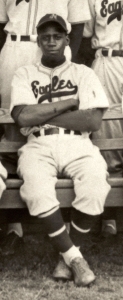

Leon Ruffin

A superior defensive catcher, the well-traveled Leon Ruffin was a member of the 1946 Newark Eagles and a Negro League all-star that same year. Ruffin’s defensive skills were legendary. He was noted for his ability to handle pitching staffs and to detect a batter’s weakness. He had a strong throwing arm that was considered one of the best in the game. Cool Papa Bell called him “one of the best catchers I ever saw,” high praise from a man who played against Hall of Fame backstops Josh Gibson, Biz Mackey, and Roy Campanella.1

A superior defensive catcher, the well-traveled Leon Ruffin was a member of the 1946 Newark Eagles and a Negro League all-star that same year. Ruffin’s defensive skills were legendary. He was noted for his ability to handle pitching staffs and to detect a batter’s weakness. He had a strong throwing arm that was considered one of the best in the game. Cool Papa Bell called him “one of the best catchers I ever saw,” high praise from a man who played against Hall of Fame backstops Josh Gibson, Biz Mackey, and Roy Campanella.1

At the plate, the right-handed-hitting Ruffin was a light hitter with little power. He often finished the season under what is now known as the Mendoza line.2 Despite his low batting average and lack of power, Ruffin was known for his patience at the plate and for his ability to handle the bat and play small ball. He often worked pitchers deep into the count and helped to move runners around the bases with a bunt or by hitting behind the runner. Sam Allen, who grew up in Norfolk and saw Ruffin play on the semipro circuit in and around Portsmouth after his Negro League career, said, “He was a heck of a bunter. He had the ability to place that ball wherever he wanted.”3

Charles Leon Ruffin was born on February 11, 1912, in Portsmouth, Virginia. He was the third child and oldest son born to Thomas and Hattie (Holmes) Ruffin. Thomas was a laborer who worked on the dry docks of the Portsmouth-based Norfolk Naval Shipyard. Hattie was a laundress.4 The couple and their six children were renting a home on 931 Seventh Street in Portsmouth at the time of Thomas’s death on July 17, 1921, when Leon was 9 years old. Leon completed the ninth grade before going to work full-time.

Portsmouth, located on the western side of the Elizabeth River directly across from Norfolk, was booming in the early twentieth century. The population of Portsmouth more than tripled during the first 20 years of the century, largely due to the shipyard. Portsmouth became a popular destination among barnstorming Negro League teams. Many of the greats of the game — players like Gibson, Satchel Paige, and Mule Suttles — made appearances at Sewanee Stadium.5 The city soon became a hotbed of Negro League talent. Ruffin and Buster Haywood were two of the best players to come out of Portsmouth.6

By 1930, Ruffin was living with his mother, five siblings, and three nieces in a small rented house at 687 Nelson Street in Portsmouth. By this time, he had also followed in his father’s footsteps and was working as a laborer at the Naval Shipyard.7 When he wasn’t working, Ruffin, who grew up playing baseball and football on the sandlots around Portsmouth, was making a name for himself as an athlete. According to Clay Shampoe and Thomas Garett, authors of Baseball in Portsmouth, Virginia, “Ruffin was an excellent athlete on diamonds and the gridiron for several Portsmouth and Norfolk semipro teams.”8 Sam Allen suggested that Ruffin’s exploits on the football field were legendary among local residents. “He was a very good football player and would have had a good career in football had he had the opportunity to go to school,” Allen said.9

Ruffin was built like a barrel. By this time the stocky catcher’s 5-foot-11 frame had filled out to 175 pounds and his success at the semipro level in the early 1930s began to draw the attention of Negro League scouts. In 1935 Ruffin joined the Brooklyn Eagles of the Negro National League and stayed with the team after owner Abe Manley and his new wife, Effa, moved the team to Newark, New Jersey, for the 1936 season.

Ruffin’s first two seasons with the Eagles foreshadowed most of his career. While Negro League statistics are incomplete and in some cases nonexistent, those that are available suggest that Ruffin struggled at the plate. According to The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Leagues, during his first two seasons with the Eagles he hit a combined .171.10 But despite his lack of productivity at the plate and his relative inexperience, Ruffin proved to be an above-average defensive catcher.

Ruffin married Daisy Brooks of Occupacia, Virginia, sometime in the mid-1930s. The couple moved into a small, rented home at 651 Fayette Street in Portsmouth and lived there with Daisy’s younger brother, Richard. They eventually had one child, Leon Jr.

Ruffin was traded to the Pittsburgh Crawfords before the 1937 season. He served as the team’s backup catcher to all-star Pepper Bassett in 1937 and became the starter in 1938. When Gus Greenlee, owner of the Crawfords, decided to move the team to Toledo, Ohio, in 1939, Ruffin sought any opportunity to avoid the transition. He wrote to Abe Manley, requesting that the Eagles reacquire him, offering to play for $140 a month.11 Manley accommodated his request and in May of 1939 traded pitcher Bob Evans to the Crawfords for Ruffin.12

Ruffin’s second stint with the Eagles was short-lived. By midseason he was traded to the Philadelphia Stars, who were in need of another catcher after Bill Perkins jumped the Stars to play in the Mexican League.13

Official Negro League seasons were short, at 40 to 60-plus games, only about a third or more the length of a 154-game major-league schedule.14 However, that doesn’t mean there weren’t plenty of opportunities for Ruffin and other Negro League players to play. Barnstorming and engagements with semipro teams allowed Ruffin the opportunity to supplement his $740-a-year income as a presser at the dry cleaners in Portsmouth. And, of course, there were opportunities south of the border.

Ruffin returned to the Newark Eagles in 1942, his third time with the club. He batted .248 and was the batterymate of Day when the right-hander one-hit the Baltimore Elite Giants and struck out a Negro League-record 18 hitters, including the 20-year-old Campanella three times. Ruffin remained with the Eagles until, true to his Portsmouth roots, he enlisted in the US Navy during World War II. Ruffin served in the Navy from 1943 to 1945.15

With the exception of a few games in 1944, Ruffin missed nearly two full seasons to the war. After being discharged from the Navy, he returned to the Eagles for the fourth time in his career. However, this season would be like no other for Ruffin and the Eagles.

Despite his light hitting, Ruffin was the team’s regular catcher in 1946. His work behind the plate more than compensated for any deficiencies with the bat. The Eagles were riding an eight-game winning streak in June when the Newark Evening News credited the team’s success in part to the work of its seasoned catcher: “The great showing of the pitching reflects upon the skill that has been exhibited by Leon Ruffin behind the plate. Ruffin is a veteran receiver and his faultless handling of the hurlers has won much praise from veteran baseball fans and players.”16

Ruffin enjoyed one of his better offensive seasons in 1946 and occasionally helped out with his bat. On June 30 he broke up a scoreless tie with a solo home run into the left-field bleachers at Ruppert Stadium in support of Day’s five-hit, 3-0 victory over the Philadelphia Stars. Two months later, on August 27, he contributed four hits to the Eagles’ 23-hit, 15-1 victory over the New York Black Yankees. Ruffin reportedly finished the 1946 season batting .250 (Seamheads shows him at .248).17

His efforts behind the plate and improved hitting earned Ruffin a spot on the Negro League’s East All-Star squad along with teammates Larry Doby, Monte Irvin, Lennie Pearson, and Day. That year, the East (Negro National League) and West (Negro American League) played two all-star games, one in Washington and the East-West Classic in Chicago.

On August 15 there were 16,268 fans in attendance to watch the East All-Stars play the West All-Stars at Griffith Stadium. Under the rules of the games, no pitcher was allowed to throw more than three innings, which required the managers to utilize their benches.18 Ruffin entered the game as a defensive replacement in the top of the fifth inning. He replaced Gibson behind the plate after the legendary catcher was lifted for a pinch-runner, the Philadelphia Stars’ Murray Watkins, in the bottom of the fourth inning. Ruffin went 0-for-1 before being replaced by Louis Loudon of the New York Cubans in the East’s 6-3 victory over the West.19 The game was notable because it was the first East-West Game held in the nation’s capital and the first with no extra-base hits.

On August 18 the 14th annual East-West Classic in Comiskey Park drew a crowd of 45,474, the second largest turnout in the event’s history.20 The West beat the East, 4-1, its fourth straight win and eighth victory overall in the series. Josh Gibson worked the entire game behind the plate for the East and Ruffin did not play.

The 1946 Negro League World Series was one for the ages. The high-flying Eagles, winners of the Negro National League pennant, were matched against the Negro American League champion Kansas City Monarchs. The Series was a back-and-forth affair as the Eagles rallied from a three-games-to-two deficit to capture the Series in seven games. Ruffin caught all seven games and went 7-for-25 (a respectable .280) with 4 RBIs against a strong Kansas City Monarchs pitching staff that included Paige and Hilton Smith.21

Ruffin and Day jumped to Mexico in 1947. He hit only .229 for the Mexico City Reds before returning to the United States and resuming his career in the Negro Leagues.

With the integration of baseball, the Negro Leagues experienced a dramatic decline in popularity. As a result, the Negro National League disbanded after the 1948 season and the Eagles joined the Negro American League. Effa Manley decided to combat the loss of revenue caused by integration by selling the team to W.H. Young, who relocated the Eagles to Houston in 1949.22

Ruffin returned to the Eagles in 1949 and played his final two professional seasons in Houston. At the time, the 37-year-old backstop was the longest-tenured Negro League catcher. He hit .174 in 1949 and .194 in 1950.23 Low attendance was a common theme for all of the NAL teams, but the Eagles were also hurt by the fact that they finished in last place during both of their years in Houston.24 Hoping to find a more supportive fan base, the Eagles moved to New Orleans.

With his professional career now behind him, Ruffin returned to Portsmouth for good. He was a fixture on local semipro teams, serving as manager and occasionally catching a few innings. Sam Allen, who grew up in Norfolk and played in the Negro Leagues during their waning years, played against teams managed by Ruffin.25 “He was very knowledgeable,” Allen recalled. “Like most catchers, he understood the whole game. He was an excellent manager for young ballplayers.”26

When he wasn’t managing and playing baseball on the semipro circuit, Ruffin worked as a presser at a local dry-cleaning store. On August 14, 1970, Ruffin suffered a stroke and died. He was 58 years old. Despite some family members’ wishes that he not be buried in Portsmouth’s Lincoln Cemetery, a poorly maintained graveyard that served the African-American community, Ruffin’s widow, Daisy, insisted that he be interred there. She was buried there herself in March of 2010.

On September 29, 2010, a small ceremony attended by about 20 people, including Ruffin’s son, Leon Ruffin Jr., was held to dedicate a marker that had been installed at the foot of Ruffin’s grave earlier that year. The marker was part of a national movement, led by the Society for American Baseball Research’s Negro Leagues Committee, to recognized long-forgotten Negro League players.

The Georgia gray granite marker is adorned with a pair of crossed bats, with a ball beneath, and a catcher’s mitt.27 The marker reads:

Charles Leon Ruffin

Negro League Legend

1935-1950

Catcher

1946 World Champion Newark Eagles

1946 East-West Negro League All-Star

Understanding where Leon Ruffin and many of his contemporaries fit into the landscape of Negro League baseball history is often difficult. As Lawrence Hogan, author of Shades of Glory, wrote, “There exists no official source of statistics … no compilations of scorecards. … Many gaps exist in the historical record.”28 Most of what we have to go on is anecdotal in nature. However, one thing is certain: In 1946 Leon Ruffin was the catcher for the greatest Negro League team in the world.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also relied on Baseball-reference.com and Seamheads.com.

Sam Allen interviews with author, December 3 and 17, 2018. Recorded conversations in author’s possession.

Notes

1 Cool Papa Bell Oral History Interview, September 27, 1981. Retrieved from collection.baseballhall.org/PASTIME/cool-papa-bell-oral-history-interview-1981-september-27-3.

2 The Mendoza line is a baseball term for batting around or below .200 — mediocrity. The term was coined by George Brett after Mario Mendoza. The term has also crossed over into America’s pop-culture lexicon and is frequently used to describe almost any type of subpar performance, from the performance of stocks and mutual funds to bad grades, and to quotas for salespeople.

3 Sam Allen, personal interview, December 3, 2018.

4 “United States Census, 1920,” database with images, FamilySearch (familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MJF8-36V : accessed March 7, 2018), Leon Ruffin in household of Thomas Ruffin, Portsmouth Lee Ward, Portsmouth (Independent City), Virginia, United States; citing ED 235, sheet 4B, line 67, family 90, NARA microfilm publication T625 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1992), roll 1905; FHL microfilm 1,821,905.

5 Bill Leffler, “Hampton Roads Plays Host to Major Salute to Negro Leagues,” The Virginian-Pilot, June 13, 2007. Retrieved from pilotonline.com/news/local/article_b0a08643-62ec-5659-b131-83a12fcd9a1e.html. Sewanee Stadium was the old baseball park near Washington and Lincoln streets in Portsmouth that frequently hosted local semipro and barnstorming games.

6 Buster Haywood was a catcher with the Indianapolis and Cincinnati Clowns, Birmingham Black Barons, and New York Cubans. Like Ruffin, Haywood became a semipro manager and is credited with helping discover Hank Aaron in 1951.

7 “United States Census, 1930,” database with images, FamilySearch (familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:CCDJ-YZM: accessed March 7, 2018), Leon Ruffin in household of Hattie Ruffin, Portsmouth, Portsmouth (Independent City), Virginia, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 16, sheet 3A, line 3, family 51, NARA microfilm publication T626 (Washington: National Archives and Records Administration, 2002), roll 2473; FHL microfilm 2,342,207.

8 Clay Shampoe and Thomas Garett, Baseball in Portsmouth, Virginia (San Francisco: Arcadia Publishing, 2004).

9 Sam Allen, personal interview, December 17, 2018.

10 James Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Leagues (Boston: DaCapo Press, 2002).

More recent Seamheads.com stats show him averaging .189 over the two seasons.

11] Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Sam Allen said that Ruffin had played this second year in Mexico. Sam Allen, December 17, 2018. See also baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Leon_Ruffin.

14 Thomas Kern, “Leon Day,” SABR BioProject.

15 Alfred M. Martin & Alfred T. Martin. The Negro Leagues in New Jersey: A History (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2008), 66.

16 “Eagles Riding Win Streak: Carry Eight-Game String Into Tilt Here with Grays Tonight.” Newark Evening News, June 25, 1946: 26.

17 James Riley.

18 “Negro Nationals Beat Americans in All-Star Game,” Boston Globe, August 16, 1946: 6.

19 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 274.

20 James Segreti, “West Defeats East All-Star Negro Nine, 4-1: Gains 8th Victory Before 45,474,” Chicago Tribune, August 19, 1946: 27.

21 Richard J. Puerzer, “The 1946 Negro League World Series: The Newark Eagles vs. the Kansas City Monarchs,” in Rick Bush and Bill Nowlin, eds., The Newark Eagles Take Flight: The Story of the 1946 Negro League Champions (Phoenix: SABR, 2019).

22 Robert Fink, “Houston Eagles,” Handbook of Texas, Retrieved from tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/xoh06.

23 James A. Riley.

24 Robert Fink.

25 Sam Allen played for the Kansas City Monarchs in 1957, the Raleigh Tigers in 1958, and the Memphis Red Sox in 1959.

26 Sam Allen, personal interview, December 17, 2018.

27 Ed Miller, “Baseball Fans Keep Negro League Player’s Legend Alive,” Virginian-Pilot [Norfolk], September 26, 2010. Retrieved from https://pilotonline.com/guides/african-american-today/article_8444af87-4abf-5cd3-9317-9b8b1f0bbd1b.html

28 Lawrence Hogan, Shades of Glory: The Negro Leagues and the Story of African-American Baseball (New York: National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, 2006), 380, quoted in Bill Johnson, “Josh Gibson,” SABR BioProject.

Full Name

Charles Leon Ruffin

Born

February 11, 1912 at Portsmouth, VA (US)

Died

August 14, 1970 at Portsmouth, VA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.