Polo Grounds (New York)

This article was written by Stew Thornley

The Polo Grounds, an odd name for an odd stadium, was home to several baseball teams, most notably the New York Giants until the team moved to San Francisco following the 1957 season. Its horseshoe-shaped grandstand and elongated playing area provided for ridiculously short distances down the foul lines and equally ridiculous long distances to the power alleys and center field. So short were its foul-line distances that inches were sometimes included in the measurements — 279 feet, 8 inches to left; 257 feet, 8 inches to right. As for the distance to center, the figure almost could have been rounded to the nearest hundred.

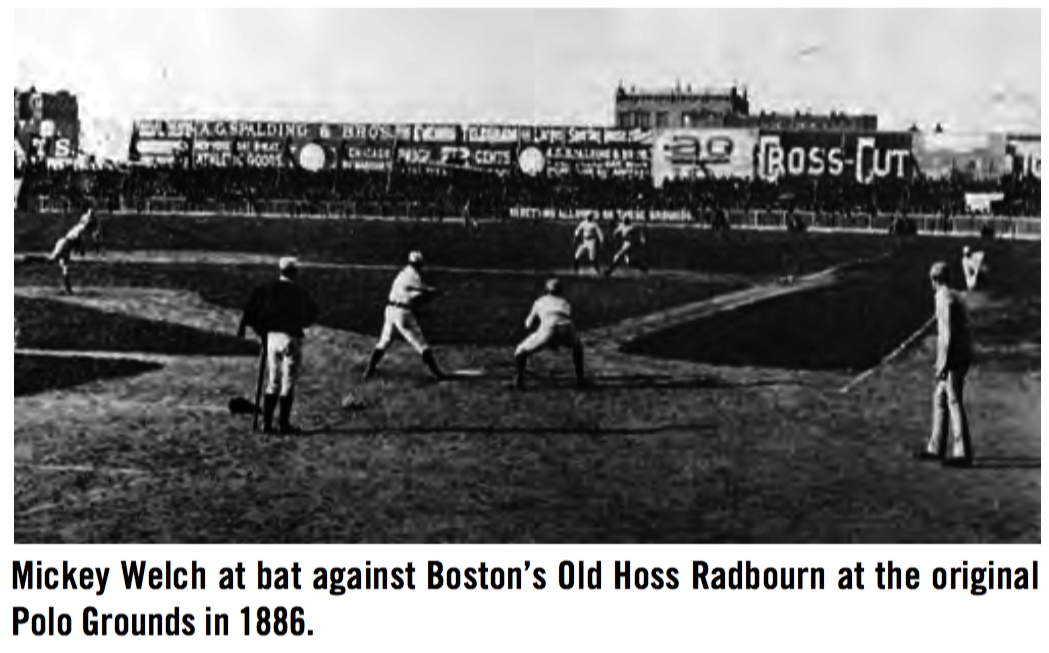

The Polo Grounds is actually the story of several stadiums. The final three were located beneath Coogan’s Bluff in upper Manhattan. But there was another location for the original Polo Grounds, the first stadium to use the name and the only one on which polo was actually played, at the corner of 110th Street and Fifth Avenue, just north of Central Park.

It wasn’t until 1880 that professional baseball was played in Manhattan. The first site was a polo field in the midst of what was then a fashionable neighborhood dominated by aristocratic apartment houses and brownstones, just north of the northeast corner of Central Park. Although New York had been represented in the National League’s inaugural year of 1876, the team that carried the city’s name actually played its games in the still-independent city of Brooklyn, across the East River from New York.

In 1880, a team called the Metropolitan was formed as a result of a partnership between John B. Day, a wealthy young merchant and Tammany politician who preferred to think of himself as a baseball player, and Jim Mutrie, a man without Day’s financial means but with a greater understanding of baseball.

Mutrie had been playing on a Brooklyn-based team and aspired for more. He wanted to manage, and he also fretted over the hordes of potential fans in New York who wouldn’t make the effort to come to Brooklyn. The only access between the two cities was via a ferry. Cathedral arches were taking shape on the masonry towers of a bridge that was under construction, but completion of this span was still several years away.

Rather than worry about how to get the fans from Manhattan Island to Brooklyn, Mutrie decided to do it the other way around. He decided the ideal spot for baseball in New York was on the grounds being used for polo at 110th Street. He approached the polo club and secured a lease on the grounds for baseball — if he could get a financial backer.

Mutrie then began the task of attempting to persuade some of the city’s upper crust to invest a small portion of their fortunes in a baseball team. His efforts paid off when he met Day. With Day’s money, Mutrie began to stock a roster with players from Brooklyn as well as the Rochester Hop Bitters, which had recently disbanded. Soon Mutrie had a squad of professionals.

The Metropolitans (normally referred to in the plural form even though Day and Mutrie intended the name to be singular) were an independent team, not affiliated with any league. They devised a schedule that would pit them against National League teams, once the League season was over. In the meantime, the Metropolitans played against a collection of top amateur teams, including those from local colleges, and other independent professional teams.

Work was underway to lay new drains and erect a grandstand on the Polo Grounds, but the facility wasn’t ready as soon as Mutrie and Day had hoped. Instead, the Metropolitans continued playing at the Union Grounds in Brooklyn, the team’s first game occurring on Thursday, September 15, 1880.

The first game on the Polo Grounds was scheduled for Wednesday, September 29 against the Nationals of Washington, the team that a month earlier had been making the rounds in Brooklyn. More than 2,000 fans turned out for the first professional baseball game in New York City. They almost went home disappointed as the Nationals didn’t show up on time. Finally, more than a half-hour after the game’s scheduled start of 3:30, the Nationals arrived through the Sixth Avenue gate. The late start made it impossible to complete nine innings, but the Metropolitans, behind the pitching of Hugh “One Arm” Daily, defeated the Nationals, 8-3, in six innings. (Some sources place the final score as 4-2, not bothering to count the runs scored by both teams in the last inning played, which was cut short by darkness.)

Over the next month, the Metropolitans played National League teams, primarily at the Polo Grounds, although scheduling conflicts (including some polo matches) forced the team to return to the Union Grounds in Brooklyn as well as a field in Hoboken, New Jersey. However, John B. Day was able to work out arrangements with the Manhattan Polo Association which would leave the field on 110th Street free for baseball starting the following season.

In 1881 and 1882, the Metropolitans continued playing a mix of amateur and professional opponents, including National League teams whenever possible. The team remained independent during this time despite an invitation to join a newly formed major league, the American Association, in 1882.

A series of events following the 1882 season resulted in New York getting teams in the American Association and in the National League. It began when two teams, Troy and Worcester, were forced to resign their memberships in the National League, leaving the league a pair of openings for the 1883 season. One of the vacant spots was filled by Philadelphia; it was expected Day would fill the other by entering the Metropolitans in the National League.

But instead, Day accepted the American Association’s offer to the Metropolitans, a year after it had first been offered, and also announced he would produce a team from scratch for the National League. He turned to the defunct Troy team and picked off its top players. The very best he kept for his National League team; the next echelon were relegated to the Metropolitans.

From this, the first of several baseball stadiums named the Polo Grounds was about to serve as the home to two major-league teams, the first to play their home games within the confines of New York City.

By this time the Polo Grounds was by this time no longer being used for polo. Baseball was the only sport on the site, and the grounds contained a lavish and expansive double-decked wooden grandstand in the southeast corner of the rectangular lot, near the intersection of 110th Street and Fifth Avenue. Including the bleachers that extended beyond the grandstand down the left- and right-field lines, the Polo Grounds had as many seats as any stadium in baseball at that time.

Major-league Baseball on the Polo Grounds

The New York teams prepared for the 1883 season with a series of exhibition games in April. Because of a peace accord between the two leagues, reached only two months before, pre-season games between National League and American Association teams were allowed. As a result, the New-Yorks and Metropolitans played eight games on the Polo Grounds. More than 5,000 fans turned out for the first game between the teams.

But that crowd was puny compared to the turnout two-and-a-half weeks later when the National League season opened on the Polo Grounds with a game between New York and Boston on Tuesday afternoon, May 1. The gates of the Polo Grounds opened at 2:00, and a stream of humanity poured in. By the time the game began two hours later, the crowd was in excess of 15,000, including former president Ulysses Grant. (The New York team later adopted the nickname of Giants. It has been reported that the club had been originally called the Gothams, although this name was not used in newspaper accounts, which referred to the team as the New-Yorks.)

The New-Yorks beat Boston 7-5 in their initial game on the Polo Grounds (newspapers more often referred to games on the Polo Grounds rather than at the Polo Grounds), but the Metropolitans, managed by Jim Mutrie, didn’t fare nearly as well in their home opener.

The first problem concerned the team’s playing area. John B. Day’s plan to solve the issue of having two major league teams but only one field was to carve out separate diamonds at opposite ends of the field. He intended on having the New-Yorks play on the diamond in the southeast corner and the Metropolitans on a diamond toward the southwestern corner of the lot.

However, the southwest diamond and grandstand still weren’t ready for the Metropolitans’ scheduled home opener on Saturday, May 12. The Metropolitans instead played on the southeast diamond, before a crowd only one-fifth the size of that at the opener for the New-Yorks and were battered by the Athletic Club of Philadelphia, losing 11-4. Over the next two-and-a-half weeks, the Metropolitans continued to play their home games on the southeast diamond while work continued on the southwest diamond.

The Polo Grounds were being used for all types of baseball events at the time. On the rare days that neither the National League nor American Association team was using the grounds, college and other amateur teams played there. (This continued through later versions of the Polo Grounds. Colleges, high schools, and a number of other amateur teams were allowed use of all the stadiums that bore the Polo Grounds name. In September 1947, the New York Times even listed an upcoming charity baseball game with the “Arm Amputees vs. Leg Amputees.”)

Near the end of May 1883, a special exhibition took place with the Metropolitans facing a picked nine (a group of individual players assembled for a particular game rather than an already intact team). A crowd of 4,000 turned out, mainly to see the pitcher the Metropolitans would be using, bareknuckle heavyweight champion John L. Sullivan. “Sullivan has always been identified with base-ball,” reported the New-York Times, “and at one time was a promising player. He has been practicing curves and up and down shoots lately, and it is said they will prove as effective as his round hitting.” For his performance, Sullivan received 50 percent of the gate receipts, although many wondered if he actually earned his keep. Sullivan did not attempt to pitch hard, claiming he was afraid of spraining his arm. The New-York Tribune reported, “The contest was a farce from beginning to end and the crowd was thoroughly disgusted. … Sullivan’s delivery was neither swift, accurate, curved, nor effective.” Nevertheless, Sullivan continued to pitch, and draw large crowds, in exhibitions in the Northeast the rest of the season.

Usually baseball games on the Polo Grounds took place one at a time. However, during a two-week stretch beginning May 30, Decoration Day (the original name of Memorial Day), both the New-Yorks and Metropolitans were at home. Fortunately, the western diamond was finally ready for occupancy by this time, although the Metropolitans quickly learned that it was a far inferior playing area (with some of the tract reportedly leveled with the use of raw garbage as landfill).

However, the Metropolitans had little choice because five games — involving five major league teams and two college squads — were scheduled for the Polo Grounds on Decoration Day, and two diamonds would be necessary to accommodate all the games.

The Metropolitans started the long day of baseball with a 9:30 a.m. game against Cincinnati, a contest that marked the opening of the west diamond at the Polo Grounds. A half-hour later, just a bit to the east, the New-Yorks began a game against Detroit.

When the National League game was over, Yale and Princeton took the field on the east end for a game to decide the college championship. Upon its conclusion, the New York and Detroit teams returned for the second game of their doubleheader. Meanwhile, the Metropolitans — who had eked out a 1-0 win over Cincinnati in the morning game — were beating Columbus, 12-5, completing a doubleheader sweep over two different teams.

The crowds were sparse for the early games, but fans came and went over the course of the day and, in all, upward of 10,000 fans turned out at some time to see some of the baseball at the Polo Grounds on Decoration Day.

In an attempt to quell some of the confusion of simultaneous games, John B. Day had a flimsy, canvas-covered fence erected to separate the playing areas. This portable fence remained up through June 14, during which time the New-Yorks and Metropolitans continued to play on opposite ends of the same grounds at the same time.

The Metropolitans then left on a long road trip and didn’t return to the Polo Grounds until July 23. By this time, the New-Yorks were ready to begin a road trip. Both teams were at home in August, but usually at different times.

At the end of August, though, the schedule once again called for a brief stretch when both New York teams were to play at home at the same time. The portable canvas-covered fence was reinstalled as games were played simultaneously on the opposite diamonds.

Under rules of the day at the Polo Grounds, balls rolling under the fence remained in play, causing the bizarre scene of an outfielder emerging into the opposing field in pursuit of a ball. Although outfielders proved agile and adept at getting under the fence and to the fugitive balls, occasionally a hit that rolled under the fence ended up as a home run.

In addition, the canvas fence restricted the field of play to the point of producing some cheap over-the-fence home runs. A few batters even adjusted their batting style to take advantage of the easy reaches. Of the August 30 game between the New-Yorks and Boston, the New-York Tribune said, “‘Sky-scrapers were more numerous than ‘daisy-cutters’ … There was little scientific place batting. The adjustable fence separating the League from the American Association field again retarded the movements of the players, and some of the runs would never have been made had the grounds been larger. The Polo Grounds are sufficiently large for one game of baseball, but not nearly large enough for two games to be played at once.” In this game, Boston’s John Morrill came to the plate with two runners on in the first inning and sent a drive — one that might have been catchable had New York left fielder Pete Gillespie had unlimited room to roam — over the barrier in left-field for a three-run homer. The next day, John Montgomery Ward of the New-Yorks countered with a similar drive for a home run. A few days later, the canvas-covered fence was removed for good.

Neither the New-Yorks nor the Metropolitans challenged for their league title, although the Metropolitans did finish in fourth place, two spots higher than their counterparts in the National League.

[Author’s Note: I am still unclear on how often the west diamond on the Polo Grounds was used by the Metropolitans in 1883 — if it was normally used by the Metropolitans or if it was used only when there was a scheduling conflict on the east diamond because the New-Yorks were at home at the same time. Some researchers maintain that the Metropolitans normally used the east diamond and moved to the west diamond only on 12 different dates when there was a conflict on the east diamond. However, I am not convinced this was the case. It seems that the original intention of John B. Day (who owned the Metropolitans as well as the New-Yorks) was to have the Metropolitans play regularly on the west diamond in 1883. This is based on reports from the New York Clipper during the first three months of 1883 in addition to an item that appeared in The World (New York) Saturday, May 12, 1883, the date of the Metropolitans first regular-season home game. The World reported that the Metropolitans were playing their home opener on the east diamond because the west diamond was not yet ready, implying that they would be using the west diamond regularly when it became available. However, it is possible that the Metropolitans — after their first round of games on the west diamond, from May 30 to June 14 — were so discouraged by the condition of the field that Day decided to abandon the west diamond, use it only when there was a conflict (as there was again later in the season, between August 30 and September 4), and have the team play most of its games on the east diamond. It is clear that the first games were played on the west diamond on Decoration Day, May 30; it is also clear that, regardless of the situation, that the portable fence was used to separate the two playing areas only during the period when both the Metropolitans and New-Yorks were home at the same time.

In The Beer and Whisky League, David Nemec’s history of the American Association, Nemec reported that the west diamond was used by the Metropolitans for only 13 games in 1883. Nemec received this information from Bob Tiemann, another outstanding SABR researcher, who said that an advertisement appeared in the New York papers each day there was a baseball game during the season and that the ad specified which side of the Polo Grounds that fans should use for the entrance. If it said the Fifth Avenue side, it meant the game was on the east diamond; if it indicated the Sixth Avenue side, it meant that the game was on the west diamond. However, the only time the ads were ever this specific was when both New York teams were playing at home and both diamonds were occupied. In those situations, the answer is already known — the Association played on the west diamond, the National League on the east. Still unanswered is the question of which diamond was used for Metropolitan games when they were the only team hosting a game on the Polo Grounds after the west diamond became available on May 30. On these dates, the newspaper ads did not specify which side of the Polo Grounds the fans should use for entry.

Even though others claim to know the answer to this question, I remain skeptical and view this as an unsolved mystery of the Polo Grounds.]

The Metropolitans started the 1884 regular season in a different stadium. Complaints from visiting teams about the arrangements on the Polo Grounds in 1883, along with a desire by Association officials to have the team loosen its ties with the New York National League franchise, prompted the American Association to order the Metropolitans to find a new stadium. Over the winter, John B. Day settled on a site between 107th and 109th streets along the East River and had the lot prepared for baseball. It would be accessible by the Second and Third Avenue elevated lines as well as by water as arrangements were made with the Harlem Steamboat Company to stop at landings near the ballpark on days games were being played.

Rather than being a step up, however, the move was a distinct step down. Metropolitan Park, as the new stadium was named, was built on a site formerly occupied by the city dump. It proved to be such a foul location that it made even the west diamond of the Polo Grounds look like a palace. The malodorous conditions at the games proved too much for fans to endure and the crowds became sparse. After only five weeks, Day gave up on Metropolitan Park as the regular home for his team. When the Metropolitans returned from a month-long road trip in mid-July, they moved back onto the Polo Grounds.

The southwest diamond at the Polo Grounds was no longer being used, and the Metropolitans began sharing the southeast diamond with the New-Yorks. However, there were a few scheduling conflicts on the Polo Grounds during the remainder of the 1884 season; when this happened, the Mets ended up going back to Metropolitan Park.

Despite the turmoil, the Metropolitans won the American Association pennant and then lost to the Providence Grays, champions of the National League, in a postseason series. (Although the champions of the American Association and National League had met in a post-season series in 1882, this 1884 matchup between the Metropolitans and the Grays was considered the first “World’s Series” that was sanctioned by both leagues. It continued through most of the remaining seven years of the American Association’s existence, although there was never a fixed system for the format of the series; the number of games — which ended up as high as 15 — were determined each year by the champion teams and the locale was not restricted to the home fields or cities of these teams.)

Even though the Metropolitans had been swept in the World’s Series by Providence, Day was pleased with their play and felt he had a good team on his hands — too good, in fact, to be playing in a league that charged only a quarter for admission. He decided to consolidate his best players on his National League team, for which he could charge the citizens of New York 50 cents for the privilege of watching.

The Mets and New-Yorks shared the Polo Grounds again in 1885. Normally, one team was playing elsewhere when the other had a game at home, but, as had happened the previous two seasons, there were a few occasions when both were scheduled for the Polo Grounds. In 1883 the conflicts had been resolved by having the western diamond on the Polo Grounds for use by the Metropolitans and in 1884 by having the team go back to Metropolitan Park. In 1885, though, the Metropolitans and New-Yorks shared the Polo Grounds on the same day by playing doubleheaders. The Metropolitans would play their opponent at 1:45 or 2:00 with the New-Yorks following with their game. The pace of games was much more rapid in the 1800s, and it was normally possible for both games to be completed with existing daylight, even late in the season and even though daylight savings time was more than three decades away. Fans enjoyed the opportunity to see both teams for one admission, even though they had to pay the usual National League admission of 50 cents rather than the cut-rate Association fee of 25 cents.

The fortunes of the two New York teams reversed itself in 1885. Robbed of its stars, the Metropolitans languished. The recipient of those stars, the New-Yorks were able to compete for the National League pennant for the first time, although they fell short and finished two games behind the champion Chicago White Stockings.

The Giants (as they were by this time known) were the team to see in New York, and there was little room for another, especially a decimated group like the Metropolitans. At the end of the 1885 season, the Metropolitans were sold to a man named Erastus Wiman, who operated the Staten Island ferry and owned an amusement park on Staten Island. Over the next two years, before the team was completely dissolved, the Metropolitans played their games at a facility within the amusement park called the St. George Cricket Grounds.

The Giants were successful during this period and, in 1888, won their first National League pennant to advanced to the World Series, against the St. Louis Browns of the American Association. New York beat the Browns, 6 games to 4, in a series played in New York, St. Louis, Brooklyn, and Philadelphia. Four of the first five games of the series were played in New York and turned out to be the final games ever played on the original Polo Grounds.

For some time, there had been indications that the city might be planning on extending 111th Street, which at this point had been interrupted by the Polo Grounds between Fifth and Sixth avenues, through the site occupied by the Giants. John B. Day, a man familiar with the workings of New York City politics, had been able to hold off the move for a while (reportedly through yearly bribes of season tickets to the Board of Aldermen), but in early 1889 the city announced it would proceed with its plans. Day made a few efforts to further delay the demise of the Polo Grounds but finally gave up.

One-hundred-eleventh Street ended up going right through the heart of the field, and the elaborate grandstand was torn down and replaced by a traffic circle — one eventually named for public administrator James J. Frawley. Meanwhile, the Giants were left to seek new quarters as the 1889 season approached.

New Location, Same Name

Having still not settled on a permanent location for his Giants by the time the 1889 season opened, John B. Day arranged for the use of a ballpark across the Hudson River in Jersey City, New Jersey. After only two games there, though, Day moved the team to another set of temporary quarters, the St. George Grounds on Staten Island, the same facility used by the Metropolitans in 1886 and 1887.

Finally, on Friday, June 21, Day settled on a location just off the Harlem River in the southern half of Coogan’s Hollow in Manhattan, a lot that ran 400 feet west beneath the 155th Street viaduct and 460 feet north along Eighth Avenue. Even though he didn’t need it at the time, Day was considering leasing more land from the Lynch estate, owners of the property. By the end of the season, he would lament the fact that he hadn’t.

Day was concerned about confusion that might be present with fans as the team prepared for its third home of the season. He knew that New Yorkers associated the name Polo Grounds with his baseball team, so — to send an unambiguous message as to where the Giants would be headquartered — he christened the quarters the New Polo Grounds. The sport of polo had never been — nor ever would be — played on this site, but nonetheless the name endured. (In keeping the familiar name, Day started a New York trend later followed when the name Madison Square Garden persevered with arenas built away from the vicinity of Madison Square.)

The entrance to the New Polo Grounds was approximately 40 feet from the stairway of the Eighth Avenue elevated station on 155th Street. Access to the area was good enough for a huge throng to turn out for the first game at the New Polo Grounds, on Monday, July 8 (barely more than two weeks after work had begun to convert the field into a stadium). Over time, the facility became more elaborate, and it eventually featured a double-decked grandstand behind home plate and a large clubhouse behind first base. In addition, the area under the third-base grandstand included horse stables.

In keeping with the other stadiums that had and would bear the same name, the Polo Grounds at 155th Street and Eighth Avenue was oddly shaped. Narrow on the western end and bulging toward the east, the playing area resembled a pear. Home plate was in the southern part of the lot with first base extending toward the Harlem River and third base toward Coogan’s Bluff. The outfield featured a embankment running from center toward right field. Outfield embankments were not unusual in early baseball stadiums, but this one stood out because of its size and steep pitch. It created difficulty for the outfielders who had to patrol the area, particularly when rains made the embankment muddy and the footing treacherous.

Such was the case in the season’s final regular-season game at the Polo Grounds, September 14, 1889, when Chicago’s Capt. Adrian Anson hit a long drive to center. The ball, rather than roll back down, stuck in the top of the embankment, which was too slick for New York center fielder George Gore to climb. Unable to get up to the ball, Gore watched helplessly as Anson circled the bases with a home run. However, the Giants still won the game and continued their winning ways as they went on the road the following week, finally moving into first place ahead of Boston. The two teams stayed close to one another the rest of the way, with the Giants finally pulling out the pennant on the final day of the regular season and then winning the World Series against Brooklyn, champions of the American Association.

Although John B. Day rejoiced in another world title, he was concerned about events taking place off the field. A new league was in the process of forming, the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players, an organization with its roots among members of the New York Giants. The Brotherhood had been formed in 1885, as a means of thwarting a salary cap plan the National League owners attempted to implement, with John Montgomery Ward of the Giants elected as Brotherhood president and New York pitcher Tim Keefe as its secretary. The Brotherhood and the National League were able to co-exist over the next few seasons, but in 1889 — in response to further abuses by the owners — Ward and his followers made plans to form a league of their own for the following season.

News of the rebel league broke in September of 1889, while the Giants and Boston were fighting for the pennant. On top of that, James J. Coogan revealed that “capitalists and men interested in the New York Club [slated for the new league] have approached him with offers to lease certain lands just north of the Polo Grounds for baseball purposes.”

No doubt John B. Day was sorry he had not leased the northern portion of Coogan’s Hollow when he had the chance; instead, it ended up in the hands of the owners of the New York team in the Players’ League, which the new organization was called. The backers, Edward A. McAlpin and Edward B. Talcott, began work on a new baseball stadium, Brotherhood Park, next door to the Polo Grounds.

The 1890 season in New York opened with games being played simultaneously in the adjacent stadiums, Brotherhood Park to the north and the Polo Grounds to the south. Fans demonstrated which version of the game they wanted to watch. With many of the Giants stars now on the New York Players’ League team, larger crowds turned out in the northern ballpark. The New-York Times reported the attendance at Brotherhood Park as 12,013, well more than the crowd of 4,644 at the Polo Grounds for the National League game.

Stripped of its top players, the National League Giants finished in sixth place. The team still had a few stars and provided a few exciting moments for the fans, few as they might have been, who did turn out. On Monday, May 12, the National League teams of Boston and New York staged a tremendous battle that was enjoyed by the 687 fans at the Polo Grounds in addition to some of the 1,707 fans who came to watch the Boston and New York Players’ League teams play in Brotherhood Park.

The game at the Polo Grounds featured a pair of young pitchers now in the Hall of Fame: 20-year-old Kid Nichols for Boston and Amos Rusie, who was approaching his 19th birthday. The game remained scoreless through 12 innings as both the pitchers and fielders shined. As the Giants came to bat in the top of the 13th inning (the home team having its choice of whether to bat or take the field first at that time), they had some additional spectators. Some in the crowd at the Players’ League game had gotten wind of the duel unfolding next door. They moved to the top of the bleachers on the south side of Brotherhood Park, where they could peer over the fences and into the Polo Grounds.

After Nichols struck out Rusie to start the 13th, Mike Tiernan broke up the shutout with a tremendous drive to center field that cleared the fence of the Polo Grounds, landing in the narrow alley that separated the two ballparks, and bounding up against the outer fence of Brotherhood Park. As Tiernan circled the bases with what would be the only run of the game, he received lusty cheers from fans in both parks.

Coogan’s Hollow was a busy spot for baseball in the summer of 1890 with teams from two different leagues making their home there. In addition, a new Brooklyn team in the American Association (one that replaced the Brooklyn Bridegrooms, who had jumped to the National League and were in the process of winning a league pennant for the second-straight year), the Brooklyn Gladiators, used the Polo Grounds for some of its home games in late July and early August.

A treaty of sorts was established following the 1890 season between the National League and Players’ League, bringing about the elimination of the latter. The rebel organization left a number of legacies, including the financial ruin of John B. Day and a new ballpark for the Giants.

Having lost his fortune fighting to keep the Giants afloat and the National League together, Day was forced into an alliance with the men who had backed the Brotherhood efforts in New York. Although Day remained briefly as president of the team, his power was all but gone. The new group of owners decided that Brotherhood Park, now without a tenant, was the superior facility in Coogan’s Hollow and moved the New York National League team into it for the 1891 season. The Giants were making another move uptown, although this one was only a matter of feet rather than blocks. And, once again, with the Giants came the name of their stadium. Brotherhood Park was renamed the Polo Grounds.

The New Polo Grounds (which thus became the old Polo Grounds) on 155th Street reverted to the previous name, Manhattan Field, and was leased to Andrew Freedman, another man with Tammany Hall connections who would eventually take over the Giants.

At Manhattan Field, the grandstand that had been built for the Giants remained through the decade. Even after it became nothing more than a vacant lot, it remained the site of cricket matches and other sporting events as well as serving as a parking lot for the Polo Grounds. Although Giants’ management leased the parcel to other interests for a variety of uses, the team — with a fresh memory of the 1890 interlopers building a ballpark next door — retained control of the property to ensure such an event never happened again.

Polo Grounds III

Polo Grounds III was changing even before it became the Polo Grounds. During the 1890 season — when it was still Brotherhood Park — the stadium was undergoing a massive makeover that increased its capacity and redefined its dimensions.

Two small bleacher sections were erected in center field while other bleacher sections, those reaching out from the grandstand, were extended into fair territory. The result was a reduction of the distances down the foul lines — from 335 feet to 277 feet in left field and from 335 feet to 258 in right field. Center field remained approximately 500 feet from home plate, far enough away that the well-to-do could park their horse-drawn carriages beyond the ropes that delineated the playing area and watch the game from there. With these modifications, and the takeover of the stadium by the National League Giants, Polo Grounds III became the first of the so-named stadiums to assume the distinctive horseshoe shape.

The grandstand was double-decked, with the roof supported by Y-shaped posts, and curved around home plate and approximately 20 feet past first base and third base. For a time in the early 1900s, the configuration of the diamond was such that a portion of the curving grandstand protruded across the foul line and into fair territory in right field. A white line was painted on the front fence of the curving grandstand with a pole erected on the far edge of the stands. The line and the pole, in line with one another, served as markers to separate fair from foul territory. Beyond this protrusion was an alcove, used for the bullpen, with the outfield bleachers (which contained still another foul pole) beyond the alcove. Balls hit into the fair territory portion of the bullpen alcove were in play. Balls hit along the same path but not as far could land in the portion of the grandstand protruding into fair territory. The batter would not receive a home run for his efforts, however, since the rules dictated a minimum distance of 235 for an over-the-fence home run; instead the drive would result in a double. Still, the protruding grandstand was a strange feature that made it possible for a ball to be hit too far to be a double.

The first National League game in Polo Grounds III was played on Wednesday, April 22, 1891, and a huge crowd was on hand to see the Giants reunited. Before the game, Giants who had remained with the National League team lined up on one side of the field with those who had gone to the Players’ League on the other. The two sides then came together to indicate that past differences were settled and that they were one team again. The Giants put on a good show for their fans in 1891, rising to a third-place finish (after having dropped to sixth place the previous season).

The American Association, which had operated as a major league since 1882, disbanded after the 1891 season. The National League absorbed four of the Association teams, swelling its ranks to 12. The league scaled back to eight teams around the turn of the century; by this time, the Giants were among the National League’s bottom feeders. But events were transpiring that would bring about a dramatic turn-around for the occupants of the Polo Grounds.

John McGraw arrived as manager in July of 1902, and the Giants built a great team around Christy Mathewson, a righthander who would win at least 30 games each season between 1903 and 1905, going on to a career total of 373 wins. New York rose from last place in 1902 to second in 1903. The following year, the Giants won 106 games to capture their first National League pennant since 1889. The team refused to play Boston, champions of the American League (now in its fourth season as a major league), in a post-season series, but this snubbing of the upstart league brought about the drafting of a format for a regular post-season meeting between the champions of the American and National leagues. The first official World Series was played in 1905, and the Giants — repeating as pennant winners in the National League — played in it against Connie Mack‘s Philadelphia Athletics. The Giants won the series, four games to one, with all five games being shutouts. Mathewson was the star, winning three of the shutouts to put the Giants on top again and make the Polo Grounds the capital of the baseball world.

A bizarre event, forever after known as “Merkle’s Boner,” occurred at the Polo Grounds in September of 1908 and may have cost New York another appearance in the World Series. The National League had a great three-team race between the Giants, Pittsburgh Pirates, and Chicago Cubs. The Cubs and Giants, in a virtual tie for first place, met on September 23 in a game that was tied in the last of the ninth. The Giants had Moose McCormick on third and rookie Fred Merkle on first with two out when Al Bridwell singled to center, bringing in McCormick with the winning run — or so it appeared. Merkle headed for the clubhouse without bothering to touch second. This practice was customary at the time as players tried to get off the field ahead of fans, who came out of the stands and crossed the field to exit the stadium. However, in this instance, a mad scene took place as infielders Frank Chance and Johnny Evers attempted to get the ball thrown in from the outfield. With fans swarming onto the field and some of the Giants catching wind of what the Cubs were up to and trying to stop them, it is unclear exactly what happened and when. But somehow, Evers got a hold of a ball (whether or not it was the same ball Bridwell hit is anybody’s guess) and stepped on second base, claiming a force out. Umpire Hank O’Day withheld his ruling until he was in the safety of his dressing room. Once there, however, he sided with the Cubs, calling Merkle out. With fans still swarming on the field, and with darkness setting in, it was too late to resume play, so the game ended as a 1-1 tie.

The game was replayed in its entirety at the conclusion of the season. With the teams again tied for first, the victor would advance to the World Series. Perhaps never before had there been such interest in seeing a baseball game. The Giants management even had watchmen on patrol the previous evening to prevent the bleachers from filling up overnight. The police also anticipated the need for crowd control for the event, but no one — not the team, not the newspapers, not the police department — came close to predicting the size of the throng that came for the game, nor the determination of those in the crowd to see it.

In the game, the Cubs got to Mathewson for four runs and held on for a 4-2 win to take the pennant. Depending upon the accuracy of estimates provided by the various New York newspapers, anywhere from 80,000 to 100,000 fans showed up and attempted — successfully or otherwise — to see the game.

The Giants opened the 1911 season at home with a pair of losses to the Philadelphia Phillies. Shortly after midnight the next morning, Friday, April 14, a fire began in the lower timbers of the grandstand. A brisk wind from the southeast swept the fire over the grounds and with an hour, most of the structure was ablaze with flames leaping nearly 100 feet in the air. The first alarm was issued at 12:40, but by this time the fire had swept around the entire circle of grandstand seats and was spreading to the storage yards of the elevated lines that adjoined the stadium on the north.

By 2:00 the fire was under control, but all that remained of the Polo Grounds were some bleachers in left field and the clubhouse/office building at the Eighth Avenue end, which were saved because they were separated by a gap from the portions of the stadium that were on fire.

A Grand New Stadium

The future of baseball beneath Coogan’s Bluff was in jeopardy following the fire. But a more immediate concern dealt with where the Giants would play their home games while plans were developed and implemented for a new stadium. The owners of the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Highlanders (unofficially and soon to be officially the Yankees) offered the use of their ballparks, and Giants owner John T. Brush accepted the latter as the team directors began dealing with the questions regarding the construction of a new facility.

Brush was determined to build a new stadium with the latest in materials and design and had Osborn Engineering Company — a Cleveland firm that made its mark as the designing and structural engineers in many stadiums built in the first quarter of the 20th century — in town within days of the fire, starting plans for a stadium to be built on the same site as the previous one, even though he still had the issue of a long-term lease to consider. (The current lease with the Coogan estate, signed the year before, was for only ten years. ) Within two weeks, however, that matter had been resolved as the Giants agreed to a 25-year lease.

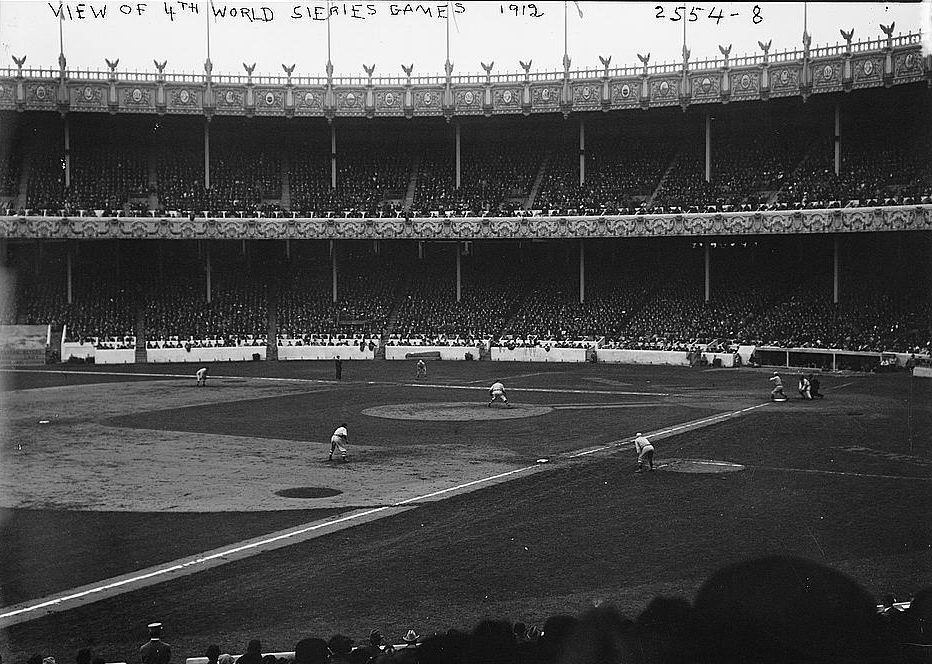

The new stadium was to be patterned after the new wave of recently opened or remodeled ballparks that had steel and reinforced concrete as their primary building materials, a list that included Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, League Park in Cleveland, Shibe Park in Philadelphia, and Comiskey Park in Chicago. Although other teams were constructing impressive edifices, John Brush had ambitions for a stadium for the Giants that would surpass all others in terms of size, structure, and design. His wishes were carried out. The substructure of the new stadium consisted of spread, reinforced concrete piers rising to the level of the first tier of seats. This tier was built of reinforced concrete in the form of a great slab supported by girders across the piers. Construction above the first tier was open steel framing with the upper deck and roof cantilevered out.

Although described as “utilitarian” by Henry B. Herts — the architectural designer who designed numerous buildings in New York, including many theaters — the stadium contained many visually appealing elements. It was faced with a decorative frieze on the façade of the upper deck, containing a series of allegorical treatments in bas relief, while the façade of the roof was adorned with the coats of arms of all National League teams. “The design at the balcony level is a repeated motif,” explained Herts in an article written for Architecture and Building magazine in 1912, “while that at the roof level contains a series of eight shields repeated in successive panels.” The box seats were designed upon the lines of the royal boxes of the Colosseum in Rome with Roman-style pylons flanking the horseshoe-shaped grandstand on both ends. The aisle seats had figural iron scrollwork with the Giants’ “NY” emblem.

Brush planned to depart from the nomenclature traditionally used for the home of the Giants; the new facility, to reflect his contribution, would be known as Brush Stadium. Fans and news reporters had other ideas, though, and the name Polo Grounds persevered. As Lawrence S. Ritter said of the rebuilt structure in his book, Lost Ballparks, “Polo Grounds it had been and Polo Grounds it would remain.”

Construction in steel, concrete, and marble began on May 10th and by late June, fewer than 11 weeks after the wooden Polo Grounds had burned, the new stadium was ready for baseball. The double-decked grandstand retained the horseshoe configuration of its predecessor although it was built upon much larger lines, rising higher and extending back further, and consisted entirely of steel and reinforced concrete. The only wood used in the entire stadium was for the movable folding opera chairs in the semicircle back of the diamond and in the roof sheathing.

As before, the main entrance was on Eighth Avenue, accessible via the Eighth Avenue Surface Lines. Along the Harlem River Speedway, at the rear of the stadium (behind home plate), was a large auxiliary entrance with ten-foot-wide inclines leading to runways for both the upper and lower decks. “The most convenient automobile or carriage entrance is on the Speedway, opposite 157th Street. When taking the Subway, stop at 157th Street Station, passing north to 158th Street, and then east down the Brush Stairway, built by the New York Base Ball Club, to the new Speedway entrance,” were the instructions provided in Scenes on the Polo Grounds, a commemorative booklet issued by the New York Giants.

Allan Sangree of Baseball Magazine called the rebuilt Polo Grounds “the mightiest temple ever erected to the goddess of sport and the crowning achievement among notable structures devoted to baseball.”

Only 16,000 seats — all in the lower deck — were available for occupancy on Wednesday, June 28, 1911, but it was enough to bring the Giants into their new home on the old lot in Coogan’s Hollow. Christy Mathewson was on the mound for the Giants in first game at Polo Grounds IV and shut out Boston, 3-0. Work continued on the stadium’s superstructure through the rest of the season, and 34,000 fans were able to be accommodated in the 1911 World Series, in which the Giants lost to the Philadelphia Athletics.

Three stadiums before had been known as the Polo Grounds, but the one that opened in 1911 would last twice as long as the other three combined. It would carry the Giants through the golden years of its history and then serve as the home of a new team after the Giants abandoned New York for the West Coast. And, for ten years in its early going, the Polo Grounds served as the home of the New York American League team in addition to the Giants.

The Giants were amenable to letting the Yankees sign a ten-year lease to use the Polo Grounds beginning in 1913. It wasn’t like the Giants felt threatened by their tenants; the Yankees were among the American League doormats and didn’t appear likely to steal the spotlight from the Giants.

That changed at the end of the decade when the Yankees acquired Babe Ruth from the Boston Red Sox. Originally a pitcher, Ruth’s prowess with the bat led to a full-time switch to the outfield, allowing him to be in the lineup every day. With the Red Sox in 1919, Ruth had set a major league record with 29 home runs. The next season, as a member of the Yankees with the Polo Grounds as his home park, Ruth connected for 54 homers and followed that up with 59 in 1921.

The Yankees won the American League pennant for the first time in 1921 and won it again the next two years. Their opponents in each of the World Series were the New York Giants. In 1921 and 1922, all the games in the World Series were played at the Polo Grounds. By 1923, however, the Yankees had a new stadium of their own.

In 1920, Ruth’s first year in New York, the Yankees drew nearly 1.3 million fans to their games at the Polo Grounds and topped the million mark in attendance again in 1921 and 1922. The Giants had never drawn a million fans in one season (and wouldn’t until 1945). John McGraw, who in 1919 had become a part owner in the Giants, was not the type of man to be magnanimous in such a situation. He was the type to be petty and vindictive. McGraw’s jealousy of the Yankees’ success is often cited as a reason for the Giants’ decision to force the Yankees out of the Polo Grounds.

However, there is much more to the story and a number of explanations of what transpired regarding the relations between the Yankees and Giants. Harold Seymour, in Baseball: The Golden Age, says that the American League had been pressuring the Yankees to get their own stadium ever since 1915 when the team was acquired by Colonel Jacob Ruppert and Captain Tillinghast Huston. Another version, also noted in Seymour’s book, has American League president Ban Johnson persuading the Giants to cancel the Yankees’ lease as a means of ousting Ruppert and Huston as team owners.

What is clear is that in mid-May of 1920 (only a month into Ruth’s first season with the Yankees — hardly enough time for jealousy to set in), the Giants informed the Yankees they would have to find a different place to play starting in 1921.

The Giants rescinded their eviction notice a week later, but the Yankees had already begun efforts to find a new place to play. The team settled on a spot just across the Harlem River from the Polo Grounds, at 161st Street and River Avenue in the Bronx. The Yankees continued playing in the Polo Grounds until their new home, Yankee Stadium, was ready for the beginning of the 1923 season.

The end of the 1922 season marked not only the departure of the Yankees from the Polo Grounds but also a radical change in the look of the Polo Grounds. Initially the double-decked stands of Polo Grounds IV had resembled a hook more than a horseshoe. The stands reached approximately 40 feet into fair territory in right field but stopped short of the foul line in left field. Uncovered seats extended out from the permanent stands on both sides and eventually came together in center field.

Plans to renovate and enlarge the Polo Grounds started in 1921 when team president Charles Stoneham met with an architect to explore the possibility of increasing the seating capacity of the Polo Grounds from 38,000 to more than 50,000. In August of 1922 plans were filed with the Manhattan Bureau of Buildings for a massive project that would extend the double-decked grandstand on both the north (left field) and south (right field) sides of the stadium. The grandstands would then curve in toward one another but not actually come together. A uncovered bleacher section — itself divided by a building that housed the clubhouses and administrative offices — was to be wedged between the two grandstand sections in center field with the clubhouse set back from the outfield fences along the bleachers, resulting in an alcove in straightaway center field. The area was in play, even the stairways on each side of the alcove that led to the Giants’ and the visitors’ clubhouses. The massive clubhouse actually served as the center-field fence, although it was so far away that it didn’t really matter.

Work on the stadium renovation began in November of 1922 with the removal of the old clubhouse. Construction proceeded through the winter and continued into the 1923 season. Fans attending the Giants’ home opener in late April saw tall, red columns of steel in right and left field, towers for the pouring of concrete, and thousands of feet of false timber work, which were to become the concrete beds for thousands of new seats.

When construction was finally finished in mid-September of 1923, the Polo Grounds had assumed its final familiar look. “At the left-field foul pole, the concrete wall was 17 feet high, gradually rising to 18 feet in left center and then sloping to 12 feet where the left-field grandstand met the center-field bleachers,” reports Lawrence S. Ritter in Lost Ballparks. “In right field, the wall was 11 feet high at the foul pole, gradually rising to 12 feet where the right-field grandstand met the center-field bleachers. The bleacher seats were behind 4-foot-high concrete walls topped by 4-foot-high wire screen.” So ample was the playing area that it was possible to fit the bullpens into fair territory with nary a chance that they would affect a ball in play. The visitors’ bullpen was in left-center and the home bullpen in right-center, both approximately 440 feet from the plate. In addition, in the center-field alcove, just in front of the clubhouse, was a five-foot high monument containing a tablet dedicated to Eddie Grant, a former Giant who was the first major league player killed in the World War.

Much disappeared in the renovation, including the decorative fresco friezes on the façade of the upper deck. Before the 1920s were out, the coats of arms of the National League teams had also been removed from the top of the grandstand. One feature that did appear as a result of extension of the grandstands was the overhang in left field. Until 1923, the double-decked grandstand on the left-field side had ended before it reached fair territory. With the extension, though, the upper deck extended over the playing field 21 feet beyond the lower deck. (In right field, where the grandstand had already reached into fair territory before it was extended even farther, the upper and lower decks were flush. A photographers’ perch that was later built on the front of the upper deck created a slight overhang — but nothing that approached the extreme of the overhang in left field.)

While the look of the Polo Grounds received its last radical change with the 1922-23 expansion, most aspects of the baseball experience beneath Coogan’s Bluff remained constant, including the setting.

Behind the stadium rose the first portion of Coogan’s Bluff, leveling out briefly for the Harlem River Speedway. A road that still exists (although it is now Harlem River Drive), the Speedway has an interesting history of its own. When it opened in 1898 (with 155th Street as the southern terminus), it was used primarily by harness enthusiasts for trotting-horse trials. It was made a parkway in 1915 and eventually extended southward to hook up with the East River (now Franklin D. Roosevelt) Drive. Although many fans entered the Polo Grounds on the Eighth Avenue side, others came to the stadium along the Speedway. For them, ramps sloped down to a series of small buildings where tickets could be purchased. A different set of ramps took patrons down even farther to the upper and lower seating levels.

From the Speedway, the rocky crag continued upward to Edgecombe Avenue, where the land again leveled out to the west. On this high ground, between Edgecombe Avenue and Jumel Place, was the Jumel Mansion (now the Morris-Jumel Mansion), a 1765 structure that served as British and American army headquarters during the Revolutionary War. Converted in 1903 into a period museum (a function it still holds), the mansion offers a commanding view of the area, which included the Polo Grounds and a portion of its playing field. While the Washington Headquarters Association, operators of the museum, discouraged fans from loitering on the grounds to watch a game, there were many other vantage points in this general vicinity, along the top of Coogan’s Bluff, that offered glimpses of the action.

The look of the Polo Grounds continued to change in its final 40 years, not as dramatically as in the 1920s when the grandstands were extended but in ways that were noticeable.

By the mid-1940s, a pair of batter’s eyes — backdrops to help batters see the pitches more clearly — had been erected atop the bleacher walls on either side of the alcove in center field. Each measuring 20 feet wide and 17 feet high, “they guarded each side of the runway leading to the clubhouse like the impassive lions in front of the main building of the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue,” according to Lawrence S. Ritter in Lost Ballparks.

Advertisements on the outfield walls disappeared before the 1948 season. Gone were the colorful signs for products like Coca-Cola, Gem Razors, Burma-Shave, and Botany Ties. The reason was that the Chesterfield cigarette company, which had erected a large ad on the massive clubhouse wall in center field, didn’t want the competition from other advertisers, even those with non-competing products. In paying $250,000 for the broadcast rights to Giants games on radio and television in 1948, Chesterfield demanded that all other advertising on outfield walls be taken down.

In the 1960s, the clubhouse wall in center was finally used for a scoreboard, but until that time, hand-operated scoreboards were squeezed on to the facing of the upper deck near the foul poles in left and right field.

Inside the stadium, changes in policy were made in the late 1940s to help the players get to the clubhouse after games without having to interact with the fans on the field. It was the end of a quaint tradition and one that usually posed no problems for either the players or the fans. However, following a Dodger-Giant game in April 1949, a Brooklyn fan claimed that he was punched and kicked by New York manager Leo Durocher. Commissioner A. B. “Happy” Chandler finally cleared Durocher of the charges, but the Giants management took action to prevent such encounters in the future. Fans could still exit by their usual route, but they would have to wait until the players and umpires had reached their dressing rooms before going onto the field.

Allowing fans to amble across the field didn’t make any easier the task of maintaining the field, not that these were easy grounds to maintain in the first place. Work had to be done on the Polo Grounds field every fall and winter to offset the natural falling away due to the quicksand which underlay it. The tendency of the Polo Grounds to sink was increased by the subway line that ran beneath the adjacent parking lot. In the mid-1940s, the Giants spent more than $125,000 to raise the field — using approximately 3,000 cubic yards of gravel, 1,500 cubic yards of top soil, and 160,000 square feet of sod — and improve the drainage. This helped with some of the problems, but the job was still a challenging one for the groundskeeper.

Fortunately, by this time the Giants had one of the best, Matty Schwab. Schwab was always close at hand to take care of any problem — very close, since his home was beneath the left field stands. For seven years, Schwab had been the superintendent for Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, responsible for the entire facility, not just the playing area even though the latter was all he was really interested in. A third-generation groundskeeper (Schwab’s grandfather and father had both tended ballparks in Cincinnati), Schwab was amenable to Horace Stoneham‘s offer to come to the Giants in 1946 and be in charge of nothing more than the field.

His first year with the Giants, Schwab and his family — wife Rose and son Jerry — moved into the Concourse Plaza Hotel near Yankee Stadium in the Bronx, but the living arrangements were far from ideal. Schwab tinkered with the idea of moving back to Brooklyn but hated the thought of the long commute to and from the Polo Grounds. Instead, Schwab talked Stoneham into converting some empty space under the left-field stands into an apartment.

A roll-up door on the left-field fence, just to the left of the foul pole, led under the stands to where the entrance of the apartment, which consisted of a kitchen, bathroom, living room, and a bedroom that was used by Jerry. The apartment had windows but none that offered much of a view. All that could be seen was the concourse area between the apartment and the area outside the ballpark to the north (which consisted of the repair area for the subway and elevated cars and then high-rise housing). It was possible for the family to exit the stadium through another roll-up door on the outside stadium wall, although normally they went via car, driving through the concourse under the stands in back of home plate and continuing around the entire stadium until they emerged through a door on Eighth Avenue underneath the grandstand in right-center field. Being on site at all times was handy for Schwab, who — helped by his son — often got up every few hours at night to move the large sprinklers around the field.

For many of the seasons between 1935 and 1950, the Polo Grounds served as a home to another baseball team besides the Giants — the New York Cubans of the Negro National League (Negro American League after 1948).

The Final Years

Two of the most historic events in the history of baseball took place at the Polo Grounds in the 1950s. In 1951, the Giants completed a great comeback in the race for the National League pennant with a three-game playoff series against the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Giants had trailed the first-place Dodgers by 13½ games on August 11, but the Giants won 37 of 44 of their remaining scheduled games, and a playoff was needed to determine the league champion.

The teams split the first two games, and the decisive third game was at the Polo Grounds. The Dodgers carried a 4-1 lead into the bottom of the ninth, but the Giants rallied and had one run in with runners at second and third with one out. Ralph Branca was brought in to relieve Brooklyn starter Don Newcombe. His first pitch to Bobby Thomson was a strike. Thomson turned on the next pitch and lifted a fly toward left. In many, if not all, of the other stadiums in the major leagues, it likely would have been nothing more than a fly out. But this was the Polo Grounds.

As Brooklyn left fielder Andy Pafko stood at the fence, the 315-foot marker near his feet, he stared up helplessly as the fly settled into the lower grandstand, a three-run homer to give the Giants the game, 5-4, and the National League championship.

In the broadcast booths, while Ernie Harwell described the play for television viewers, on the radio side Russ Hodges was shouting into the microphone his rendition that would become a classic in the annals of sports announcing: “The Giants win the pennant . … The Giants win the pennant …”

Although the Giants couldn’t carry the momentum into the World Series — they lost, four games to two, to the Yankees — Thomson’s “Shot Heard ‘Round the World” remains one of the most famous ever hit and has often been cited as the most memorable moment in baseball history.

Baseball historian John McCormack — who attended many games, at the Polo Grounds between 1924 and 1953, including the 1951 playoff finale — disputes the claims that Thomson’s drive was nothing more than a “Polo Grounds home run.” After a writer said Thomson’s homer “looped into the shorter lower left field stands,” McCormack responded, “Neither Bobby Thomson nor anyone else ‘looped’ a homer into the lower left field stands at the Polo Grounds. Thomson hit a line drive, the only type drive that could get into those stands. There were a lot of cheap home runs hit at the Polo Grounds. But none went into the lower left field stands. Why? Because of the Polo Grounds’ curious configuration. The upper left field stands jutted out over the lower stands perhaps 15 to 20 feet. As a result, any looping drive that didn’t get into the upper stands would hit the façade for a home run or be caught by the left fielder. There was no way it could fall into the lower left field stands. … Thomson’s drive would have been a home run at Ebbets Field or most of the National League parks of the time. It was no cheap drive.”

Researcher John Pastier, also a frequent denizen of the Polo Grounds, says the distance on the home run could have been as short as 340 feet (the spot of the field-level landing point had there been no obstructions) and as much as 355 feet, although he says the latter figure is “stretching it.” Had the distance been 350 feet, Pastier claims it would have been an out in most other ballparks.

No matter. Regardless of whether Thomson’s fly ball would have been a home run nowhere but the Polo Grounds, it was the Polo Grounds where it was hit.

But the game above all others that best demonstrates the vagaries of the Polo Grounds — and how the stadium could taketh away as well as giveth — may have been the opener of the 1954 World Series between the Cleveland Indians and New York Giants at the Polo Grounds.

With the game tied in the eighth inning, Cleveland had runners on first and second with no out when Vic Wertz drilled a tremendous drive to center field. Giants centerfielder Willie Mays turned and ran back toward the fence to the right of the alcove. Mays stuck out his glove and, three steps in front of the warning track, caught the fly over his right shoulder. The catch was remarkable, but so was what he did next. Mays was so far away that if he couldn’t get the ball in quickly, Larry Doby would have a chance to tag up and score all the way from second base. Mays spun and heaved the ball back toward the infield as he fell to the ground. Doby was able to get no farther than third on the play and was stranded there by the subsequent Cleveland batters. Thanks to Mays’s great play, the game remained deadlocked.

In the last of the tenth inning, with the score still 2-2, the Giants put runners on first and second with one out. Dusty Rhodes, a lefthanded batter, pinch hit for Monte Irvin and lifted a fly to right field. Right-fielder Dave Pope drifted over toward the line but quickly came up against the fence. He leaped but the ball came down beyond his reach, into the first row of fans for a game-winning home run.

Dusty Rhodes won the game with a home run that traveled barely 280 feet while, two innings earlier, Vic Wertz sent one well in excess of 400 feet that was nothing more than a long fly out. The Giants went on to sweep the Indians, who had set an American League record with 111 wins during the regular season, to win the World Series.

The 1950s turned into a most tumultuous period for fans of the National League baseball teams in New York.

Reports of the possible abandonment of the Polo Grounds had begun in the early 1950s. In the September 1953 Sport magazine, Jack Orr wrote, “There have been recent rumors that the Giants, at the expiration of their current lease in 1962, will turn the tables and become tenants of the Yankees.” That fall, planner Robert Moses — the “master builder” of New York City — suggested that the Giants make the move even sooner than that so the Polo Grounds could be torn down and used for public housing.

Soon the uncertain future of the Polo Grounds was casting shadows on the future of the Giants in New York. The team wasn’t averse to leaving the Polo Grounds. Parking had always been a problem, the stadium was becoming run down, and the neighborhood was also deteriorating. (Before the start of an Independence Day doubleheader in 1950, a fan in the upper grandstand of the Polo Grounds was even killed by a stray bullet fired from outside the stadium.)

Moving into Yankee Stadium was one alternative. A new stadium, built by the city, was one that appealed even more to owner Horace Stoneham (who had taken over the team from his dad, Charles Stoneham). Soon was making it clear that the Giants were no longer limiting their options to New York City. Meanwhile, similar threats were being made in Brooklyn. Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley, also wanting a new stadium, was viewing the fertile territory on the west coast as a possible place to play. In turn, Stoneham looked in the same direction, and that’s where both teams ended up. In 1957, Stoneham and O’Malley announced they were moving the Giants and Dodgers to San Francisco and Los Angeles, respectively.

On Sunday, September 29, 1957, the Giants brought their history in New York to an end before a crowd of 11,606 at the Polo Grounds.

National League baseball had abandoned New York City — but the two ballparks, Ebbets Field in Brooklyn and the Polo Grounds — remained for several years and were used for a variety of events. Ebbets Field was finally knocked down in February of 1960; the Polo Grounds not only lived on but had a rebirth of sorts.

First, it absorbed a soccer team that had been playing at Ebbets Field. It also obtained a new football tenant, the New York Titans (later renamed the Jets) of the American Football League in 1960. And, by 1962, baseball had even returned. Ironically, by this time, the death warrant for the Polo Grounds had been issued and it was clear that the stadium was in its final years.

Baseball — the primary sport associated with the Polo Grounds — came back when New York was granted a National League franchise. The process began in 1959 when the Continental League was formed as a potential third major league. New York was one of the cities designated for a franchise in the Continental League, which ended up disbanding (before ever actually operating) after receiving agreement from the major leagues to absorb some of its teams, including New York.

It meant that, starting in 1962, New York would have a team in the National League again, this one taking the name of its American Association predecessor from the 1880s, the Metropolitans (although this team would be known simply as the Mets).

Part of the bargain, however, was that the Mets would have a new stadium. In January of 1961, the New York City Board of Estimate approved plans to build a stadium in Flushing Meadow (a portion of the borough of Queens). The stadium wouldn’t be ready until at least 1963, which meant the Mets would have to find another place to play in their initial season. The Mets sought permission from the Yankees to share Yankee Stadium with them for a year.

The month of March 1961 was an active one in terms of issues related to the Mets, including a scare that left the future of the team in doubt. On Wednesday, March 15, the New York State Assembly — which had to pass a bill authorizing the city to finance and build the stadium and lease it to the Mets — fell well short of the two-thirds vote needed for approval. Without passage of the bill, there would be no stadium, and without the stadium, there would be no Mets. The setback didn’t last long, though. A number of dissenters were persuaded overnight to change their votes, and the next day the measure necessary for a new stadium to be built was passed by a vote of 119-17.

That crisis out of the way, the long-term plans for the Mets were solidified. Short-term plans, however, remained in limbo as the Yankees made it clear they had no intention of allowing the Mets to share their stadium.

That left the Polo Grounds as the remaining option for the Mets. Although the stadium had continued to be used for other events after the departure of the Giants, baseball hadn’t been played there since 1957, and a great deal of work would have to be done to make it suitable for a baseball tenant again. The Mets were willing to incur the expenses for the necessary renovations, but a larger problem loomed.

On March 9, 1961, the New York City Board of Estimate had doomed the Polo Grounds with a decision to demolish the stadium to allow the New York City Housing Authority to erect a low-rent housing project — consisting of four 30-story towers to house more than 1,600 families — on the site. (The decision wasn’t made with the blessing of the Coogan heirs, who still owned the site. Jay Coogan, who fought the takeover attempt by the city, had earlier appeared before the City Planning Commission with a proposal to convert the stadium into a covered “sports palace,” one with a price tag of $45 million. The commission rejected Coogan’s plan, though, stating that the need for low-income housing was greater. The value of the land was hotly contested by both sides and wasn’t resolved until a decision was issued by the New York Court of Appeals in November 1967, more than three years after the stadium had been razed.)

Since the New York Titans of the American Football League already had a lease to use the Polo Grounds through the end of 1961, it meant that the city couldn’t proceed with its plans for a housing project on the site until 1962 at the earliest. Understanding the plight of the New York Mets in needing a temporary home, the city further delayed the housing project for at least another year.

This was good news for New York baseball fans, particularly those who had learned to loathe the Yankees and had been hungry for another National League team to cheer for. (Some Brooklyn fans, though, still associated the Polo Grounds with the once-hated Giants and made it known they would not attend a Mets game until the team’s new stadium, in the neutral territory of Queens, was ready.)

The Mets proceeded with work to get the Polo Grounds ready for baseball and spent more than $300,000 on the project, a huge sum considering that they were planning on using the stadium only for a year. The refurbishing included painting of the fences and stands, replacement of lamps and reflectors in the lighting towers, installation of an electronic scoreboard that stretched across the clubhouse in center field, and construction of a private cocktail club and restaurant known as the Met Lounge. Advertising signs once again adorned the outfield fences.

The biggest project, though, dealt with the playing area itself. (Some of the events held in the Polo Grounds after the departure of the Giants were tough on the turf. One such event was midget auto racing, which was run on an asphalt track that had been constructed on the field.) The grounds crew plowed the entire field, brought in topsoil, and spent a month grading the area before placing more than 130,000 square feet of sod.

The face lift of the Polo Grounds was a massive effort but one that was well worth it. New Yorkers were exciting about their new team, and, for their initial season, the Mets rang up the largest sale ever for season tickets at the Polo Grounds.

The Polo Grounds’ previous tenant, the Giants, had been one of the most storied teams in baseball history. The Mets established their identity at the Polo Grounds in an entirely different way. In its own perverse manner, though, the ineptness and futility of the Mets proved as big a hit with the fans as the legacy of greatness that had characterized the Giants. The Mets finished the season with 120 losses — most in the majors since 1899 — out of 160 games, a losing percentage of .750.

As highlights and lowlights punctuated the 1962 season, construction on the stadium in Flushing Meadows was underway. Hampered by labor disputes and problems with subcontractors, the project was behind schedule in August 1962 and slowed further by harsh weather over the winter of 1962-63.

Still, when the Mets concluded their regular season in 1962, they fully expected to be in their new home for the opening of the next season. In fact, the New York Times headline of Monday, September 24, 1962 read “Mets Beat Cubs, 2-1, in Farewell to Baseball at the Polo Grounds.” A crowd of 10,304 attended what they thought would be the stadium’s final baseball game.

However, the Polo Grounds received still another reprieve. When it became clear the Flushing Stadium wouldn’t be ready, the Mets resigned themselves to at least another partial season beneath Coogan’s Bluff. It turned out to be a full season at the Polo Grounds with the final game played before only 1,752 fans — the smallest crowd to see the Mets at the Polo Grounds. “Maybe the fact that there had been two previous ‘last games’ [the 1957 Giants finale and final home game in 1962] at the Polo Grounds took a bit from the occasion,” wrote Gordon S. White, Jr. in the New York Times. “It is hoped that no more Mets games will be played at the Polo Grounds — if only to put an end to the string of finales.”

This was the final finale, with the Philadelphia Phillies beating the Mets, 5-1. The end came at 4:21 p.m. on Wednesday, September 18, 1963 with New York’s Ted Schreiber hitting into a double play to end the game. Jim Hickman provided the Mets’ only run in the fourth inning with a home run, the last ever hit at the Polo Grounds.

The Polo Grounds hosted one more baseball game, a Latin All-Star Game on October 12, 1963, with the National League beating the American League 5-2.

In January of 1964, the Mets moved their offices out of the Polo Grounds and into the new stadium in Queens, which became known as Shea Stadium. That April, demolition of the Polo Grounds started with the same wrecking ball that had been used four years earlier on Ebbets Field. The wrecking crew wore Giants jerseys and tipped their hard hats to the venerable stadium as they began the dismantling. It took a crew of 60 workers more than four months to bring the venerable structure down.

Other Sports and Events

The final baseball game wasn’t the final event at the Polo Grounds. The official end to the stadium came with an American Football League game between the Buffalo Bills and New York Jets (formerly the Titans) on Saturday, December 14, 1963. Buffalo quarterback Jack Kemp, who entered the game in place of starting quarterback Daryle Lamonica, led a second-half surge that gave Buffalo a 19-10 win over the Jets before a dismal crowd of 5,826.

The New York Giants football team had also used the Polo Grounds from 1925 to 1955 before moving to Yankee Stadium. For many years, college football was more prominent than the professional game. Area colleges, as well as some schools from far away, scheduled games at the Polo Grounds, and, for a time, the park served as the home for Dartmouth College of Hanover, New Hampshire. Beginning in 1913, the Polo Grounds also became the regular site of the annual Army-Navy game.