1919 White Sox: Prologue (Offseason, 1918-19)

This article was written by Jacob Pomrenke

This article was published in 1919 Chicago White Sox essays

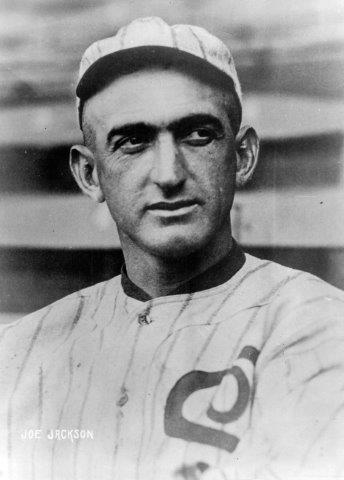

It’s accepted wisdom today that the Chicago White Sox, in the final years of the Deadball Era, were on their way to becoming one of the greatest teams in baseball history. Led by Shoeless Joe Jackson, Eddie Collins, and Ray Schalk in the field and Eddie Cicotte, Lefty Williams, and Red Faber on the mound, the White Sox captured a World Series championship in 1917 and were in serious contention to win two more titles in 1919 and 1920. If not for the corruption of the eight Black Sox players who were later banned from Organized Baseball for fixing the 1919 World Series, there’s no telling how good they might have been for years to come.

It’s accepted wisdom today that the Chicago White Sox, in the final years of the Deadball Era, were on their way to becoming one of the greatest teams in baseball history. Led by Shoeless Joe Jackson, Eddie Collins, and Ray Schalk in the field and Eddie Cicotte, Lefty Williams, and Red Faber on the mound, the White Sox captured a World Series championship in 1917 and were in serious contention to win two more titles in 1919 and 1920. If not for the corruption of the eight Black Sox players who were later banned from Organized Baseball for fixing the 1919 World Series, there’s no telling how good they might have been for years to come.

But few observers shared that opinion about the White Sox entering the 1919 season. Coming off a disastrous sixth-place finish in a year shortened by World War I, and with a surprising managerial change in the offseason, South Side fans weren’t sure what to expect when their team took the field on Opening Day. You could say the same about baseball itself: Now that the Great War was finally over, no one quite knew what to expect.

Baseball in 1919 was at a crossroads — between the pitching-dominated Deadball Era that was about to end and the glamorous, home-run-happy era that was to epitomize the Roaring Twenties. Babe Ruth was already a star with the Boston Red Sox, but he was known as the best left-handed pitcher in the American League and not for his hitting exploits yet to come. Earlier in the decade, the major leagues had survived the threat of the upstart Federal League, which had folded due to financial troubles after challenging the American League and National League for supremacy. Nearly every major-league team was playing its games in new concrete-and-steel stadiums built within the last decade. Few ballparks were more celebrated than Charles Comiskey’s “baseball palace of the world” at the corner of 35th Street and Shields Avenue in Chicago. The White Sox would call Comiskey Park home for 80 years.

Baseball then was still a rough-and-tumble game, played by “shysters, con men, drunks, and outright thieves … [and] midwestern farm boys who came out of cow pasture Sunday leagues,” as author Bill James put it in his Historical Baseball Abstract. Gambling was rampant within baseball, and the two pastimes enjoyed an intimate, mutually beneficial relationship. Thousands of fans participated in popular daily or weekly “baseball pools,” similar to modern fantasy football leagues and basketball tournament brackets. Ballplayers also mixed freely with underworld figures at saloons, casinos, and pool halls in every city, offering insider tips and sometimes even placing bets on their own games. At some ballparks, notably Fenway Park and Braves Field in Boston, bettors congregated in certain sections of the grandstands to conveniently make wagers on the game taking place on the field. Baseball’s powers-that-be looked the other way because profits were strong and attendance was high.

But America’s involvement in World War I had disrupted the entire sport in 1918. Attendance at Comiskey Park dropped by more than 70 percent from the White Sox’ championship season of a year before. In July, the US government issued a mandatory “work or fight” order that affected most major-league players, who were forced to decide between enlisting in the military or taking a job deemed essential to the war effort. With their teams’ rosters depleted, baseball owners abruptly ended the season in early September and a lackluster World Series was played between the Boston Red Sox and Chicago Cubs. Like many fall classics played during the Deadball Era, the 1918 World Series was troubled by rumors of game-fixing, although any evidence to prove that the Series had been tampered with was thin. The White Sox ended the disappointing season on an eight-game losing streak, finishing with a 57-67 record, 17 games behind the champion Red Sox.

Baseball owners were so rattled by the low attendance and lack of enthusiasm for baseball in 1918 that they decided to shorten the 1919 season to 140 games from the normal 154. Almost every team had lost money because of the war; the Yankees and White Sox each claimed a net loss of more than $45,000 in 1918 and, in a rare gesture, White Sox owner Charles Comiskey chose to cut his own salary to $5,000, lower than even those of a handful of his own players. In another attempt to cut costs, National League owners in January 1919 approved an $11,000-per-month player salary cap, which worked out to a team payroll of less than $58,000 in a 140-game season, according to baseball historian Bob Hoie. American League clubs refused to go along with the plan, and even some NL clubs completely ignored it, so the plan was quickly forgotten. The White Sox team payroll on Opening Day 1919 turned out to be $88,461, just under those of the Yankees and the defending champion Red Sox as the highest among all major-league clubs; the Cincinnati Reds were at $76,870, which would have ranked them only sixth highest in the American League.

The owners’ decision to shorten the schedule also had the effect of cutting most players’ salaries, since players were paid only for the time they were in season, from Opening Day to the final scheduled game. For instance, Joe Jackson’s $1,000-per-month contract, which normally earned him $6,000 from the White Sox, came out to only $5,250 in 1919. (Comiskey made it up to him, according to Hoie’s research, with a $750 bonus if he were a “member of the Chicago club in good standing” after the season, thereby bringing his compensation back to the usual $6,000.) Chick Gandil, on the other hand, was paid only $3,500 on his $666.66-per-month contract instead of his usual $4,000 because of the shortened season. He received no bonus, at least not from Comiskey.

The “work or fight” order was the major story in baseball in 1918. With the war looming over their heads all summer, ballplayers who chose to enlist in the military — like future Hall of Famers Ty Cobb and Christy Mathewson — were celebrated for their service to the country. But any able-bodied professional athlete who chose to take a war-essential job rather than enlist, even if his draft status allowed him to do so when he had a family to support, came under heavy criticism from the press and the public.

No one in baseball found himself under more scrutiny in 1918 than the White Sox’ star left fielder, Joe Jackson. Just after the season began, he learned that his draft board in Greenville, South Carolina, had changed his status to 1-A. He had been initially spared from military service because he was married. Instead of waiting for the Army to call his number, Jackson controversially quit the team in May and took a job at a Delaware shipyard, where he and White Sox teammate Lefty Williams (who had left the Sox shortly after Jackson) led the company’s baseball team to an industrial-league championship.

No one in baseball found himself under more scrutiny in 1918 than the White Sox’ star left fielder, Joe Jackson. Just after the season began, he learned that his draft board in Greenville, South Carolina, had changed his status to 1-A. He had been initially spared from military service because he was married. Instead of waiting for the Army to call his number, Jackson controversially quit the team in May and took a job at a Delaware shipyard, where he and White Sox teammate Lefty Williams (who had left the Sox shortly after Jackson) led the company’s baseball team to an industrial-league championship.

Just one day after Jackson left the White Sox, Army Gen. Enoch Crowder began an investigation into the disproportionate number of professional athletes who had suddenly taken “bomb-proof” jobs in the shipyards. Jackson was by no means the only player with a cushy job where his most strenuous duties involved swinging a baseball bat, but he was singled out as a symbol of the “unpatriotic” draft-dodgers who were avoiding combat in Europe. In contrast, Jackson’s teammate Eddie Collins joined the Marine Corps in August 1918, three months before the war ended, and he was widely praised for his service — even though he spent most of his time at a military base in Pennsylvania, a few long fly balls away from where Jackson and Williams were stationed.

Comiskey publicly vowed never to let Jackson or the other “paint and putty league” ballplayers — Williams, outfielder Happy Felsch, and backup catcher Byrd Lynn — play for the White Sox again. Rumors circulated during the offseason that Comiskey intended to trade away one or both of his top outfielders, Jackson and Felsch. At the American League’s annual meeting in December, one month after the armistice was signed to end World War I, Comiskey supported a resolution to blacklist any shipyard players from rejoining the majors. But his stance softened when he realized he would have to rebuild his championship team all over again, and with a nudge from new manager Kid Gleason (who reportedly agreed to take the job only if Comiskey re-signed all of his old players), he soon sent contract offers to Jackson and the others. Still, no one knew how Shoeless Joe would be treated by the fans once the 1919 season began.

The division between enlisted soldiers and shipyard workers wasn’t the only fault line in the White Sox clubhouse. Even while the White Sox were winning the World Series in 1917, they were a team riddled with dissension.

One clique was led by the second baseman Eddie Collins, a college-educated aristocrat from New York whose nickname “Cocky” was well earned. The two rough-and-tumble Californians who flanked him in the infield, first baseman Chick Gandil and shortstop Swede Risberg, hated Collins so much that they reportedly refused to throw the ball his way during practice. Another group on the team consisted of quiet Southerners like Joe Jackson and Lefty Williams, who generally kept to themselves. Collins later said, “There were frequent arguments and open hostility. All the things you think — and are taught to believe — are vital to the success of any athletic organization were missing from (the White Sox), and yet it was the greatest collection of players ever assembled, I would say.”

All of the White Sox starters from their 1917 World Series team had returned to the fold, including pitchers Eddie Cicotte, Lefty Williams, and Red Faber, plus future Hall of Famers Eddie Collins at second base and Ray Schalk behind the plate. Joe Jackson and Happy Felsch anchored the outfield and powered the middle of Chicago’s potent lineup, while Buck Weaver, Swede Risberg, and Chick Gandil rounded out the AL’s best infield.

The faces on the field were familiar, but the manager leading them was new — sort of. On New Year’s Eve, December 31, 1918, owner Charles Comiskey made a surprise announcement that he had dismissed Pants Rowland as manager after four seasons. Rowland had managed the White Sox since 1915 and had steadily improved their place in the standings each year, from third place to second place to a World Series championship. He could hardly be blamed for the sixth-place effort during the tumultuous 1918 campaign. But Comiskey — who had never retained a White Sox manager for longer than four seasons — sensed his veteran team needed a new man in charge.

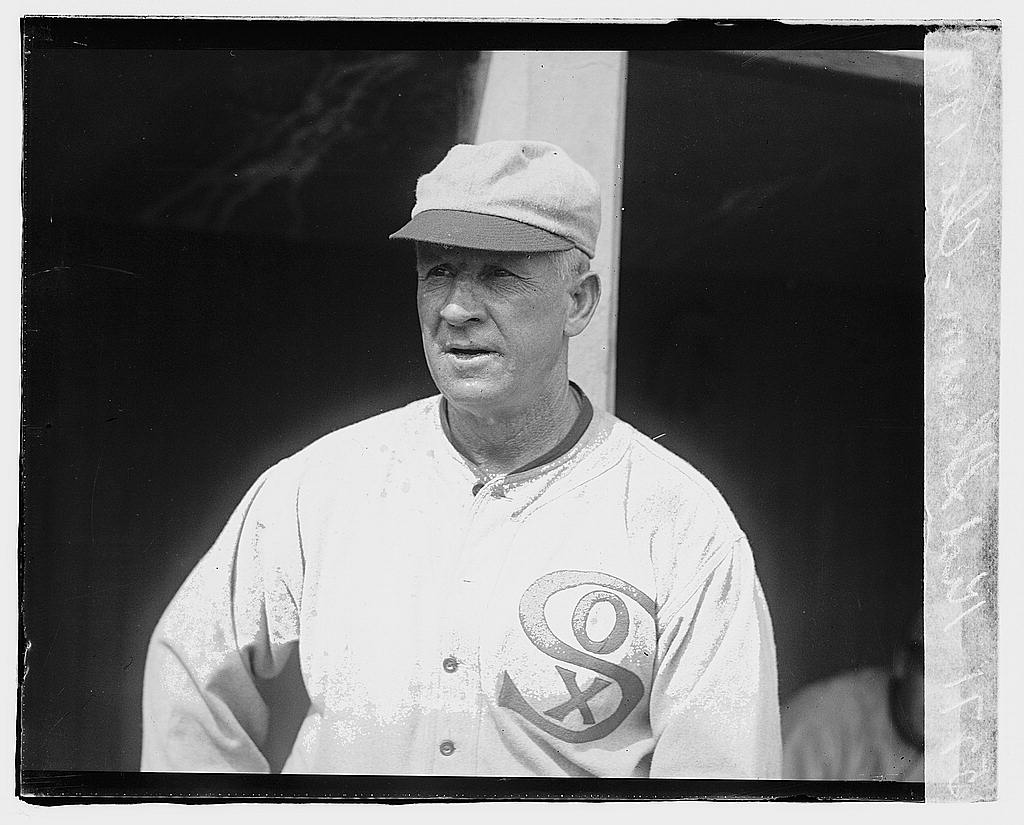

Rowland’s replacement was the White Sox’ longtime coach, William “Kid” Gleason, who had spent more than three decades in baseball but had never managed in the major leagues. The 52-year-old Gleason had been a star pitcher and second baseman around the turn of the twentieth century. As a White Sox assistant coach since 1912 under Rowland and previous manager Nixey Callahan, Gleason had played a key role in developing the team’s young infielders like Weaver, Risberg, and Fred McMullin. The new boss was well liked and respected throughout the game.

Rowland’s replacement was the White Sox’ longtime coach, William “Kid” Gleason, who had spent more than three decades in baseball but had never managed in the major leagues. The 52-year-old Gleason had been a star pitcher and second baseman around the turn of the twentieth century. As a White Sox assistant coach since 1912 under Rowland and previous manager Nixey Callahan, Gleason had played a key role in developing the team’s young infielders like Weaver, Risberg, and Fred McMullin. The new boss was well liked and respected throughout the game.

But like Joe Jackson, Gleason had also quit the White Sox in 1918, sitting out the entire season in what was widely believed to be a financial dispute with Comiskey. On the day Gleason was hired as manager, Comiskey responded to newspaper reports that he had failed to pay Gleason a promised bonus after the White Sox won the 1917 World Series: “Nothing was ever at any time mentioned as to a bonus, and he received everything due him from the White Sox.” (The same accusation against Comiskey was later repeated by some of the banished Black Sox players when they filed lawsuits seeking back pay owed to them.) There is no record of how Comiskey and Gleason finally settled the grievance.

In any case, Comiskey put aside his personal problems with Gleason and hired a manager he felt could get the most out of his veteran ballclub. James Crusinberry of the Chicago Tribune praised the move, writing on January 1, “No one was ever shrewder in a game of ball. … There isn’t a ballplayer in the game today or any of those who played with the Kid in the old days who will not declare him as fair and square a man on and off the ball field as ever lived.”

As the White Sox headed to spring training in Mineral Wells, Texas, no one was quite sure how Gleason’s team would fare in the pennant race. The White Sox’ lack of pitching depth behind Eddie Cicotte and Lefty Williams was cited as a major concern by Chicago Tribune reporter Irving Sanborn, who predicted on April 20, “Unless he has a lot of luck developing new pitchers … (Gleason) is going to have a hard time keeping his team in the first division of the American League.” Veteran Red Faber, who had won three games in the 1917 World Series, was hampered by arm and ankle injuries, and he had come down with the flu virus and could not shake it. A global influenza epidemic had killed more than 600,000 Americans in the winter of 1918-19 alone. Faber’s condition was noticeably weak during spring training and it took him all year to fully recover.

The White Sox had plenty of unproven candidates to take Faber’s place in the pitching rotation. But only Dickey Kerr, a 25-year-old left-hander from Missouri, would emerge from the pack of rookies to contribute to Chicago’s success in 1919. Kid Gleason had to rely heavily on his stars Cicotte and Williams to carry the load, and they were up to the challenge, recording 52 of the team’s 88 wins during the regular season. Even Gleason was a bit surprised at how dependable his top two pitchers turned out to be.

The batting lineup didn’t have much depth, either — only Fred McMullin and Shano Collins received significant playing time among the reserves — and if not for the normal aches and pains and slumps over the course of a long season, Gleason would have been happy penciling in the same eight starters every day in this order:

- Nemo Leibold, RF

- Eddie Collins, 2B

- Buck Weaver, 3B

- Joe Jackson, LF

- Happy Felsch, CF

- Chick Gandil, 1B

- Swede Risberg, SS

- Ray Schalk, C

For a franchise long saddled with the nickname “Hitless Wonders,” these White Sox had a powerful offensive attack. They would go on to lead the American League in hits, runs scored, and stolen bases. Jackson batted .351, fourth highest in the AL, and finished among the league leaders in slugging, on-base percentage, RBIs, and total bases.

As the White Sox took the field for Opening Day on April 23, 1919, against the St. Louis Browns at Sportsman’s Park, it quickly became apparent to the rest of the American League that all the preseason fears about their chances were premature. Chicago’s 13-4 win behind Lefty Williams’s complete-game effort and Joe Jackson’s three hits showed that the Sox were back in championship form. Manager Kid Gleason never stopped worrying about his over-reliance on Williams and Eddie Cicotte and continued to look for pitching help wherever he could find it, but for now, the season’s outlook appeared extremely bright.

JACOB POMRENKE is SABR’s Director of Editorial Content, chair of the Black Sox Scandal Research Committee, and editor of “Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox” (2015).

Sources

“Bombproof Jobs of Ball Players Due For Probing,” Chicago Tribune, May 16, 1918.

“Commy Tells His Side of the Felsch Story,” Chicago Tribune, January 1, 1919.

Crusinberry, Jim. “Kid Gleason Appointed Manager of the White Sox,” Chicago Tribune, January 1, 1919.

Deveney, Sean. The Original Curse: Did the Cubs Throw the 1918 World Series to Babe Ruth’s Red Sox and Incite the Black Sox Scandal (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009).

Hoie, Bob. “1919 Baseball Salaries and the Mythically Underpaid Chicago White Sox.” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Spring 2012).

Huhn, Rick. Eddie Collins: A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2008).

James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Free Press, 2001).

Leeke, Jim. “The Delaware River Shipbuilding League, 1918,” The National Pastime: From Swampoodle to South Philly (Phoenix, Arizona: Society for American Baseball Research, 2013).

Sanborn, Irving. “Baseball Races Start on Wednesday,” Chicago Tribune, April 20, 1919.