1919 White Sox: Epilogue (Offseason, 1919-20)

This article was written by Jacob Pomrenke

This article was published in 1919 Chicago White Sox essays

One day after the 1919 World Series ended, Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey responded publicly to rumors that his team had intentionally thrown games to the Cincinnati Reds. “I believe my boys fought the battles of the recent world’s series on the level,” he told the Chicago Times, and he even offered a $10,000 reward if anyone could provide him with credible evidence of a fix.

One day after the 1919 World Series ended, Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey responded publicly to rumors that his team had intentionally thrown games to the Cincinnati Reds. “I believe my boys fought the battles of the recent world’s series on the level,” he told the Chicago Times, and he even offered a $10,000 reward if anyone could provide him with credible evidence of a fix.

It was an empty promise, because Comiskey already had all the evidence he needed. According to reporter Hugh Fullerton, a friend and ally of the White Sox owner, Comiskey knew all about the fix before Game One — and he wasn’t alone, for the World Series fix was the worst-kept secret in baseball.

Comiskey, American League President Ban Johnson, and other baseball officials spent the offseason of 1919-20 investigating the ugly rumors that had plagued the fall classic, but ultimately they chose to ignore the many red flags they discovered. The revelation of the World Series fix to the public at large came about only after nearly another full season had been played, and even then it may have never come to light if not for a long-standing feud between Comiskey and Johnson, who pushed Chicago civic leaders to empanel a grand jury and look into the World Series rumors. In addition to airing baseball’s dirty laundry with the Black Sox Scandal, their feud led to the installation of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis as commissioner and changed the power structure of baseball forever.

The World Series fix came as no surprise to anyone knowledgeable about baseball or its intimate relationship with gambling. Historians Harold and Dorothy Seymour later wrote, “When the scandal of 1919 became public knowledge, the men who controlled Organized Baseball acted as though it were a freakish exception, a sort of unholy mutation. … The evidence is abundantly clear that the groundwork for the crooked 1919 World Series, like most striking events in history, was long prepared.”

It took some time, however, for the dust to settle after the World Series ended. On October 10, the same day that Comiskey first defended his players publicly, Fullerton’s syndicated newspaper column asserted that seven unnamed members of the White Sox would not be back with the club in 1920. Years later, Fullerton claimed that he got their names — which turned out to be the seven accused Black Sox, minus Buck Weaver, who by most accounts had played his best and had not received a dime from gamblers — from Comiskey himself. In a vivid (possibly apocryphal) description of their meeting written in 1935, Fullerton tells of “a broken and bitter” Comiskey banging a table with his fist and crying, “Keep after them, Hughie; they were crooked. Some day you and I will prove it.”

Unbeknownst to Fullerton, Comiskey was already hard at work behind the scenes gathering more information about the fix. Three days after the World Series ended, on October 12, Comiskey sent White Sox manager Kid Gleason to St. Louis to meet with theater owner Harry Redmon, who claimed to have lost more than $5,000 betting on the World Series. Redmon, apparently seeking some of Comiskey’s reward money to recoup his gambling losses, confirmed to Gleason the names of the eight ballplayers involved in the fix, including Weaver, who had attended multiple pre-Series meetings with the rest of the players.

Redmon had firsthand knowledge: After the White Sox had surprisingly won Game Three and it appeared as if the fix had been called off, Redmon was connected with a group of Midwestern gamblers who launched an attempt to raise more money to pay off the players and revive the fix. Redmon and fellow St. Louis gambler Joe Pesch repeated the fix details to Comiskey in a second meeting in late December at the White Sox offices. Comiskey again ignored his pleas for the reward.

Near the end of October, White Sox team counsel Alfred Austrian met with the head of a private investigation firm, John R. Hunter of Hunter’s Secret Service, and hired him to find out as much as possible about the suspected players: Eddie Cicotte, Happy Felsch, Chick Gandil, Joe Jackson, Fred McMullin, Swede Risberg, Buck Weaver, and Lefty Williams.

For the next three months, Hunter and his detectives trailed the White Sox players around the country, interviewing their families and checking their bank accounts. Hunter’s first stop was California, where he met with McMullin, Gandil, Risberg, and Weaver, posing at one point as a real-estate salesman or as a reporter in an attempt to talk about the World Series with them. Hunter found nothing especially incriminating, but he filed regular reports back to Austrian and Comiskey throughout the offseason.

Another Hunter operative traveled to Milwaukee in November to check up on Happy Felsch, who was busy selling Christmas trees when he wasn’t fishing and hunting. The detectives also befriended two female acquaintances of Swede Risberg’s in Chicago to whom he had allegedly given money, but came back with no fruitful information. They were instructed, however, not to visit Eddie Cicotte at home in Detroit or Joe Jackson in Savannah, Georgia — the two players who would later crack open the case by testifying before a grand jury to their involvement.

The detectives’ reports themselves were filed away by Comiskey and not publicly revealed until 2007, when the Chicago History Museum acquired them as part of a large collection of Black Sox-related legal documents. Historian Gene Carney, in his seminal book Burying the Black Sox, argued that “the investigating Comiskey did — through his employees, his reporter friends like Fullerton, and his paid detectives — was carried on to ensure that any hard evidence found would remain hidden from public view.”

But too many people knew about the fix for it to remain hidden for long. In mid-November, reporter Frank O. Klein of a Canadian-based gambling publication called Collyer’s Eye became the first to publicly name the suspected White Sox fixers. (Although here too, Buck Weaver was omitted from the list of the accused.) American League President Ban Johnson, whose feud with Comiskey caused him to dismiss any opportunities to learn more about the fix during the World Series and perhaps even put a stop to it then, also began his own private investigation. His efforts uncovered additional evidence of the plot and, more important, key witnesses — namely, the gamblers Sleepy Bill Burns and Billy Maharg — who would later be used against the White Sox players in their criminal trial.

Another group that knew about, or at least strongly suspected, the World Series fix started talking during the offseason, too: teammates of the fixers who later became known as the “clean Sox.” Future Hall of Fame catcher Ray Schalk got into hot water when he bluntly told Collyer’s Eye on December 13, 1919, that seven White Sox players would not return to the team in 1920. Unlike Hugh Fullerton months earlier, Schalk even named them. (As usual, Buck Weaver was not among them.)

Although Fullerton continued to write about the rumors, railing against the baseball establishment for not taking the fix seriously, no other whistle-blowers besides Collyer’s Eye took up the cause that offseason. Fullerton’s accusations were routinely dismissed and even mocked in The Sporting News, Baseball Magazine, and other publications considered friendly to Organized Baseball. “There is not a breath of suspicion attached to any player, nor a hint that any effort in any manner was made to influence a player’s performance,” editor J.G. Taylor Spink wrote in the October 9, 1919, issue of The Sporting News.

As the calendar flipped over to the new year, talk of the World Series died down and Charles Comiskey likely breathed a sigh of relief. His championship team would remain mostly intact for the 1920 season. He began sending out new contracts to his players — even some of the suspected fixers — and the terms tended to be more generous than usual. Pitcher Eddie Cicotte agreed to a doubling of his base salary, from $5,000 to $10,000 (the same amount he later admitted receiving from gamblers to fix the World Series). Joe Jackson, who had been making $6,000 since 1914, signed a three-year deal for $8,000 per season. On average, according to Black Sox researcher Bob Hoie, White Sox players “received raises of about 32 percent, with no significant difference between the suspected and the clean Sox.” Although the White Sox already had one of the top payrolls in baseball, everyone in baseball was making more money.

Part of the reason for Comiskey’s extra generosity was that baseball had enjoyed a tremendous resurgence in popularity after World War I, leading to record profits for owners. This would continue in the 1920s as baseball entered a new era defined by high-scoring offenses and home-run records by the likes of Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Rogers Hornsby.

Attendance had soared across the major leagues in 1919, with three teams (the Reds, Tigers, and Yankees) setting single-season records at their home ballparks. In 1920 seven more teams would set attendance records, including the White Sox who, despite the lingering rumors of corruption, drew more than 833,000 fans to Comiskey Park. The Yankees, thanks in large part to Ruth’s record-setting 54 homers, became the first major-league team to surpass 1 million fans in a single season.

The offensive explosion that contributed greatly to baseball’s expanded popularity was triggered by several new rules instituted in February 1920, including an attempt at banning intentional walks and the prohibition of the spitball and other “freak deliveries” like the emery ball and Eddie Cicotte’s signature “shine ball.” Only a handful of spitballers were allowed to continue throwing the wet one in the major leagues; teams were forced to designate two players from their active rosters who could use the pitch. The White Sox selected Cicotte and future Hall of Famer Red Faber, who continued to throw the spitter until he retired in 1933; the last legal spitball was thrown a year later, in 1934, by Burleigh Grimes, who had also been grandfathered in.

Many modern fans have been led to believe that these changes were put in place as a result of the Black Sox Scandal, as a concerted effort to excite fans and clean up the game from the corruption and pitching-dominant style of play that characterized the Deadball Era (commonly defined as 1901 through 1919). But the spitball ban was enacted seven months before Cicotte, Jackson, and Lefty Williams testified to a Chicago grand jury, confirming their involvement with the World Series fix. And by Opening Day 1920, Babe Ruth was already one of baseball’s biggest stars, having broken the single-season home-run record with 29 homers for the Boston Red Sox the year before. His sale to the Yankees for the unprecedented price of $125,000 was the biggest story of that offseason, not the Black Sox Scandal.

One big change also being discussed in 1919-20 was an overhaul of baseball’s governing body, the three-man National Commission, and this would have more far-reaching consequences. The Commission — consisting then of AL President Ban Johnson, NL President John Heydler, and chairman August “Garry” Herrmann, owner of the Cincinnati Reds — was considered by just about everyone in baseball to be ineffective, with Johnson’s authoritarian ways alienating owners and players alike. Herrmann’s term was also up and the NL owners refused to reappoint him. In February 1920 he resigned from the National Commission and his absence threw Organized Baseball into even more turmoil.

Baseball’s inability to deal with its gambling problems was in no small measure due to the weakness of the National Commission, which had ignored most signs of game-fixing, betting on games by players or fans, and bribe offers. These transgressions generated a lot of smoke during the Deadball Era, and sometimes even fire. The poster child for this behavior was Hal Chase, a supremely talented but morally challenged first baseman who bounced from team to team fixing games for more than a decade. Even when he was caught red-handed by his manager, Christy Mathewson — the former New York Giants superstar whose credibility was as high as that of anyone else in the game — nothing had been done to stop Chase. Mathewson’s suspension of his player in 1918 was overturned by the National Commission and Chase was allowed to move on to the New York Giants, Matty’s old team. Chase promptly organized a new game-fixing ring with the Giants. When Mathewson learned about the World Series fix later, he reportedly told Hugh Fullerton, “Damn them, they [baseball officials] deserve it. I caught two crooks [Chase and Lee Magee] and they whitewashed them.” It was an out-of-character outburst for Matty, but his sentiments reflected baseball’s widespread frustration with the National Commission.

By the time the Black Sox affair finally came to light in the fall of 1920, the (now two-man) National Commission was in its final days. In the midst of the biggest scandal in baseball history, three American League owners who had been fighting with Ban Johnson for years were now in full-scale revolt against their league president. This group of “Insurrectos,” as they came to be called, included the White Sox’ Charles Comiskey, the Red Sox’ Harry Frazee, and Yankees co-owner Jacob Ruppert. The other five AL owners remained loyal to Johnson. This rift threatened to tear baseball apart and there was even talk of forming a new 12-team league with the eight NL teams, the three AL “Insurrectos,” and whichever owner who was loyal to Johnson broke ranks first.

In November 1920 the baseball owners decided to break up the National Commission once and for all by hiring a new single authority figure, federal judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who would rule the game with an iron fist for the next 24 years. Landis single-handedly solved the game’s gambling problem, too, with his decision in August 1921 to ban the eight White Sox World Series fixers for life. Not only did he punish acknowledged game-fixers and bribe-takers like Eddie Cicotte and Joe Jackson, but he also banished those with lesser degrees of guilt like Buck Weaver, who had only been accused of sitting in on meetings with gamblers. While the fairness of Landis’s decision has been debated for nearly a century afterward, there can be no doubting its effectiveness. As Landis biographer David Pietrusza has written, banning the Eight Men Out “had a great chilling effect on dishonest play — and talk of dishonest play. … Once prospectively crooked players knew that honest players would no longer shield them, the scandals stopped.” The commissioner’s decision cleaned up the game for good, which the National Commission had never been able to do.

The scandal also put an end to Charles Comiskey’s hopes for another championship. The White Sox were just a half-game behind the first-place Cleveland Indians on September 28, 1920 — the day the Black Sox players were suspended after Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams testified before the grand jury. With a depleted lineup for the season-ending series against the St. Louis Browns, the White Sox finished two games back with a 96-58 record.

From 1916 to 1920, Chicago had won two AL pennants and barely missed two more in five seasons. And with just three of the White Sox’ starting position players over the age of 30 in 1920 — not to mention four 20-game winners on the pitching staff in Cicotte, Williams, Red Faber, and Dickey Kerr, a first in baseball history — they were poised to contend for many years to come. Chicago might have provided strong competition for the New York Yankees’ emerging dynasty in the early 1920s. Even after the scandal broke up his team, Comiskey continued paying top dollar for new talent, bringing in the likes of infielders Luke Appling and Willie Kamm, outfielders Johnny Mostil and Bibb Falk, and pitcher Ted Lyons. Appling and Lyons were later inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, but they played almost their entire careers with the White Sox on second-division teams.

The scandal ended any chance of the White Sox establishing their own dynasty, and four decades passed before fans saw another World Series game on the South Side. That took place in 1959 — one year after the Comiskey family heirs sold the team to an ownership group led by Bill Veeck. The team set another attendance record that year, drawing 1.4 million fans to Comiskey Park, once known as the “Baseball Palace of the World.” The venerable ballpark was replaced in 1991 by a $167 million facility also named Comiskey Park at 35th Street and Shields Avenue. In 2005 that stadium, since renamed U.S. Cellular Field, finally celebrated the franchise’s first World Series championship since the Black Sox Scandal.

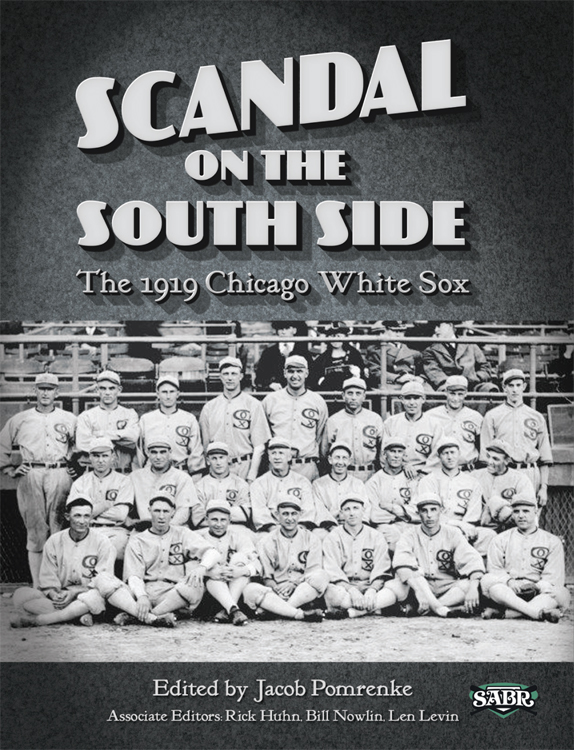

JACOB POMRENKE is SABR’s Director of Editorial Content, chair of the Black Sox Scandal Research Committee, and editor of “Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox” (2015).

Sources

Carney, Gene. Burying the Black Sox: How Baseball’s Cover-Up of the 1919 World Series Fix Almost Succeeded. (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2006).

Carney, Gene. “Comiskey’s Detectives,” Baseball Research Journal, Volume 38, Issue 2 (Cleveland, Ohio: Society for American Baseball Research, Fall 2009).

Felber, Bill. Under Pallor, Under Shadow: The 1920 American League Pennant Race That Rattled and Rebuilt Baseball (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2011).

Fullerton, Hugh. “Fullerton Says Series Should Be Called Off,” Atlanta Constitution, October 10, 1919.

Fullerton, Hugh. “I Recall.” The Sporting News, October 17, 1935.

Klein, Frank O. “Catcher Ray Schalk in Huge White Sox Exposé.” Collyer’s Eye, December 13, 1919.

Klein, Frank O. “Discover ‘Pay Off’ Joint in White Sox Scandal?” Collyer’s Eye, November 15, 1919.

Pietrusza, David. Judge and Jury: The Life and Times of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 1998).

Seymour, Harold, and Dorothy Z. Seymour. Baseball: The Golden Age (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971).

Spink, J.G. Taylor. “Concerning Bets and Bettors.” The Sporting News, October 9, 1919.

“When Baseball Gets Before The Grand Jury.” The Sporting News, October 7, 1920.