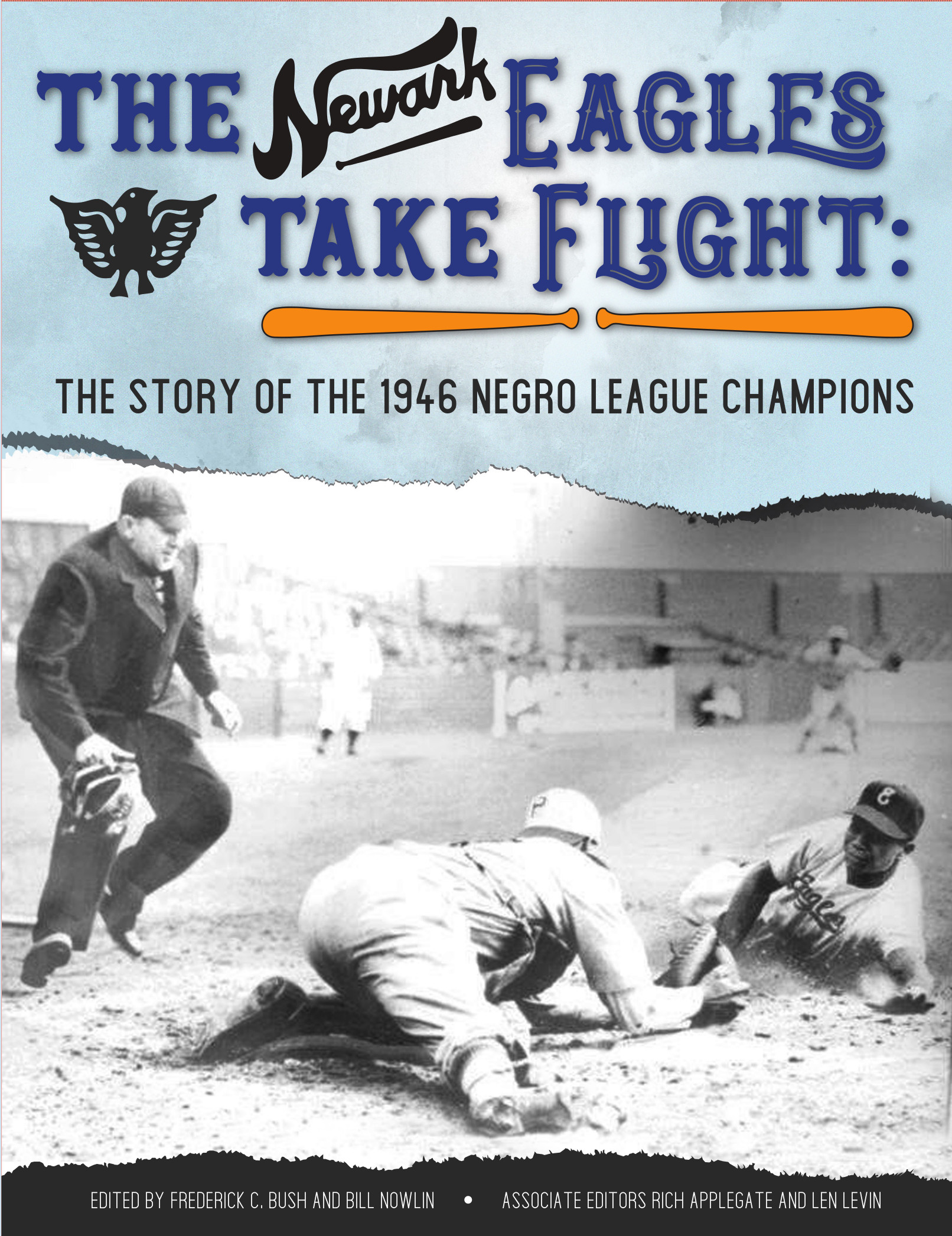

Biz Mackey and Japan

This article appears in SABR’s “The Newark Eagles Take Flight: The Story of the 1946 Negro League Champions” (2019), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

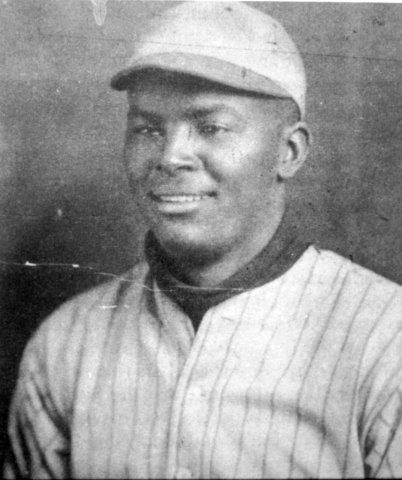

Throughout his career, Biz Mackey served as an international baseball goodwill ambassador by competing in Cuba, and crossing the Pacific to play exhibition games in Hawaii, Japan, Korea, China, and the Philippines.

Throughout his career, Biz Mackey served as an international baseball goodwill ambassador by competing in Cuba, and crossing the Pacific to play exhibition games in Hawaii, Japan, Korea, China, and the Philippines.

According to Japanese baseball historian Kazuo Sayama, Mackey’s tours to Japan as a member of the Philadelphia Royal Giants in 1927 and 1932-33 played an important role in the development of professional baseball in Japan in 1936.1 To better appreciate Sayama’s position, it’s important to understand the factors at play during the game’s early evolution in Japan.

Baseball was introduced to Japan in the 1870s and by the 1920s it rivaled sumo wrestling as the nation’s favorite sport.2 However, despite their passion for the game, at that time the skill level of Japanese ballplayers did not equal that of the Americans.

Prior to the Royal Giants’ initial tour, major leaguers made four visits to Japan – in 1908, 1911, 1920, and 1922. The first three tours were positive and helped establish a stronger baseball bond between the United States and Japan. But all of that goodwill was damaged in 1922 when Herb Hunter‘s All-Stars disrespected their hosts by intentionally losing a game. “We welcomed the American team because we thought they were gentlemanly and sportsmanlike,” one Japanese participant told the Tokio Asahi, “but they disappointed our hopes and left an unpleasant impression upon us.”3 Major leaguers did not return to Japan for another nine years.

Among the teams filling this major-league void in Japan were the Philadelphia Royal Giants in 1927. Mackey and notable teammates Andy Cooper, Rap Dixon, and Frank Duncan first won the hearts of Japanese fans and the respect of opposing players by displaying impressive talent and true sportsmanship.

Mackey in particular left a lasting impression. He hit the first home run ever recorded at Meiji Shrine Stadium, and he even made headlines after getting hit by a pitch. The opposing pitcher bowed to Mackey to apologize for hitting him, and in a display of mutual respect, Mackey bowed back.4

Led by team captain Mackey, the Royal Giants returned to Japan in late 1932. Some Japanese players who competed against the Royal Giants told Sayama in Gentle Black Giants that the Negro Leaguers’ return visit couldn’t have come at a better time.

White major leaguers players resumed tours of Japan in 1931, billing themselves as the Herb Hunter & Fred Lieb All-Stars. They won all 23 of their games, many of which were blowouts and/or shutouts. Opposing Japanese players observed that the Americans approached these games with arrogance, and an attitude that said, “We are experts, let us teach you how to play.”5

Among the All-Stars was Lou Gehrig, who was on year six of a 14-year run toward his consecutive-games-played streak of 2,130. During the 1931 tour, Gehrig was involved in an incident that was a mirror opposite of Mackey’s graceful bow. A Japanese pitcher accidentally hit Gehrig on the wrist with an inside pitch. With his streak top of mind, Gehrig removed himself from the game and, to avoid further injury, refused to play for the remainder of the tour.6

Among the All-Stars was Lou Gehrig, who was on year six of a 14-year run toward his consecutive-games-played streak of 2,130. During the 1931 tour, Gehrig was involved in an incident that was a mirror opposite of Mackey’s graceful bow. A Japanese pitcher accidentally hit Gehrig on the wrist with an inside pitch. With his streak top of mind, Gehrig removed himself from the game and, to avoid further injury, refused to play for the remainder of the tour.6

Unlike the major leaguers of 1931, the Royal Giants approached the games and their opponents with an attitude of “we are friends, let’s play ball together.” In doing so, Mackey and his teammates created a comfortable, safe, and fun environment for the Japanese players to improve their skills while playing against high-caliber competition. It was for this approach that Mackey and his teammates earned the term of endearment “gentle, black giants.”7

“We (Japan) yearned for better skill in the game. But if we had seen only the major leaguers, we might have been discouraged and disillusioned by our poor showing,” wrote Sayama. “What saved us was the tours of the Philadelphia Royal Giants, whose visits gave Japanese players confidence and hope.”8

The Royal Giants made a final visit to Japan in late 1933 – this time without Mackey, who most likely remained in the States due to a commitment to his new team the Philadelphia Stars, or declined because of a nagging arm injury, or both.9 For the players who did make the trip, rainy weather prevented them from competing on the field in Japan. Instead, the team dined and enjoyed time with their Japanese hosts before moving on to the Philippines.10

Major leaguers returned to Japan in November 1934. Babe Ruth impressed observers with his powerful home runs, but as in the previous tours the All-Americans disrespected the Japanese players on the diamond. Former player Yasuo Shimazu shared his memories:

In a game held in the rain at Kokura in 1934, Babe Ruth took to the field as a first baseman with a Japanese umbrella over his head, and Lou Gehrig, who was playing as a left fielder, had rubber rain shoes on. In another game, when Lefty Grove was pitching, left fielder Al Simmons laid himself on the field to show he had nothing to do but lie down and watch what Lefty was doing. They may have been intended their actions to be a show, but many Japanese fans weren’t altogether happy.11

Two years after Ruth’s visit, the first professional Japanese baseball league was founded. According to Sayama, professional baseball was able to materialize in Japan because the Japanese players had what he called “a good shock absorber.” Some countries rejected baseball because the visiting professionals left fledgling players disillusioned with the game through defeat. “We were lucky enough to have the chance to neutralize the shock. The Royal Giants’ visits were the shock absorber.”12

In his 1987 article, “Their Throws Were Like Arrows: How a Black Team Spurred Pro Ball in Japan,” Sayama concluded:

Baseball has in it many elements that appeal to the Japanese mind, and it may safely be said that professional baseball would have been born in the course of time. Without the visits of the gentlemanly and accessible Royal Giants, however, I don’t think it would have seen the light of day as early as 1936.13

The positive influence of Biz Mackey and the Royal Giants did not end in 1936. Future Japanese Baseball Hall of Famer Shinji Hamazaki competed against the Royal Giants as a member of the Mita Club, the Keio University alumni team, and his interactions with Negro League players left a positive impression on him.14 Years later he was named manager of the Hankyu Braves, and when foreign players were permitted to play in Japan in the early 1950s, Hamazaki recruited four black players from America: John Britton, third baseman; Jimmie Newberry, pitcher; Larry Raines, shortstop; and Jonas Gaines, pitcher.15

In 1962 two of Mackey’s former players with the Newark Eagles, Larry Doby and Don Newcombe, followed their manager’s footsteps and journeyed across the Pacific to play the final season of their careers in Japan.16

BILL STAPLES JR. has a passion for researching and telling the untold stories of the “international pastime.” His areas of expertise include Japanese American and Negro Leagues baseball history as a context for exploring the themes of civil rights, cross-cultural relations, and globalization. He is a board member of the Nisei Baseball Research Project, member of the Japanese American Citizens League, and chairman of the SABR Asian Baseball Committee. He is the author of Kenichi Zenimura, Japanese American Baseball Pioneer (McFarland, 2011), winner of the 2012 SABR Baseball Research Award, and coauthor of Gentle Black Giants: A History of Negro Leaguers in Japan (NBRP Press, 2019). Bill lives in Chandler, Arizona, with his wife and two children and is an active community volunteer and youth coach.

Notes

1 Kazuo Sayama, “Their Throws Were Like Arrows–How a Black Team Spurred Pro Ball in Japan,” Baseball Research Journal 16 (1987): 85–88.

2 newspapers.com/clip/27693002/baseball_national_sport_of_japan_1928/ or N.K. Roscoe, “The Development of Sport in Japan,” Japan Society of London, Transactions and Proceedings 30 (1932–33).

3 “Big Leaguers Boot One in Japan, Herbert Hunter Takes Major League All-Stars to Japan,” Fresno Bee, December 14, 1922: 9. 43.

4 Sayama, “ ‘Their Throws Were Like Arrows.’’’

5 Kazuo Sayama and Bill Staples Jr., Gentle Black Giants: A History of Negro Leaguers in Japan (NBRP Press, 2019).

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Sayama, “ ‘Their Throws Were Like Arrows.’’’

9 Bob Luke, “Biz Mackey: Catcher, Manager, Mentor Extraordinaire,” Black Ball: A Negro Leagues Journal, Vol. 1, No. 2, (Fall 2008).

10 Sayama and Staples.

11 Sayama, “ ‘Their Throws Were Like Arrows.’’’

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 To learn more about Shinji Hamazaki and other members of the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame, visit: http://english.baseball-museum.or.jp.

15 “The Secret History Of Black Baseball Players In Japan,” npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2015/07/14/412880758/the-secret-history-of-black-baseball-players-in-japan.

16 Associated Press, “Doby to Play Jap Baseball,” Baltimore Sun, June 24, 1962: 104. newspapers.com/clip/27693321/doby_newcombe_in_japan_1962/.