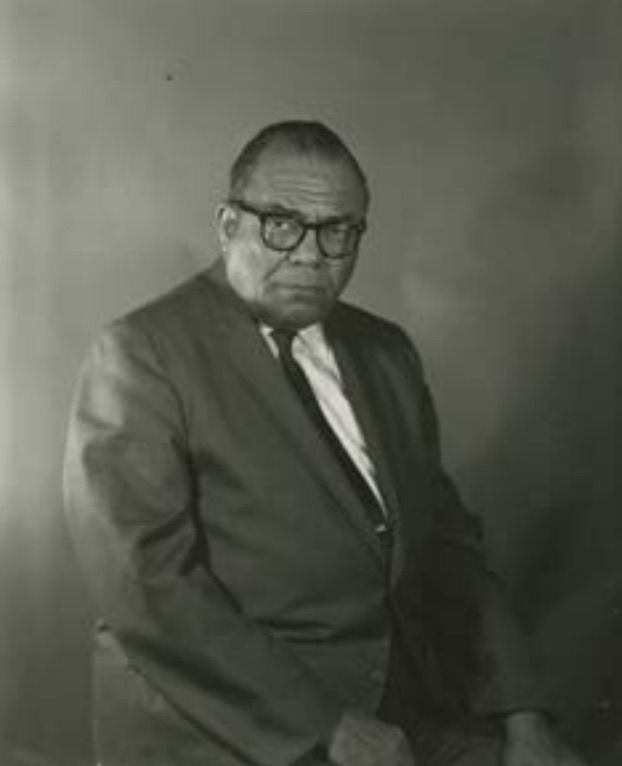

Tom Hayes

Tom Hayes is a footnote in baseball history. To the extent that he is remembered at all, it is for selling 19-year-old Willie Mays to the New York Giants and setting him on his path to immortality. However, in his time, this shrewd, gruff man was a towering figure, a pioneer whose impact in the black community spread far beyond baseball.

Tom Hayes is a footnote in baseball history. To the extent that he is remembered at all, it is for selling 19-year-old Willie Mays to the New York Giants and setting him on his path to immortality. However, in his time, this shrewd, gruff man was a towering figure, a pioneer whose impact in the black community spread far beyond baseball.

Hayes’ father, Thomas Sr., was nothing if not determined. Born outside Richmond, Virginia, in 1868, he moved with his family to Tennessee as a child and toiled on the family farm until moving to Memphis, Tennessee, at age 16. He worked there as a porter for a decade before being bitten by the entrepreneurial bug.

That bite was particularly nasty. Hayes opened three grocery stores, all of which failed. Then he opened a barbershop, despite having no experience as barber. That enterprise apparently went as well as one might expect. After a stint as a traveling salesman, Hayes made yet another stab at running a grocery store. Then some good fortune finally came his way, although not in the way that he had planned. In the spring of 1902, after the death of a local undertaker, a friend persuaded Hayes to go into the funeral business. Again, he had no experience in the field, but he did have $1,400 in capital and a large storage shed next his store that could serve as a makeshift mortuary.1

It may have sounded like a harebrained notion, but in fact Hayes had stumbled onto one of the few paths to prosperity open to African-Americans in the pre-civil-rights South. A proper funeral was particularly important to blacks, who feared the ignominy of a burial in a pauper’s grave. Moreover, when it came to the African-American community, white funeral directors tended to the dead with the same disregard they had for the living. To illustrate the point, a black funeral director in Raleigh, North Carolina, told the tale of a white counterpart showing up at the home of a black family that had suffered a loss, hoisting the coffin onto the porch, and then refusing to help the family lay the body inside. “We don’t do anything about putting bodies in the coffin,” he sneered.2 On the day of the service, the man reserved his best horses for a white family, leaving the black family to transport the casket to the cemetery with mules. As Hayes put it to a gathering of the National Negro Business League, “The white undertaker doesn’t know the wants of our people and really does not care.”3

Thomas’s son, Thomas Henry Hayes Jr., was born on November 20, 1902. When he was a teenager, his father and his mother, Florence, purchased a stately turn-of-the-century home on South Lauderdale Street in Memphis and remodeled it, making space for his funeral business on the ground floor while the family lived upstairs. In later years, the Hayeses installed a fountain and a fish pond in front, in which neighborhood children would frolic on warm days. T.H. Hayes & Sons Funeral Home would operate out of this location for more than 90 years, becoming the oldest black-owned business in the city.

The younger Hayes attended several institutions of higher learning — Atlanta University, Lincoln University in Missouri, and the University of Illinois — before returning to manage the funeral home in the mid-1920s. He ran it along with his brother, Taylor, and Taylor’s wife, Frances, who learned the ins and outs of the profession quickly and became a driving force behind the business until her death at the age of 103 in 2010. “Everybody who was anybody, we buried them,” she said.4 In addition to his role in the family business, Taylor was president of the National Funeral Directors and Morticians Association and coached football at LeMoyne, a historically black college in Memphis.

In February 1929 Hayes married 17-year-old Helen Meadow, an intelligent, independent young woman who became a highly admired community figure in her own right. She graduated from LeMoyne in 1934 and earned a master’s degree in economics from Northwestern University, making her one of the first African-Americans in Memphis to complete an advanced degree. She taught at the Alonzo Locke Elementary School for 24 years, was one of the founders of the Vance Avenue Branch YWCA, and was active in the local chapter of the NAACP before she died of lung cancer in 1990.5 She and her husband raised two daughters.

Hayes’s father boasted business interests far and wide. He owned a copper mine in Arizona, was part-owner of a coal company in Oklahoma, had a stake in at least two life-insurance firms, and was vice president of a bank. Tom Jr. did not fall far from the tree. He was a natural businessman, good with numbers, and exceedingly competitive, and the sheer breadth of his interests was extraordinary. His grandson, Wesley Groves, called him a “jack of all trades.”6 Hayes helped organize a number of firms that primarily served black customers, including the Memphis Mortgage Company and Mutual Federal Savings and Loan. He helped create the Union Protective Life Insurance Company in 1933 and functioned in various capacities for that firm until its sale in 1980. Hayes had a hand in buses, hotels, restaurants and nightclubs, and even a brand of flour that he named Helen Ann Flour, after his daughter. “It was a lot of weird things going on,” she said with a chuckle years later.7

Outside of Memphis, Hayes was most widely recognized as the owner of baseball’s Birmingham Black Barons during their heyday in the 1940s. Through the 1920s and ’30s, the Black Barons bounced among the Negro Southern League (essentially the minor-league circuit) and the Negro American and National Leagues. Satchel Paige was the star of the Negro National League team that won a second-half pennant in 1927. The Great Depression wrecked the club’s finances and forced it to drop back to the Negro Southern League in 1931. After an ill-fated return to the Negro American League, the Black Barons temporarily ceased operations in 1939. That offseason Hayes, seeing an opportunity to buy low, swooped in and purchased the franchise at the winter meetings of the Negro American League in Chicago. He vowed, “Nothing will be left unturned in order to give Birmingham a good club.”8

Hayes was horizontally integrated, in a sense. His portfolio included the Rush Hotel in Birmingham, which catered to a predominantly black clientele and where visiting teams would stay when they came to town. He also owned the buses that the Black Barons used on road trips. Eddie Glennon, the amicable general manager of the white Birmingham Barons of the Southern Association, liked and respected Hayes. The two men had a deal that enabled the Black Barons to use Rickwood Field on Sundays or when the white ballclub was on the road, in exchange for a percentage of the gate receipts.

Hayes’s business partner was the short, fast-talking, and perpetually rumpled Abe Saperstein, impresario of basketball’s Harlem Globetrotters. Saperstein’s experience and connections enabled him to book the Black Barons in major venues, including Yankee Stadium, freeing them from the grueling tedium of constant barnstorming through backwater outposts. Hayes, meanwhile, handled most of the salary negotiations and player signings. It was a partnership that worked out well for everyone involved. Several players, including Basketball Hall of Famer Reece “Goose” Tatum, did double duty, playing for the Black Barons in the summer and the Globetrotters in the winter.

Hayes got right to it, hiring peripatetic manager Candy Jim Taylor, who had spent three years at the helm of the Chicago American Giants. He also signed talented rookies Dan Bankhead and Lyman Bostock, who would help form the backbone of the Black Barons through much of the decade. Outside the lines, Hayes did whatever he could do to lure fans to Rickwood Field. Among his promotions that first summer were a bathing-suit contest and a showdown that featured Olympic sprinter Jesse Owens racing against a motorcycle.9

It all paid off nicely. The Barons captured Negro American League pennants in 1943, ’44, and ’48, although they lost to the Homestead Grays in the Negro League World Series each time. Game day in Birmingham was like a holiday. “We drew more people in Birmingham than any city in the country,” asserted catcher Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe. “That’s one of the best baseball towns in the world. … Every Sunday was a sellout.”10

Hayes was not a man to be trifled with. He was stern and physically imposing, especially as he aged and put on weight. (His grandson described him as “D-shaped.”11) Although his players generally respected him as a businessman, he was hardly a beloved figure. “He was alright so long as you understood one thing,” Piper Davis cautioned. “If he told you the sun was going to rise in the west, you better be facing China.”12

Hayes took care of players who kept their mouths shut and did their jobs. Those who vocalized very much displeasure or disagreement soon found their way to a new home. For instance, before the 1947 season the players met with Hayes to demand an increase in their per diem from $2 to $3. Their spokesman, Lyman Bostock, said to Hayes, “As of now, we’re not askin’ that, but when that time come, we expect to get three dollars.” As Bostock recalled with a sardonic laugh, “Hayes said, ‘Ah, I see Bostock is your spokesman.’ Nobody said nothin’. I got the message. I was traded to Chicago.”13 Toward the end of that season Hayes had a running dispute with manager Tommy Sampson over the way Sampson allocated playing time. After Sampson missed a few games with appendicitis, Hayes docked him $125, which was the end of it for Sampson, who said, “I told him to take his job and stick it.”14 Jim Zapp was insulted when, after the 1948 season, Hayes left him off a barnstorming team that was traveling with the Jackie Robinson All-Stars. In a huff, Zapp asked for his release. Hayes did him one better by essentially blackballing him from the Negro American League for a year.

The Black Barons were strictly an investment for Hayes. He was not a huge baseball fan and his only tenuous connection with the sport had been through a funeral home softball team. Nonetheless, he wanted to see that investment in action from time to time, so he purchased a private plane. Still a novice pilot, Hayes hired a World War II veteran named U.L. Gooch to assist him on his flights.

Gooch would go on to a notable career in aviation and in the Kansas State Senate, but at the time he was a young man looking for a job, and flying around the country with a well-heeled, well-connected fellow like Tom Hayes had its appeal. Gooch recalled that the man knew how to wield his influence. “He was a guy who could call somebody at our destination, and they’d have a suite ready for us at the hotel and also a room for me. Somebody would even meet us at the airport and take us.” Hayes took care of Gooch in other ways, too. “Tom was liberal and liked to have fun. … Just the fact that I was his co-pilot gave me status. Tom would always see that I had a good time, too. Girls always converge on athletes and an even more select group rises up to the management, and my proximity to Tom allowed me to enjoy some companionship. It was an exciting summer.”15

Hayes’s most notable signing was that of Willie Mays, whom he plucked from the Birmingham Industrial League on the recommendation of Piper Davis, at age 17. The two agreed to a contract of $250 per month on July 4, 1948, and Mays became a fixture in the lineup almost immediately.16 As Mays was entering, however, many of the best Negro Leaguers were exiting. Jackie Robinson had broken the color barrier in 1947, and Negro League owners found themselves selling off their most talented players.

Over the next few years Hayes frequently quarreled with major-league owners who he thought were trying to give him the shaft. The ugliest spat pitted Hayes against the New York Yankees in a battle over shortstop Artie Wilson.

Wilson, like Mays, had come out of the Birmingham Industrial League. He signed in 1944 and rapidly earned a reputation as the best shortstop in the Negro Leagues, a smooth defender with great speed who won consecutive batting titles in 1947 and ’48. New York Yankees scout Tom Greenwade approached Wilson about making the jump to Newark, the Yankees’ International League affiliate. Wilson demurred; the money was not right. But Greenwade floated stories in the press which declared that Hayes had agreed to sell Wilson for $10,000 and that the star infielder would be in Newark at the start of the 1949 season.

According to John Klima, author of Willie’s Boys, there is no evidence anywhere that Hayes formally agreed to anything, but the story took on a life of its own. Hayes claimed that Wilson wanted to return to Birmingham rather than make less money in Newark, so that settled it as far as he was concerned. “How do they expect him to sign when no money has been posted or paid?” Hayes said.17

With the sale to the Yankees apparently resolved, Hayes asked Saperstein to broker a deal with Cleveland, which also had expressed interest in Wilson. And what a deal it was. Indians owner Bill Veeck offered the highest amount ever paid for a Negro League player — $10,000 to Hayes and Saperstein plus a $5,000 major-league contract for Wilson. When Wilson found out he exclaimed, “This is the greatest day of my life.”18

But not so fast. The Yankees insisted they had a deal in place with Hayes and asked Commissioner Happy Chandler to intervene. The commissioner’s office launched a slapdash investigation, never bothering to speak to Hayes or Wilson, and subsequently awarded Wilson to the Yankees. New York already had an established shortstop in Phil Rizzuto, so they turned around and sold Wilson at a profit to the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League.

Meanwhile, Hayes had to return $15,000 — representing Wilson’s contract fee and signing bonus — to the Indians. It was money he did not have because he was still waiting for his $10,000 from the Yankees. Chandler’s ruling came down in May. The Yankees failed to send Hayes a check for the Wilson purchase until August 31.

Around this same time, Hayes also was in a state of high dudgeon at James Murray, owner of the Boston Red Sox affiliate in Scranton, whom he suspected of trying to ace him out of $7,500, half the price the Red Sox had agreed to pay for the rights to Piper Davis.19 However, it was the Wilson mess that left Hayes particularly embarrassed and furious. He felt that the Yankees and the major-league establishment had shown him disrespect and he was determined to save face.

Never an easy man to negotiate with, Hayes became nearly impossible, at least as white owners saw it. He insisted on top dollar for his players and insisted on dealing directly with team executives, not just scouts. His players sometimes felt they were sacrificed on the altar of Hayes’s pride. Hayes reportedly shot down more than one solid offer for his ace right-hander, Bill Powell, who grew resentful. “Tom Hayes wouldn’t sell us. We got messed around. I could’ve been in the majors.”20 Pitcher Bill Greason felt Hayes genuinely wanted the best for his players, but business was business. “He was interested in protecting his property,” according to Greason.21

Hayes’s smoldering bitterness toward the Yankees made the prospect of selling Willie Mays to their National League rivals, the New York Giants, particularly appealing. Hayes failed to sign Mays to a contract in 1950, possibly, as author Neil Lanctot speculates, to avoid the burden of a season-long financial commitment in the face of dwindling attendance. New York agreed to pay $10,000 for the rights to the Black Barons star — even though legally the Giants probably didn’t owe Hayes anything. That was certainly the position of Mays’ father. “Why should Mr. Hayes get anything?” he wondered. “I ain’t signed no contract with Mr. Hayes. Willie ain’t signed no contract with Mr. Hayes.”22 However, the way Giants owner Horace Stoneham figured it, $10,000 plus a courteous, respectful telegram — from one successful businessman to another — was worth it to placate the querulous Black Barons owner and reduce the likelihood of a lawsuit.

The exodus of talent to Organized Baseball watered down fan interest and quickly made it in an increasingly hard slog for Negro League owners. Hayes could see as early as 1949 that, as he put it, “[t]he golden era has passed. Teams that are to survive must retrench and proceed with caution.”23 Those Sunday Black Barons games, once almost like a social event, drew increasingly sparse crowds and Hayes had to limit his club’s travel just to make payroll.

By the end of the 1951 season, Hayes had had enough and announced that the Black Barons were for sale. “If some local group in Birmingham would be interested in keeping the team here in Birmingham, they can contact me before I make a move to transfer,” he declared. “I feel that a group of Birmingham owners could make a success of the venture. It has been a profitable one for me up to the present year.”24 He found no takers and put another $2,000 into the club to keep it operating in 1952 before selling it to the owner of the Baltimore Elite Giants, Sou Bridgeforth, who combined the two teams and dissolved the Elite Giants.

Although Hayes ended up justifiably bitter toward the baseball establishment, he was proud of his involvement with the Black Barons and remained on good terms with Saperstein. The men got together in Memphis in 1965, when the Globetrotters were in town, and Saperstein followed up with a warm letter noting, “Would appreciate a periodic note … so that both of us know each other is well.”25 In another note to his old partner, Saperstein looked back fondly on their time together. “They were rough, tough days … but we were young, Tom, and could take most anything. It was a real hard push but there is a real sense of satisfaction in getting a job done.”26

After leaving baseball, Hayes remained a prominent figure in Memphis, not only through his involvement with the funeral home and other businesses but also through his civic duties. He led a drive to install air-conditioning on city buses and served on the Memphis Transit Authority from 1966-70; he was instrumental in the push to hire the first black bus drivers. He was a member of the Metropolitan Baptist Church for 50 years and a longtime trustee. Metropolitan Baptist is located in the heart of a vibrant African-American neighborhood now known as Soulsville USA and which was home to Stax Records, a label whose roster included stars like Otis Redding and Booker T and the MGs.

The church played a key role in the civil-rights movement — it was a home for meetings of the NAACP and hosted Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as a guest speaker. Dr. Reginald Porter, who grew up in the church and later became its pastor, remembers that era as a difficult and terrifying time. “Your neighborhood was a great place but then once you go outside the neighborhood and into white areas or Downtown then it [was] literally dangerous for you.” However, men like Tom Hayes served as a beacon in that darkness. “Having examples of people who have been able to succeed and can encourage you to attempt great things was helpful.”27

Hayes struggled with poor health in his later years. His death from a heart attack in 1982, at the age of 79, was cause for mourning throughout Memphis, particularly in the African-American community. After his sister-in-law died, the funeral home closed its doors and construction crews razed the 111-year-old house in 2011. One community leader said the loss of the historic funeral home demonstrated a “lack of foresight and appreciation for history.”28 However, Hayes’s legacy in his hometown and his impact on baseball history endure.

This biography appears in “Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series” (SABR, 2017), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Green Polonius Hamilton, Beacon Lights of the Race (Memphis: E.H. Clarke & Brother, 1911), 438-443.

2 Suzanne E. Smith, To Serve the Living: Funeral Directors and the African American Way of Death (Boston: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010), 56.

3 Smith, 56-57.

4 Quoted in Vance Lauderdale, “Crews Demolish Hayes Funeral Home — Oldest African-American Business in Memphis,” Memphis Magazine, July 19, 2011, memphismagazine.com/ask-vance/crews-demolish-hayes-funeral-home-oldest-african-american-business-in-memphis/ (accessed October 10, 2016).

5 Program for funeral service for Helen Meadow, Box 1, Folder 9, T.H. Hayes Collection, Memphis Shelby Public Library & Information Center.

6 Wesley Groves, telephone interview with author, November 21, 2016.

7 Helen Hayes Groves, telephone interview with author, November 21, 2016.

8 “Jim Taylor, Manager Black Barons, Here,” undated article, Box 1, Scrapbook 1, Hayes Collection, Memphis Shelby Public Library & Information Center.

9 “Baron’s Bathing Beauty Contest Has Fans All Agog,” Birmingham World, July 19, 1940, Box 1, Scrapbook 1, T.H. Hayes Collection, Memphis Shelby Public Library & Information Center; James Purdy, “Memphis Red Sox Split Twin Bill with Birmingham Barons,” Birmingham World, July 20, 1940, Box 1, Scrapbook 1, T.H. Hayes Collection, Memphis Shelby Public Library & Information Center.

10 John Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball League (Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 1975), 182.

11 Wesley Groves.

12 Charles Einstein, Willie’s Time: Baseball’s Golden Age (Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004), 299.

13 Brent Kelley, Voices from the Negro Leagues: Conversations with 52 Baseball Standouts (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2005), 65.

14 Brent Kelley, The Negro Leagues Revisited: Conversations with 66 More Baseball Heroes (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company 2010), 127.

15 U.L. Gooch, “Rip,” with Glen Sharp, Black Horizons: One Aviator’s Experience in the Post-Tuskegee Era (Wichita, Kansas: Aviation Business Consultants, 2006), 81-82.

16 Copy of Willie Mays Contract, Negro American league of Prof Baseball Clubs Uniform Player Contract, Box 1, Folder 3, T.H. Hayes Collection, Memphis Shelby Public Library & Information Center.

17 John Klima, The 1948 Birmingham Black Barons, The Last Negro League World Series, and the Making of a Baseball Legend (Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley), 228.

18 Ibid.

19 James Murray to Thomas Hayes, August 13, 1949, Box 1, Folder 4, T.H. Hayes Collection, Memphis Shelby Public Library & Information Center; Thomas Hayes to James Murray, August 23, 1949, Box 1, Folder 4, T.H. Hayes Collection, Memphis Shelby Public Library & Information Center.

20 Larry Powell, Black Barons of Birmingham: The South’s Greatest Negro League Team and Its Players (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 152.

21 Klima, 226.

22 Einstein, 303.

23 Quoted in Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 342.

24 “Hayes Gives Up, Puts Black Barons on Sale,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 6, 1951.

25 Abe Saperstein to Thomas Hayes, April 1, 1965, Box 1, Folder 8, T.H. Hayes Collection, Memphis Shelby Public Library & Information Center.

26 Abe Saperstein to Thomas Hayes, April 21, 1965, Box 1, Folder 8, T.H. Hayes Collection, Memphis Shelby Public Library & Information Center.

27 Lance Wiedower, “Metropolitan Baptist Church Has Long Soulsville USA History,” High Ground News, March 9, 2016, highgroundnews.com/features/MetropolitanChurch.aspx (accessed January 18, 2017).

28 David Connolly, “Minister LaSimba Gray Pursues Building for Preserving African-American History,” Memphis Commercial-Appeal, May 15, 2012, commercialappeal.com/news/minister-lasimba-gray-pursues-building-for-preserving-african-american-history-ep-385925924-329410551.html (accessed February 5, 2017).

Full Name

Thomas Henry Hayes

Born

November 20, 1902 at Memphis, TN (US)

Died

, 1982 at Memphis, TN (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.