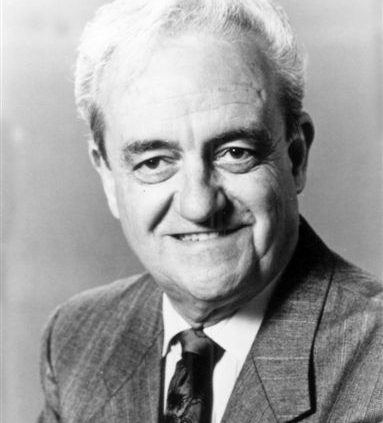

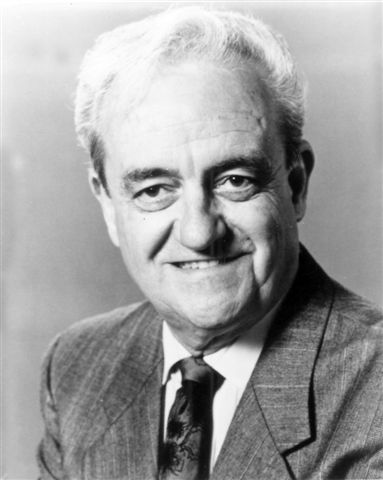

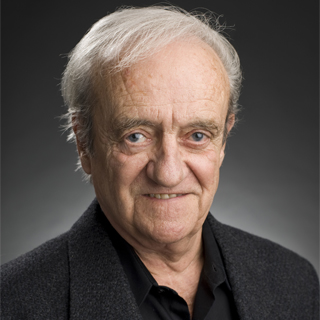

In Memoriam: Roland Hemond

By Jacob Pomrenke

Roland Hemond was a scout at heart, always on the lookout for the right people who could help his teams succeed, on and off the field. The three World Series rings he earned were proof of the on-field achievements, but the longtime SABR member’s legacy in baseball ran much deeper off the field.

Roland Hemond was a scout at heart, always on the lookout for the right people who could help his teams succeed, on and off the field. The three World Series rings he earned were proof of the on-field achievements, but the longtime SABR member’s legacy in baseball ran much deeper off the field.

When he was honored by the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2011 with the Buck O’Neil Lifetime Achievement Award, Hemond memorably unveiled a long list of names that stretched across half the stage — all the people he wished to thank for his success. The list of people who could give thanks to him was exponentially longer. During Hemond’s seven decades in the game, there was hardly a single person working in baseball whose life and career was not influenced in some way by the soft-spoken front-office executive and ambassador who never forgot a name.

Hemond drafted Hank Aaron’s first contract when he was the assistant farm director for the Milwaukee Braves; as general manager of the Chicago White Sox, he tabbed Tony La Russa for his first managerial job; and he was a key architect in building the expansion Los Angeles Angels and Arizona Diamondbacks from scratch, nearly 40 years apart. As a three-time recipient of MLB’s Executive of the Year Award (1972, ’83, and ’89), Hemond established innovations in front-office strategy as the game moved into the free-agency era and beyond. He was also the creator of the successful Arizona Fall League, baseball’s “graduate school” for top prospects in the minors.

The “family tree” of executives hired or mentored by Hemond included some of baseball’s most successful and significant figures: David Dombrowski, Walt Jocketty, Doug Melvin, Derrick Hall, Dan Evans, Joe Garagiola Jr., Ken Williams, Tim Purpura, and Bill Smith Jr.; plus Jerry Krause, who first worked under Hemond as a White Sox scout before switching sports to build one of basketball’s most dominant dynasties as general manager of the NBA’s Chicago Bulls.

Through it all, Hemond was a man of enduring kindness and integrity, always willing to lend a helping hand or offer advice to anyone who asked for his respected guidance. He died at age 92 of natural causes on December 12, 2021, survived by his wife, Margo; five children, Susan, Tere, Robert, Jay, and Ryan, four grandchildren; and baseball friends and protégés in every organization.

Hemond was so beloved that on the day he was fired as White Sox GM in 1985 after 12 seasons, team chairman Jerry Reinsdorf, one of his closest friends, spent the entire press conference singing his praises. “He was a prince,” Reinsdorf told Jerome Holtzman of the Chicago Tribune. “I can never say enough about Roland Hemond.”

Hemond’s influence was most keenly felt by baseball’s “unsung heroes”: the scouts and other front-office employees who put in long hours behind the scenes to keep the game running smoothly. In 2001, SABR’s Scouts Research Committee established an award honoring baseball executives who demonstrated a lifetime commitment to professional scouts and player development. No one was more dedicated to scouts than Hemond, who won the first award and became its namesake thereafter.

As a co-founder of the Professional Baseball Scouts Foundation, Hemond was instrumental in providing financial assistance to any talent evaluators who had fallen on hard times. As president of the Association of Professional Baseball Players of America, he also helped provide college scholarships to former players and others connected with the game. In 1983, he single-handedly convinced baseball owners to approve a pension plan for non-uniformed personnel, which he later called his greatest contribution to the sport. It was a decision that positively affected thousands of families. Like his old boss, Hall of Fame executive Bill Veeck, he was always thinking of “the little guy.”

“They say the scouts are the unsung heroes,” Hemond told SABR’s Bill Nowlin in 2001. “I’ve heard that since I broke in, in the early ’50s. … So I always say, ‘Well, let’s sing their praises.’ I want to see them get recognition that they so justly deserve. They never get any headlines. They never get any recognition.”

Hemond, who wrote the foreword to SABR’s 2011 book on baseball scouts, Can He Play: A Look at Baseball Scouts and Their Profession, realized a dream two years later when the Baseball Hall of Fame opened a permanent exhibit honoring baseball scouts, “Diamond Mines.”

“A general manager is only as good as his scouts,” Hemond once said. “I was privileged to have a bunch of them who were both great talent evaluators and loyal. … No matter what contribution you might have made, you didn’t do it by yourself.”

The modest Hemond never expected to make the contributions he made, often calling himself the “luckiest guy in baseball.” Born on October 26, 1929, in Central Falls, Rhode Island, to Ernest and Antoinette Hemond, Roland grew up speaking French until he was six years old — a skill he later put to use by announcing a trade with the Montreal Expos in his mother’s tongue at the winter meetings.

He fell in love with the Boston Red Sox during Jimmie Foxx’s MVP season in 1938 and spent a lot of time at nearby McCoy Stadium in Pawtucket, with occasional trips to Fenway Park. He played ball through high school, even matching up in an American Legion game once against future major-league GM Lou Gorman. After graduation, Hemond began a four-year stint in the Coast Guard.

He got his start in baseball while on leave in Florida during spring training of 1951. He hitch-hiked to see his cousin Ray Lague, a pitcher at the Pittsburgh Pirates’ camp in Deland, and was eventually introduced to Charlie Blossfield, GM of the Boston Braves’ farm team in Hartford, Connecticut. That same day, he met his future wife, Margo, the daughter of Braves executive John J. Quinn. When they wed in 1958, Roland married into a family of baseball royalty. John Quinn helped lead the Braves to three World Series as GM in Boston and Milwaukee, while his father Bob was a major-league executive for three decades before serving as director of the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. Two future generations of Quinns (and Hemonds) also worked in baseball, giving the extended family a presence in the game for parts of three different centuries.

Blossfield hired Hemond for $28 per week to be a jack-of-all-trades for the Hartford Chiefs, selling tickets and concessions, sweeping the floors, and doing other odd jobs at Bulkeley Stadium. Near the end of the season, Blossfield recommended Hemond to Boston Braves farm director John Mullen. Hemond spent the rest of the decade as the Braves’ assistant farm director under Mullen’s tutelage, moving with the franchise in 1953 to Milwaukee, where they won two National League pennants and the 1957 World Series.

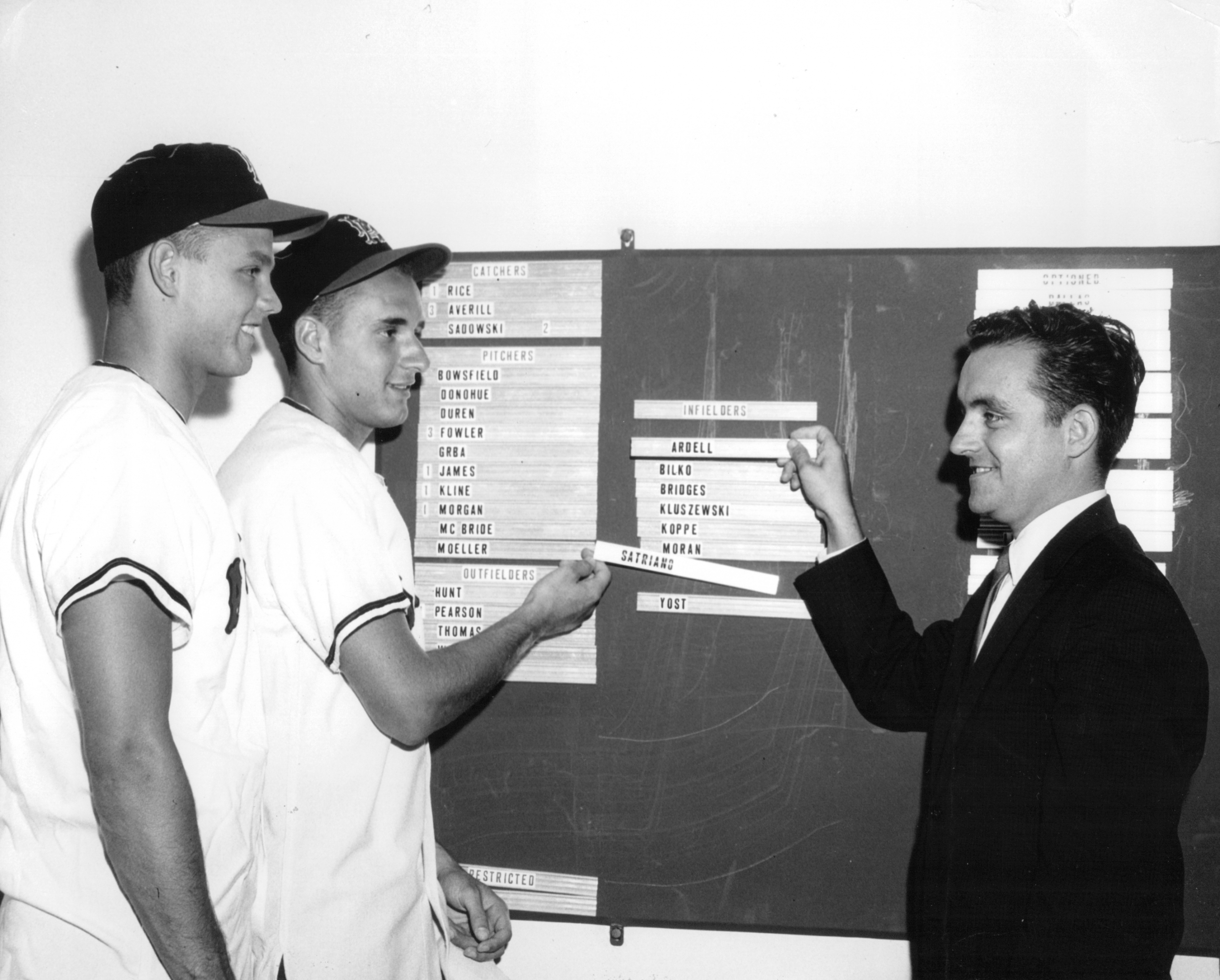

Los Angeles Angels executive Roland Hemond (right) talks with two 1961 USC bonus babies fresh from the 1961 College World Series championship, first baseman Dan Ardell (far left) and third baseman Tom Satriano (near left), whom he signed that July. (COURTESY OF DAN ARDELL)

In 1961, Hemond was hired at age 31 by the expansion Los Angeles Angels to oversee their farm system. He recalled, “I had been told in Milwaukee that I was too young to be a scouting director and six weeks later I was farm and scouting director with the Angels and I said, ‘Boy, did I mature in six weeks.’” In their second season, the 1962 Angels surprised everyone by leading the American League standings as late as the Fourth of July and finishing in third place with an 86-76 record. Hemond spent 10 seasons with the Angels before he and his good friend, the manager Chuck Tanner, moved on to the Chicago White Sox in a package deal in 1970.

Although Hemond eventually worked for five different major league clubs, he is most known for his time with the White Sox, with whom he had two extended stints — from 1970 to 1985 and again from 2001 to 2007 — under three ownership regimes. (“I led the league in owners,” he liked to say.) He played a pivotal role in one of the most dramatic turnarounds in baseball history, inheriting a team that lost 106 games and was near bankruptcy when he arrived as director of player personnel in 1970. He acquired Dick Allen from the Dodgers and the powerful slugger won the American League MVP in 1972 as the Sox won 87 games and captured the hearts of 1.1 million fans at Comiskey Park. Hemond was named MLB Executive of the Year for the first time by The Sporting News.

In midseason 1973, Hemond took over for Stuart Holcomb as the White Sox’s general manager, a position he held for the next 12 years. Owner John Allyn sold the team in 1975 to Bill Veeck, but Hemond was asked to stay on as GM and he thrived under the future Hall of Fame executive. The pair made a splash at their first winter meetings together. Veeck, perpetually short on funds but long on creativity, instructed his right-hand man to “let your imagination run rampant.” In one of baseball’s most colorful winter meetings tales, an inspired Hemond set up a table in the lobby of a Florida hotel with a sign that said “Open for Business.” With rival GMs and sports writers looking on in disbelief, the White Sox made four trades before midnight and overhauled their fifth-place roster. Of his time with Veeck, Hemond recalled, “What a great five years of adventure with this legendary genius … a tremendous experience that I greatly treasure and will forever relish.”

As general manager, Hemond built two of the most popular teams in White Sox history, 1977’s “South Side Hit Men” and the “Winning Ugly” division champions of 1983, when he was again named Executive of the Year by United Press International. By then, the financially strapped Veeck had sold the team to Jerry Reinsdorf and Eddie Einhorn, who retained Hemond as general manager when they took control. Hemond put his stamp on the franchise by bringing in three players who would become iconic figures at Comiskey Park: Harold Baines (via the draft) in 1977, Carlton Fisk (free agent) in 1981, and Ozzie Guillen (trade) in 1984.

But Hemond’s most significant move was in hiring a 34-year-old former infielder, Tony La Russa, as the White Sox’s manager in August 1979. In the first stop of a managerial career that eventually would land him in the Hall of Fame, La Russa led Chicago to the AL West title in 1983 and won Manager of the Year honors. La Russa moved on to the Oakland A’s in 1986, a year after Hemond had been replaced as White Sox GM by Ken “Hawk” Harrelson. Hemond took a job with the commissioner’s office in New York, an experience he said was one of the most enlightening of his career. “You have greater respect when you’re not working just with your own ballclub,” he recalled.

In 1988, Hemond began his first season as GM of the Baltimore Orioles, who welcomed him by losing their first 21 games, the worst start in major-league history. “It wasn’t a good club. I used to tell myself, ‘Well, I didn’t create it, I inherited it,’” Hemond recalled. Like he had done with the White Sox in the early years, he set about to overhaul the O’s roster, completing trades for prospects Curt Schilling, Brady Anderson, and Chris Hoiles. The result was another dramatic turnaround, from a 107-loss team in 1988 to a surprising contender in 1989 that battled for the AL East crown until the final weekend. Hemond once again earned Executive of the Year honors from The Sporting News.

Although Baltimore never made the postseason during his eight-year tenure, Hemond left the Orioles in much better shape than he found them, setting them up for two playoff runs in the mid-1990s. In 1996, Hemond moved west to become senior executive vice president for the fledgling Arizona Diamondbacks, helping to build another expansion team from scratch as he had done decades before in California. Once again, his new club experienced great success in its second season, as the Diamondbacks won 100 games and the NL West title in 1999, drawing more than 3 million fans to Bank One Ballpark.

Although Baltimore never made the postseason during his eight-year tenure, Hemond left the Orioles in much better shape than he found them, setting them up for two playoff runs in the mid-1990s. In 1996, Hemond moved west to become senior executive vice president for the fledgling Arizona Diamondbacks, helping to build another expansion team from scratch as he had done decades before in California. Once again, his new club experienced great success in its second season, as the Diamondbacks won 100 games and the NL West title in 1999, drawing more than 3 million fans to Bank One Ballpark.

Hemond returned to the Chicago White Sox in 2000 to serve as an adviser to GM Kenny Williams, missing out by one year on the Diamondbacks’ World Series championship season. “I don’t regret (leaving Arizona),” he told SABR’s Bill Nowlin following the 2001 World Series. “I’m happy for them. I thoroughly enjoyed their accomplishment, and you know that during the period of time you were there you made some contributions that led to their success.” The Diamondbacks later had a commemorative ring made for Hemond, who wore it proudly.

A few years later, Hemond got a long-awaited chance to taste the champagne when the White Sox ended an 88-year championship drought by sweeping the Houston Astros in the World Series — clinching the title in Game Four on his 76th birthday. He celebrated in the locker room after a World Series for the first time since 1957, when his Milwaukee Braves had defeated the New York Yankees in a memorable fall classic.

Hemond spent his final years in baseball as a special assistant to Diamondbacks CEO Derrick Hall beginning in 2007, representing the team at the amateur draft and serving as a global ambassador for the sport. He spent much of his time mentoring the next generation of front-office executives, encouraging players at all levels to finish their education, and taking care of the former players, scouts, and team employees that he cared about most.

His selection as the Hall of Fame’s second-ever Buck O’Neil Lifetime Achievement Award recipient in 2011 brought increased exposure to his long and meritorious service in baseball. Four organizations named awards in his honor: SABR, the White Sox, the Diamondbacks, and Baseball America. The Diamondbacks also named a youth baseball field in his honor in 2015.

“I believe he’s the most beloved man of our generation,” La Russa said when Roland Hemond Field was dedicated in Phoenix. “He enjoyed every moment. Spirit, honesty, integrity … he’s just a great human being. He treated everyone like family. There’s nobody like him.”

“No one has had more influence on the game of baseball than Roland Hemond,” Hall added. “He’s touched almost everyone’s life in Major League Baseball. It’s amazing how many people you talk to at the winter meetings or when you go to the playoffs or who’s working in the minor leagues, and they say, ‘I got to spend time with Roland Hemond.’ And then you think, ‘I got to spend time with him, too.’ He takes the time with everyone — to advise them, to direct them, to guide them. You look at the number of general managers, scouting directors, managers, and owners that he’s helped. I, too, am one of them. … He is truly the best.”

Originally published: December 13, 2021. Last Updated: December 13, 2021.