Go-Going-Gone: Bill Veeck’s Trades and Their Consequences

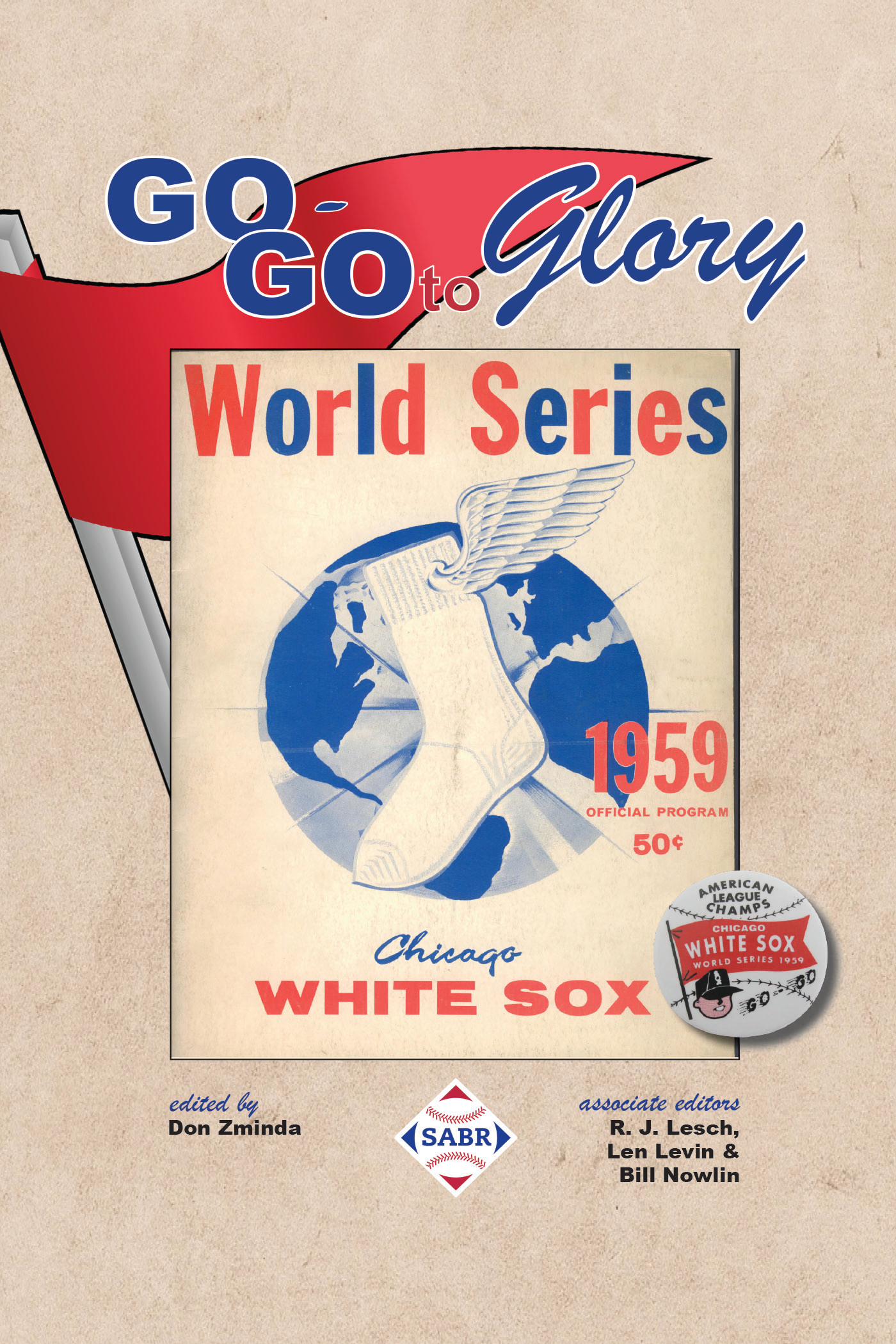

This article appears in SABR’s “Go-Go to Glory: The 1959 Chicago White Sox” (2019), edited by Don Zminda.

No book about the 1959 White Sox would be complete without a discussion of what happened after the season – in particular, four trades engineered by team president Bill Veeck and general manager Hank Greenberg in an effort to repeat as American League champions in 1960. Each deal featured the same theme: trading young but mostly unproven talent for experienced veterans who were more likely to have an immediate impact. Here are the details of the four trades, along with the ages of the players on Opening Day 1960 (for Minnie Minoso, I am using his current listed date of birth, which is three years younger than his listed DOB during his playing days):

No book about the 1959 White Sox would be complete without a discussion of what happened after the season – in particular, four trades engineered by team president Bill Veeck and general manager Hank Greenberg in an effort to repeat as American League champions in 1960. Each deal featured the same theme: trading young but mostly unproven talent for experienced veterans who were more likely to have an immediate impact. Here are the details of the four trades, along with the ages of the players on Opening Day 1960 (for Minnie Minoso, I am using his current listed date of birth, which is three years younger than his listed DOB during his playing days):

Bill Veeck’s 1959-60 Trades

(Player ages as of Opening Day 1960)

- December 6, 1959: White Sox trade catcher John Romano (25), third baseman Bubba Phillips (32), and first baseman Norm Cash (25) to the Indians for outfielder Minnie Minoso (34), catcher Dick Brown (25), and pitchers Don Ferrarese (30) and Jake Striker (26).

- December 9, 1959: White Sox trade outfielder Johnny Callison (21) to the Phillies for third baseman Gene Freese (26).

- April 4, 1960: White Sox trade catcher Earl Battey (25), first baseman Don Mincher (21), and $150,000 to the Senators for first baseman Roy Sievers (33).

- April 18, 1960: White Sox trade pitcher Barry Latman (23) to the Indians for pitcher Herb Score (26).

In an article about the four trades in his book Rob Neyer’s Big Book of Baseball Blunders, the author pulls no punches: “All four trades were absolute disasters,” wrote Neyer. Hardly any veteran White Sox fan would disagree. A summary of the aftermath of the four trades:

- Brown, Ferrarese and Striker hardly played for the White Sox, but Minnie Minoso gave the White Sox two good years in his return to the team and the town that loved him (.311-20-105 in 1960; .280-14-82 in 1961). As for the men the Sox dealt away, Norm Cash hit 373 home runs after leaving the White Sox (all for the Tigers, who acquired him from Cleveland prior to the start of the 1960 season), with a batting title and four appearances on the AL All-Star team; John Romano became a two-time All-Star catcher for the Indians; and even Bubba Phillips had a couple of serviceable years for the Tribe.

- Roy Sievers gave the White Sox two almost identically good seasons (.295-28-93 in 1960; .295-27-92 in 1961). However, Earl Battey became a four-time All-Star and three-time Gold Glove winner for the Senators/Twins; Don Mincher hit 200 home runs, made two All-Star teams and played on two American League pennant-winners (the 1965 Twins and the 1972 Athletics).

- Gene Freese had one 17-home-run season for the White Sox before being dealt away. The man he was traded for, Johnny Callison, became a three-time All-Star for the Phillies, was runner-up in the 1964 National League MVP voting and hit 222 home runs after leaving the White Sox.

- Herb Score went 6-12 in three seasons with the White Sox; Barry Latman won 47 games after the trade (though with 61 losses) and – of course! – made an All-Star team, in 1961.

- The bottom line: the White Sox didn’t come close to a pennant in the first few years after the trades, finishing third in 1960, fourth in 1961, and fifth in 1962.

Ouch! As Bob Vanderberg wrote in his 1982 book Sox: From Lane and Fain to Zisk and Fisk, “Many South Side fans have yet to forgive Veeck for mortgaging their future.”

In fairness to Bill Veeck, this is looking at the trades from years of hindsight, and in the spring of 1960, a lot of people thought the White Sox had just wrapped up another pennant. Writing in the season-opening issue of The Sporting News in April of 1960, Chicago sportswriter Jerry Holtzman (he didn’t become known as Jerome until several years later) predicted “a pennant again, possibly breezing.” And in the annual poll of baseball writers in the same edition of The Sporting News, the Sox were the consensus choice to win the American League pennant, gathering nearly twice as many first-place votes (120) as the Indians (70), who finished second in the balloting.

Even then, though, many people in Chicago were nervous about the trades. When the trades for Minoso and Freese were announced, Holtzman wrote, “The criticism lashed at Veeck and Vice Presidents Chuck Comiskey and Hank Greenberg (who were with him at the winter meetings where both trades were consummated) was that the deals simply were designed for short-term results. There just wasn’t enough thought given to the future, the next two or three years, when surely the Sox will need front-line replacements.” Prophetic words there.

The reaction to the trade for Sievers the following April was a lot more positive, with Holtzman writing, “The trade was a master stroke for the Sox. … the Hitless Wonders tag is a thing of the past.” However, Holtzman wrote in the same article that the deal had taken a little time to consummate because the Senators wanted light-hitting utilityman Sammy Esposito, who had batted .167 for the ’59 pennant winners, as part of the deal instead of Mincher. According to Holtzman, “[Manager Al] Lopez refused. He said he would part with Battey, but that he wouldn’t part with Esposito.” So to review Veeck and Lopez’s winter and spring, their stance toward the club’s young talent was:

- Sure, Callison’s a hot prospect, but that Freese is so Tastee!

- Norman Cash? Gone in a dash

- Catchers, who needs catchers? Battey and Romano, away they go!

- Don Mincha, we’ll never miss ya

- Barry Latman, Larry Batman, whatever your name is – you’re history

- But Sammy Esposito … that’s where we draw the line!

No wonder the South Side had trouble forgiving Veeck.

So can anyone defend old Will? It’s difficult, but let’s try to mount at least a semblance of justification for these deals:

- Minoso, Freese, and Sievers did help improve the Sox offense in 1960, and not just a little. The club, which had scored 669 runs and hit 97 home runs in 1959, scored 741 runs with 112 homers in 1960. The failure to repeat was much more the fault of the pitching staff, as the team ERA rose from 3.29 to 3.60 and no Sox pitcher won more than 14 games.

- Veeck may have felt that the Sox had a lot of good fortune in winning the 1959 pennant, and that they were unlikely to repeat without strengthening the roster. That was not an unreasonable position; the Sox outscored their opponents by only 81 runs in 1959, and the pennant was due in good part to their extraordinary success in one-run games (35-15, .700). In 1960 the trades helped the Sox outscore their opponents by 124 runs, but the magic in one-run contests was gone – the club went 22-23 in minimum-margin games.

- In the spring of 1960, hardly anyone would have predicted stardom for Norm Cash, who was 25 years and had played very little above the low minors. In fact, the Indians quickly unloaded Cash after acquiring him, trading him to the Tigers for a nobody (Steve Demeter).

- Earl Battey had been up with the Sox in for at least part of every season from 1955 through 1959, and hadn’t shown much hitting prowess (.209 average in 358 at-bats, though with 13 home runs). He was widely regarded in Chicago as a good defensive catcher but a poor hitter.

- Don Mincher had shown power potential in the low minors, but he had yet to play above the Class A Sally League.

- Callison, widely considered the star of the group, had lost a bit of his luster by hitting .173 in 104 at-bats for the Sox in ’59.

Finally, the Sox did receive some more payback out of Freese, Sievers, and Minoso when they dealt them away in three trades that all look pretty astute in retrospect (the first trade was made by Veeck, the latter two by new general manager Ed Short after Veeck sold the team to Arthur Allyn in June of 1961):

White Sox Trades 1961-62

(Players’ ages as of Opening Day 1961 or 1962)

- December 15, 1960: White Sox trade third baseman Gene Freese (27) to the Reds for pitchers Juan Pizarro (24) and Cal McLish (35).

- November 18, 1961: White Sox trade first baseman Roy Sievers (35) to the Phillies for pitcher John Buzhardt (25) and third baseman Charley Smith (24).

- November 27, 1961: White Sox trade outfielder Minnie Minoso (36) to the Cardinals for first baseman Joe Cunningham (30).

Gene Freese, the much despise-ed, went to Cincinnati in a deal that brought the Sox left-hander Juan Pizarro, who went 61-38 with a 2.93 ERA from 1961-64 and was a key element in the rebuilding of the club’s pitching staff. Similarly, Roy Sievers went to the Phillies in a trade that netted righty John Buzhardt, who was 40-32 with a fine 3.17 ERA from 1962-65. And the Sox traded Minoso, who was reaching the end of the line, to the Cardinals for Joe Cunningham, who had an excellent season for the South Siders in 1962 (.410 OBP) and was having another good year in 1963 (.388 OBP) until he fractured a collarbone. Then in 1964, the Sox dealt Cunningham to the Senators in a trade which netted them useful veteran (and Chicago native) Bill Skowron, a South Side favorite who is still working for the White Sox more than 40 years later.

Even with the caveat that Veeck was gone by the time the Sox dealt away Sievers and Minoso, those three trades make the White Sox look a little better.

But not good enough. Two questions still nag at me:

- Why did they get so little for Callison when he was universally regarded as one of the top prospects in baseball? With all due respect for Gene Freese, this looked like a lopsided trade in favor of the Phillies even at the time it was made.

- Why trade away two power-hitting first-base prospects and two good young catchers when the Sox regulars at both positions (Ted Kluszewski and Sherm Lollar) had passed their 35th birthdays?

Like a lot of Sox fans, I still can’t get over it.

DON ZMINDA has been a White Sox fan since attending his first game at Old Comiskey in August of 1954. As Director of Publications for STATS, Inc. (now STATS LLC) from 1988-2000, he co-authored or edited a dozen annual sports publications. Don’s book “The Legendary Harry Caray: Baseball’s Greatest Salesman” was published by Rowman & Littlefield in April 2019. A SABR member since 1979, he is retired and had lived in Los Angeles with his wife Sharon since 2000.