baseball’s Biggest Moments,” MLB.com, January 29, 2019, https://www.mlb.com/cut4/why-does-yankee-stadium-have-a-short-porch-in-right-field-c303279930.

2 Stew Thornley, “Polo Grounds (New York),” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/park/polo-grounds-new-york/, accessed online on December 1, 2022.

3 Thornley.

4 John Saccoman, “Willie Mays,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/willie-mays, accessed online on December 1, 2022.

5 Saccoman.

6 Saccoman.

7 James S. Hirsch, Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend (New York: Scribner, 2010), 103.

8 Hirsch, 104.

9 Willie Mays and John Shea, 24: Life Stories and Lessons from the Say Hey Kid (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2020), 65.

10 Hirsch, 102.

11 Joseph M. Sheehan, “Mays Helps Hearn Topple Brooks, 3-1,” New York Times, August 16, 1951: 38.

12 Jason Aronoff, Going, Going … Caught! Baseball’s Great Outfield Catches as Described by Those Who Saw Them, 1887-1964 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2009), 155.

13 Mays and Shea, 61.

14 Mays and Shea, 63.

15 John Drebinger, “Giants Win in 10th From Indians, 5-2, on Rhodes’ Homer,” New York Times, September 30, 1954: 1.

16 Hirsch, 244.

17 Hirsch, 245.

18 Hirsch, 352.

19 Hirsch, 104.