Art Pennington

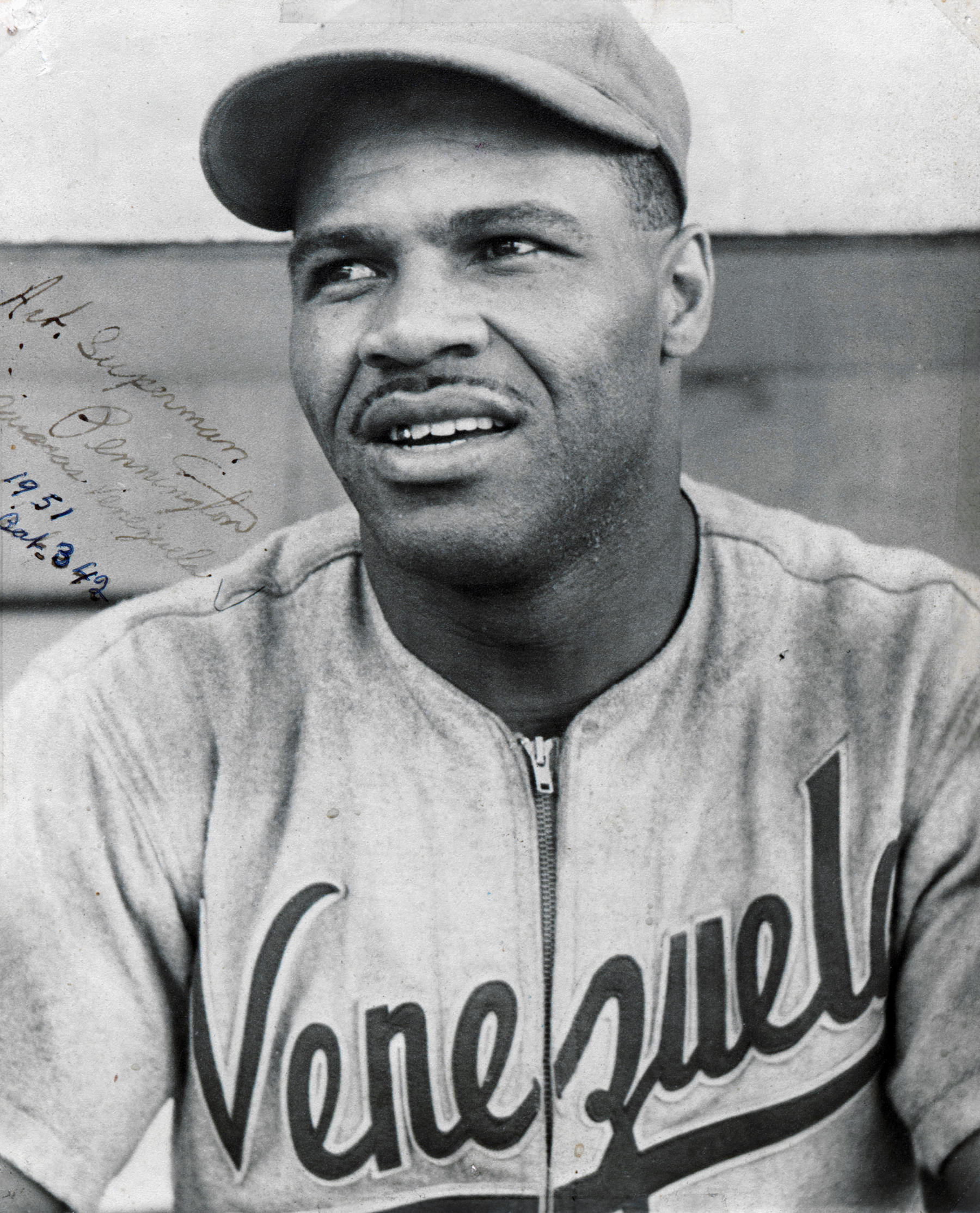

The story is almost apocryphal, existing somewhere on that boundary between real and remembered. As it is most often told, a 10- (or perhaps 11-) year-old Art Pennington was on an afternoon fishing trip with his mother. As they began the trip home, one of the Essex’s balloon tires went flat. Art hopped out of the car and surveyed the situation. He gathered some rocks and told his mother to shove them under the axle when he lifted the car. The boy put his back to the car, gripped the two best points he could reach, lifted part of the 2,000+ pound vehicle so that his mother could shove the jury-rigged jack into place. After that, Art’s mother, Fannie, called him “my little Superman.”1 The name stuck to Art for the rest of his life.

The story is almost apocryphal, existing somewhere on that boundary between real and remembered. As it is most often told, a 10- (or perhaps 11-) year-old Art Pennington was on an afternoon fishing trip with his mother. As they began the trip home, one of the Essex’s balloon tires went flat. Art hopped out of the car and surveyed the situation. He gathered some rocks and told his mother to shove them under the axle when he lifted the car. The boy put his back to the car, gripped the two best points he could reach, lifted part of the 2,000+ pound vehicle so that his mother could shove the jury-rigged jack into place. After that, Art’s mother, Fannie, called him “my little Superman.”1 The name stuck to Art for the rest of his life.

Arthur David Pennington was born on May 18, 1923, in Memphis, Tennessee. His family lived in Hot Springs, Arkansas, but Art’s mother happened to be in Tennessee that week, visiting one of her sisters, when the time came to deliver baby Pennington. Art’s parents, Harry and Fannie (nee Walker), already had two children, a son, James, who had been born in 1920, and a daughter, also Fannie, born in 1921. Harry worked two jobs, both as an elevator operator at a local hotel and as a janitor for the schools, and Fannie made but a nickel a day as a laundress and housekeeper. Even with three children to feed, though, the Pennington family survived the Great Depression intact.

Art recalled that he “was pretty mean when (he) was younger.”2 He credited his maternal grandfather with his temperament. Elmo Walker was a white Irish immigrant who at the turn of the century had had the temerity to fall in love with, and marry, a black woman. Through baseball and football, young Art was able to channel his anger and his ferocity into athletic excellence. He earned all-state honors in football at Hot Springs’ Langston High School, and also played baseball on a town team, the Highland Giants, with his father and brother.

It was his baseball time that shaped his later life in sports. “My Dad was quite a ballplayer and he saw that I was havin’ trouble hittin’ ‘em from the left side, left-handed pitchers, so he told me to switch.”3 Art did so, and began to excel. The manager of the barnstorming Zulu Clowns, Happy Foreman, noticed the man-child during a local contest, and hired him to play on their regional barnstorming squad in 1938.

In 1939 that team became the West Indian Royals. It was in a game against the Royals that Chicago American Giants’ manager Candy Jim Taylor discovered Pennington. Pennington later recounted, “The American Giants was playin’ the Memphis Red Sox in Memphis. My aunt sent me five dollars to come from Hot Springs to Memphis, so I got a tryout with the American Giants and they hired me right then. I beat out one of the old veteran shortstops. They had a grudge on me then; they didn’t like it at all.”4 Taylor had to convince Art’s mother that he would see to the boy’s safety in Chicago if she would allow him to sign, and that he would continue to attend church regularly. The deal closed when Taylor offered the family $300 to sign Pennington: $150 right then, for the family, and $150 when Art arrived in Chicago.

In Chicago, Pennington jumped into big-city life with both feet. He was never one to mix with drugs or alcohol or gambling. As he later observed, “I saw too many people come to a bad end messing with that stuff.”5 However, women were a different matter. He had an innate fondness for the opposite sex, and Chicago was a wonderful place for a young, athletic man to live in 1940. It did not take long for him to wed Mattie, a Chicago girl, but that marriage did not survive. It was followed by brief nuptials with women named Mary Ann and Jewell (their last names are lost to the 2008 Iowa flood), but those ended as well.6

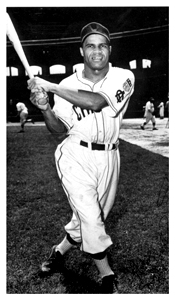

On the diamond, Art excelled against some of the finest players in the history of the Negro Leagues. In 1942, he was selected to play in both of that year’s East-West All-Star games. In the first contest, on August 16 at Comiskey Park, he pinch-hit for Tommy Simpson in the ninth inning, but struck out. Two days later, at Municipal Stadium in Cleveland, he again pinch hit, this time in the eighth inning for Fred Bankhead, and again failed to reach base.7

With World War II raging, the Army found Pennington. “I didn’t want to go into the army in the first place and when they drafted me, I was in Hot Springs, Arkansas. I told ‘em, I said, “I don’t want to go in the army. What I got to fight for? I can’t eat in no place, can’t go no place. Why do I wanna fight? I don’t know nothin’ bout no Japs. They ain’t did nothin’ to me.”8 It was a clear example of determined, peaceful civil disobedience, one strikingly similar to the one Muhammad Ali would demonstrate a generation later. Dr. J.B. Martin, owner of the Chicago American Giants, intervened. With Pennington working in a local rubber plant on a temporary deferment, Martin convinced the Hot Springs/Little Rock draft board to move Art’s case to Chicago. Martin then exerted additional pressure, and the board eventually released Pennington from military service.9

By 1944, a year in which he batted .299 in league play, Pennington was earning a reported $400 per month.10 Art demanded a $200/month raise, but Martin denied the request. The rancor between player and team soon reached a tipping point, and on June 22, the Chicago Defender reported “Bad Boy Pennington is Indefinitely Suspended.”11 There would be no pay raise, but Martin did give Pennington an extra $100 to clear an old debt. It was sufficient.

By mid-1945, Art was batting .359 and enjoying his best year as a professional. When agents recruiting players for teams in the Mexican League approached him, though, the offer of a $1,000 bonus was too tempting to resist. “We was in New Orleans playin’ a game and they come in, got three of us. They asked me what’s the best three we had on the American Giants that would go for a thousand apiece…I said, “What you need?” He said, “We definitely want you and we want a second baseman and we want a left-hand pitcher”. “So I got Lefty McKinnis, one of our ace pitchers, and Jesse Douglas…we all drove to Mexico and we played for the Monterrey team.”12

Pennington moved over to the Puebla squad for the 1947 season, batting .291 in 1947 and .301 in 1948. He also took yet another wife. Pennington, who lived his entire life with the philosophy that skin color did not define a person, met Ana (Anita) Aureoles, a red-headed white woman from Spain and living in Mexico City, who was seven years his senior. He was smitten. The two soon wed and later had two daughters, Anaperla and Angela, but the marriage did not survive the 1950s.

Art spent the winter of 1947/48 playing in the Cuban Players League for the Leones. That year, playing for new manager Chico Hernandez, and alongside white U.S. players like Red Hayworth and James “Red” Steiner and Cuban stars such as Sandy Consuegra, Pennington and the Leones won the only Cuban Players League title with a 50-41 record. Pennington batted only .234 for the winter, but his defensive versatility and speed made him an invaluable cog in the Leones machine.

By 1949, with baseball at least superficially integrated, Art’s mother coerced him into returning to the United States. Grudgingly abandoning both his $5,000 salary and a freedom from racism that he had never known up north, he and Anita returned to Chicago. The Negro Leagues had granted a one-time amnesty to all of the Mexican League defectors, as the returning players were viewed as critical to continuing league viability now that Jackie Robinson had broken the color barrier.13

Pennington’s trip back to the United States with his Mexican wife immediately reminded him of what he had left behind. “(My wife) couldn’t speak English. We came out of Mexico and we took a train to catch a bus out of Little Rock, Arkansas. They wouldn’t let her go to the colored waiting room stay with me; they wanted her to go to the white waiting room. I said, ‘No way, because she couldn’t speak any English.”14

Amnesty or not, after 57 games the Giants sold Pennington’s contract to the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League.

For a variety of reasons, notably the hostile reality of racism toward Art and his white wife, Pennington initially struggled at the plate in Portland. After 53 at-bats in the PCL, the Beavers sold his contract to their primary minor league affiliate, the Salem Senators of the Western League. In Salem Pennington regained his stroke, and ended 1949 by barnstorming with Buck Leonard and others on the New York Stars.

For a variety of reasons, notably the hostile reality of racism toward Art and his white wife, Pennington initially struggled at the plate in Portland. After 53 at-bats in the PCL, the Beavers sold his contract to their primary minor league affiliate, the Salem Senators of the Western League. In Salem Pennington regained his stroke, and ended 1949 by barnstorming with Buck Leonard and others on the New York Stars.

In 1950, Pennington finally returned to Chicago. That year he batted .370 in Negro American League play, and was again selected to the East-West game. This time, however, he started the August 20 game at Comiskey Park, and in front of 24, 614 spectators went 1-3 at the plate with a run scored and one driven in.15 Manager Buck O’Neil’s West team won that day, 5-3.

The following winter, after not playing professionally during the 1951 season, Pennington headed to Venezuela, where he earned close to $3,000 by batting .360 (over 203 at-bats) for the Patriotas-de-Venezuela. In 1952, Art made a move to the desegregating U.S. minor leagues. In Keokuk, Iowa, he led the 3-I League in batting (.349 in 1952), and spent time playing for Cibaeñas of the Dominican League. In 1953 and 1954, he played for the Cedar Rapids Indians, and began working an off-season job with the local railroad.

Could he have made it to the integrated major leagues? “I know I was cheated,” he said in 2007, “but I never think about that”.16 He always maintained that his interracial marriage to Anita was a bridge too far for the sports-consuming public in the 1950s, and in comparing his case with that of Luke Easter,17 he may have been right. He never felt, though, that he could have remained in control the way Jackie Robinson did in 1947. “I didn’t have the brains that Jackie did. I don’t know if I coulda took it.”18

Pennington played two seasons with the Bismarck Barons of the Manitoba-Dakota (MANDAK) League in 1955 and 1956. In 1957, in large part due to persistent lobbying by Pennington’s old Mexican League teammate Sal Maglie, the New York Yankees signed Art to a minor league contract. Pennington had played on a semi-pro team in the Southern Minnesota league that year, but signed with the Yankees for the 1958 season. Assigned to St. Petersburg, he made the Florida State League All-Star team at age 35, posting a “slash line” of .339/.443/492, and helped lead the Saints to the league crown. Their 101 wins put them 19 games ahead of second-place Daytona.

The organization promoted him to Modesto, of the Class C California League, for the 1959 season. Art batted only .256 that year, and although the Reds won their league as well, he finally retired from professional baseball.

Pennington’s lifetime baseball numbers were superb. At one time or another he played every position on the diamond except catcher. Overall, he batted .336 over his Negro American League career, .300 in the Mexican League, and .322 in the U.S. minor leagues, along with unknown success on the various barnstorming loops. In 1952, he led the newly integrated Three-I League (A) in hitting at the relatively wizened age of 29.

In the winter of 1955, Art worked for the local railroad in Cedar Rapids in the offseason, and was photographed carrying a large railroad tie over his shoulder. The picture ran in the Cedar Rapids Gazette with a caption: “The man swinging the big bat that looks suspiciously like a railroad tie is Art Pennington, former Cedar Rapids Three-I leaguer, who … has been working on the railroad in C.R. since the season ended”.19 Arthur Collins, the founder of Collins Radio (now Rockwell-Collins), saw the photo and in 1959 offered Art a job doing electrical assembly work in his main plant in Cedar Rapids. The only condition was that Pennington would consider playing for the company’s entry in the local industrial baseball league.

Pennington readily agreed, and he – along with Arnie Green and Horace Garner – became the three black players to play in the Manufacturers and Jobbers League. Garner had hard-won experience in integrating baseball leagues, having suffered thrown rocks, bottles, and invective as he teamed with Hank Aaron and Felix Mantilla to integrate the South Atlantic League back in 1953. In Cedar Rapids there was nothing but eager acceptance by the community. Even at the relatively wizened age of 38, Pennington still awed both fellow players and the crowds with his skills, and he fit right in to the organizational culture at Collins Radio.20

In Cedar Rapids, the again-divorced Pennington met Elizabeth, a co-worker at Collins’ Radio and the woman who would become his fifth and final wife. Together the two, along with a local business partner, opened the first mixed-race dance club in eastern Iowa. Local authorities shuttered the “Home Run Club” in 1963, ostensibly due to building electrical and plumbing non-compliance. Pennington always suspected it was more due to the collective, communal discomfort with the change he was fostering.21

In 1967, Pennington carried his message further by becoming the first non-white person ever to run for Linn County (Iowa) Sheriff. In 1969 he repeated the feat, this time campaigning for mayor of Cedar Rapids. In every case, his platform was the same. “I am seeking office to better the conditions in Cedar Rapids; to give the people better police protection; to give the working man and woman the same protection as the rich. I think I can do more for the urban renewal people who don’t want to lose their homes.”22 At that time, in a community where less than 2% of the population identified as black, his was not a racial stance. Pennington continued to see his skin color as a trait, not as his identity. He moved within the system to improve that awareness among his new community. The message was threatening to some, recalled Cary Hahn, a local Cedar Rapids news media figure, but it forced the community to mature and progress.23

Art and Betty eventually divorced, and he retired from Rockwell-Collins in 1985. For the next two decades, Pennington visited schools and talked with local youth about life and baseball in the Negro Leagues. The 2008 floods in eastern Iowa destroyed the basement of his home and eventually drove him to declare bankruptcy. In 2016 he entered an assisted living facility in Cedar Rapids. On January 4, 2017, “Superman” passed away in his sleep.

Art Pennington starred for the Chicago American Giants in the Negro American League, and he left his mark on the collective baseball lore of Mexico, Cuba, and even Venezuela. He played with and against some of the most celebrated legends of the Negro Leagues, including Josh Gibson, Willie Wells, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, Buck Leonard, and the great Satchel Paige. He excelled in the integrated minor leagues. Pennington finally settled down in Cedar Rapids because it offered employment and a degree of acceptance. The city offered him a relatively secure haven, and he returned the favor by trying to acquaint his new neighbors with the absurdity of even the most subtle racism. His legacy of accomplishment and memory, in baseball and in life, is such that there can be no doubt that Art Pennington was, perhaps, even more than “Superman.”

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Joe DeSantis and fact-checked by Jeff Findley.

Sources

“Art Pennington, last Negro League All-Star, passes away at 93”, online: http://www.baseballhappenings.net/2017/01/art-pennington-last-negro-league-all.html; retrieved March 12, 2017

Heaphy, Leslie. Black Baseball and Chicago (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2006)

Johnson, William:

- Interview with Cary Hahn, April 8, 2017

- Interview with Harold Primrose, former M&J player, and Bob Brooks, former M&J League president, in December 2013.

- Interview with Art Pennington and William Valencia, September 6, 2016.

- Telephone interview with Art Pennington on November 8, 2013

Kelley, Brent. Voices from the Negro Leagues: Conversations with 52 Baseball Standouts of the Period, 1924-1960 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 1997)

Lanctot, Neil. Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Fall of a Black Institution (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006).

Lester, Larry. Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: Bison Books, 2002).

Pennington, Art. Art Pennington virtual scrapbook (National Baseball Hall of Fame) Online: http://collection.baseballhall.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A294068#page/5/mode/1up

Salin, Anthony. Forgotten Heroes (Chicago: Master’s Press; 1999)

Simkus, Scott. Outsider Baseball: The Weird World of Hardball on the Fringe, 1876-1950 (Chicago Review Press, 2014)

“The Last At Bat” online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4mOyQLP48Yo”

Newspapers

Chicago Defender, June 22, 1944.

The Cedar Rapids Gazette, Sunday, October 14, 1955

The Cedar Rapids Gazette, October 19, 1969

Notes

1 Leslie Heaphy, Black Baseball and Chicago (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2006), pp 107-110. Also, some details are added courtesy of an interview with Art Pennington and his friend/manager Billy Valencia, on September 6, 2016. It is also recounted in “The Last At Bat,” a 2010 radio interview with Art Pennington available online at “ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4mOyQLP48Yo” and in Tony Salin’s 1999 book Forgotten Heroes (Chicago: Master’s Press).

2 “The Last At Bat: Negro Leagues Star Art “Superman” Pennington Interview 2/15/2010”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4mOyQLP48Yo

3Brent Kelley. Voices from the Negro Leagues: Conversations with 52 Baseball Standouts of the Period, 1924-1960 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 1997).pp 76-84

4 Ibid.

5 Telephone interview with Art Pennington on November 8, 2013

6 National Baseball Hall of Fame, Art Pennington virtual scrapbook. Online: http://collection.baseballhall.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A294068#page/5/mode/1up

7 Larry Lester. Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: Bison Books, 2002).

8“The Last At Bat”

9 Kelley, pg. 80. See also the biography at http://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Art_Pennington#The_final_years

10 Ibid., pg. 77

11Chicago Defender, June 22, 1944.

12 Kelley.

13 Neil Lanctot. Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Fall of a Black Institution (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006). Pg 347

14“Art Pennington, last Negro League All-Star, passes away at 93”, online: http://www.baseballhappenings.net/2017/01/art-pennington-last-negro-league-all.html; retrieved March 12, 2017

15 Lester, pg. 337

16 Radio interview (2007); online: voiceofseason.com/an-hour-with-superman

17 Scott Simkus. Outsider Baseball: The Weird World of Hardball on the Fringe, 1876-1950 (Chicago Review Press, 2014), pg. 11

18 Ibid.

19The Cedar Rapids Gazette, Sunday, October 14, 1955, pg. 5

20 Interview with Harold Primrose, former M&J player, and Bob Brooks, former M&J League president, in December 2013.

21 Interview with Art Pennington and Billy Valencia, September 2016.

22The Cedar Rapids Gazette, October 19, 1969, pg 12A

23 Interview with Cary Hahn, April 8, 2017

Full Name

Arthur David Pennington

Born

May 18, 1923 at Memphis, TN (US)

Died

January 5, 2017 at Cedar Rapids, IA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.