Dan Bankhead

Until the Negro Leagues were officially recognized as major leagues in December 2020, Dan Bankhead was on record as the first African American to pitch in the majors. He remains best known for that fact, as well as another: he and four brothers all played in the Negro Leagues. However, Bankhead’s big-league career was brief and unsatisfying, and so he received scanty mainstream press coverage. Even the Black newspapers never profiled him in any depth. He also passed away at the young age of 55 in 1976, before Negro Leagues and Brooklyn Dodgers historians could record his personal memories. Fortunately, family and friends helped to connect the dots.

Until the Negro Leagues were officially recognized as major leagues in December 2020, Dan Bankhead was on record as the first African American to pitch in the majors. He remains best known for that fact, as well as another: he and four brothers all played in the Negro Leagues. However, Bankhead’s big-league career was brief and unsatisfying, and so he received scanty mainstream press coverage. Even the Black newspapers never profiled him in any depth. He also passed away at the young age of 55 in 1976, before Negro Leagues and Brooklyn Dodgers historians could record his personal memories. Fortunately, family and friends helped to connect the dots.

These dots were widely scattered – as with many Black ballplayers in his day, Bankhead’s career was multinational. He starred in Puerto Rico, made detours to the Dominican Republic and Canada, and then knocked around Mexico well into his 40s. Always a respectable hitter, Bankhead played the field abroad in addition to pitching. Outside the US, he was also a coach and manager.

Though Bankhead was clearly talented – he drew Bob Feller comparisons – he was hindered by control problems and an old injury. Authors Larry Moffi and Jonathan Kronstadt also pinpointed a crucial problem: “Like many of baseball’s first Black players, he was thrown into white baseball with the physical tools to succeed but little or no emotional support.”1 Jackie Robinson was Bankhead’s roommate when the pitcher first joined the Dodgers, four months after Robinson broke the color barrier. In his biography of Robinson, Arnold Rampersad said it bluntly: “Some observers, including Blacks, thought that [Bankhead] choked in facing white hitters.”2

Negro Leagues star and raconteur Buck O’Neil offered a more nuanced view. Author Joe Posnanski was there for a conversation between Buck and Satchel Paige’s son Robert:

“See, here’s what I always heard. Dan was scared to death that he was going to hit a white boy with a pitch. He thought there might be some sort of riot if he did it. Dan was from Alabama just like your father. But Satchel became a man of the world. Dan was always from Alabama, you know what I mean? He heard all those people calling him names, making those threats, and he was scared. He’d seen Black men get lynched.”3

Also, while Dodgers broadcaster Red Barber described Bankhead as “a quiet, pleasant man,”4 there were other sides of his personality. Sometimes he simply did not act in his own best interest – he lost two jobs abroad under a cloud. His brothers Sam and Garnett Bankhead both died by gunshot following quarrels (aged 70 and 63, no less); Dan too had a temper, which a weakness for women allegedly provoked. His family life was at times tumultuous. Yet as he battled illness and lived hand to mouth in his final years, this man attained peace.

Daniel Robert Bankhead was born on May 3, 1920, in Empire, Alabama. His parents, Garnett Bankhead Sr. and Arie (née Armstrong), had five boys and two girls who lived to adulthood. His given name appears as simply Dan in his military records, in the Social Security system, and on his gravestone. His son William F. Bankhead believed that his father shortened it at some point.

The town of Empire is a little more than 30 miles northwest of Alabama’s largest city, Birmingham. It is in the coal country that fueled Birmingham’s steel industry. Garnett Sr., who had worked for a lumber company around the time of World War I, labored in coal. The 1920 census shows him on the crew of a coal tipple (or loading facility); the 1930 census lists him as a miner. The sawmills, lumber yards, and mines were all hard and dangerous jobs – but they offered steady pay and a step up from sharecropping for many African Americans. The shadow of Jim Crow then loomed over the Deep South.

Garnett also played baseball. Although the source of the anecdote is not clear, Moffi and Kronstadt wrote that “he was a star first baseman in the Cotton Belt League until the day he saw a man die after being hit by a flying bat.”5

Dan was the third of the five ballplaying Bankhead brothers. The eldest, Sam, was a top-notch Negro Leaguer: a speedy, versatile, good-hitting infielder-outfielder from 1930 through 1950. A hardnosed leader on the field, Sam became a manager late in his career. While still playing shortstop, he was skipper of the Vargas Sabios (Wise Men), champion of the Venezuelan winter league in 1946-47. Sam then led the Homestead Grays during their last two years as an independent club (1949-50). He also managed Farnham in Canada’s Provincial League in 1951 and is recognized as the first Black skipper of a predominantly white team. Negro Leagues author John Holway contended that Sam inspired Troy Maxson, the lead character in August Wilson’s award-winning play Fences.

The second brother, Fred, was an infielder from 1936 through 1948. Joe and Garnett Jr. were both pitchers. Joe was with the Birmingham Black Barons in 1948, while Garnett pitched briefly with the Memphis Red Sox in 1947 and spent some time with the Homestead Grays in 1948 and 1949. (Another brother, James, born roughly two years before Dan, apparently died young. He appeared in the 1920 census but not in 1930.)

Bankhead attended public schools in Birmingham. In 1940, he became a pro ballplayer with the Black Barons. In a talk with author Brent Kelley, William “Jimmy” Barnes, another young local player who went to the Negro Leagues, recalled how it happened (though his memory was slightly off on the year and the team that signed Bankhead). “I just tried out for a little city league team. Dan Bankhead and I were trying out for third base and we were throwing the ball across the infield so hard.”6

Kelley also heard from another of Bankhead’s contemporaries, Barons infielder Ulysses Redd. “We went to spring training and had a bunch of guys out there – a bunch of shortstops anyway. . . .even Dan Bankhead wanted to be a shortstop at that time, but he was throwin’ so hard they said they would make a pitcher outta him. They did the right thing.”7 Seamheads.com shows a pitching record of 4-1 for Bankhead in 1940 and 7-1 the next year. He pitched two scoreless innings in the East-West All-Star Game, on July 27, 1941.

In the winter of 1941-42, Bankhead went to play ball in Puerto Rico for the first time. The Puerto Rican Winter League was in its fourth season, and a host of great Negro Leaguers were there, most notably Josh Gibson (Santurce) and Willard Brown (Humacao-Arecibo). Sam Bankhead was with Ponce, but Dan was a member of the Mayagüez Indios, who also featured Willie Wells and Buster Clarkson. He won 7 and lost 8.

Returning to the Black Barons in 1942, Bankhead posted a known record of 2-1. After that, though, the young man decided to serve his nation amid World War II. On April 22, 1943, he enlisted in the Marine Corps in Macon, Georgia. He was stationed at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. The Montford Point Marines, as they were also known, were not a combat unit. Even so, the all-Black troops became historically significant as an important step toward the integration of American military forces. Bankhead was part of the Montford Point baseball team, which remained in the States for the duration of the war and toured as a “morale raiser.” In addition to pitching, he played shortstop and the outfield.8

Returning to the Black Barons in 1942, Bankhead posted a known record of 2-1. After that, though, the young man decided to serve his nation amid World War II. On April 22, 1943, he enlisted in the Marine Corps in Macon, Georgia. He was stationed at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. The Montford Point Marines, as they were also known, were not a combat unit. Even so, the all-Black troops became historically significant as an important step toward the integration of American military forces. Bankhead was part of the Montford Point baseball team, which remained in the States for the duration of the war and toured as a “morale raiser.” In addition to pitching, he played shortstop and the outfield.8

The Marine got occasional leave to pitch for the Black Barons, appearing at least once in 1943 and twice in 1944. On June 5, 1944, the New York Times reported that Bankhead struck out 17 New York Black Yankees as he fired a three-hit shutout in the nightcap of a doubleheader. In the opener, the Barons blanked the Philadelphia Stars 9-0. The twin bill took place at Yankee Stadium before an estimated crowd of 12,000.9

Bankhead, who had gained sergeant’s rank, was released from the service on June 7, 1946. He re-entered baseball with the Memphis Red Sox of the Negro American League. He once again made the roster for the East-West All-Star Game – in fact, a pair of them were held that year. He started the first game, on August 15, allowing two earned runs in three innings with no decision. Three days later, he got the win for the West with three scoreless innings.

According to The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues, Bankhead finished the year with a 7-3 record, far outshining his 24-36 team. His 42 strikeouts led the league, though this seemingly low number, like his won-lost records, likely reflects patchy data (Seamheads shows even lower totals).

Sometime in the mid-1940s (the exact date remains under investigation), Bankhead got married to Linda Marquette, who had gone to school in Kansas City and also attended the Chicago Conservatory of Music. According to his son William, they met while she was performing as a jazz singer. The couple had a daughter named Waillulliah, or Lulu for short. The young girl’s name was patterned after famous actress Tallulah Bankhead – a member of a prominent Alabama family. Tallulah may have been linked to the Black Bankheads, because her great-grandfather owned slaves in Lamar County, about 80 miles west of Empire.

William Bankhead came to believe that Lulu was actually a foster child, and there is reason to believe him. A 1947 article in the Richmond Afro-American noted that the young girl was nine years old and that her parents had been married for 10 years.10 But that means Dan and Linda would have been about 17 and 15, respectively, upon their wedding. This is at odds with the evidence and suggests a vague effort at propriety in the article.

With Linda and Lulu in tow11, Bankhead returned to Puerto Rico in the winter of 1946-47. Pitching for the Caguas Criollos, he went 12-8 and led the league with 179 strikeouts. He also showed his speed on the basepaths with 12 steals.

Back with Memphis in 1947, Bankhead had the pleasure of playing with his brother Fred. That year was the first time that any of the Bankhead men were teammates; Garnett also appeared briefly with the Red Sox in ’47, possibly after Dan left. On July 27, Dan again got the win in the East-West All-Star Game, allowing one run in three innings at Comiskey Park. The West won, 5-2, before a crowd of 48,112.

Dodgers scouts George Sisler and Wid Matthews were aware, and they alerted their boss, Branch Rickey. Brooklyn was short on pitching – ironically, they had unloaded starter Kirby Higbe because he refused to play with Jackie Robinson – so Rickey again turned to the Negro Leagues. On August 22, as Rickey biographer Lee Lowenfish wrote, “he and Sisler then traveled to Memphis to observe Dan Bankhead. . . . After the game [in which he struck out 11 and lifted his record to 11-512], Bankhead and his wife fed the visitors dinner, and soon thereafter Rickey announced that the pitcher had been purchased from Blue Sox [sic] owner J.B. Martin for $15,000.”13

The Richmond Afro-American carried a picture of Dr. Martin’s brother B.B. (a co-owner and also a dentist) shaking hands with Linda Bankhead after the deal was announced. The slender, graceful woman (who was not African American) was noted as a former featured singer with jazz great Fletcher Henderson’s orchestra. She and Lulu – along with a dog named Tackie and a pet chicken named Fannie Chee-Chee – would join Bankhead in Brooklyn in early September. Linda said she was only a baseball fan when her husband was pitching.14

Lowenfish continued, “Rickey was happy that Dan Bankhead’s color did not attract overwhelming press attention when the pitcher arrived in Brooklyn. The executive always hoped for the day when merit, and not color of skin, determined a person’s chance for success.”15 However, author Jules Tygiel differed, writing that “[Bankhead] received a terrific workout from photographers and newshounds.”16

Rickey would have preferred to test his new pitcher in the minors first, but he needed a live arm more. The 27-year-old’s NL debut came at Ebbets Field on August 26. One news story estimated that Black fans made up roughly a third of that day’s crowd of 24,069.17. A very nervous Bankhead entered in the second inning in relief of Hal Gregg.

The new Dodger allowed eight runs (all earned) on 10 hits in his 3⅓ innings of work that day. In one of his well-honed turns of phrase, sportswriter Red Smith wrote, “(T)he Pirates launched Bankhead by breaking a Louisville Slugger over his prow.”18 However, the hurler displayed his all-around ability by homering off Pittsburgh’s Fritz Ostermueller in his first NL at-bat.

After the game, Bankhead told pioneer Black sportswriter Sam Lacy, “I think I’ll be okay as soon as this newness wears off. Today it seemed like I was wearing a new glove, new shoes, new hat, everything seemed tight.”19

Dodgers manager Burt Shotton mixed praise (“speed, a good curve, and control”) and criticism (“the boys were calling all his pitches”) in his post-game remarks. He said he “wanted another look before I form an opinion one way or another.”20 Bankhead pitched just three times more over the remainder of the season, though, with no decisions and a 7.20 ERA in 10 innings overall. Nonetheless, he remained on the Dodgers roster for the World Series. He made one appearance as a pinch-runner in Game Six. Bobby Bragan had doubled off the Yankees’ Joe Page to score Carl Furillo and put the Dodgers up 6-5. The future big-league manager recalled what happened next:

“Bankhead would have scored from second a few pitches later when Eddie Stanky singled to right but Dan fell down rounding third and just scrambled back to the bag in time. When Pee Wee Reese singled to center both Dan and Eddie scored to ice the game.”21 (Not quite – it took Al Gionfriddo’s famous catch off Joe DiMaggio to hold the lead.)

In the spring of 1948, the Dodgers trained in the Dominican Republic. It marked the first time that Black and white ballplayers stayed at the same hotel. This was a refreshing experience for Jackie Robinson and Bankhead, not only because of the good treatment at the classy Hotel Jaragua but also thanks to the fans. Robinson said, “They show it every time Dan Bankhead or I walk on the field by cheering and clapping as enthusiastically as if we were one of their native players.”22

News service stories from what was then Ciudad Trujillo stated that Bankhead “was converted into a gardener [outfielder] because of his batting power and speed afoot.”23 The experiment was abandoned, though – the Dodgers assigned Bankhead to their Class B affiliate in Nashua, New Hampshire, and he concentrated on pitching. On July 25, he fired a seven-inning no-hitter against the Springfield Cubs. He blazed his way to a 20-6, 2.35 record with a league-leading 243 strikeouts. His wins also led the New England League, and he barely missed the Triple Crown of pitching, with his ERA behind only Harry Schaeffer’s 2.33.

On August 22, newspapers reported Bankhead’s promotion to St. Paul, the Dodgers’ Triple-A affiliate in the American Association. Two days later, Lula Garrett of the Baltimore Afro-American wrote, “Satchel Paige opines that Dan Bankhead, youngest [sic] member of the Bankhead Baseball Brothers, throws a faster ball than Cleveland’s Bobby Feller.”24 He finished the season in good form, going 4-0 for the Saints with a 3.60 ERA.

Bankhead rejoined Caguas that winter, posting a 9-8 record. In 1949, he was assigned to Brooklyn’s other Triple-A team, the Montreal Royals. Again he won 20 and lost just six, while leading the league in strikeouts (176). Bankhead also led in walks with 170, though, earning the label “Wild Man of the International League.” The bases on balls were no doubt what pumped his ERA up to 3.76. In addition, he batted .323 with a homer and 26 RBIs.

The third-place Royals swept Rochester in the first round of the playoffs and then took four of five from Buffalo to become IL champs. Bankhead won the opener against the Red Wings and the clincher against the Bisons. Despite a sore arm, he added another win in the Little World Series, which the American Association champ, Indianapolis, won, four games to two.

In the winter of 1949-50, after barnstorming in the Southwest with a group of Black players led by Luke Easter, Bankhead was back in Puerto Rico again. He led the Puerto Rican Winter League in strikeouts for the second time, with 131. In addition to his 10-8 record, he hit seven homers. Caguas won the league championship and thus represented Puerto Rico in the second Caribbean Series, which was played in February at Sixto Escobar Stadium in San Juan.

In the second game of the four-team round robin, Bankhead faced ageless veteran Conrado Marrero, the ace of heavily favored Cuba’s staff. Puerto Rico gave Bankhead one run in the second inning, but that was all he needed as he threw a shutout. However, he lost two games to the eventual champion, Panama, including the tiebreaker.

Before the 1950 season opened, Bankhead was the subject of an uncomplimentary story quoting Branch Rickey. Allegedly the Mahatma turned down “a flattering offer from the Braves for the big right-hander. He confidentially told [Boston co-owner] Lou Perini that Bankhead wouldn’t help the Boston club.”25 The Bankhead-to-Boston rumor had been swirling since the prior fall; Rickey had also offered to deal the pitcher that winter to the White Sox.

Still, Bankhead won a job with Brooklyn that spring. He proceeded to get all nine of his NL wins with the Dodgers. His first came in relief of Don Newcombe at the Polo Grounds on April 28. Bankhead took his first four decisions, going all the way versus the Cubs at Ebbets Field on May 24. On June 18, he shut out the Cardinals on six hits at home.

Just when Bankhead looked to be settling in as an important member of the rotation, though, arm problems worsened. On July 8, the New York Times reported, “Dan Bankhead’s trouble is serious and may call for surgery. The Negro has considerable calcification in his shoulder.”26 The shoulder had pained him earlier that season too. He had complained of soreness in his first start on May 4. The root cause was apparently a dislocation suffered at the age of 17.27

Bankhead’s last start that year came on July 31, but he continued to work frequently out of the bullpen. He finished the year with a record of 9-4, 5.50, starting 12 times in 41 appearances. Control was a problem, as he walked 88 in 129⅓ innings.

In the winter of 1950-51, the Bankheads were in the Dominican Republic, where they welcomed son William that March. William stated that Bankhead was playing with the Escogido Leones, one of the four long-running Dominican clubs, a year before professional ball resumed in the country.

Bankhead’s arm really ailed him in 1951. He pitched a total of just 14 innings in seven games for the Dodgers (0-1, 15.43). In his last two appearances, he was shelled for 14 runs and 16 hits in seven innings. On July 24, Brooklyn announced that it had sold his contract to Montreal and brought up Clem Labine from St. Paul to replace him. Bankhead never made it back to the majors. Perhaps his most lasting big-league moment came amid a clubhouse debate, as he imparted a piece of down-home wisdom to his one-time roommate. “Not only are you wrong, Robinson,” said Bankhead, “You are loud wrong.”28

The pitcher offered another reason for his performance in Brooklyn – “financial pressure brought on by an inability to find an apartment that would accept children. He and his family stayed at an expensive hotel suite, which ate up most of his salary. ‘Nobody with an apartment would let me bring in my kids,’ he said. ‘Nobody wanted them. But I did.’”29

Things were not a whole lot better with the Royals. It took Bankhead over a month to pick up his first win in the International League, and he finished at 2-6, 3.91, mainly in relief. He saw some action out of the pen in the playoffs – Montreal again won the pennant – plus two more brief outings as the Milwaukee Brewers took the Little World Series in six games.

Bankhead resumed his Puerto Rican career in 1951-52 with a new club, the Santurce Cangrejeros (Crabbers). His record was 7-1, with a 3.71 ERA – although he had just 40 strikeouts in 70 innings, showing that he was no longer getting batters out with heat. Still, he was “unbeatable down the stretch” as the Crabbers won 16 of their last 20 games to make the playoffs before losing the finals to San Juan.30

Bankhead returned to Montreal for the 1952 season. However, the Dodgers organization released him in July, with a record of 0-1, 6.92. “Plagued with arm trouble, he worked only 13 innings in five games this season.”31 Bankhead then went back to Escogido – the Dominican baseball season was held in the summer from 1951 through 1954 – but he did not last long there.

In August, he had been named the club’s manager, replacing Félix “Fellé” Delgado, who had gone to the US to scout talent. Against the Estrellas Elefantes, Bankhead was trying for his first win against three losses when an aggressive baserunning play backfired. The third baseman had thrown a live ball to the ground arguing with the umpire, who had called Bankhead safe at third. Bankhead broke for the plate, slid in hard, but was out.

“[Catcher Zoilo] Rosario, fuming . . . immediately fired the ball at the Negro pitcher as he headed towards the Lions’ bench, but his aim was inaccurate and he missed. However, Bankhead quickly whirled around, picked up the catcher’s mask and hit Rosario over the head with it, opening a gash that required three stitches. In the free-for-all that followed, Bankhead was knocked out cold. After peace was restored, Rosario and Bankhead were fined and jailed.”32

Later that month, Bankhead was fired for “breaking training, fraternizing with players of another team and failing to show up for practice,” according to club president Paco Martínez Alba (Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo’s brother-in-law). Perhaps a more telling factor was that “the club had been having financial squabbles” with Bankhead.33 This man was always known as a tough negotiator, going back to his Negro League days.

In 1953, Bankhead played for Drummondville in the Canadian Provincial League. Quite a few Black ballplayers were in this league, including (though briefly) Bankhead’s younger brother Garnett. A few big-leaguers were there too, including player-manager Al Gionfriddo, Bankhead’s teammate on the ’47 Dodgers and with Montreal in ’49 and ‘’51. (Gionfriddo’s distinct memory of Bankhead was the way he used to “stamp the hell out of the rubber when he pitched.”34) With the last-place Royals, Bankhead’s batting line was .275-3-28; he pitched a handful of games at most (0-0, 0.00).

Late that July, Drummondville dumped veterans whose salaries were too high for the team’s modest budget.35 Bankhead went to Mexico, where he would spend nearly all of his remaining 13 years in the game. He served mainly in the field for the Monterrey Sultanes (.281-3-12) in 1953, though he also went 1-0, 2.90 in two games as a pitcher, including a complete game.

In the winter of 1953-54, Bankhead played in Mexico’s Liga de la Costa del Pacífico, which was entering its ninth season. His team was the Jalisco Charros, also known by the state’s capital, Guadalajara. Bankhead batted .335 as the first baseman and went 7-5 on the mound. He was named to the All-Star team for the league’s Southern division; that game took place on January 13, 1954. Joining him was Charros catcher Sam Hairston, patriarch of a three-generation big-league family.36

Bankhead stayed in Monterrey for the 1954 season (.273-7-33/2-2, 5.56 in seven pitching appearances). In 1955, the Mexican League entered Organized Baseball at the Double-A level. Bankhead split the season between the Sultanes and Veracruz Águila (combined totals: .316-9-46/0-1, 9.00). In 1956, he again played with two teams, Veracruz and the Mexico City Tigres (combined totals: .288-4-28/1-0, 3.00 in just 6 innings pitched).

In 1957, Bankhead took a step down to the Class C Central Mexican League. With the Aguascalientes Tigres, whose roster also included future Duke University athletic director Tom Butters, he batted .361 with 4 homers and 52 RBIs. He also went 2-2, 6.30 on the mound; Estadio Alberto Romo Chávez was and is a hitter’s ballpark. Butters recalled that the air was thin – Aguascalientes is 6,184 feet above sea level.

There was a gap in Bankhead’s summer career in 1958. William Bankhead remembered seeing his father arrested in Brooklyn that year after a stormy domestic dispute. To the best of William’s knowledge, though, Bankhead and Linda (who died in 2007) never got divorced. Throughout the years in Mexico, “he used to come home and make pit stops.”

Bankhead resumed play that winter with the Puebla Pericos (Parrots) in Mexico’s Veracruz League. He turned up in assorted stories in The Sporting News; little head shots showed he was still a “name.” The Parrots were the league champion, with Bankhead playing first base and pitching. In the spring of 1959, he returned to Veracruz as a player-coach, which likely explains his limited action (.244-0-6/0-0, 0.00).

A relatively stable period of four summers in Puebla then followed; the Parrots franchise was by then in the Mexican League. Bankhead was largely a reserve and pinch-hitter as he entered his 40s. During this time, he appeared in 225 games but amassed only 358 at-bats, with a grand total of one homer and 34 RBIs. His average was .293, driven largely by his .378 mark in 1960 (31-for-82). As a pitcher, his composite record was 24-15, 4.60 – mainly in relief, as he started just six times and pitched just 272 innings across 133 appearances.

In 1960 and 1961, Bankhead’s name occasionally popped up in the American papers, especially in San Antonio. During these two years, the Mexican League teams faced Texas League opponents regularly – 36 games and 24 games for each Mexican League club. The combined leagues were known as the Pan American Association. In August 1961, Bankhead won three games in two days in relief. That fall saw him with Saltillo in the little-known Northern Autumn League, which apparently lasted only one season despite drawing decent crowds thanks to pitchers like Luis Tiant.

Bankhead then wintered with another obscure Mexican circuit, the Bajío (Lowlands) League. He managed the Acámbaro Trains, a club in the state of Guanajuato. Bankhead must have inspired a following, for 100 fans traveled 500 miles to Puebla in August 1962 to cheer for him on Dan Bankhead Day in Puebla. The veteran pitched a complete game and won 13-1, as Alonzo Perry (another ex-Negro Leaguer, then 39) scored Monterrey’s only run on a wild pitch.37

To start the 1962 winter season, Bankhead was manager of Martínez de la Torre in the Veracruz League – but he was fired on November 14. The club was 6-4; there was only a cryptic report saying, “The Sugar Canes’ officials . . . took the action ‘for the good of the club.’”38 So then, after 10 seasons away, he resurfaced in Puerto Rico as a player-coach. He was 3-0 pitching for Caguas, winning both ends of a doubleheader in relief on December 2. A week later, Bankhead was named the club’s interim manager after Preston Gómez resigned on December 9.39 Within three days, though, the Criollos released him and made Jim Rivera manager. Bankhead then joined the Ponce Leones.40

William Bankhead went to the island that winter too. He had fond memories of how his father provided him with a white horse to ride. “I used to ride up into the hills there and shoot at iguanas with a Daisy BB gun,” he said. William recalled that Bankhead left the club after another domestic dispute with Linda. A Criollos teammate, pitcher Julio Navarro, said, “I can’t say whether it did or didn’t happen – I don’t remember anything like that. But he did a hell of a job pitching for an older guy. You tell me he was 42, I thought he was in his 50s.

“He was a good person, but I think he didn’t have much experience managing. Also, our team didn’t look like it had a chance to make the playoffs that year. Just before Christmas, some guys who aren’t from Puerto Rico want to go home, so teams will release them if they’re not winning. It’s also the last date to give them a chance to sign with somebody else.” However, the post-Bankhead Criollos won 24 of their last 32 games, surged from fifth place to second (out of six teams), and made it to the playoff finals.

After his last season with Puebla – he brought along a couple of Puerto Ricans he’d scouted41 – Bankhead moved to the Mexican Central League (Class A) in 1964. With the León Broncos, he put up a remarkable average of .441 with 4 homers and 41 RBIs, while still pitching capably (4-1, 4.20). He was listed as manager for part of that year, along with Cuban Santos Amaro, father of Rubén Amaro and grandfather of Ruben Amaro Jr.

In 1965, Bankhead remained as nonplaying manager of the León ballclub, which then became known as the Diablos Verdes (Green Devils). He led them to a second-place finish. At age 46 in 1966, Bankhead then enjoyed his last hurrah as a player with Reynosa. On June 2, the Broncos hired him away – as manager – from Aguascalientes in the Central League. In 11 games, he went 6-for-14, also posting his last pitching win on July 17. He was 1-0, 4.73 in 19 innings across six relief outings.

Bankhead’s time in baseball then came to an end. Like many men in this position, he really didn’t have another good career option – the game was his life. Much insight on the ensuing period came from Cornelius “Doc” Settles, whose mother, Martha Ann, and aunts Charlene and Essie grew up with Bankhead in Alabama. These good neighbors offered a helping hand.

“It would have been in the mid to late ’60s,” said Settles. “From what I understand, everything started to implode for Dan in Mexico.” William Bankhead stated, “He was pitching more than balls, you know what I mean? Too many kids, too many intimacies. There are several kids down in Mexico that I know of. And you can’t live in a foreign country without money.”

“The nearest oasis was Houston,” Settles continued. “My mom and her sisters weren’t looking for anything. This was just somebody close from home – there was a connection by marriage in there too.

“Dan was facing inner turmoil when he first came to Houston. He was trying to get back on his feet. But he stepped in right when I needed somebody in my life. He was so humble, and he had a down-home sensibility that grounded him. I was just a teenager, and he was always willing to share a few moments with me and my brothers tossing baseballs and playing games. I will never forget Dan Bankhead burning up my hand while trying to catch one of his pitches. Even in his final days Dan could still toss a mean fast ball.

“Dan was facing inner turmoil when he first came to Houston. He was trying to get back on his feet. But he stepped in right when I needed somebody in my life. He was so humble, and he had a down-home sensibility that grounded him. I was just a teenager, and he was always willing to share a few moments with me and my brothers tossing baseballs and playing games. I will never forget Dan Bankhead burning up my hand while trying to catch one of his pitches. Even in his final days Dan could still toss a mean fast ball.

“There’s a photo in Rachel Robinson’s book called An Intimate Portrait on page 92. Jackie is playing cards with Don Newcombe, Campy [Roy Campanella], and Dan. I remember firsthand that Dan also loved playing cards and checkers. He wouldn’t take any prisoners! He would beat us kids in games and laugh afterwards with that sparkle in his eyes and big smile.

“I only wish that I could have grasped who we were hanging out with. I would have done a better job of absorbing every little tidbit. Back then I was too naïve to understand. He would talk about Mexico and the league, how hot it was. He was so fluent in Spanish – he looked Hispanic. His pigmentation was light, and as he got older, he got even lighter. [Note: Garnett Bankhead was listed as a mulatto, as were his sons, in the 1920 census.

“There was a woman living in Mexico too. I just remember vaguely, I don’t remember her name or their child’s, but I met them. She was beautiful. Dan never went into detail about it, though.

“Dan spent his final years working for a small service company delivering food goods and supplies to small businesses and restaurants across Houston. I remember driving over and picking up Dan from his tiny rented apartment that was located upstairs over a garage in Kashmere Gardens, just 10 minutes from our house. He’d have a glove and ball, and he’d be smoking a Camel.”

At some point in the 1970s, Bankhead was diagnosed with lung cancer, and he was in and out of the Veterans Administration hospital in Houston. “His little smoking habit finally caught up with him,” said Doc Settles. “I always thought he’d go back to Mexico, but then he got sicker. You could see him erode. He’d have his ups and downs, but he knew. He just got more and more humble. He was resolved to make peace. Dan’s final days living in Houston were filled with reflection, days of happiness.” Eventually, he succumbed on May 2, 1976 – a day short of his 56th birthday.42

Thanks to the VA, the old Marine was buried under a modest bronze marker in Houston National Cemetery. “I don’t remember if any of his old teammates came to the funeral,” Settles said. “It was a small and quiet event. I don’t think he was in touch with them. It was in the past and he didn’t dwell on it.”

Bankhead’s name surfaced in 2006 in a dispute between his sons William and Dan Herbert Bankhead (born in 1949, later known as Dan Al-Mateen) over the pitcher’s memorabilia. William alleged that the items came into the possession of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum by improper means. A legal battle ensued.43

The less said of this episode, however, the better. It’s best to remember Dan Bankhead as a talented player, a pioneer, and for the goodness in him. William Bankhead remembered once coming to blows with his father, on the street in front of Linda’s residence in Brooklyn Heights. Yet later, before the younger man went to serve in Vietnam in 1971, Dan said “I am sorry,” giving his son a kiss. He bequeathed William the Smith & Wesson pistol he got upon enlisting in the Marines. William also remembered how his father taught him to love and respect animals, birds, and other children.

Doc Settles summed it up nicely too. “He had a personality you wanted to be around. He left you with positive things. I was able to enjoy his laughter and his jokes and his smiles. I just wish we knew more about what he went through as an African American baseball trailblazer.”

Acknowledgments

This biography was originally published in 2009. An abridged version was published in The Team That Forever Changed Baseball and America: The 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers (University of Nebraska Press, 2012). This updated version was published in 2024.

Special thanks for their memories to Doc Settles (e-mail exchanges and phone discussions starting in June 2008) and William F. Bankhead (e-mail exchanges and phone discussions starting in September 2008).

Continued thanks also to Julio Navarro (telephone interview, 2008) and SABR member Jorge Colón Delgado (additional Puerto Rican statistics).

Image credits

Dodgers headshot: courtesy of walteromalley.com

Marines headshot: courtesy of www.mpma28.com

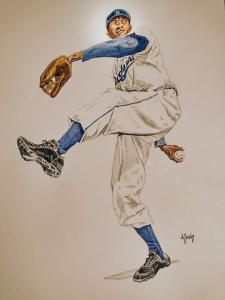

Watercolor: courtesy of Doc Settles, Artist

Sources

Obituary: “Dan Bankhead, 54 [sic], Ex-Dodger, Is Dead.” New York Times, May 7, 1976: 95. Note that The Sporting News sometimes presented Bankhead’s year of birth as 1921.

Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 1997).

José A. Crescioni Benítez, El Béisbol Profesional Boricua (San Juan, Puerto Rico: Aurora Comunicación Integral, Inc., 1997).

Pedro Treto Cisneros, editor, Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano (Mexico City, Mexico: Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V., 1998).

James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994).

John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House Publishers, 2001).

Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2001.

Professional Baseball Player Database V6.0

www.paperofrecord.com (various small pieces of information from The Sporting News and El Informador)

www.ancestry.com (census information on Garnett Bankhead)

www.findagrave.com

Social Security Death Index

Notes

1 Larry Moffi and Jonathan Kronstadt, Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers 1947-1959 (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1994), 13.

2 Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Ballantine Publishing Group, 1997), 184.

3 Joe Posnanski, The Soul of Baseball: A Road Trip Through Buck O’Neil’s America (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2007), 144.

4 Red Barber, 1947: When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1982), 280.

5 Moffi and Kronstadt, 11.

6 Brent Kelley, The Negro Leagues Revisited (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2000), 89.

7 Kelley, 118.

8 From the online history of the Montford Point Marines, webmaster James Stewart Jr.: http://www.mpma28.com/newsletters/newsletter/2854121/44177.htm

9 “Barons Win by 9-0, 13-0; Triumph Over the Philadelphia Stars and Black Yankees,” New York Times, June 5, 1944: 12.

10 “Wife, Daughter, Dog, Chicken Root for Dan,” Richmond Afro-American, September 6, 1947: 1.

11 Leslie Heaphy, The Negro Leagues, 1869-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2002), 173. See also note 10.

12 Dave Bloom, “Beale Street’s Dancing Over Its Boy, Dan,” The Sporting News, September 3, 1947: 7. Seamheads shows a record of 2-1.

13 Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 433. Two notes: the won-lost record cited here and in The Sporting News conflicts with the 4-4 mark shown in The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues. Also, Bankhead’s wife is referred to as “Charlotte.”

14 “Wife, Daughter, Dog, Chicken Root for Dan.”

15 Lowenfish, Branch Rickey, 433.

16 Jules Tygiel, in Sport and the Color Line: Black Athletes and Race Relations in Twentieth Century America, editors Patrick Miller and David Wiggins (New York: Routledge, 2004), 184.

17 “Bucs Win; Bankhead Homers,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 27, 1947: 24.

18 Red Smith, “Views of Sport,” New York Herald-Tribune; date uncertain. Reprinted in Baltimore Afro-American, September 6, 1947: 13.

19 Sam Lacy, “Bankhead Knocked Out in First Dodger Game,” Richmond Afro-American, August 30, 1947: 14.

20 Joe Reichler (Associated Press), “Negro Hurler to Get New Chance,” August 27, 1947.

21 Bobby Bragan, “Bragan Recalls Series Hit,” Evening Standard (Uniontown, Pennsylvania), July 10, 1965: 7.

22 Michael E. Lomax, in Race and Sport: The Struggle for Equality On and Off the Field, ed. Charles K. Ross (Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2006), 66. Originally in New Jersey Afro American and Pittsburgh Courier, March 13, 1948.

23 Leo H. Petersen, “Youth, Speed and Fight To Mark 1948 Dodger Team,” Lima (Ohio) News, March 29, 1948: 11.

24 Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (New York: Fireside, 2004), 125.

25 “Branch Rickey May Be Forced to Eat Words.” Syracuse Herald-American, March 19, 1950: D1.

26 Roscoe McGowen, “Simmons Checks Brooklyn, 7-2, Behind 4-Run Onslaught in Sixth,” New York Times, July 8, 1950.

27 Moffi and Kronstadt, 12.

28 Dave Anderson, “Nice Wrong Isn’t Really So Terrible,” New York Times, February 27, 1998.

29 Anderson, “Nice Wrong Isn’t Really So Terrible.”

30 Thomas E. Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1999, 38.

31 Charleston (West Virginia) Gazette, July 20, 1952: 29.

32 Alejandro Martínez, “Dan Bankhead Fined, Jailed in Dominican Republic Riot,” The Sporting News, August 13, 1952: 30.

33 Alejandro Martínez, “Bankhead Fired as Manager in Dominican Loop,” The Sporting News, September 3, 1952: 32.

34 Peter Golenbock, Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers (New York: McGraw-Hill/Contemporary, 2000 edition), 157.

35 Scott Baillie, “Happy Once Again: Al Gionfriddo Now Playing for Ventura,” Daily Review (Hayward, California), May 20, 1954: 10.

36 Manuel de Jesús Sortillón Valenzuela, www.historiadehermosillo.com/BASEBALL/Menuff.htm (online history of Mexico’s Liga de la Costa del Pacífico). One may also find pictures of and stories about Bankhead and Sam Hairston in the Guadalajara newspaper El Informador.

37 “Bankhead Stars on Big Day,” The Sporting News, August 18, 1962: 39.

38 Roberto Hernández, “Bankhead Fired as Manager; Pinkston Fractures Arm,” The Sporting News, December 1, 1962: 41.

39 Miguel Frau, “Orsino Steps High as Candidate for Triple-Title King,” The Sporting News, December 22, 1962: 29.

40 Miguel Frau, “New Skipper Rivera Spurs Caguas to Winning Splurge,” The Sporting News, December 29, 1962: 33.

41 Roberto Hernández, “Season Opens First in Mexico; Sultans Favored to Repeat,” The Sporting News, April 13, 1963: 48.

42 “Bankhead Dies,” Charleston (West Virginia) Daily Mail, May 7, 1976: 29. Of interest in this story is a reference to a wife coming up from Mexico.

43 Charles Emerick, “Negro Leagues museum brought into family feud, lawsuit over memorabilia,” Daily Record (St. Louis, Missouri), October 3, 2006.

Full Name

Daniel Robert Bankhead

Born

May 3, 1920 at Empire, AL (USA)

Died

May 2, 1976 at Houston, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.